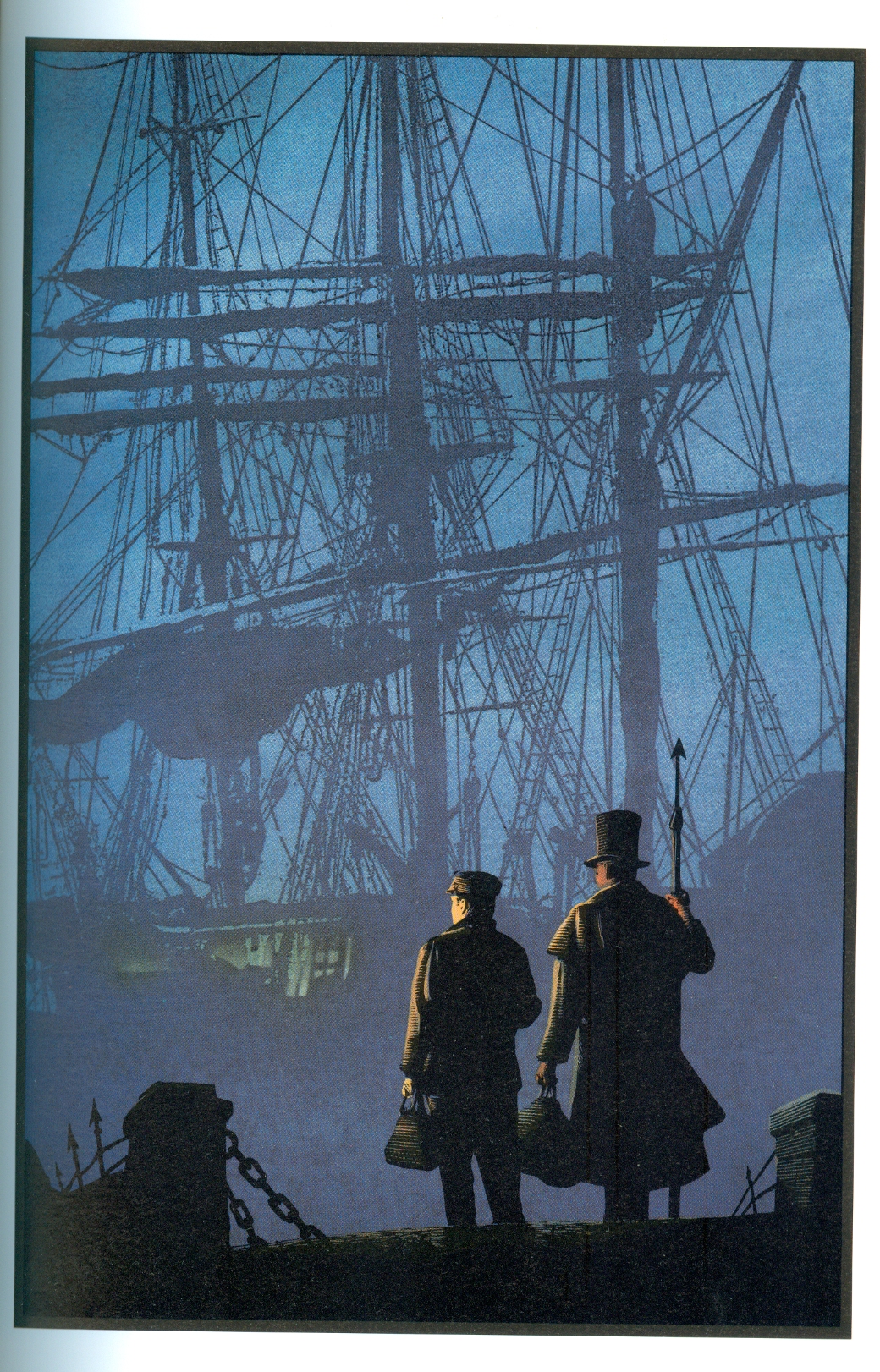

Ishamel, the narrator of Moby-Dick, and The Pequod’s first harpoonist Queequeg may be literature’s original odd couple. Illustration by Mark Summers from Moby-Dick (facing p 78) Barnes & Noble Books.

Ishamel, the narrator of Moby-Dick, and The Pequod’s first harpoonist Queequeg may be literature’s original odd couple. Illustration by Mark Summers from Moby-Dick (facing p 78) Barnes & Noble Books.

Readers of this blog will be aware of my Melville enthusiasms. (Ahoy, another white whale sighting dead ahead!)

I recently responded to a discussion of Moby-Dick on the Goodreads website, and then decided to share my thoughts here, slightly enhanced.

Julia,

I am very happy you’re giving Moby-Dick another chance. Each time I read the book I gain a fresh and amazing experience. I wonder why Ruth gave up after 50 pages – what she mainly read was the budding friendship between Ishmael and Queequeg. Is she put off by that? I find it the most humanly engaging relationship in the book, a rare and fascinating 19th-century example of a pan-cultural brotherhood, and what Leslie Fielder once called one of the great American love stories.

Ishmael reflects: “I began to be sensible of strange feelings. I felt a melting in me. No more my splintered heart and maddened hand were turned against the wolfish world. So the soothing savage had redeemed it. There he sat, his very indifference speaking a nature in which there lurked no civilized hypocrisies and bland deceits.”1

Admirably homosocial dynamics aside, I see an almost mystical love hidden in Queequeg’s request for his coffin to be built. He recovers from his fatalistic gloom, but he has intuited the demise of the ship. After all their bonding, Queequeg has also intuitively created the richly symbolic means for his best friend to survive. In the novel’s famous last scene, the wooden coffin pops up out of the water as the ship sinks and Ishmael grabs hold of it for dear life. That “orphan” survives alone, to tell the grand tale. We all have plenty to thank Queequeg for.

