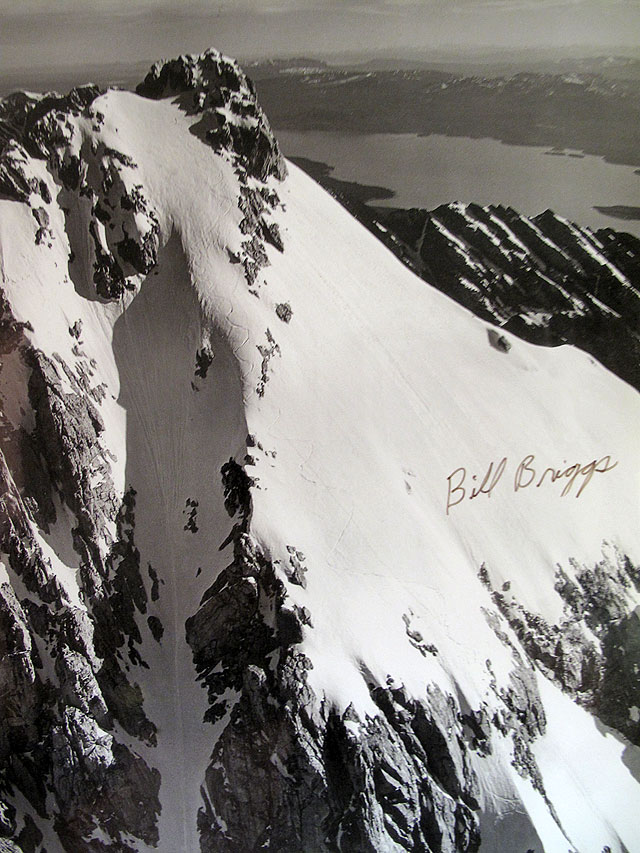

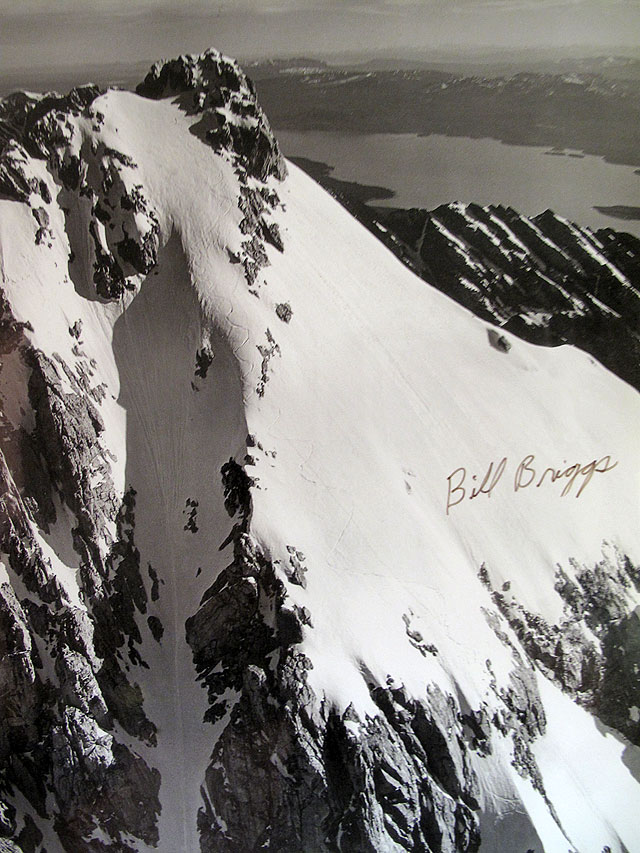

Notice mountaineer Bills Briggs’ ski tracks zig-zagging down from the summit of The Grand Teton, an unprecedented feat he accomplished on June 15, 1971, a few years before I climbed with him. Photo courtesy of Virginia Huidekoper.

