Michael Bloomfield From His Head to his Heart to his Hands: An Audio/Visual Scrapbook (Columbia Legacy)

Finally, this extraordinary Chicago-born guitarist is no longer playing the blues in history’s alleyway. Al Kooper — who met Bloomfield when both played on Bob Dylan’s epochal “Like a Rolling Stone” — curates this “” with love and diligence. 1

The four-disc set includes a new DVD documentary film Sweet Blues: A Film about Mike Bloomfield that tells the moving human story of a hot-wired musical genius, with a photographic memory. Hear Bloomfield trip the lights on for the psychedelic era and much of his era that grew from the blues. He seemed ill-suited for stardom by temperament and trait — a scholarly type afflicted with chronic, perhaps bi-polar insomnia, and a pedestrian Joe Blow singing voice.

But what a guitarist! A relentless woodshedder, Bloomfield encompassed myriad moods, and played more blues styles than virtually anyone. His guitar’s searing intensity beamed a pearly, sweet tone that kissed the listener’s ear while electrifying it. He filtered B.B. King through his own voracious sensibility and mensch-like Jewish exuberance. He broke barriers with a prototype racially integrated music group — the brash, churning Paul Butterfield Blues Band — which set rock musicians on their ears.

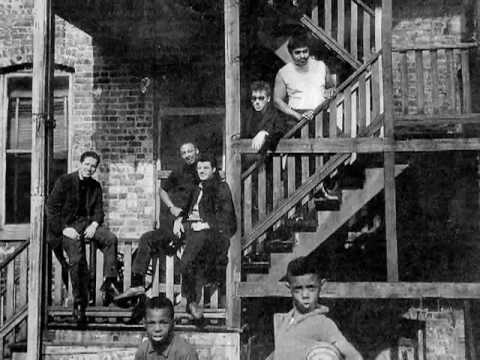

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, on Chicago’s South side, around the time of their eponymous debut album (l-r) Paul Butterfield, Jerome Arnold, Michael Bloomfield, Elvin Bishop, Sam Lay. Courtesy article.wn.com.

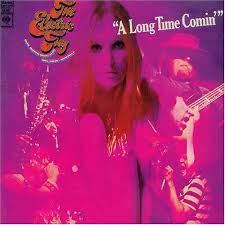

You hear the 1966 title tune from their second album, East-West, a magnificently precipitous bridge spanning blues, jazz and Eastern raga. Bloomfield soon formed The Electric Flag, a forerunner of many blues-R&B-jazz horn groups, including the Tedeschi Trucks Band. Bloomfield’s electric picking peaks on the midnight jam Super Session and subsequent live performances; then his band launches Janis Joplin’s solo career. “One Good Man” from Joplin’s first solo album I’ve Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama! yearns with the lonesome blues expression both these artists understood deeply. Wherever he went, Bloomfield exuded ideas and passion as unquenchable fire. He followed his talent, vision, historical acuity and his generosity. He did what he wanted to do, but not as a careerist.

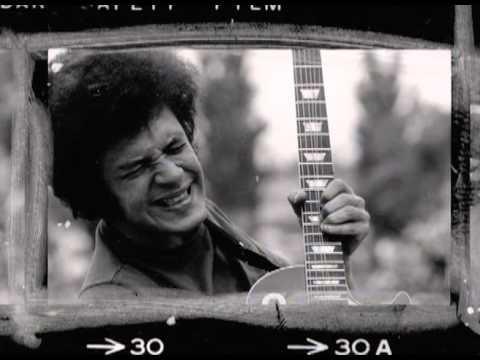

Mike Bloomfield “is the guitar,” says Country Joe McDonald. Courtesy examiner.com.

The set’s previously unreleased bookends are his startling 1964 rehearsals for the historic producer John Hammond — and his 1980 live gig with Dylan, three months before he died at age 37. In the 1964 sessions he astounds Hammond (who had discovered Billie Holiday, Benny Goodman, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, Bruce Springsteen and other greats) who, after Michael’s impromptu “Hammond’s Rag” the producer tells him through the studio intercom, “We’ve exploited you enough; I just want you to know I’m signing you.” “Oh!” Bloomfield cries.

But first, he had to play the blues and beyond, with Butterfield for several crucial years. 2 Bloomfield composed the band’s brilliantly conceived and executed 13-minute instrumental “East-West,” which revealed a superb ensemble attunement to a long-form exploratory context. The piece opened up many musicians of Bloomfield’s generation to the possibilities of jazz and world music, yet few extended works from that generation equal East-West in power, imagination or cohesion.

