Courtesy Trouser Press

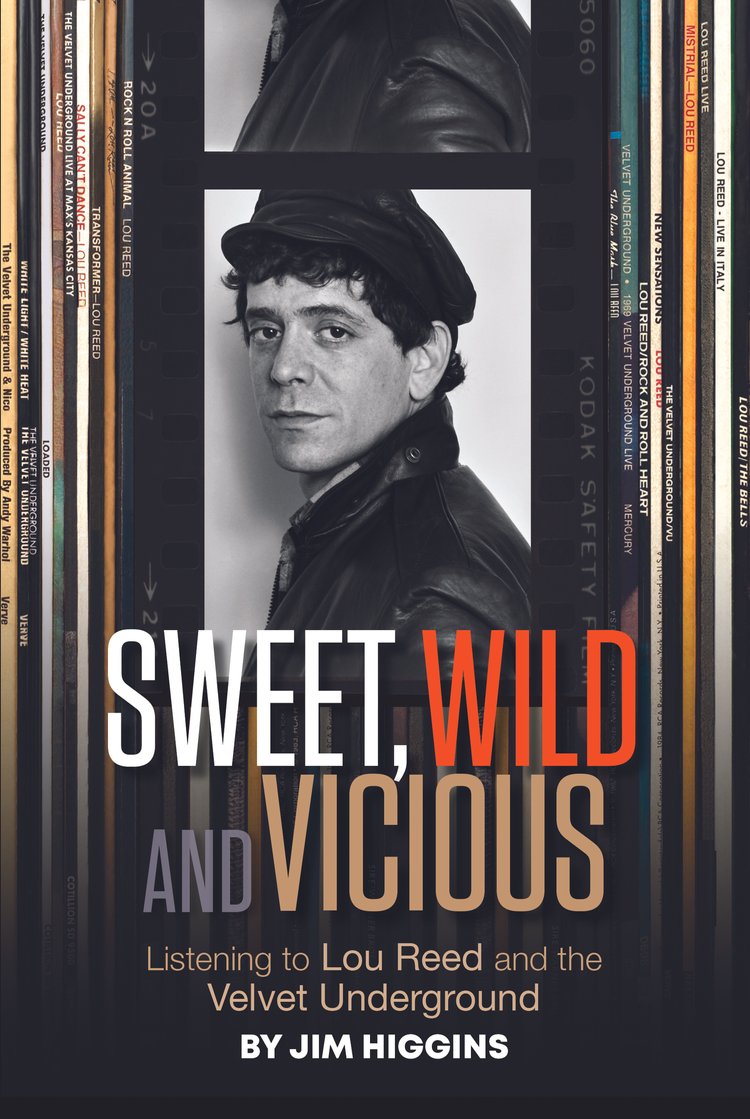

Sweet, Wild and Vicious: Listening to Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground,

By Jim Higgins, 250 pages, paperback and e-book, Trouser Press, $20 *

Lou Reed (1924-2013) was the musical bard of New York as the quintessential East Coast big city. He’s worth comparing to Bob Dylan, the great musical poet from the Heartland – who’s certainly America’s greatest poet-musician. Still, it’s worth pondering such a comparison (Brian Wilson might be a West Coast comparable).

In his new book Sweet, Wild and Vicious: Listening to Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, Jim Higgins assesses Lou Reed in depth and, for me, even invites such comparisons. Thus, he provides a deepening sense of a major artist’s experience and interpretation of his part of America, the oldest and most diverse part, no less.