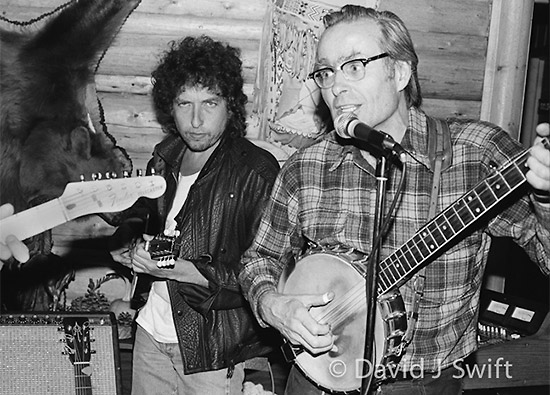

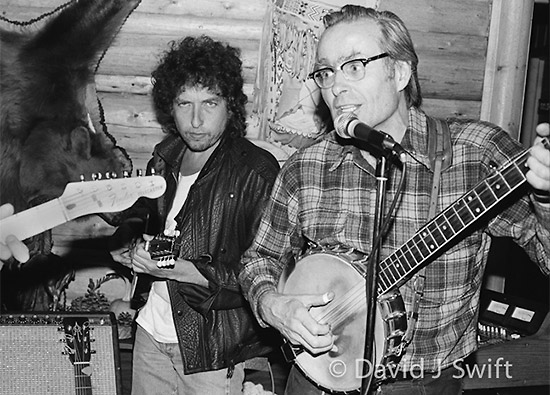

Do I start by saying that Bob Dylan once backed up Bill Briggs on mandolin — at a wedding reception performance — while Bill sang and played banjo? Ah, that’s a story for the other side of the summit.

Bill Briggs seemed like pretty much a regular guy, at first glance. But he held a coiled, panther-like tension in him, ready to spring. I picked up on this gradually as he gathered the party of climbers he would lead up Mount Moran in the Tetons in late August of 1976. He was the oldest guide I’ve ever climbed with in the Tetons but none of them ever had this type of veiled energy.

I mean what other dude was crazy enough to do what he did on The Grand Teton, which serious climbers considered the American Eiger back in the ’70s. 1 Aside from the great mountain faces in Yosemite, it remains perhaps the most iconic mountain in the continental US, among climbing challenges.

Go ahead, climb The Grand — I mean with skis on you back. When you reached the summit put the skis on….

Nobody had ever come close to flirting with that as a dream that I know of. It took slightly geeky, bespectacled but sinewy Briggs. But wait, there he stood with a physical disability, of sorts.

As Louis Dawson wrote, in his excellent Briggs profile: “Briggs entered the world without a hip joint, and at two-years-old surgeons chiseled out a socket in his pelvic bone. Hinting at his deep and unorthodox spirituality (he practices the controversial religious philosophy of Scientology), Briggs recalls, ‘It was during the hip operation that I took this body. Whoever was there before me was pretty bright, he already knew the alphabet and he could count — so I took the body and suddenly I couldn’t do the numbers or abc’s. Since I was expected to already do those things,’ he continues with laughter, ‘I had to learn quickly.'” 2

But that’s as far as I take the “crazy” talk because he proved this seemingly unimaginable feat wasn’t impossible. I saw no trace of craziness in the man, just a barely contained creative energy. In retrospect I see this manifests itself in how a person finds an outlet, because creativity is a strange force when you think about it, like a slightly untamed spirit within that prods, fires and even directs the imagination. It whispers in the ear and the sound is surprising but oddly familiar.

The first thing is to understand the improbable things he accomplished before we or anyone else imagined anyone possibly could.

In that sense, he may be a role model I hadn’t thought about for a while until a few summers ago, for some reason. I didn’t realize until recently that 2010 marked the 40th anniversary of his devil may care plunge down the Grand.

When I failed to track Bill down I despaired of ever seeing that image again so it wouldn’t be me making up a tall one.

Of course Googling him never occurred then — cuz I was caught in a 1976 time warp, and snail mail seemed the only way.

I contacted his former employer, Exum Guide Service in Jackson. No dice….

I knew he’d been the first and only man to have skied down the precipitous peak of the mighty Grand Teton, and here he was leading me on a climbing excursion.

