Edward S. Curtis and the Vanishing Race, through January 5. Museum of Wisconsin Art, 205 Veterans Ave., West Bend. 262-334-9638 wisconsinart.org

Edward S. Curtis began his rough-and-tumble, continent and mountain-traversing cultural odyssey by severely injuring himself. He nearly broke his back falling from a log while trying to pluck oysters from the mud to feed his fatherless family. Following the horrible winter of 1886-87, his father had moved them from Whitewater, Wisconsin to the Puget Sound area, but it was a failed man’s desperate act and he died soon afterwards.

While convalescing, 22-year-old Edward built his first crude camera with a lens his father left behind. His healing began a historic process of artistic and ethnographic importance. The transformational results, as this powerful exhibit demonstrates, would do extraordinary justice to the Native American race and helped initiate a cultural healing process that continues fitfully to this day.

The Museum of Wisconsin Art’s Edward S. Curtis and the Vanishing Race presents a magisterial sampling of the man’s unprecedented and unequaled 20-volume work of more than 2,000 photos and narrative, The North American Indian. As indigenous tribes disappeared into the ether, Curtis’ camera and growing obsession kept pace with the tragic decline — so that America might understand the meaning and value of the nation’s original people and culture, now displaced, eroded and often outlawed.

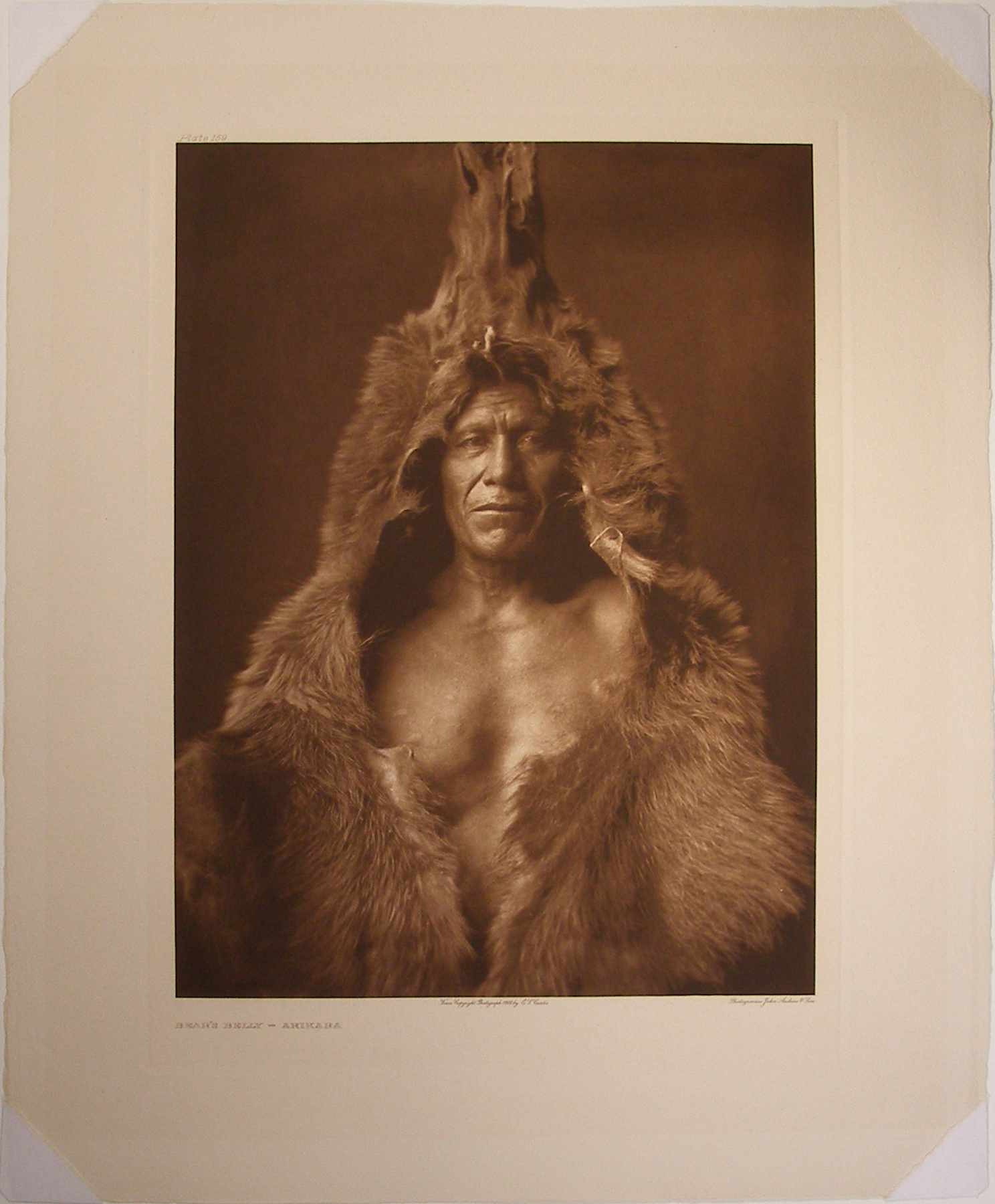

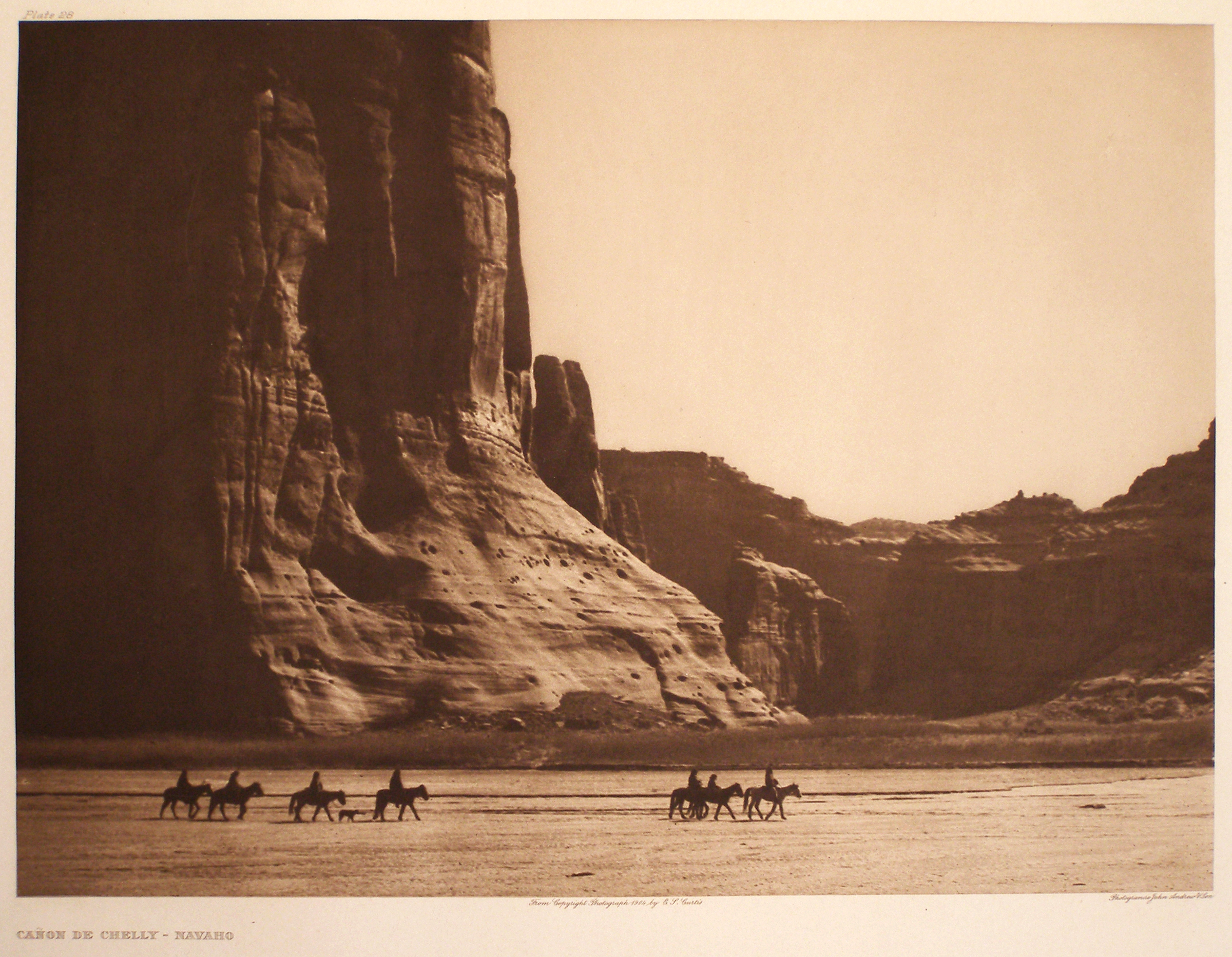

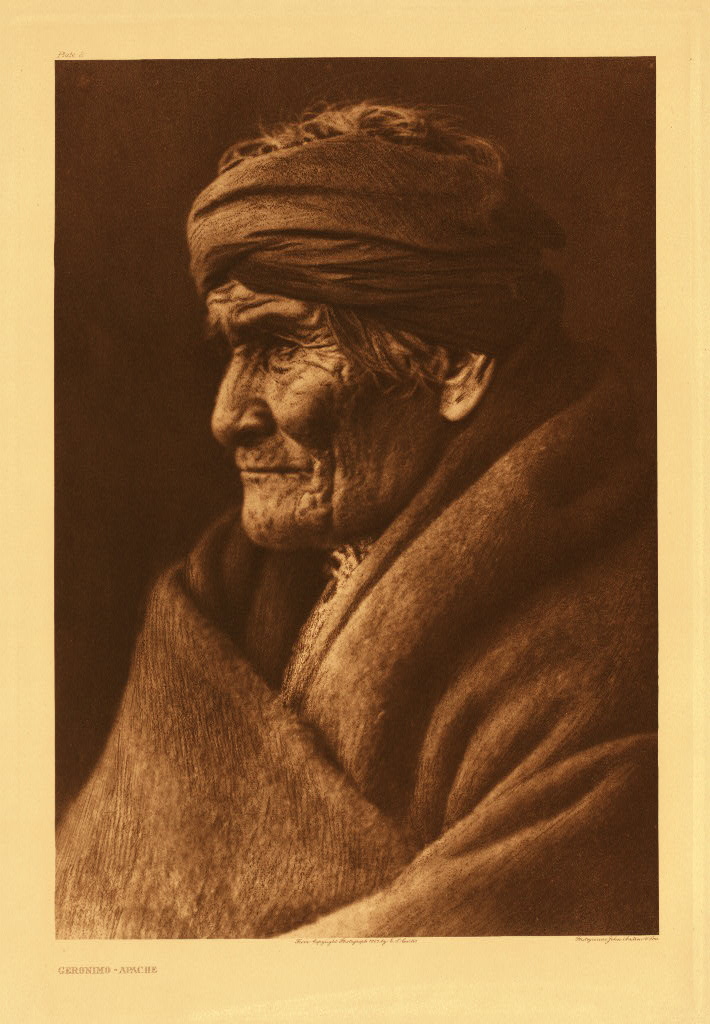

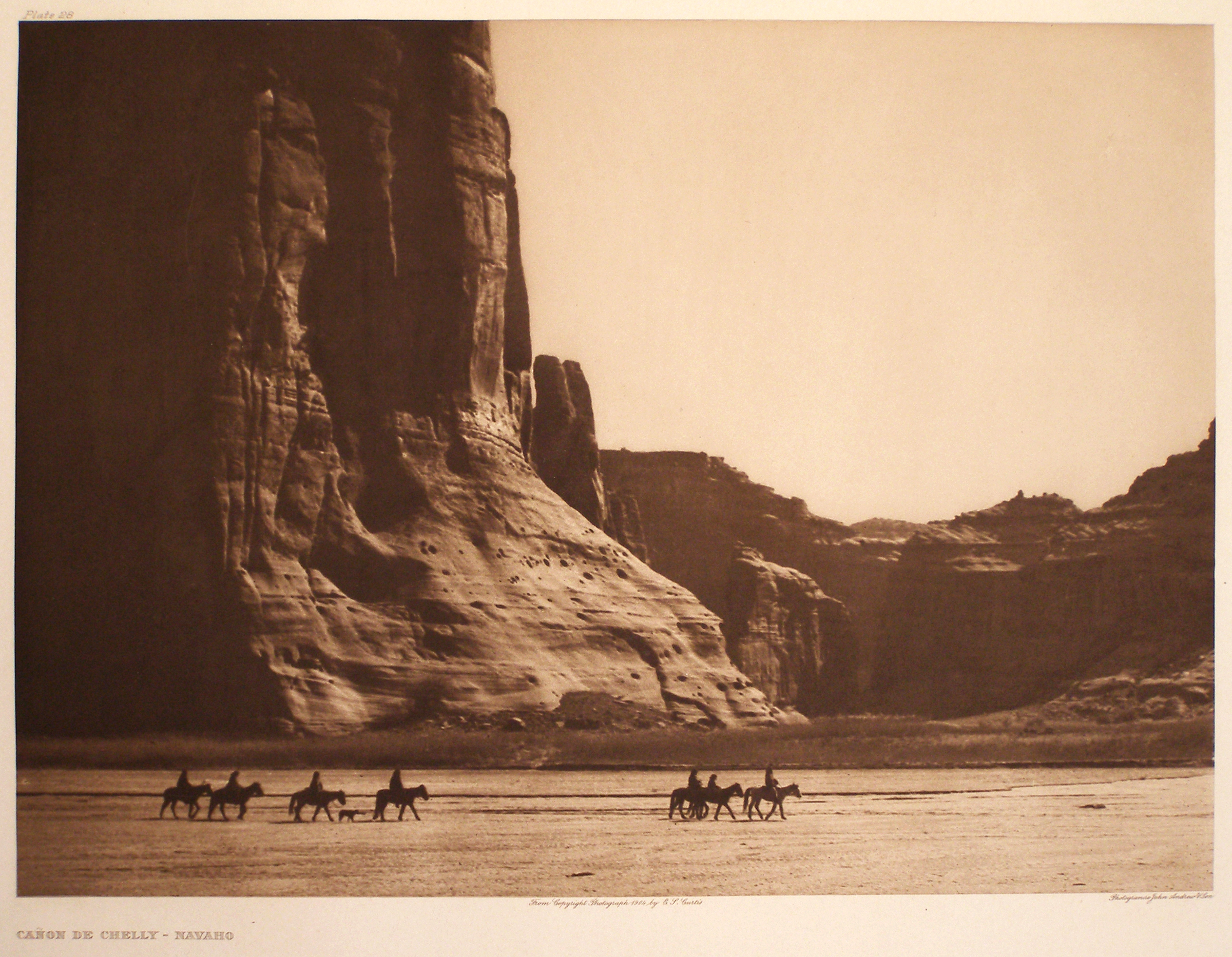