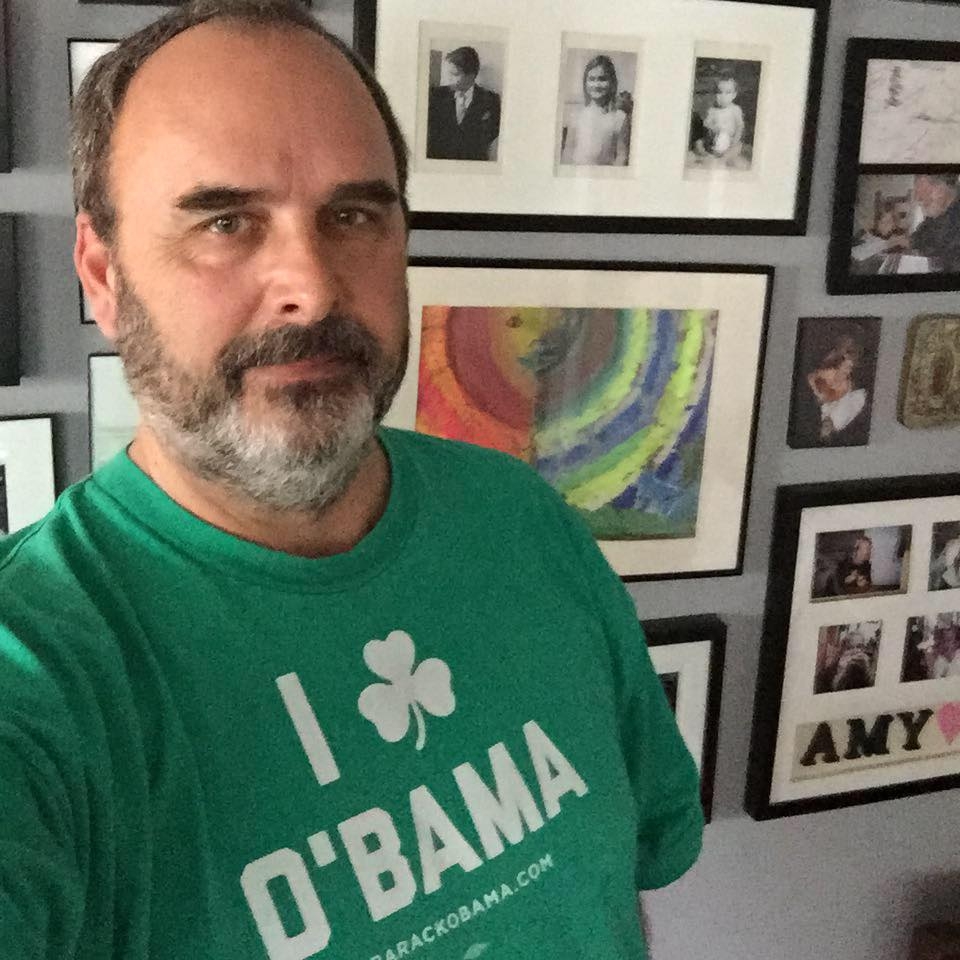

Higgins is well known in Milwaukee as the book page editor and an arts writer for The Milwaukee-Journal Sentinel. He previously authored Wisconsin Literary Luminaries: From Laura Ingalls Wilder to Ayad Akhtar.

I am a Lou Reed fan but didn’t fully appreciate him until I read this book. Now I’ll continue to explore more fully his oeuvre. I’ve discovered a couple fabulous Reed albums I should’ve known about, The Bells, with the great jazz trumpeter/world-musician Don Cherry and The Blue Mask.

Higgins is a consistently insightful and skilled writer. For example, regarding The Blue Mask, he comments on Reed and Robert Quine on the first two songs: Hear “how gently and beautifully those two famously noisy guitarists are playing. It’s like their making lace out of quarter notes.”

Though a supreme wordsmith Reed invariably realized how important the music was to a song’s success. His singing, sometimes stentorian, had a surprising range of expression, and his guitar was nearly comparable to, say, Neil Young’s as a singer-songwriter’s adjunct. 1

