The panoramic, rugged and historically tragic Donner Pass in western Nevada, along today’s Interstate 80. Courtesy panoramia.com. *

A Westerly Cultural Travel Journal

If the Mississippi River is America’s main artery and lifeblood, I consider the plains and mountain states this country’s backbone. I say this as a lifelong Midwesterner, believing my native grounds as America’s heartland, as do many others. To complete the metaphor, perhaps the East is the nation’s august head and shoulders.

My traveling partner Ann Peterson and I set out in late October to traverse the vast, mighty backbone once, in a road odyssey from Milwaukee to San Francisco and back, which totaled close to 4,500 miles. Some friends had scoffed at us doing the car road trip.

We aimed to get to San Francisco in three days. Our first and most challenging goal was to drive from Milwaukee to Boulder — or 1,062 miles — in the first day. Our halfway-there host, my sister-in-law Kris Verdin, had written that it was “insane, but doable.” But the West Bend WI native hadn’t done that since she and her husband Jim had been young.

Ann and I are now in our early 60s. Packed up, we finally got past the freeway over-development in Wauwatosa and Brookfield that is further ravaging our state’s ecological balance and livability. Westbound and wide-open ahead, my 2010 Toyota Corolla growled as I gunned it. We were off.

It was Tuesday and we wanted to reach San Francisco by Thursday night, so we’d have time to decompress and be ready for Friday’s first of two consecutive nights of the all-star SFJAZZ Collective. They would perform the music of the great saxophonist-composer Joe Henderson and their own originals at the SFJAZZ Center, the only building in America designed specifically for jazz performances. The performances would be recorded for a future CD. (The band’s co-founder and lead alto sax player Miguel Zenon is the subject of the cover story of the latest Down Beat magazine.)

It would also my re-union with Divina Infusino, my former colleague at The Milwaukee Journal in the 1980s, when she covered rock and pop music and I covered various music and visual art, with a jazz specialty.

We ended up not exactly following the Trip-tik route that Ann had taken pains to gather and print out. Instead we forged through Southwest Wisconsin’s “God’s country,” which blazed with a fall color panorama, even a week or so past peak. We would soon encounter more spectacular mountainous contours, but there’s no greater undulating autumn beauty than in the sinuous hills of southeastern Wisconsin. The colors burn into the eyes, a kaleidoscope of crimson, gold and orange with wave-like, wind-swept textures. Even prodigal son Kareem Abdul-Jabbar marvels over Wisconsin’s fall beauty in the recent Zucker brothers TV commercial for Travel Wisconsin. “I can’t believe I ever left this place!” Jabbar exclaims, reprising his pilot role in the Zuckers’ hit movie Airplane! The all-time NBA scoring leader had also lobbied for the Bucks coaching position not long ago.

But we were leaving for two weeks and needed to make good time, to “ball the jack,” as Jack Kerouac once called it, but with a purpose (“No sooner were we out of town than Eddie started to ball that jack ninety miles an hour out of sheer exuberance.” –Jack Kerouac) 1. I also hit 90 miles an hour, but not until we reached the flatland straightaways of Nebraska, and my Corolla smoothly zoomed to 98 at one naughty spurt, which I hardly noticed till I glanced at the speedometer.

I wanted to reach Boulder by 2 a.m. (the hour of the body’s deepest sleep alpha waves) even though a detour and a slight disagreement on the route kept Ann and I from escaping Milwaukee by 9 a.m. So I was balling that jack out of sheer determination.

Iowa provided striking distractions at several of its Interstate rest stops, including Iowa sculptor Tom Stancliffe’s handsome, witty brushed stainless steel and bronze sculpture Harvest, columns arranged as a row crop (below). Among the depicted resources is a book, a reminder that this farming state is also home to the world-renowned Iowa Writer’s Workshop which has produced 17 Pulitzer Prize winners (most recently Paul Harding in 2010) and four recent U.S. Poets Laureate.  Ann Peterson posed with “”Harvest,” Tom Stancliffe’s 1999 sculptural rendering of Iowa’s important resources and icons, including corn, sunflowers, acorns, fish, hogs and books (detail below). It’s at the Cedar County Area Rest Stop and Welcome Center on I-80. Photo by Kevin Lynch