His sepia, noirish images radiate eloquent beauty that earned him the nickname “Shadow Catcher” from the Indians. Epic, brawny landscapes, such as Canon de Chelly—Navajo 1904 (above), influenced film director John Ford’s classic Westerns. Curtis’ shadows caught proud, suffering visages like Princess Angeline, (below) the last surviving child of Chief Seattle — in 1896 when Indians couldn’t legally live in the city named for her father. Her huddling scarf cradles the creased roadmap of a long, hard life. The photo brought Curtis fame he would parlay into the grand anthropological idea that would consume his life, family and marriage over the next 30 years.

While trekking up frigid Mount Rainier, the photographer saved the lives of two lost men. One was George Bird Grinnell, founder of the Audubon Society, and the foremost expert on Plains Indians. The grateful scholar would provide Curtis with access that would inflame the photographer’s imagination, insight and vision. Grinnell was impressed by the young man’s amateur anthropology, as Curtis collected bits of mythology and tribal narrative while taking pictures.

Grinnell had known General George Custer and he knew President Teddy Roosevelt. The scholarly man Indians had nicknamed “Bird” opened a wide aperture. Opportunity flooded in like a door thrown wide open. The Shadow Catcher walked right into the light. It helped that he was tall, handsome and charismatic. He would finance his improbable quest by gaining support and friendship of Roosevelt and art-loving banker J.P. Morgan, and by virtually never paying himself. Grinnell helped Curtis gradually win the native people’s trust, to allow his camera to explore the depths of their fading existence while retaining respect for it, says Graeme Reid, WMA director of collections.

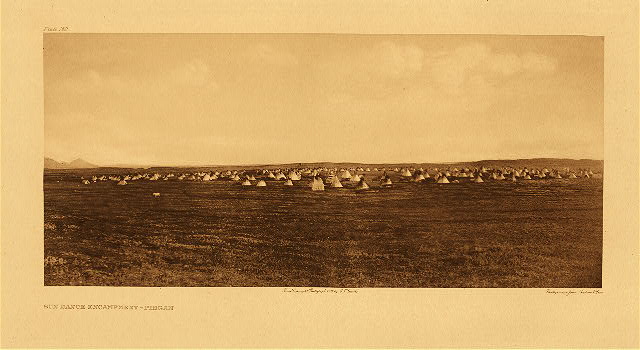