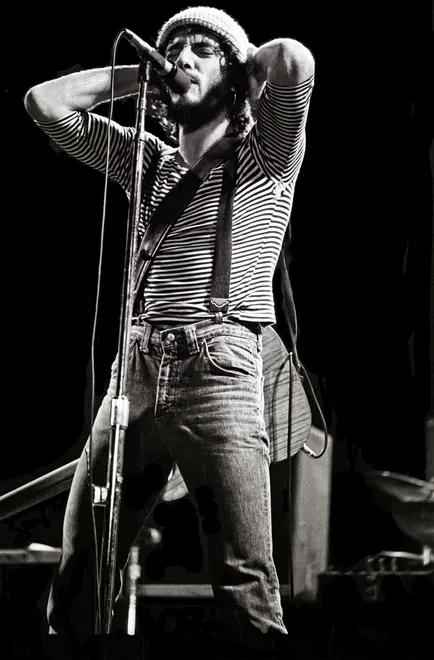

Lou Reed’s guitar was an important adjunct voice to his art. Courtesy Billboard

So, hats off to Higgins. However, with such a labor-intensive, inclusive survey of a long music career — 50 albums! — the author at times becomes rather workman-like, amid the weeds. He understandably spends a lot of time with specific songs, separating the wheat from the chaff and commenting on the chaff, perhaps fearing he’ll otherwise come off as too hagiographic?

He needn’t worry. His praise and criticism read largely as astute and he often qualifies by saying it’s his opinion or taste choice. And he dutifully acknowledges his predecessors: especially Reed biographer Anthony DeCurtis, and “dean-of-critics” Robert Christgau. So, he’s a knowledgeable and humbly likeable guide who educated me in the substantial depths of Reed’s extensive catalog. His appreciation of the ground-breaking Velvet Underground as a musical band is especially enlightening.

However, I wanted a bit more courage of convictions. He says the title song of Street Hassle “was Reed’s most deliberate attempt at a masterpiece to that point.” His detailed description almost amounts to an argument for “masterpiece.” Along with his comments, I’d call “Hassle” a masterpiece. The extended cello motif beautifully weaves together an 11-minute, three-movement suite, an urban tragedy: the first movement “Waltzing Matilda,” is romantic, the second, “Street Hassle,” cold-eyed about fatal “bad luck,” the third, “Slipaway,” a wrenchingly authentic cry over lost love. Using (uncredited) Bruce Springsteen’s husky voice to extend the chilling second movement feels brilliant, as a contrasting sort of monotone witness, which allows Reed’s voice the drama of spilling his heart in the last movement. Plus, Reed’s use of the phrase “slip away” takes on three very different meanings in each segment. Yeah, masterpiece, worth rehearing repeatedly.

Lou Reed and “The Banana Album” that made him famous as a cult figure, at least. Courtesy Newsweek

Higgins does fine justice to the career-launching “Heroin” from 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico, the album that secured the band’s fame. Rock music never had (nor has since) a more laceratingly honest and audaciously immersive evocation of drug addiction. And delusional: “and I feel just like Jesus’ son.” Higgins narrates the song’s tell-tale form: “ ‘Heroin’ begins as gently as a folk song, but speeds up four times in imitation of the rush the addict feels, ebbing each time to a doubled statement of defeat. (John) Cale’s electric viola drones throughout, until it shatters into shrieks during the final rush.” For me, a stone masterpiece, revealing early Reed’s courageous genius.

At times Higgins does go out on interesting limbs, asserting that Mott the Hoople’s take on “Sweet Jane” on All The Young Dudes is the best version of a signature Reed song. However, he then extolls The Cowboy Junkies’ far more tender rendition of “Jane,” so you have your pick of several recommended interpretations, another valuable critic’s task of digging through the music catalog. One provocatively bouncing limb he hits too timidly: He could’ve praised the potency of the song “Sex with Your Parents (Motherfucker), Part II” on Set the Twilight Reeling, which is a laugh-out-loud skewering of hypocritical right-wing holier-than-thous. More controversy over it would’ve been something to see.

As DeCurtis reported, Laurie Anderson’s tribute to her spouse in Rolling Stone for the Rock n Roll Hall of Fame is extraordinary, eloquent and fascinating though she says “he was kind, he was hilarious, he was never cynical.”

She must’ve cured him of that unless he was way misunderstood at times. And it’s amazing that Anderson apparently, in his eyes, was a woman “of a thousand faces,” whom he wanted to marry, as referenced in “Trade In” on Twilight. Given that desire’s impossibility she must’ve been a miracle soul mate. Over years before, Reed did unforgivable things to people he loved and treated sweetly just as quickly.