Ann Peterson posed with “”Harvest,” Tom Stancliffe’s 1999 sculptural rendering of Iowa’s important resources and icons, including corn, sunflowers, acorns, fish, hogs and books (detail below). It’s at the Cedar County Area Rest Stop and Welcome Center on I-80. Photo by Kevin Lynch  Photo by KL

Photo by KL  Photo by Ann K. Peterson

Photo by Ann K. Peterson

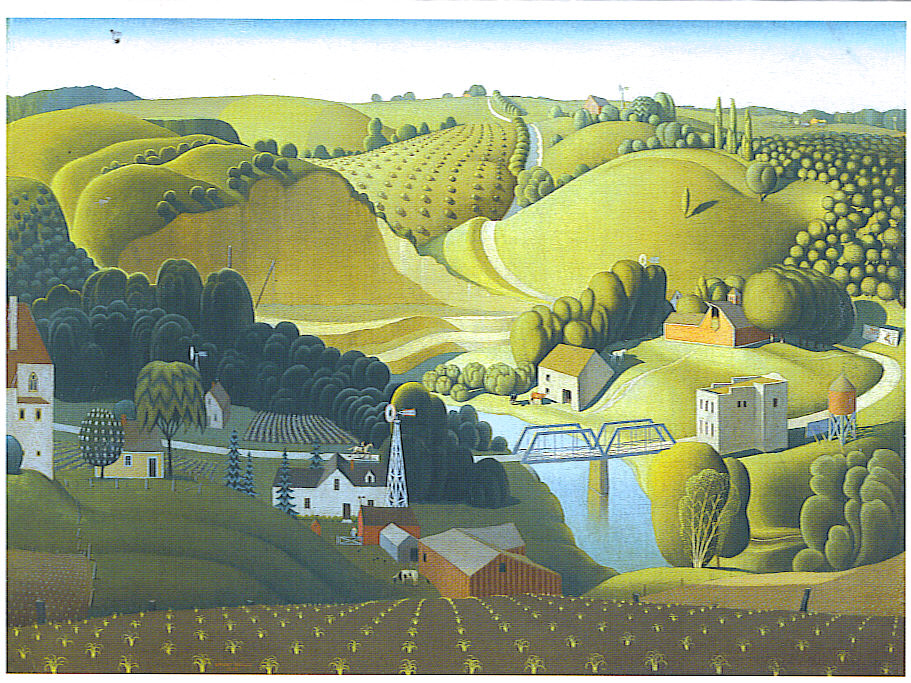

At the top of the tower at left (above), Stancliffe interpreted in bronze Grant Wood’s famously bounteous 1930 oil paint landscape Stone City, Iowa (below, courtesy newyorkarts.net).  At another point in Iowa we looked dumbfounded –at the longest truck rig I’ve ever seen, parked at a rest stop. The endlessly long white shape mystified us. Was it a portion for a gravity-defying Santiago Calatrava building? A wing for a giant stealth bomber? Further down the Interstate the wind blew the mystery away when — at another rest stop — we suddenly saw the identical form standing at proud, erect attention, seemingly scraping the sun. In a huge concrete and steel base stood a wind turbine propeller blade.

At another point in Iowa we looked dumbfounded –at the longest truck rig I’ve ever seen, parked at a rest stop. The endlessly long white shape mystified us. Was it a portion for a gravity-defying Santiago Calatrava building? A wing for a giant stealth bomber? Further down the Interstate the wind blew the mystery away when — at another rest stop — we suddenly saw the identical form standing at proud, erect attention, seemingly scraping the sun. In a huge concrete and steel base stood a wind turbine propeller blade.

A gift of the Mid-American Energy Company and Siemens Energy, the blade is 148 feet tall and weighs 23,098 lbs.

Photos by KL

Photos by KL

Such mechanisms, of course, are a key to the burgeoning renewable energy movement. And word has it, engineers are now working on creating turbines that are less hazardous to flying birds.

Yes, the trip had blown pretty cool since escaping Milwaukee. However at about 150 miles, I noticed a light on my dashboard signaling “MAINT REQD”

“Oh shit!” I muttered. I had dutifully taken the car into the Toyota shop right before we left –the mechanic had pronounced it ready to roll to the coast and back. Ann proved the cooler head, figuring the signal had kicked in because I had passed the 3,000 mile mark since my last oil change. She assured me that Click and Clack of Car Talk on NPR say that you only need to change oil after about 5,000 miles. They are the Holy Trinity-minus-one of car advice, so I felt blessed by the cosmos.