One delicately voyeuristic image reveals a large gathering of tipis for the sacred Piegan sun dance. The US government had outlawed the ritual as “an immoral dance,” an official act at that clearly violated First Amendment religious freedom rights, asserts Timothy Egan* in his fascinating 2012 Curtis biography, Short Nights Of The Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life And Immortal Photographs Of Edward Curtis. The photographer described the five-day dance as “wild, terrifying, elaborately mystifying. I was intensely affected.” 1 The ritual does involve a rather theatrical symbolic act of bloodletting by a participating dancer. *

Canada outlawed the Indian’s most honorable tradition — the potlatch –as “barbaric.” In this ritual, a person would give away his or her earthly possessions to others, paying it forward, in good faith the gift would be returned, with interest. 2

And in fact, Curtis — still struggling to finance his massive book project — would eventually produce what Egan describes as the first full-length documentary film in 1914 (with an audience –hungry title In The Land Of The Headhunters) depicting the life and culture of seafaring Kwakiutl tribe of the Northwest. Curtis and his film crew almost drowned during the project. Despite rave reviews and initial popularity, the film fell into obscurity, due to a dispute over distribution. Eight years later, the silent film Nanook of the North – A Story of Love and Life in the Actual Arctic gained credit as the first feature-length documentary. The film’s director Robert Flaherty had studied the Curtis movie frame by frame, and consulted with him on his methods.

Curtis’ ambitious project also included extensive field recordings on wax cylinders — 10,000 songs and vivid stories of Indian origins, hopes and devastation. One told of how, in the winter of 1883-84, one-fourth of the Piegan people starved to death as white hunters began slaughtering buffalo.

