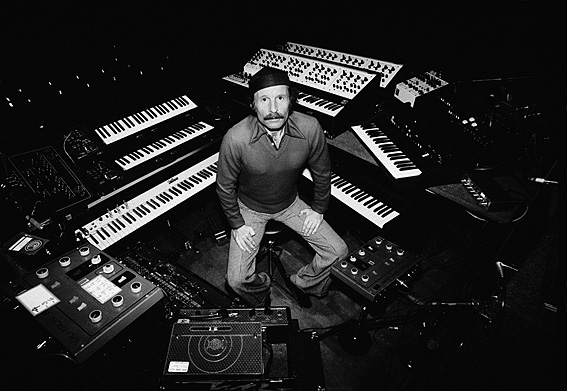

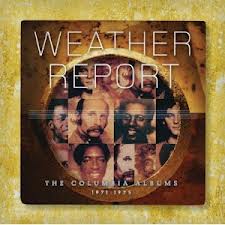

Weather Report The Columbia Albums 1971-1975

Albums included in this collection: Weather Report, I Sing the Body Electric, Live in Tokyo, Sweetnighter, Mysterious Traveller, Tale Spinnin’

Imagine recasting the musical Zeitgeist of the early 1970s as a weather report, with the music of the innovative jazz group Weather Report as the context and “soundtrack for your imagination and head.”

A weather report, of course, is a meteorological interpretation of how our planet’s natural atmospheric environment unfolds through our lives. We begin to see how aptly named this group was, a name both unassuming and yet deftly encompassing. It’s as quotidian as your dullest local drone before a daily weather map, and as an essential to one’s experience as the ceaselessly shifting winds and tides, of time and nature.

The band’s co-leader and dominant, if not necessarily best, composer Joe Zawinul, * knew what excitement lay in the shape-shifting winds. His big-idea conceptualism made Weather Report plausible as the heady soundtrack he characterized it as above, in describing the first eponymously titled album from 1971.

In the process they also opened the floodgates for jazz to expand creatively and commercially, like no group of the era. They helped usher in the jazz fusion era, but always did fusion on their own terms – and without ever using a guitar player.

Critics and music fans appreciated immediately the risks the band took, and the allure of this fresh and strange music, voting that debut Weather Report “Album of the Year” in the 1971 Down Beat magazine’s readers’ poll. That album and the last two of this collection — Mysterious Traveller and Tale Spinnin’ — also won Down Beat readers’ “Album of the Year” awards. The band would continue amassing an unprecedented consecutive run of four such awards, with the two albums following this collection’s time frame.

Let’s see how this jazz tsunami grew. A big part of their innovation was breaking free of mainstream jazz’s over-used head-solos-head format.

“We were talking about doing music that had mountains and streams and valleys and going over hill and dale,” the group’s co-founder and saxophonist Wayne Shorter recalled to his biographer. “We were trying to do music with another grammar, where you don’t resolve anything, like writing a letter where you don’t use capitals.”1.

You get a sense of the band’s openness to abstract possibility and beauty from the sinuously shifting winds suggested this stunning cover photo by Ed Freeman for their debut album.

I still don’t know what the hell he photographed — it sort of looks like a windblown clothesline strung with a few white sheets, shot in a time exposure, but I’m not sure because its beauty teases the imagination so far beyond that specific boring daily chore, like you’re hearing a weather report from Mars.

So the band concept was of a piece from the start, yet it wasn’t just about formal abstraction or innovation. The band persistently snared startling and gorgeous colors, textures, rhythms and voices. And by the time the first album’s “soundtrack” reaches the fourth tune, “Orange Lady” we plunge into human emotions. The title suggests a specific woman who possesses a quality of “orangeness,” – radiant yet tough on the outside, sweet and tart — as a human embodiment. As Zawinul’s synthesizer and Wayne Shorter soprano sax meld into a melody of tenderly keening remembrance, the experience becomes deeply grounded in the human heart, to the point of contrasting “despair and hope,” as trumpeter-composer Tom Harrell has noted of the tune.

Yet Zawinul is pushing this past the implications of a rainy, weepy Bridges of Madison County sentiment. So, while the next two tunes are titled “Tears” and “Eurydice” (named for Odysseus’s seemingly drowned lover, whom he dives to save), the music veers away from sentiment to the open air of shape-shifting Nature. “Tears” and “Eurydice” were written by Wayne Shorter, a very different but complementary sensibility to Zawinul, one that is emotionally true as it is elliptical.

This seemed like jazz impressionism, which wasn’t new but it had emerged usually in orchestral settings, like those of Gil Evans.

But Weather Report showed that a tight, sleek, grooving combo could muster transporting impressions as a new sonic magic, driven by sharp percussive textures. So contemporary music suddenly acquired some of the power of the visual and cinematic arts.