Sure enough, when we reached Nebraska and night fell, a vast and vivid canopy of the night hovered overhead — “billions and billions and billions” of stars, as the late astronomer Carl Sagan might’ve put it. I was really glad that — after my last car was totaled by a hit-and-run driver — I bought a car with a sunroof. I got a little high on the real, infinite thing right over my head as Ann drove.

In Lincoln, Nebraska we stopped for hearty salads at Wendy’s and for a quicker peek at King Kong, a small regional burger-Phillie steak-gyro chain, across the road.  King Kong stands atop the sign for the fast food joint in Lincoln, NE named for him. The sign was too hot in contrast for this night photo to make out the words “KING KONG.” Photo by KL

King Kong stands atop the sign for the fast food joint in Lincoln, NE named for him. The sign was too hot in contrast for this night photo to make out the words “KING KONG.” Photo by KL

The joint boasted a delightful King Kong motif, with hairy gorilla dolls hanging from the ceiling, and big, blazing posters from the original 1933 movie with Faye Wray and Robert Armstrong and, of course, Kong!  The French were very big on the original “King Kong,” as this inspired poster by a French artist indicates. Courtesy highlight Hollywood.com

The French were very big on the original “King Kong,” as this inspired poster by a French artist indicates. Courtesy highlight Hollywood.com  Here’s Fay Wray, the “beauty (who) killed the beast.” Once, when I saw “King Kong” in a movie theater, Ms. Wray came on screen and a lecherous guy in front of me muttered to his companion, “What a dish.” Courtesy bobbyriverstv.blogspot.com

Here’s Fay Wray, the “beauty (who) killed the beast.” Once, when I saw “King Kong” in a movie theater, Ms. Wray came on screen and a lecherous guy in front of me muttered to his companion, “What a dish.” Courtesy bobbyriverstv.blogspot.com

However, I was disappointed to find the burger shop didn’t have the original King Kong on constant replay on their TV screen.  Kong fends off the airplanes atop the Empire State building, as epic a battle as the movies has ever given us. Courtesy highlight Hollywood.com

Kong fends off the airplanes atop the Empire State building, as epic a battle as the movies has ever given us. Courtesy highlight Hollywood.com

(Instead they had the World Series on — we’d get plenty of World Series mania when we reached San Francisco) “I’ve been here for years and you’re the first person who has asked about the movie,” the Kong manager said. “Good idea. I’ll have to suggest that to the owner.”

I hope to return to King Kong someday and munch a Kong burger as fictional film-maker Carl Denham sagely intones to the mustachioed NYPD officer, “Oh no, it wasn’t the airplanes. It was beauty that killed the beast,” in glorious black and white. And yes, that Empire State Building death battle helped cement the East as America’s head and shoulders. With Kong’s blood streaming onto the Manhattan street, Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong in tuxedo, left), delivers his famous closing lines to the original “King Kong” (“Oh no,…”) courtesy bobbyriverstv.blogspot.com

With Kong’s blood streaming onto the Manhattan street, Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong in tuxedo, left), delivers his famous closing lines to the original “King Kong” (“Oh no,…”) courtesy bobbyriverstv.blogspot.com

I did my best nasal impersonation of Denham’s closing lines for Ann and explained to her that my old Marquette High poster club buddies and I act out the complete death scene of Kong with full theatrics and sound effects. We would do a command performance the next time the three of us are together. Wisely, she’s not holding her breath.

My sister-in-law Kris called by cell shortly after we had left Lincoln, and estimated we’d get to her house in Boulder “by two-ish.” Her watch dog Ella would surely wake her, but that’s OK, Kris assured.