I recently read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and — as much as that book offers commendably provocative (but rhetorically heavy-handed, for a storyteller) portrayals of slavery’s evil — by comparison Melville’s handling of race is far more interesting and nuanced, and insightful about the complexities of multicultural relations.

Those examples range as broadly as the comic byplay of Stubb and Fleece the black cook over the hunger-crazed sharks (CH 64),* to the classic racial confrontation and masterful pan-cultural interplay of “Forecastle — Midnight” (Ch. 40), to the devastatingly cruel treatment of Pip followed by the stunningly unexpected paternal adopting of him by Ahab, even as the black cabin boy has become psychologically disabled by his trauma at the hands of his mates and the unfathomably indifferent ocean.

And of course, there’s the delightfully odd couple, Ishmael and Queequeg (who walked away from a cushy life as Polynesian royalty to adapt to Western culture while retaining his own traditions), and Ishmael’s visit to the black church service.

Nor does Melville shy from strong storytelling by avoiding possibly stereotyping characterization, with the mysterious and ominous Asian harpooner Fedallah. But Ahab’s covert hiring of him and his gang clearly reflects the captain’s deranged monomania. We all know today thugs come in all colors.

All this is amazing for a mid-19th century author, and set a cosmopolitan standard to this day and sociologically explains part of the book’s greatness.

Further, the novella Benito Cereno brilliantly demonstrates how Melville dramatizes the tragedy of slavery while demonstrating that no race is above savagery. One question he asks here is, to what ends savagery is used and when is it ever justified? Time has shown that perhaps no author of any color or gender did better on these topics and I’m not sure if any have since.

Another thing I love about Moby-Dick is Melville’s clear and complex fascination with (and love for?) whales, which permeates most of his writing about them (e.g. “The Grand Armada”Ch. 87, or “Does the Whale Diminish?” Ch. 105 and “The Dying Whale” Ch. 116), even aside from the purely cetological material and his one chapter of defending the “glory and honor of whaling,” which seems almost obligatory and understandably a bit defensive. Thus, the powerful and moving vividness of the Man and/vs. Nature theme.

To venture into deeper waters implicit in this theme, Melville may have chosen a white sperm whale as a symbol of what Edmund Burke called “the dynamic sublime,” and “in Ahab, Ishmael and others we see different human reactions to it,” according to a Harper’s magazine essay written after the BP oil spill, which treatened and may have harmed, among many other creatures, the endangered sperm whale, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“Modern man of power fears the whale, feels threatened by it, and is obsessed with his destruction. Modern man is driven by the desire to dominate his environment and chafes at those aspects of the world cannot control…The vision of Melville’s narration, however, appreciates the beauty and majesty of the forces of nature even as he reckons with their power and unpredictability.” 2

Unlike Ahab, Ishmael and Queequeg especially appreciate these forces because their daunting task to kill these gigantic, magnificent creatures, for the sake of the precious oil that lights lamps and street lights. This is part of what Ishmael, a fledgling whaler as the story begins, learns from Queequeg.

Only a master harpoonist like Queequeg knows truly what a great creature he is grappling with. In one extraordinary scene ( which no filmmaker has ever managed to stage) he literally dives into the water and crawls inside a fresh whale carcass to pull out a crew member who has accidentally fallen into a cavity cut into the whale. So he’s also a sort of Jonah turned hero.

All I can say is, dive in someday yourself– say, during a damp, drizzly November in your soul or a sun-blessed August afternoon on your shoulders.

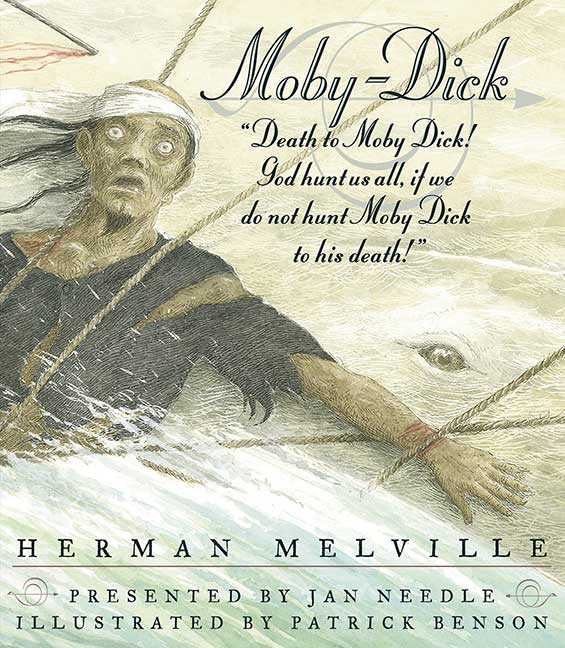

(For those who feel the need to get their feet wet first, or for a wonderful young person’s illustrated condensation of the book, I recommend Moby-Dick presented by Jan Needle and illustrated by Patrick Benson, Candlewick Press 2006. The book offers marvelously evocative artwork and a reasonably good condensation [down to 33 chapters] with explanatory chapter intros by Needle, who has been shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal and the Guardian children’s fiction prize. See book cover below)

In the novel, it is Fedallah, not Ahab, who gets accidentally entangled in the harpoon lines on Moby Dick.

Notes

1 Chapter 10 – “A Bosom Friend” Moby-Dick or, The Whale, Herman Melville, A Longman Critical Edition, Ed. John Bryant and Haskell Springer, Pearson Longman 2007, 62

*a good discussion of Fleece’s black dialect is in the”revision narrative” footnote (p 265) to the Longman Critical Edition, mentioned in my footnote above.

2 Melville — What the Whale Teaches Us — http://harpers.org/archive/2010/05/hbc-90006992