Anderson knew his badness, or of it, but their love lasted for 21 years until his death.

Also, I think the title song of Twilight hardly “strains for profundity,” as Higgins says. In a simple arrangement, it’s about learning to let go of regrets, accept himself “as the new found man” and “set the twilight reeling.” It may be too poetical for some but it takes plenty for anyone, especially this complex and troubled, to accept himself.

I understand the new found man as the man in the historical “new found land” ie: America. Like his image of Anderson, it’s a bit self-mythologizing but also humblingly honest. It’s also self-absolution, but saying as much to us. That’s all very Lou Reed, to me. The album’s most telling, acidic and profound song is “NYC Man,” with Oliver Lake’s lovely horn arrangement. It’s much more confessional than the title song, so Reed’s not really hiding behind his poetry, even if its dense, literary text is Dylanesque.

Among the book’s distinctive features is “Children of The Velvet Underground,” persuasively surveying the many artists influenced by Reed’s path-forging group, such as David Bowie, Jonathan Richman, Sonic Youth, Nick Cave, Yo La Tengo, and Milwaukee’s Violent Femmes.

Another group of valuable features (especially for iPod users) involves Higgins combing through the repertoire to come up with “One Hour with Lou Reed” in the 1960s (The Velvet Underground era) and likewise through the ‘90s, by choosing exemplary songs of each decade.

Three of his selected songs for “The ‘90s and beyond” are from Magic and Loss, an album serving as a nakedly poetic elegy to the agonizing cancer death of singer-songwriter Doc Pomus, seemingly the father figure in Reed’s life. Among the album’s numerous luminous moments Reed likens radiation treatment to “The Sword of Damocles hanging over your heard,” giving the man’s death mythical resonance. Higgins however, asserts that Magic and Loss is merely one half of a great album. Hmm. I just know when I first heard it, Reed carried me right through and, by its end, I was stunned into silent reverie, a bit like hearing “A Day in the Life” for the first time. Deeply shaded with superb writing, this underappreciated album is a chiaroscuro masterpiece. Or perhaps “classic” is better if “masterpiece” seems too exalted a term for such a muted work.

Lou Reed and spouse Laurie Anderson. Courtesy Medium

Reed’s best songs and albums feel as real and poetically moving as any American sing-songwriter of his generation, in that sense comparable to Townes Van Zandt, or more recently the more storytelling James McMurtry, very different stylistic geniuses of yet another fecund American region of singer-songwriters, Texas.

Being married to an atmospherically avant musician-artist like Laurie Anderson helped Reed understand himself as a kind of literary musician-artist of substantial merit. He was unafraid to do a somewhat over-reaching album-length interpretation of Edgar Allan Poe (The Raven, 2003), choked with notable actor-reciters and guest artists. To be sure, this was Lou Reed’s Poe, nobody else’s. As Melville said, “It is better to fail at originality than to succeed at imitation.”

Higgins’s valuable book expands the lens of perspective in our experience of our best songwriters portraying and illuminating America.

____________

* The Higgins book is available at Boswell Books, 2559 N. Downer Ave., in Milwaukee and directly from Trouser Press. Here’s a link to the author’s May reading from Sweet, Wild and Vicious, at Boswell, with a live interview with Journal-Sentinel music writer Piet Levy:

https://youtu.be/kUdP2I-f7K4?si=Uje371AqePKLh0N0

- Higgins delves into the underappreciated significance of Reed’s guitar playing. One of his nifty sidebar features is “One Hour with Lou Reed and his guitar,” listing ten songs that showcase his guitar work. The list includes the live version of “Heroin” from 1969: The Velvet Underground Live, which Higgins suggests is his second favorite VU album after their debut album (known colloquially as “The Banana Album”).