This only steeled my determination to get there earlier. We drove late into the night and what kept us awake was the CD player: Richard Thompson’s latest CD Acoustic Classics, the Christine Jensen Jazz Orchestra’s Habitat, Wilhelm Kempff’s classic recordings of Beethoven’s “Pathetique,” “Moonlight,” “Waldstein” and “Apassionata” piano sonatas and country singer Patty Loveless’ Mountain Soul (my tastes are nothing if not eclectic).  Patty Loveless’s rootsy bluegrass CD “Mountain Soul” courtesy of amazon.com

Patty Loveless’s rootsy bluegrass CD “Mountain Soul” courtesy of amazon.com

Then we settled in to listen to Lorrie Moore’s latest collection of short stories Bark on CD. The author reads the stories in her warm, breathy, slightly phlegmatic voice, with her New York accent still curving certain words, despite several decades of living in the Midwest as, until recently, a chaired professor of creative writing at the UW-Madison. Moore’s tersely adroit reading of her own story helped us plow through the darkness.

The opening tale “Debarking” told about about Ira, a hapless divorced father of a teenage daughter sticking his toe into the dating scene after years of marriage. He falls for a divorcee named Zora who pierces his heart as surely as might Zorro (Moore never misses a chance for pointed, symbolic wordplay). But Zora’s emotional lance is actually embedded in her adolescent son Bruno, to quite Oedipal depths, and the lad treats Ira like a bothersome stray dog.

The story is set during the American bombing of Baghdad in the Iraq War. Ira and Zora begin a wobbly, sometimes tender interplay of emotional “debarking.” It doesn’t end well. Zora finally informs Ira she’s been on anti-depressants and really misses Bruno, who’s merely at school for the day.

“I’ll call you tomorrow,” he said, though he wouldn’t. He backed out of her driveway…Was he too old fashioned?…He headed to a dank, noisy dive called Sparky’s where he went to just after Marilyn left him… All his tenpenny miseries and chicken-shit joys would lead him once again to Sparky’s. Those half-dozen times he had run into Marilyn…he had felt like a dog seeing his owner…But at Sparky’s he knew he was safe from unexpected encounters with Marilyn …

Ira ordered bourbon straight up. “He let the sharp buttery elixir of the bourbon warm his mouth then swallowed its neat, sweet heat …over and over, ordering drink after drink …until he was lit to the gills.”

Ira made a rambling toast: “Happy Easter…The dead shall rise, the dead are risen, the damages will be mitigated. The Messiah is back among us, squeezing the flesh…Okay, God looked away for a second to look at ‘I Love Lucy’ reruns, but he is back now…He, watching over Israel, slumbers not, nor sleeps.”

“Somebody slap that guy,” said the man in the blue shirt at the end.  Hard-working nurse practitioner Ann slumbered however, there at the story’s end, the passenger seat tilted back, her head against the plush bed pillow she’d brought along.

Hard-working nurse practitioner Ann slumbered however, there at the story’s end, the passenger seat tilted back, her head against the plush bed pillow she’d brought along.

I pressed ahead. I’ve never driven that late into the night — midnight, 1 a.m. — without fatiguing. I hung on hard to the wheel and kept leaning forward. It helped that the Corolla ran smoothly at 80 MPH-plus, so my body didn’t endure a shaking car but still felt its energy.

When we reached the Nebraska/Colorado border, night prevented the view I got last summer of the striking contrast in landscapes right there. You enter Colorado and the somewhat green expanses of Nebraska suddenly transform into desolate desert, with almost nothing but sand, sagebrush and tumbling tumbleweeds. Nebraska apparently cornered the market on viable farmland when their state border was demarcated in 1867, nine years before Colorado.

***

We finally reached Denver, then jumped on a northwest turnpike to Boulder. Scorning my trusty Rand McNally atlas, I went on my memory of Boulder from last summer when I drove out there for a Tedeschi-Trucks Band concert at the magnificent Red Rocks Ampitheater. So it took a bit more meandering but we finally found Snowmass Ct. and rang Kris Verdin’s doorbell at 1:45 a.m. mountain time. Milwaukee-to-Boulder in one day. We’d beaten Kris’s arrival estimation, which had also been our target time.

Sure enough, Ella the watch dog greeted us at the door with “ROWF! ROWF!” I asked Ella if I could quote her, and so I have. My trusty Corolla cooled its jets, with narry a blip on the trip (nor for the rest of Kevin and Ann’s Excellent Adventure). With Kris’s ready graciousness, we crashed quickly in her guest room.