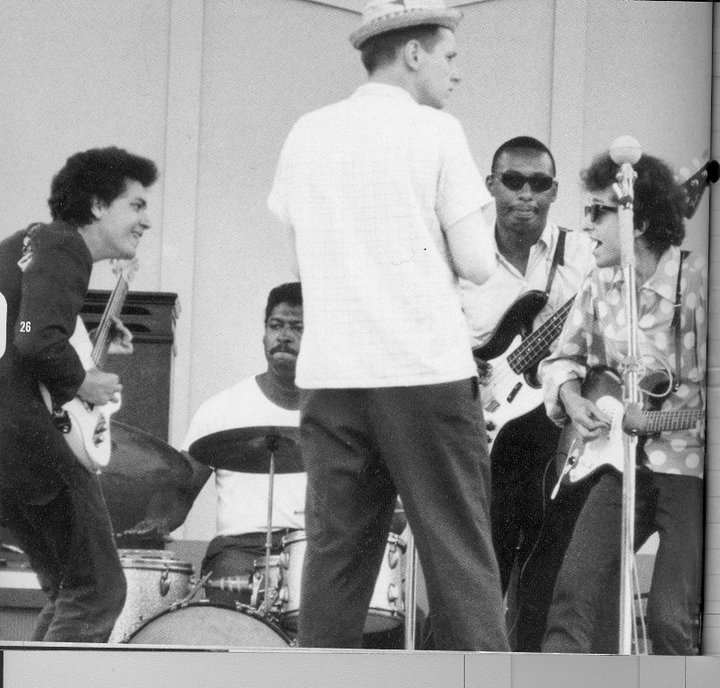

This insomniac suffered mightily through the Butterfield band’s greatly increased touring. So he quit, to form The Electric Flag (“an American music band”) just in time to debut at the historic Monterey Pop Festival of 1967, when Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and others discovered Bloomfield as a live-performance force. In 1964, he and his Butterfield band mates had been the transgressors responsible for Dylan’s notorious “going electric” at the Newport Folk Festival, in effect the birth of folk-rock. Bob Dylan shocked many listeners at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival by playing with an electric band including Michael Bloomfield (far left) on electric guitar and Bloomfield’s Paul Butterfield Blues Band mates, Sam Lay on drums and Jerome Arnold on bass. Courtesy Sony/Legacy

Bob Dylan shocked many listeners at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival by playing with an electric band including Michael Bloomfield (far left) on electric guitar and Bloomfield’s Paul Butterfield Blues Band mates, Sam Lay on drums and Jerome Arnold on bass. Courtesy Sony/Legacy

In Sweet Blues, Country Joe McDonald (famous for his “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” at Woodstock) recalls noticing Bloomfield’s peculiarly intimate relationship to his instrument: “He was like a noodle. It was the way he became at one with his guitar, the way he bent over it, like his fingers melded into the guitar. He’s not playing the guitar, he is the guitar.” But Bloomfield could not hold together the Electric Flag, which was poisoned by excess drug use. After one album with some dynamite performances, they broke up.

The cover of the lone studio album by the genre-crossing “American music band” that Bloomfield led long enough for it to make a stylistic impact that echoes to such current rock-blues-with-horns bands such as The Tedeschi Trucks Band. Courtesyeuescuto.com.br

Kooper seized the opportunity, wanting to capture Bloomfield unadulterated. He booked a Columbia Records recording studio which would produce the best-selling album Super Session. But this proved also symptomatic of Bloomfield who, after one night’s recording, went sleepless again, simply went home with a note on his hotel bed. Kooper scrambled to find another guitarist to finish the session, and Stephen Stills came through. Bloomfield’s solution for insomnia proved ominous. He took heroin to control his overactive brain, explains Electric Flag singer and long-time friend Nick Gravenites. Here’s Bloomfield wringing the blues out to dry on “Albert’s Shuffle” from Super Session. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UHFPVOEKEfA

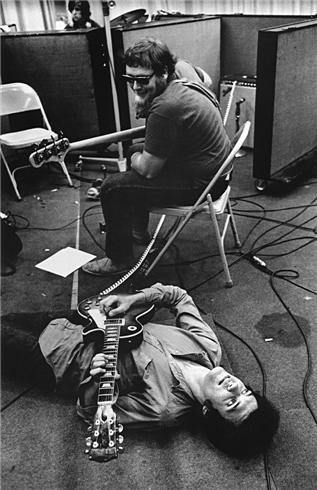

My favorite photo from the “Super Session” date was of Bloomfield lying on the studio floor, doing everything he could with his body and mind to get the music he wanted out of this Gibson Les Paul. He also did the session barefoot because he was suffering from a very painful ingrown big toenail, aside from this ongoing insomnia. That’s some kind of blues, but even a guy with his quirky sense of humor was probably too embarrassed to write a blues about it. That’s really the blues. Bassist Harvey Brooks offers encouragement. Courtesy luizwoostock.blogspot.coml