So as we set out toward the lake we needed to cross to get to the foot of Mount Moran, he was friendly and affable, but mainly focused on the daily business of earning his keep as a professional mountaineering guide with the Exum at America’s most picturesque mountain range. We had a nice group of people including Sharon Salveter, a red-tressed climber as smart as she was fetching.*

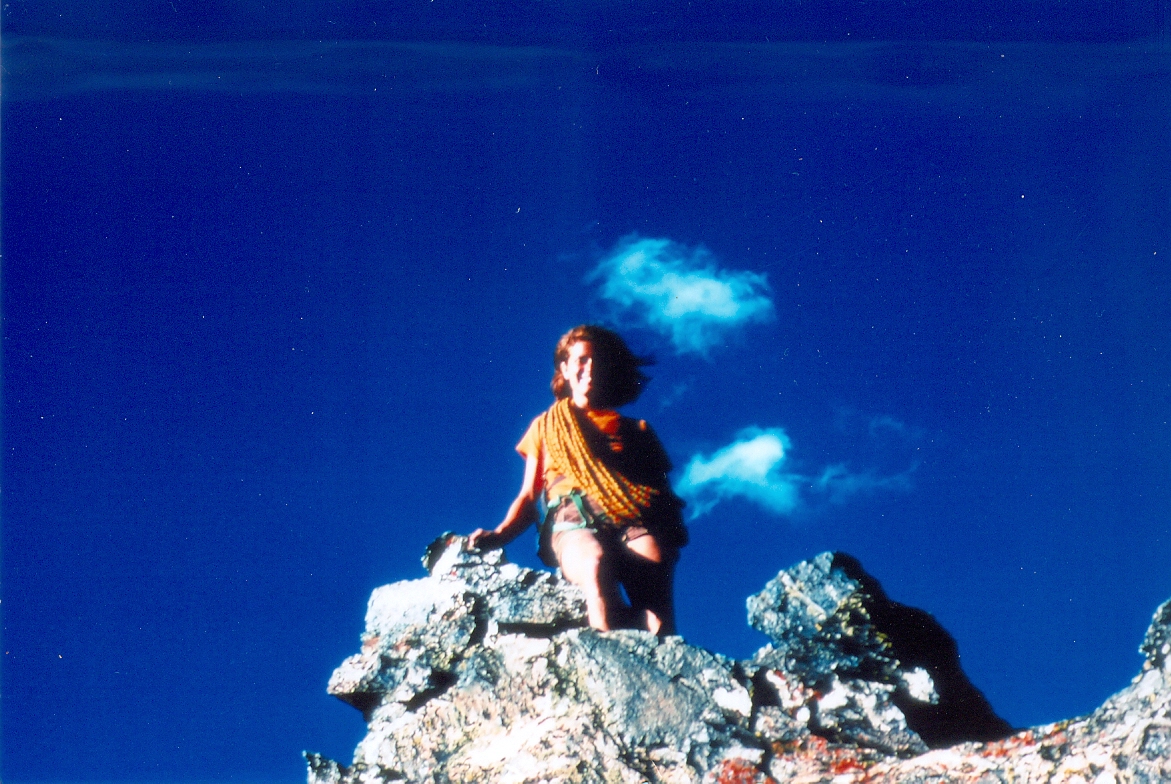

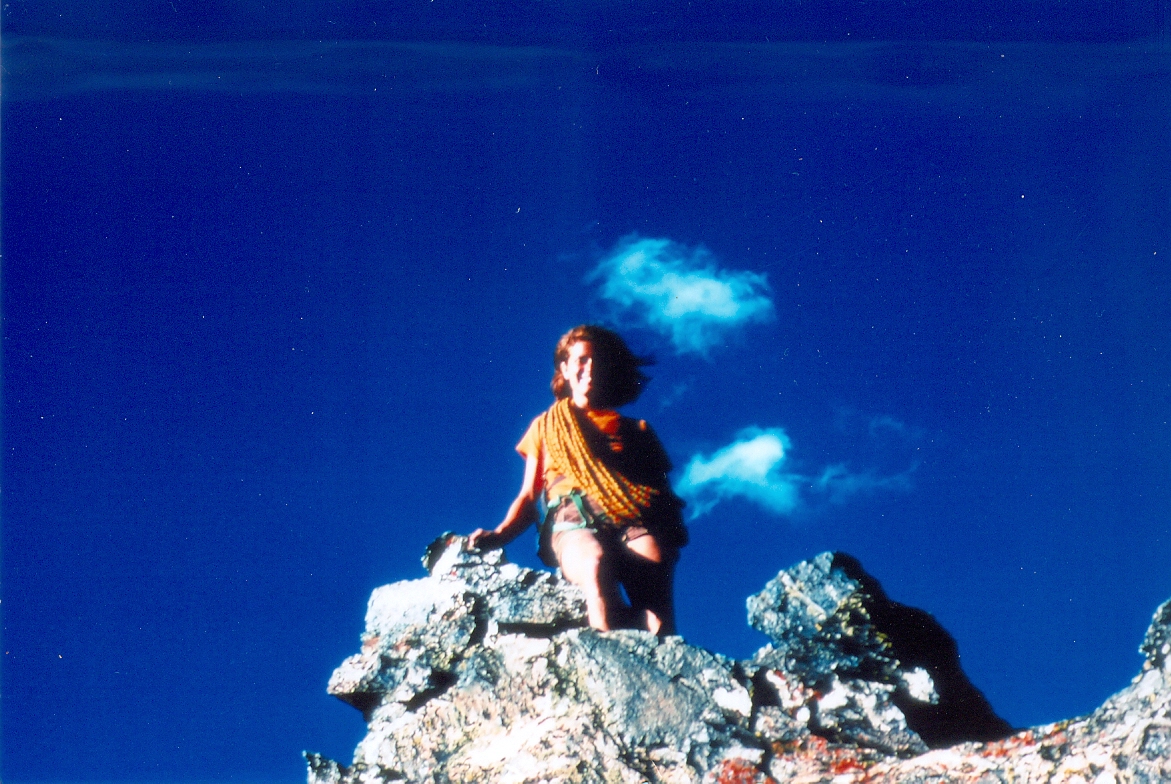

Sharon Salveter smiles down encouragingly as I struggle up a pitch on Mount Moran

And it was partly a certain awe with the idea of climbing with this guy, who amounts to a pioneer in mountaineering and what today is called extreme sports.

Despite his focused professionalism, Briggs relaxed when we made bivouac the first night of the climb. As we had our dinner meal, he was hardly shy about sharing his knowledge and wisdom, as is evident in the photograph of him holding court at that bivouac with Sharon and me listening raptly.

I don’t remember a lot of specifics about what he said, because it was so long ago. I felt intrigued but I had not yet developed the reporter skills I would later in the decade that would lead me to a career in journalism. So I took no notes and did not press him about his most famous feat which I figured he was tired of repeating.