The next morning she’d left for work, and the Verdins’ gleaming, high-tech coffee-maker threw a hissy fit (I failed to follow Kris’s directions). So we stopped at a Starbuck’s and hit the road as quickly as we could, again chasing the West’s golden sun which glared at us imperiously as it slowly settled, like a queen in gilded robes, onto her throne — the mighty mountains on the horizon.

We had the popular Road Food app, a guide to interesting restaurants on the American highway, but all it listed in Cheyenne, Wyoming, was a bison burger farm-restaurant that actually gives you a ride onto the ranch where you pick out a majestic creature to slaughter. They proceed to shoot, chop and grind your fresh burger. Such brutal, culinary intimacy appealed to neither of us.

So gas-stop locals recommended The Tortilla Factory, an unassuming Mexican joint with a backside parking lot entrance. Swollen, steamy enchiladas and gloppy refried beans were just the ticket. With renewed gas exhaust — from within and without — we pressed ahead.

Here’s where the roads began to really cut into mountainsides, and creep steadily around their massive shoulders. As we climbed the steep highway we passed plenty of groaning, heaving semis. In my mid 20s to age 30, The Grand Tetons in northwest Wyoming were almost my yearly destination for mountain climbing. I had never visited southern Wyoming and now the trip along Interstate 80 proved how stunningly picturesque the state also is down here. The photos below only hint at their presence.

The massive craggy formations come alive with an almost breathing aura as the sun falls lower into the west and the shadows the rocks cast stretch, long and ominous. The combination of ripped-rock formations and lower vegetation-covered mountains made for a wonderful textural Yin-Yang.

Wyoming on Interstate 80. Photos by KL

Wyoming on Interstate 80. Photos by KL

On increasingly steep and winding interstate stretches, we began seeing signs warning against trucks tipping over on treacherous turns and the emergency braking lanes for runaway trucks. Considering the intense pressure truckers feel to drive as far and as fast as possible, it’s hard to imagine hauling a loaded semi through many of these precipitous highway curves and drop-offs at speeds of up to 60 miles an hour, with the risk of a run-away rig hurtling much faster.  A trucker balls the jack through mountainous Wyoming highways. Photo by KL

A trucker balls the jack through mountainous Wyoming highways. Photo by KL

But they do it, and at many stretches of our trip we saw more large trucks on the road than automobiles. It underscores how important it is for America to keep its infrastructure in tip-top shape, especially in today’s globally competitive world.  The treacherous Highway 5 in B.C., also called the Coquihalla, has claimed many victims. Courtest driving. ca

The treacherous Highway 5 in B.C., also called the Coquihalla, has claimed many victims. Courtest driving. ca

That night we made it from Boulder to Salt Lake City and by then driver Ann was cross-eyed and gassed. I realized we had nearly 200 miles to our theoretical destination in Nevada, so we decided to call it a night. I asked a hostess at Olive Garden for directions to a nearby motel and she directed me to the downtown Main Street. We gamely followed her directions and found State Street, with the Utah state capital building visible at the far end.

However, at this end of the street things seemed hardly stately. It smelled like the city’s red-light district. We spied a few hookers tottering around on spike heels and scant clothing in the chilly night.

Ann shuddered as I slowly drove past motel after motel. How bad could it be? I wondered aloud. This is the home of the holy-roller Mormons! We finally pulled into one motel parking lot that seemed momentarily civil, and immediately several men opened motel doors to peer at us in unison, like an over-rehearsed scene in an X-rated movie. “CUT! One at a time, you idiots! Not so eager for the beaver!” the director with the hairy chest and gold chains would shout from his megaphone.

Suddenly I felt like a greasy pimp and Ann felt like Linda Lovelace — long before her hard-earned Deep Throat experience.

“Let’s get out of here,” she shivered, “This is really creepy!” We meandered through the night till we found a Motel 6 on the outskirts of town, and hard pillows never felt so good. At least they were clean, despite the cigarette burn hole in the bed spread.  Suddenly a slightly tattered Motel 6 seemed like Nirvana. Courtesy blog.trekeffect.com.

Suddenly a slightly tattered Motel 6 seemed like Nirvana. Courtesy blog.trekeffect.com.

After an omelette breakfast at a Denny’s teeming with policemen and guerrilla-garbed soldiers, we took aim for San Francisco. I hit my highest speed crossing the seemingly endless straightaway portion of US 80 that bisects the great Salt Lake Desert. But hey, world records for highest land speeds are regularly broken here on the salt flats.