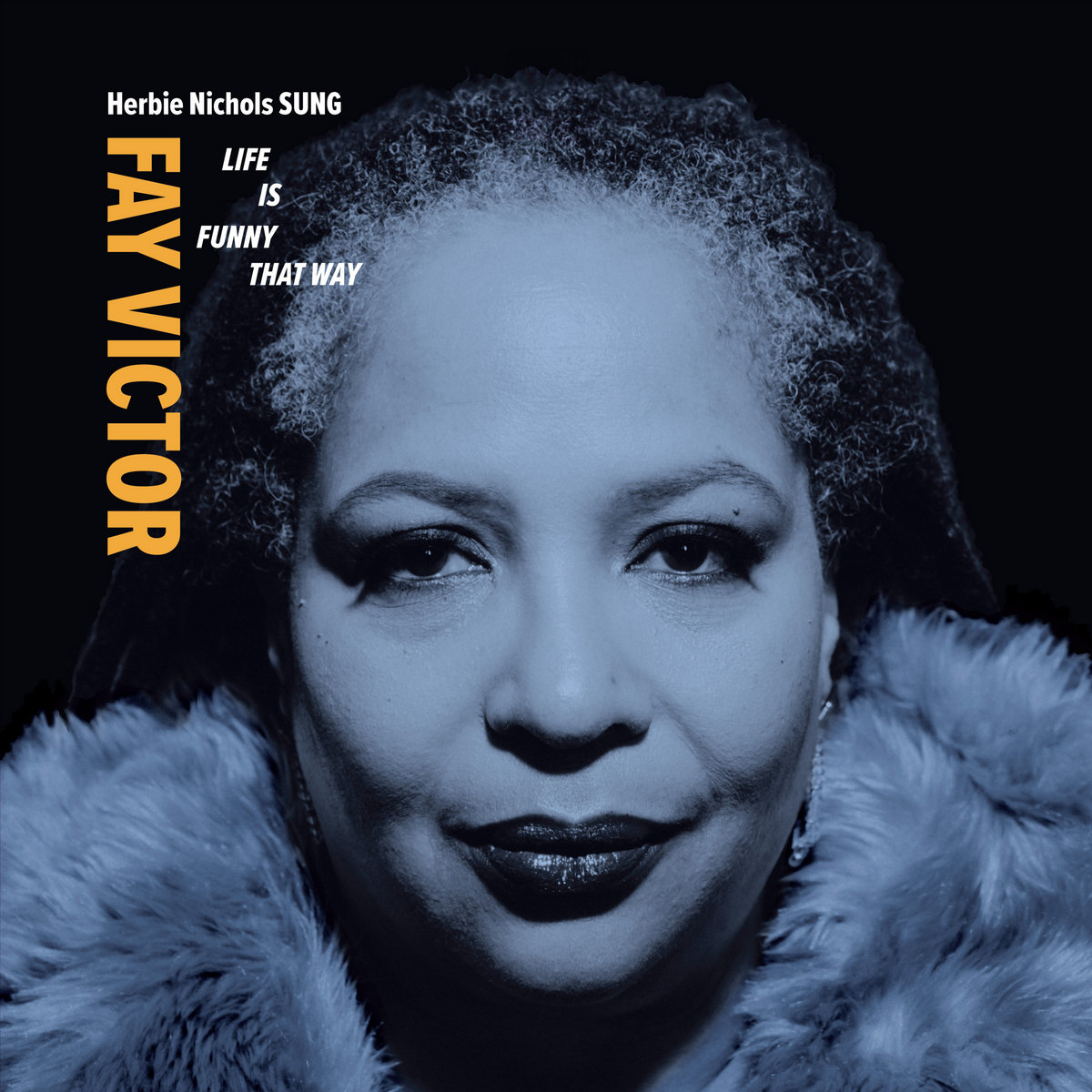

Album cover design by Jamie Breiwick.

Album cover design by Jamie Breiwick.

Bruce Springsteen (by then rather intoxicated according to a bandmember) performing after midnight at the Uptown when the bomb threat had been cleared. Photo by Robert Cavallo

Bruce Springsteen (by then rather intoxicated according to a bandmember) performing after midnight at the Uptown when the bomb threat had been cleared. Photo by Robert Cavallo