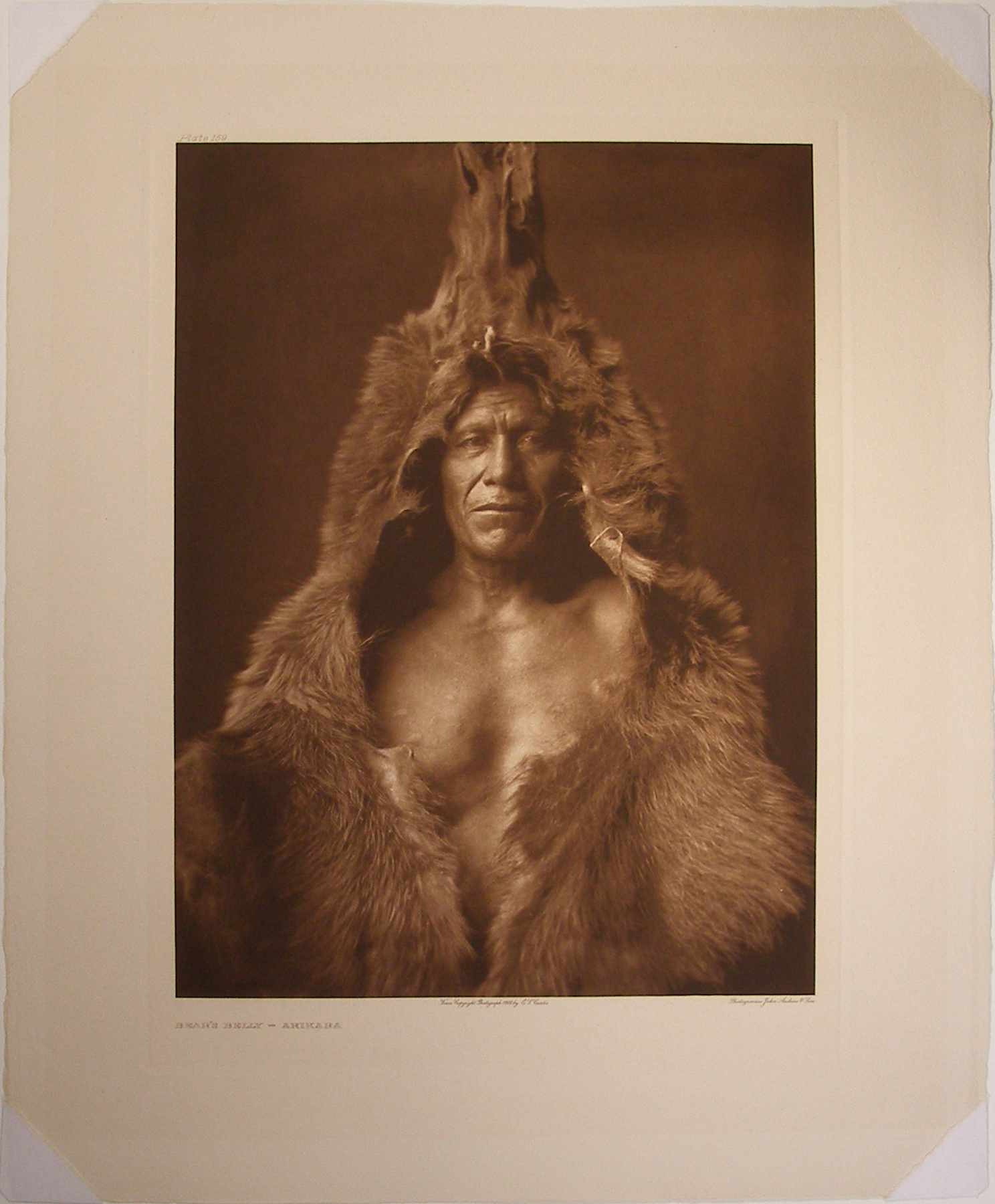

The 1926 religious ritual portrait Bear Bull-Blackfoot (top of post) captures the Indian’s symbiotic, intimate relationship with wildlife. Engulfing his body, the bearskin virtually reincarnates the mighty animal, and feels like a coffin for Bear Bull’s own passing. Look at him. His face and scarred chest, defiant and handsome, is humanity, infused with nature. It a condition virtually never achieved by Western man, since the Age of Reason.