And yet, as with much modern art, the group managed a balance between a larger artful experience of exploration and basic human impulses. The group’s latent funkiness is evident in the first album’s second tune “Umbrellas.”

The second Weather Report album, I Sing the Body Electric breaks through into a more conceptually ambitious evocative arena. I remember thinking; okay they’re starting to go for it, after first album which, for all its beauty and striking moments, was sometimes too studied in its artful spaciness.

The title is borrowed from a Ray Bradbury novel, which was borrowed in turn from a Walt Whitman poem, so it has deep lineage in American literary expression as perhaps signifying a strange celebration of the self, in concert with the force of electric power as a natural element that humans come to terms with in both harnessed and unfettered forms.

Listen to Whitman:

| I SING the body electric; |

|

| The armies of those I love engirth me, and I engirth them; |

|

| They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them, |

|

| And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the Soul. |

|

1

The passage is sort of the inverse of a spiritually and mentally dying King Lear, who raged at the lightning storm railing down upon him.

Whitman offers a kind of redemption for Lear and all kings who wield armies like corrupt playthings, while ignoring loving offspring in their hubristic shadow. Whitman says you love both armies and kindred as souls, electrified by your own.

We hear something like that redemptive yet unblinking generosity in the face of death, especially in “The Unknown Soldier,” the album’s opening piece. The work echoes with sepulchral voices, fallen warriors and angels. As the album’s original annotator Robert Hurwitz eloquently comments, “We are not told of the insanity of absurdity and horror of war in “The Unknown Soldier,” we already know that. Rather we’re guided through a tone picture. We share impressions. The mind wanders to the innocence of childhood, simple sweet joys to youthful mysteries, and silence and moments of wonder… To the moment of war, of tragic realization…”

From there we moved through equally evocative tours of “The Moors” and “Crystal” to “Second Sunday in August,” where we hear the majestic lyricism Zawinul is capable of, here in a celebratory mode which would become utterly festive in the group’s biggest hit “Birdland” (which immediately post-dates the spectrum of these albums).

By now the band had built up a strong following internationally, especially in Japan which seems to have cultivated a strong fixation on American culture. This is energetically evidenced by the two-CD set Live in Tokyo, recorded in January 1972, comprising interpretations from the first two albums.

Yet another breakthrough occurs with the following album Sweetnighter, where the band really gets its groove mojo. The opening tune is the 13-minute “Boogie-Woogie Waltz,” which began a bit like the sort of electric jungle music Miles Davis was exploring — a pulsing, humid atmosphere. Zawinul’s wha-wha synthesizer and Wayne Shorter’s head-snapping saxophone accents build tension. Underneath the percussion is utterly exotic: Dom Um Romao plays bell, tambourine and Chucalho; and Muruga plays Moroccan clay drums, along with Herschel Dwellingham on traps drums.

This was a new sort of world music in 1973, presaged partly by Shorter’s Super-Nova and Odyessey of Iska albums. The tune’s marvelously gyrating main riff theme doesn’t arrive until almost nine minutes in, although it’s been hinted at. The effect of the delayed payoff is a deep hook on the listener’s musical consciousness. “Boogie-Woogie Waltz” was too long to be a radio hit, as “Birdland” would become, but it proved how capably funky this band could be and (along with another new jam piece “125th Street Congress”) helped turn their concerts into part electro-impressionistic tripping, and part pure get-down.

The band was evolving far from a jazz blowing band, even if it was heavily improvisational in an entirely new way.

The year 1974 brought yet another peak — for my money their artistic pinnacle — Mysterious Traveller. This advance occurred partly, as annotator Bill Milkowski points out, due to improvements in synthesizer technology, particularly the ARP 2600, which helped Zawinul produce a more musical line on the electronic instrument, amid its shifting sonic textures.

On Mysterious Traveller, the band pulled back somewhat from the crowd-pleasing funk-outs, nevertheless infectious rhythms pull you in from the start — “Nubian Sundance” sounds like you’ve land smack in the middle of an African village amid a wondrously pagan celebration.

Then, “American Tango” zooms back across the Atlantic to a descending melody that lands as elegantly as a large sea bird, exalted by female voices and a supple backbeat, illuminated by a brief sunburst of the kind of emotionally engorged expressivity Shorter had developed on the soprano sax.

“Tango” segues to “Cucumber Slumber,” with a tempered funk groove dressed up with a sinuous bebop-ish line, which brings to my mind a soused Charlie Parker walking a sobriety test line — his stride is so stylish the officers stand back and clap, before arresting him.