The desert is an odd phenomenon: It’s a shallow lake 81 miles wide — over a bed of sand a thin layer of salt hovers, covered by a glaze of water. During Jedediah Smith’s 1826-7 expedition, Robert Evans died in this desert; and in the 1840s, westward emigrants used the Hastings Cutoff through endless the desert to reduce the distance to California. 2 Shadowing the ancient trail of explorers would lead us to a daunting historical discovery.

Past the salt lake, I grew curious about the river following the now-twisting highway. So we Googled it on Ann’s smart phone and discovered it was the Truckee River. We soon reached the cavernous Donner Pass (formerly the Truckee Pass, see photo at the top of this travelogue). I began reading a bit about the Donner Party, and again thanked the car gods for a trusty Toyota.

The Donner name hearkened to over a 150 years ago when people tried to traverse this brawny and unforgiving beauty before motor vehicles were invented. The Donner Party were pioneers who set out for California in a wagon train, from Springfield, Illinois. The journey west usually took between five and six months, but the Donner Party fatefully followed the newly named Hastings Cutoff, which crossed Utah‘s Wasatch Mountains and the Great Salt Lake Desert. The rugged terrain, and difficulties encountered while traveling along the Humboldt River in present-day Nevada, resulted in the loss of many cattle and wagons, and splits within the group.

By the beginning of November 1846 the emigrants had reached the Sierra Nevada. You can see by the panoramic view of present-day Donner Pass (see link at bottom of post), the sort of head-swelling natural beauty that filled their senses and lured them further — into equally treacherous terrain. They became trapped by an early, heavy snowfall near Truckee (now Donner) Lake, engulfed by mountains and brutal winds.  An artist’s rendering of the The Donner Party’s hardships. Courtesy corvallistoday.com.

An artist’s rendering of the The Donner Party’s hardships. Courtesy corvallistoday.com.

Their food supplies ran extremely low, and in mid-December some of the group set out on foot to obtain help. Delayed by a series of mishaps, they spent the winter of 1846–47 snowbound in the Sierra Nevada. Some of the immigrants resorted to cannibalism to survive, eating those who had succumbed to starvation and sickness. Here are entries from the diary kept by party member Patrick Breen:

“… Peggy very uneasy for fear we shall all perish with hunger we have but a little meat left & only part of 3 hides has to support Mrs. Reid she has nothing left but one hide…”

— February 5, 1847

“… J Denton trying to borrow meat for Graves had none to give they have nothing but hides all are entirely out of meat but a little we have our hides are nearly all eat up but with Gods help spring will soon smile upon us”

— February 10, 1847

“… Mrs Graves refused to give Mrs Reid any hides, put Suitors pack hides on her shanty would not let her have them. says if I say it will thaw it then will not, she is a case”

— February 15, 1847

“… shot Towser today & dressed his flesh. Mrs Graves came here this morning to borrow meat dog or ox. they think I have meat to spare but I know to the Contrary they have plenty hides. I live principally on the same”

— February 23, 1847

“… The Donnos told the California folks that they commence to eat the dead people 4 days ago, if they did not succeed that day or the next in finding their cattle then under ten or twelve feet of snow…”

— February 26, 1847

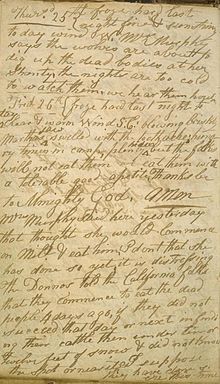

Here’s an actual sample of Breen’s diary:

Page 28 from the diary of the Donner Party’s Patrick Breen, recording his observations in late February 1847, including “Mrs. Murphy said here yesterday that she thought she would commence on Milton and eat him. I don’t think she has done so yet; it is distressing.” (about 3/4ths of the way down the page)

Page 28 from the diary of the Donner Party’s Patrick Breen, recording his observations in late February 1847, including “Mrs. Murphy said here yesterday that she thought she would commence on Milton and eat him. I don’t think she has done so yet; it is distressing.” (about 3/4ths of the way down the page)

Rescuers from California attempted to reach the emigrants, but the first relief party did not arrive until the middle of February 1847, almost four months after the wagon train became trapped. Of the 87 members of the party, 48 survived to reach California. Historians have described the episode as one of the most spectacular tragedies in Californian history and in the record of western migration. 3

The tragedy is dramatized in a 2009 feature film and documented in a PBS American Experience episode, both titled “The Donner Party.”