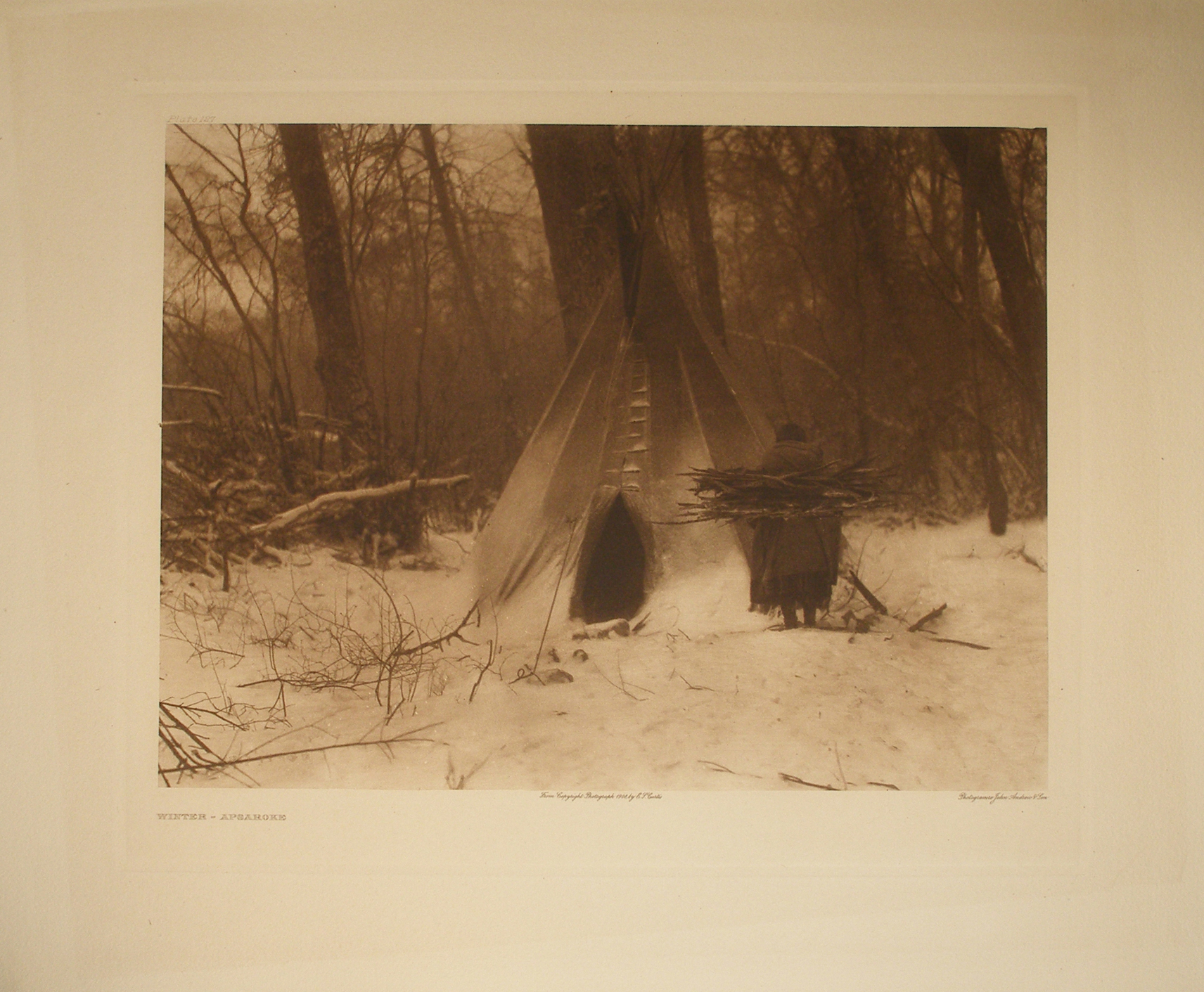

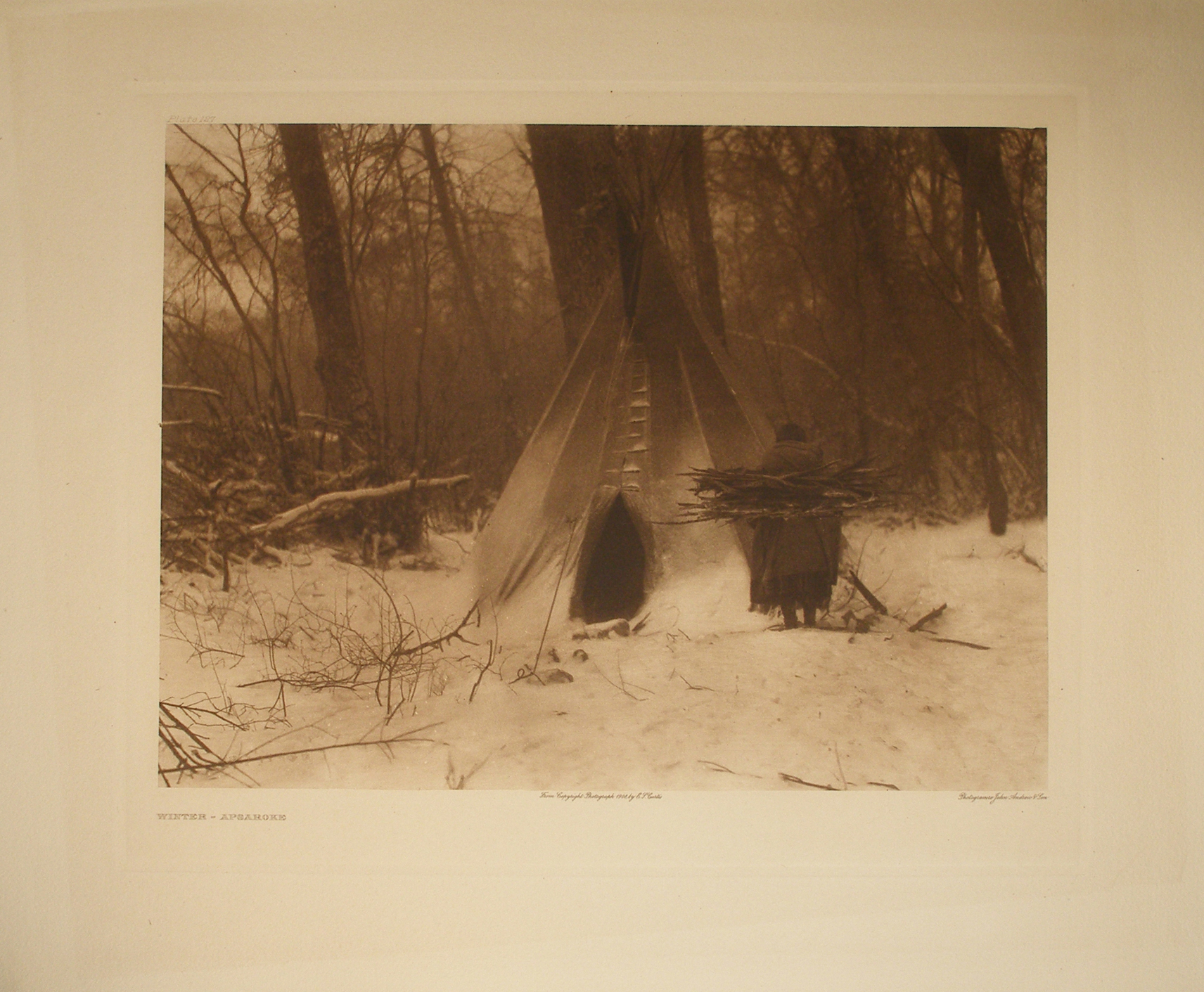

A superbly composed image, Winter – Apsaroke (below) crystallizes the harsh Plains winter of 1908 as a Crow woman, bent under a bundle of kindling, retreats to her tipi — partially encased in creeping, merciless ice. The tipi entrance intimates a fateful black hole. In that era, thousands of Indians, lacking white settlers’ immunities, died of pneumonia in winter and cholera in summer, and from other European-borne diseases like smallpox, scarlet, tuberculosis. 3

Such a trail-blazing and astonishingly ambitious project could hardly avoid controversy or criticism. A number of Curtis’ photographs documented sacred rituals and traditions that were never meant to be seen by the uninitiated.

And his historical research — assisted by Crow scouts who witnessed the battle — revealed a dramatically revised story of Gen. George Custer and his famous defeat at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. The glory-thirsty general reportedly stopped, waited and watched as his colleague General Marcus Reno and his troops battled, while heavily outmanned by the much larger Sioux forces, according to the scouts.