But Weather Report by definition always reaches beyond terra firma, so we encounter the title tune “Mysterious Traveller,” reflecting especially Shorter’s fascination with metaphysics and science fiction.

But here the funk hook is another ingenious rhythmic configuration — one of the band’s consistent achievements was how it elevated the conventions of funk grooves to almost a Baroque intricacy. Nor does the tune’s mood try to scare you with this alien visitor as much as open your mind to the implications of its existence. It’s more akin to spirit of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but with the childlike sense of wonder having matured.

“Blackthorne Rose” is one of Shorter’s patented musical portraits of a female spirit and “Scarlet Woman” does much the same with Zawinul’s synth flair, again re-grounding us in humanity as “Orange Lady” had.

Mysterious Traveller concludes with “Jungle Book,” a tour de force of creativity and serendipity. A distant voice seems to be singing a folk song from deep in a valley. The melody and rhythmic backdrop include Indian tambura, tabla, ocarina, kalimba and, most ingeniously, a tac piano,3 which spins variations on the folk melody. Another low-tech circumstance is that Zawinul recorded the whole thing by himself overdubbing various instruments on a home cassette recorder. Zawinul’s children happened to run into his studio during this recording and their playful voices were left in — adding a real-life vibrance to this strangely enchanting creation.

Another increasingly evident Zawinul trick was singing wordlessly through a vocoder, which added a disembodied vocal aura to the wizardly mix.

Listening to the album Mysterious Traveller seems like a travel through light years, and yet it passes as quickly as a few blinks of an ear.

This re-issue version of the album includes two bonus live renditions, of “Cucumber Slumber” and “Nubian Sundance,” which prove that this ensemble was not a phenomenon of a recording studio, like many pop groups, although their style demanded and rewarded high production values.

Perhaps the driving force for the group’s imaginative elevating of coloristic detail and everyday energy is best expressed by Shorter in the liner notes of the debut album:

“Life to me is like an art. Because life has been created by an artist…some people can only relate their soul to God. They think that the soul in relation to the universe has to do with religion all the time. They can’t see any practical use in relating their soul to a table, to a bug on the windowsill, to musicians on a bandstand, or a picture hanging on the wall, or salt and pepper. You can say that’s going from the sublime to the ridiculous, but is it? It’s like saying, ‘a bird does not fly because it has wings. It has wings because it flies.’”

Weather Report has wings, concluded that first annotator, Don DeMichael.

They prove that again in the final album of this box set, which marks the approximate midpoint of the career of a band of extraordinary duration for a jazz group.

Tale Spinnin’ recasts the now maturing band concept in terms of storytelling, which has always been part of jazz’s African-American oral tradition, if not in quite so technically enhanced terms. One tune is called “Five Short Stories,” and the harmonizing Shorter and Zawinul exquisitely suggest related episodes.

But the group also tightens up their songs and percussive thrust. However, the album suffers a slight drop-off in overall imagination — compared to Mysterious Traveller. Still, Tale Spinnin’ opens with “Man in the Green Shirt,” a tune that rekindles Zawinul’s melodic knack for the celebratory buzz, which “Birdland” would soon top, in terms of mass audience connection (on 1976’s Heavy Weather, not part of this collection).

The enigmatic, green-garbed man evokes a more handsome and elegant melody than “Birdland,” evoking personal charisma, aspiration and affirmation. The stranger could be a disarmingly friendly Martian or a godlike figure, or just a colorful tourist which, of course, might be one interpretation of God, the sort of down-to-earth artist/spirit that Wayne Shorter was talking about.

______________

*Before joining Weather Report, Wayne Shorter had already established himself as arguably the greatest modern jazz composer since Charles Mingus, with his classic series of Blue Note albums and his contributions to the Miles Davis Quintet, in the 1960s.

The classically trained Austrian Zawinul had revealed compositional ambition in the 1967 album The Rise and Fall of the Third Stream and was a crucial aspect of Cannonball Adderley’s popularity. His tunes for Adderley included “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” which remarkably was a pop hit twice in 1967, first for Adderley, reaching Billboard’s No. 16 in February. Then The Buckinghams added lyrics and turned it into a No. 6 hit in August. His 1971 solo album Zawinul introduced his composition “In a Silent Way,” which would become a standard for Miles Davis.

- Michelle Mercer, The Life and Work of Wayne Shorter, Tarcher/Penguin, 2004, 142

- Walt Whitman, “I Sing the body electric,” from Leaves of Grass: The Deathbed Edition, QPBC, 1992, 72

- A tac piano is a piano prepared by attaching tacks to the key hammers, to obtain a metallic sound.

The remainder of the group’s Columbia albums were reissued in a 2011 box set as Weather Report: The Columbia Albums 1976-1982.

Like this:

Like Loading...