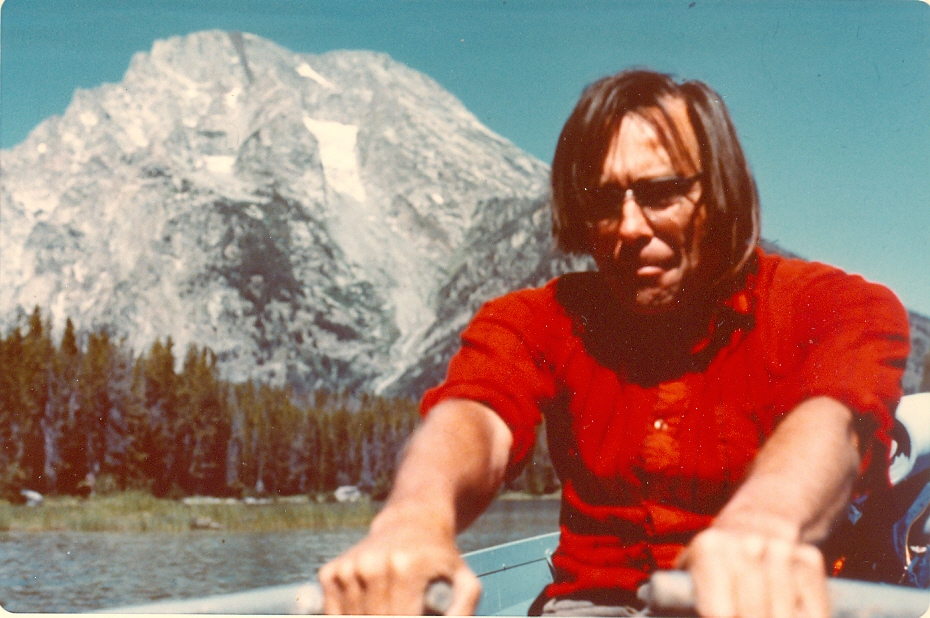

I really don’t think I realized at that time that he had pulled off that remarkable accomplishment just a few years earlier in June 1971. But I have vague recollections of him speaking about various climbing exploits and about the challenge ahead of climbing Moran. I think I would’ve remembered if he had talked about his love for music and playing the banjo. Despite being by far the oldest person in the in the party, he did most of the rowing across the large lake most of the rolling cross the lake though Sharon pitched in too (No I didn’t feel like a Sultan, perhaps I should’ve.) .

As Briggs rowed a long, dank lock of dark hair kept falling over his face and I also noticed a faintly maniacal gleam in his eye. Just his way of concentrating, I thought to myself. And yet now recalling him sustain that demeanor — and now knowing that he is a sort of Americana type singer and string player — he strikingly resembles the brilliant and certifiably eccentric North Carolina singer-songwriter guitarist Malcolm Holcombe, who has the same type of wandering hair lock.

Jackson Lake is the largest glacial Lake in the Teton Range and the second-largest natural lake in Wyoming. Once traversed we also had to cross the immense Moran Canyon to reach the foot of our destined climb. Briggs had explained to us the length of this long approach and we understood that he knew the importance of timing the climb. So we didn’t want to distract him from keeping the proper pace.

He explains in his interview with — that more difficult than his spectacularly daring downhill ski of the Grand Teton was getting the timing right — so that the conditions were perfect to make a survivable ski attempt. That same sense of precise purpose was at work as we approached Moran. After all he had our lives in his hands. Moran is a moderately difficult climb I had progressed to that level of difficulty in this my fourth summer of climbing in the Tetons, and third as an Exum-trained climber. Nevertheless, Morton Moran (12,594 feet) has no easy route to its summit, according to the Bonney guide.

As we scrambled up Mount Moran’s foothills, we encountered this view of the site of our guide’s extraordinary skiing feat, a few years earlier. The Grand Teton is the highest peak in the photo. Teewinot Mountain is the broad-faced peak hugging up against The Grand (and often confused for it).

The end of the boat trip was in Moran Bay once called spirit they named for the cry of “Old Joe!” — one of the first party of climbers — which remarkably repeated at intervals of 30 seconds court and these sounds echoed It “re-echoed a thousand times reaching higher and higher along the mighty wall, till faint goblin whispers from the cold icy shafts and spectral hollows answered back clicking notes and hisses, but distinctly always the words ‘Oh Joe!’” ?Bonney recounts. 3

Perhaps the spirits of thousands of long gone prehistoric hunters have something to do with that haunting echo.

And had we heard it ourselves perhaps it would’ve had something to do with the him and the crash of a DC three plane off course with 24 missionaries which hit the Northeast Ridge of Moran at 11,000 feet (“about level with the lower end of skillet glacier handle on November 21 of 1950 all aboard were killed. Impossible to remove the bodies or wreckage, this regular climbing route was closed for five years until the remains had weathered away. Even today remnant remnants of the plane startle climbers unaware of the accident.” 4

Briggs, perhaps by training, steered us clear of the macabre site. Another part of the aura of the Tetons is an extraordinary weather changes, In the picture below, notice how Briggs (left) and I lunched in stripped-down garb. At the bivouac that evening (see first color picture, above) we huddle in our down jackets.