“Curtis estimated (Custer) was close enough ‘that it was almost within hailing distance’ … Custer dismounted and took in the carnage while sitting on the grass, as if being entertained by blood theater, the Indians claimed. White Man Runs Him (an aptly named scout) said he begged Custer intercede, scolding him for letting soldiers die. “No,” the commander replied. “Let them fight. There will be plenty of fighting left for us to do.” 4

Custer and his men paid the ultimate price for his arrogance and vanity. Curtis eventually refrained from publishing his Custer revisionism in The North American Indian, save one muted comment: “Custer made no attack, the whole movement being a retreat,” in Vol. III. Yet after years of keeping a pledge to not address politically and socially troubling issues in his texts, Curtis eventually railed against government agents and missionaries, and the long litany of racial injustices he had uncovered and witnessed.

Curtis has also been accused of romanticizing the Indian. On one occasion, he had an assistant erase an alarm clock from an image of an Indian’s sleeping quarters. He rarely ever tampered with the documentary truth of the camera’s eye, although he became a sophisticated and innovative artist at enhancing his photos in the studio.

Mostly, these photos feel honest, unflinching, and far-reaching. As Egan writes: “Curtis saw a moment from a time before any white man had looked upon these shores. He saw a person in nature, one in the same mind, as they belonged.”

Clara Curtis divorced her husband in 1919, charging adultery and cruelty — to banner headlines in Seattle. Curtis denied any infidelity but she won their home and his studio in the settlement. Clara also began visiting the studio and picking fights with their daughter Beth, who was now running it. Clara accused Beth of funneling money to her father. With his main benefactors dead, Curtis was actually living like a hobo, closer to the sky and to the spirit of Native Americans – though not by choice. He was still trying to complete his book series.

It’s amazing what he had accomplished; his formal education stopped in the sixth grade. But now he was middle-aged. He took a job doing promotional photos in Hollywood, from shooting Elmo Lincoln for a series of silent Tarzan movies to taking photographs for Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, in production. The guy from Whitewater never got a screen credit from DeMille.

“Curtis never thought of Hollywood as anything but a sad, single-business town full of hustlers,” Egan comments. Curtis was one of the great hustlers in American history, but not this kind.

Yet Hollywood would redeem itself in the form of one of its biggest stars, Robert Redford. He had a vision, for which he took the name of the profound Indian religious ritual — The Sundance Institute, which sustains a program to support Native American film makers, begat the independent and quintessentially American Sundance film production company and cable channel, all pursuing environmental integrity and creative experimentation.

Said Redford: “This place in the mountains, amid nature’s casualness toward death and birth, is the perfect host for the inspiration of ideas: harsh at times, life threatening in its winters of destruction, but tender in attention to the details of every petal of every wildflower resurrected in the spring. Nature and creativity obey the same laws, to the same end: life.” 5

That sounds like something Curtis might’ve said. Culture currents can run deep and far.

Edward Curtis died in 1952. He remains relatively neglected by art historians, even those who specialize in American art. The North American Indian also languished in obscurity for decades, until it was rediscovered in the 1970s.

This is the first exhibit of Curtis’ work in his home state in a decade. The impressive, stylish and completely new art museum, dedicated to Wisconsin art and artists, is doing a special service with this show and a concurrent exhibit by Madison-based Ho-chunk artist Tom Jones.

“With the opening of our new building this spring, we made a commitment to feature on a more regular basis, some of Wisconsin’s oldest art—that of Native American tribes,” says Laurie Winters, MOWA Executive Director/CEO. “In our inaugural year at the new location, visitors will actually be able to see this promise carry through.”

___________________________________________

All photographs by Edward L. Curtis, courtesy of Collection of Dubuque Museum of Art, Dubuque, Iowa. Gift of Dubuque Cultural Preservation Committee, an Iowa general partnership consisting of Dr. Darryl K. Mozena, Jeffrey P. Mozena, Mark Falb, Timothy J. Conlon, and Dr. Randy Lengeling.

*Egan won the Chautauqua Prize for his Curtis biography. He also won a Pulitzer Prize in 2001 for National Reporting for contributing to The New York Times series, How Race Is Lived In America . In 2006, he won The National Book Award For The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived The Great American Dustbowl.

1 Timothy Egan, Short Nights Of The Shadow Catcher The Epic Life And Immortal Photographs Of Edward Curtis. Mariner Books, 2013, 49

2. Ibid. 32

3. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_American_disease_and_epidemics

4. Egan, 165

5.http://www.sundanceresort.com/about/story.html

Related events:

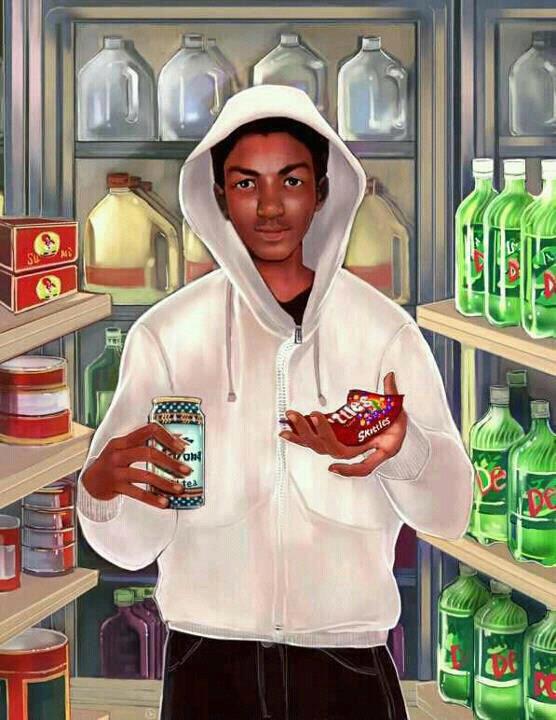

- Madison-based Ho-Chunk artist and photographer Tom Jones will be featured in MOWA’s State Gallery in I am an Indian First and an Artist Second. The show includes two bodies of work. The first uses plastic Indian figurines abstractly as a metaphor for what Jones perceives as a form of identity genocide. The second body of work, The North American Landscape, is a contemporary response to the photogravures of Curtis. The Jones show will open September 6 and run through December 1, with an opening reception 5 to 8 p.m. on Friday, September 6.

- Kelly Kirshtner, PhD. University of Wisconsin — Milwaukee, will give a talk on Edward Curtis and his influences on cinema at 6:30 p.m. Thursday, September 26 at MOWA.

All programs and events are free for MOWA members (the $12 museum entry fee includes membership) and no pre-registration is required.