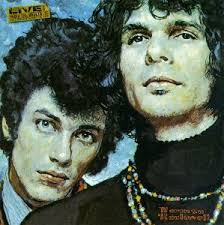

But the Kooper-Bloomfield partnership produced some expansive and meaty live recordings afterwards — and enough fleeting hype to get famed Americana artist Norman Rockwell to paint the pair for a live album cover (see below). Norman Rockwell’s painted cover for “The Live Adventures of Michael Bloomfield and Al Kooper.” Courtesy popscreen.com

Norman Rockwell’s painted cover for “The Live Adventures of Michael Bloomfield and Al Kooper.” Courtesy popscreen.com

Among the most character-defining of Bloomfield’s later recordings included here is Bloomfield’s puckish little self-portrait called “I’m Glad I’m Jewish” with a bluesy mock-boast, “you know those Christian girls can’t leave those Jew boys alone.” He understood his gift, and its fundamental and deep human appeal.

The final disc, a DVD of Bob Sarles’ new film Sweet Blues is filled with the precious few film clips of Bloomfield playing and talking, and a litany of testimonials and memories from Dylan (“He was the best guitarist I ever heard.”), B.B. King, Carlos Santana, Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, and Grateful Dead singer-guitarist Bob Weir: “The way he could bend a note and then do a vibrato was way beyond the limits of human ability at that time.”

As a teen, Bloomfield fled to the South Side blues scene and defied his “brute” of a father who called Michael’s guitars “fruit boxes” and would literally smash them to pieces. He poorly understood the gifts of a son who learned to play right-handed guitar despite being left-handed. His son could recall whole pages of books, word for word.

“But the best thing about him he was fearless,” says former Butterfield band mate Elvin Bishop. Yes, that’s what allowed him to dive into his bottomless passion, to go for broke and the musical outer limits.

There’s also telling and touching stories from his brother Alan, his ex-wife Susan Beuhler and his mother Dottie Shinderman, to whom Bloomfield remained very close to his whole life.

The film’s only flaw is not addressing the significance and impact of the composition “East-West,” instead using it as a musical backdrop to that point in the Butterfield Band’s career. As John Coltrane’s great drummer Elvin Jones once said of “East-West” on a Down Beat blindfold test: “Very well done. This has a nice feeling. I’d give that five stars.”

After Bloomfield’s gradual demise in the late 70s, Dylan finally located him in 1980 on a West Coast stop, almost as an intervention. He persuaded Michael to come out and play at his gig. From that concert we hear — on “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar” — how Bloomfield almost doesn’t make it out to the stage after Dylan’s long introduction of him.

And then, a few months later, Bloomfield was found mysteriously dead in his car, from a mixture of drugs he didn’t ordinarily use. Al Kooper heard the news and says, “I just played the Super Session record all night long.”

Perhaps he was trying to somehow bring his musical brother back to life. Kooper finally got the real opportunity to conjure Bloomfield, from his head to his heart to his hands.

____________________

* Bloomfield box set photo courtesy musicfourheart.me. Bloomfield grave stone courtesy findagrave.com

1 In 2011, Rolling Stone magazine declared Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” as number one among “the 500 greatest songs of all time.”: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/lists/the-500-greatest-songs-of-all-time-20110407/bob-dylan-like-a-rolling-stone-20110516 Dylan instructed Bloomfield: “No B.B. King shit” for this song. The guitarist showed great restraint on “Rolling Stone,” mainly playing a rusty-edge rhythm guitar shuffle (He literally had to wipe snow off his guitar, as he showed up with his Fender Telecaster strapped over his back, without a case).

You hear more of Bloomfield’s characteristic blues lacerations on the following tune on Highway 61 Revisited: “Tombstone Blues.” The guitar highlight of Highway 61 is “Desolation Row,” of course. I’m pretty sure most of the elegant acoustic-guitar filigrees are by Nashville studio ace Charlie McCoy. But it sounds at times like three guitars (including Dylan’s strumming), so I think 22-year-old Bloomfield was adding some fills, and learning on the fly from the master country picker.

Al Kooper’s curatorial choices on the new Bloomfield set are almost flawless although my quibble is his opting for the breezy medium-tempo “Blues with a Feeling” to the exclusion of “I’ve Got a Mind to Give up Living” (from East-West) — only a half-minute longer in length – but braced by two of Bloomfield’s most piercingly soulful guitar solos. The latter song was a slow blues which is a strong measure of a blues player, just as a ballad is for a jazzer, because both modes are about quality and depth of expression more than speed chops.

2 Bloomfield signed with Columbia in 1964 but fitfully pursued his career as a leader with the large label. This new set greatly expands on the 1994 Bloomfield CD Don’t Say I Ain’t Your Man: Essential Blues 1964-1969 and Bloomfield: A Retrospective a two-LP anthology from 1983 which never made it to CD. Kooper lobbied for years to produce a set to do Bloomfield justice. This writer did as well, in my very first blog post on NoDepression.com in 2012. Sony/Legacy seems to abide by ten-year reissue intervals.