End of Part 1. To Be Continued

_________________

*Here’s a panoramic view of Donner Pass, by the great American landscape artist Albert Bierstadt:

Albert Bierstadt (American, 1830-1902)Donner Lake from the Summit, 1873Oil on canvas: 72 1/8 x 120 3/16 in. (183.2 x 305.3 cm)Gift of Archer Milton Huntington, 1909.16

1. Jack Kerouac, On The Road: The Original Scroll, 1957, edited by Howard Cunnell, Viking, 2007, 123.

2 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Salt_Lake_Desert

3. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donner_Party

Lorrie Moore’s Bark book cover, courtesy ofblogspot.com

Coltrane, Courtesy hqwallbase.com

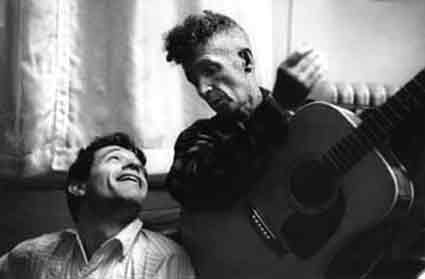

Coltrane, Courtesy hqwallbase.com John Coltrane, in the background right, steps back for a saxophone solo by his musical acolyte Pharaoh Sanders at the Temple University Concert. Liner photo courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, University of California, Santa Cruz & The Frank Kofsky Archives.

John Coltrane, in the background right, steps back for a saxophone solo by his musical acolyte Pharaoh Sanders at the Temple University Concert. Liner photo courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, University of California, Santa Cruz & The Frank Kofsky Archives. John and Alice Coltrane. Photo coutesy of lounge.obviousmag.org.

John and Alice Coltrane. Photo coutesy of lounge.obviousmag.org.

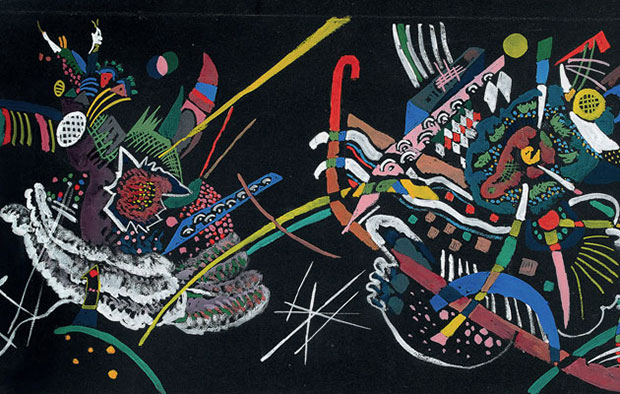

In Gray, 1919

In Gray, 1919 Yellow-Red-Blue

Yellow-Red-Blue

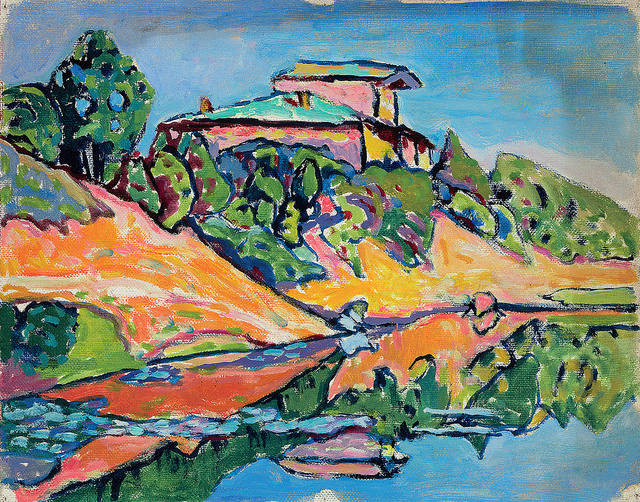

Fragment 1 for Composition VII Composition IX Old Town II

Fragment 1 for Composition VII Composition IX Old Town II  Old Town II

Old Town II Painting with a red mark 1914

Painting with a red mark 1914  Improvisation III

Improvisation III