A version of this article was originally published in the Aug. 21, 2013 edition of The Shepherd Express.

Like this:

Like Loading...

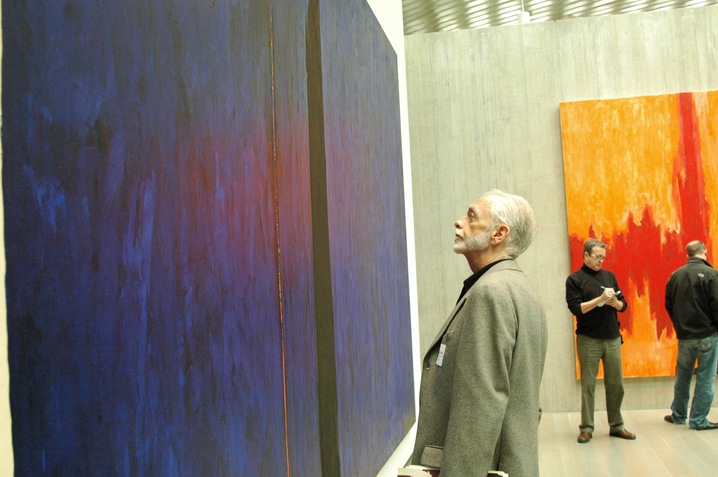

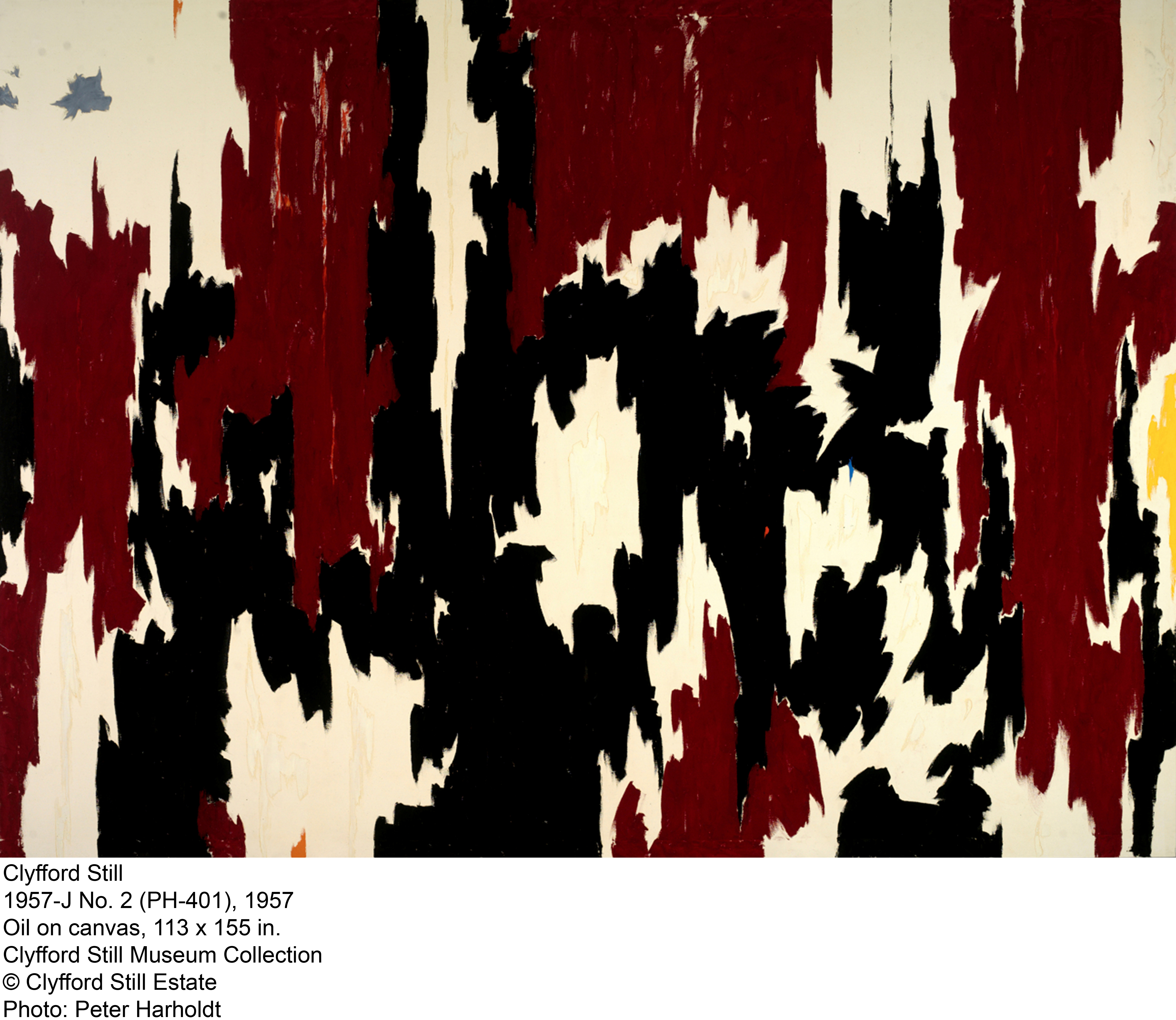

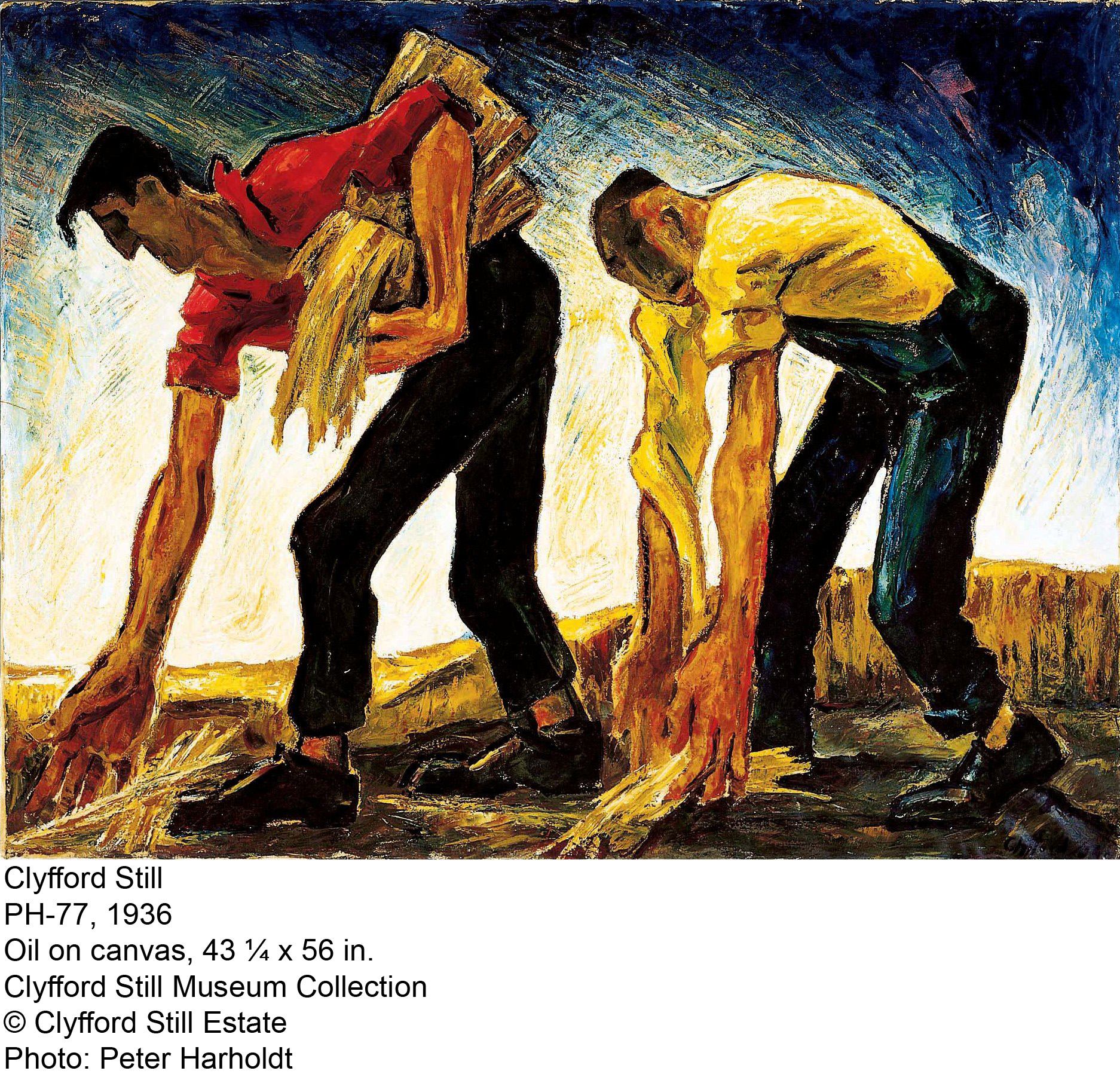

A visitor contemplates a painting in the Clyfford Still Museum. Photo by Rebecca Jacobson/PBS newshour

A visitor contemplates a painting in the Clyfford Still Museum. Photo by Rebecca Jacobson/PBS newshour

A Westerly Cultural Travel Journal, Vol. 2