The biggest drama of the climb is the sheer exposure of a long pitch shortly after the descent from the summit. it’s in the negative 90° realm with some distinct overhang drops.

As the light begins to fade over the Teton range, we got a view of how threatening Mount Moran can be, especially for a failing airplane, like the one that crashed here in 1950.

But we were all securely belayed so it was just what I call a phenomenological thrill because once we got full awareness of her situation the new we were safe.

You can also judge the pitch from my photo of Richard rappelling.

Bill’s other brush with true greatness involved no vertigo, only a hobo (or, in a more sardonic argot, a rolling stone 5) named Bob Dylan. Here’s how Briggs described is unlikely gig with Bob, in an interview with Griffin Post for Powder.com, an online skiing publication:

“He played with me [laughs]. No, I don’t know Bob. The situation was it was a wedding reception and he was obviously not enjoying it. You get the feeling, (Bob was thinking) I have to be here but this is not what I want to do, type of thing. (A friend) knew Bob and talked to him and said, ‘Would you like to play?’ I think what he replied was, ‘Yeah, as long as I don’t have to sing.’ It gave him a chance to get out of the social scene and all he had to do is play mandolin behind the pick-up country band. You get the impression that he enjoyed doing it. I got the impression that he really did appreciate having the chance to play and not have to perform. It made it a good night with him.”

Banjoist, singer and mountaineer Bill Briggs accompanied by a hobo from Hibbing, Minnesota on mandolin. Courtesy of David J. Swift.

I’d struck up enough of an acquaintanceship with Sharon Salveter that she invited me to (chastely) share a cabin she had rented for the night after climb. We recollected our experience of Moran and Briggs. We perused the poster size photograph of Briggs’ remarkable skiing feat, which he had autographed for me. Then Sharon settled in for a sound and well-earned night’s rest. As for me, I struggled to sleep, despite the rigors of the climb.

Years later, I carelessly lost the precious poster during one of my residence moves.

But the image remained etched in my memory until I happily came across it on the Web, as you see above. Crane your neck and imagine being local newspaper reporter Virginia Huidekoper when she took that shot of Bill’s ski tracks.

That wedding gig was one of Dylan’s brushes with greatness.

___________________________________

* Salveter would go on to earn a PhD. in computer science at the University of Wisconsin — Madison. She is now a senior lecturer in computer science at the University of Chicago.

1. See Climbing in North America Chris Jones, University of California Press, 1976, 314. Briggs musician anecdote (special thanks to my sister Nancy Aldrich, who gifted me the Jones book for Christmas 1976).

2. http://www.wildsnow.com/articles/bill-briggs/bill-briggs-william-biography.html

3. Bonney’s Guide: Grand Teton National Park and Jackson’s Hole Orin and Lorraine Bonney, 1966, 52

4. ibid Bonney’s Guide, 62

5 I’m intrigued by changing rhetorical usage in songwriting, here about the peripatetic downtrodden. (Pre-sexy) Rod Stewart once sang Dylan’s 1963 “Only a Hobo”: “To wait for your future like a horse that’s gone lame/ To lie in the gutter and die with no name.” By contrast, Dylan in 1965 sang, “How does it feel, to be on your own, with no direction home, like a rolling stone?”

Both use unforgettable similes. One paints a somber picture of social realism, the other a more abstract, acidic challenge to a complicated and conflicted middle class. Placed together, they form a clearer picture of their times, and when unassuming troubadours like Briggs made a precarious living guiding middle-class guys like me up mountains. What of less-gifted hobos? What changed between 1963 and ’65?

How does it feel, today? Does anybody sing a hobo’s song?

All photos of the Mount Moran climb are by Kevin Lynch. I believe the photos which include me are by Sharon Salveter, but your blogger’s failing, middle-aged memory can’t be sure.

Like this:

Like Loading...