A Westerly Cultural Travel Journal, Vol. 2

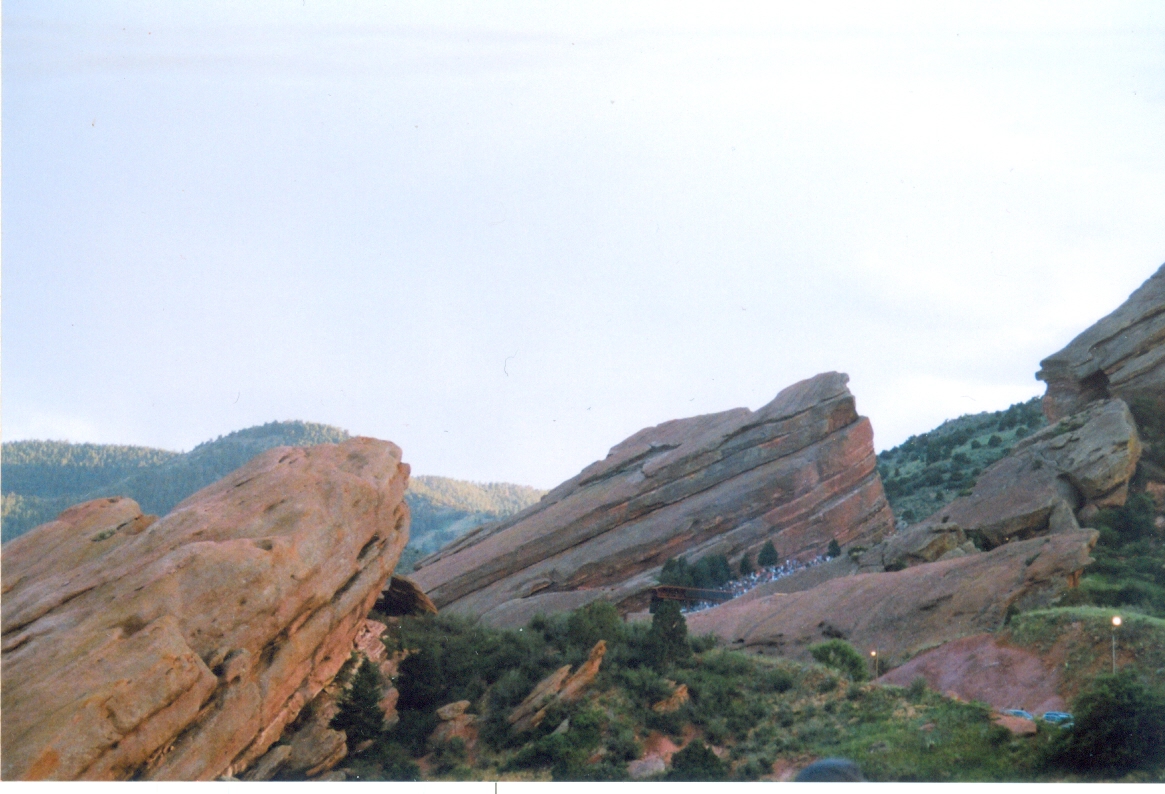

Susan Tedeschi at Red Rocks. Photos courtesy CBS Denver

Susan Tedeschi at Red Rocks. Photos courtesy CBS Denver

This painting depicts the Civil War’s fiery and crucial Mississippi River battle for Vicksburg. courtesy of ashvilleoralhistoryproject.com

This painting depicts the Civil War’s fiery and crucial Mississippi River battle for Vicksburg. courtesy of ashvilleoralhistoryproject.com