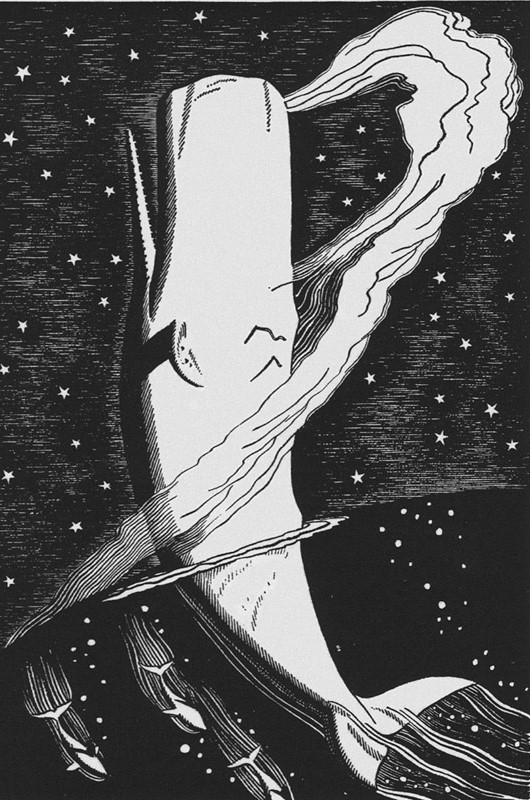

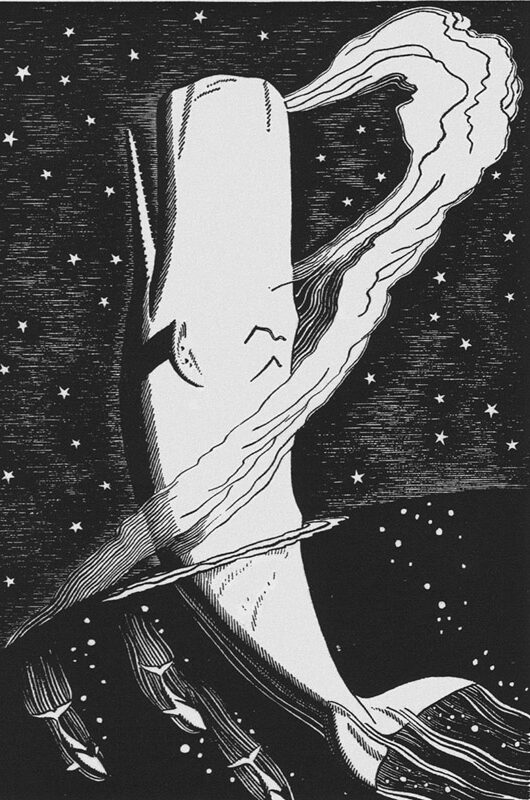

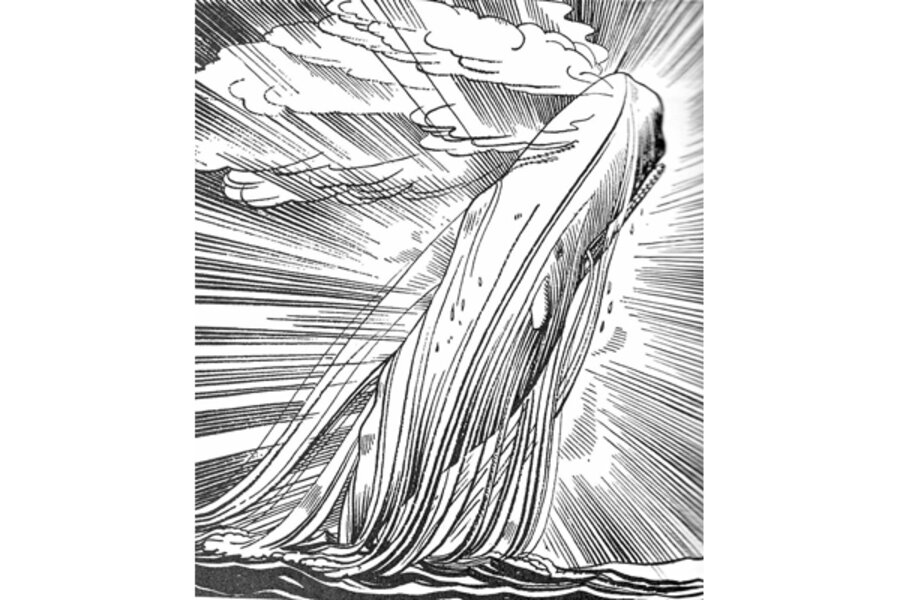

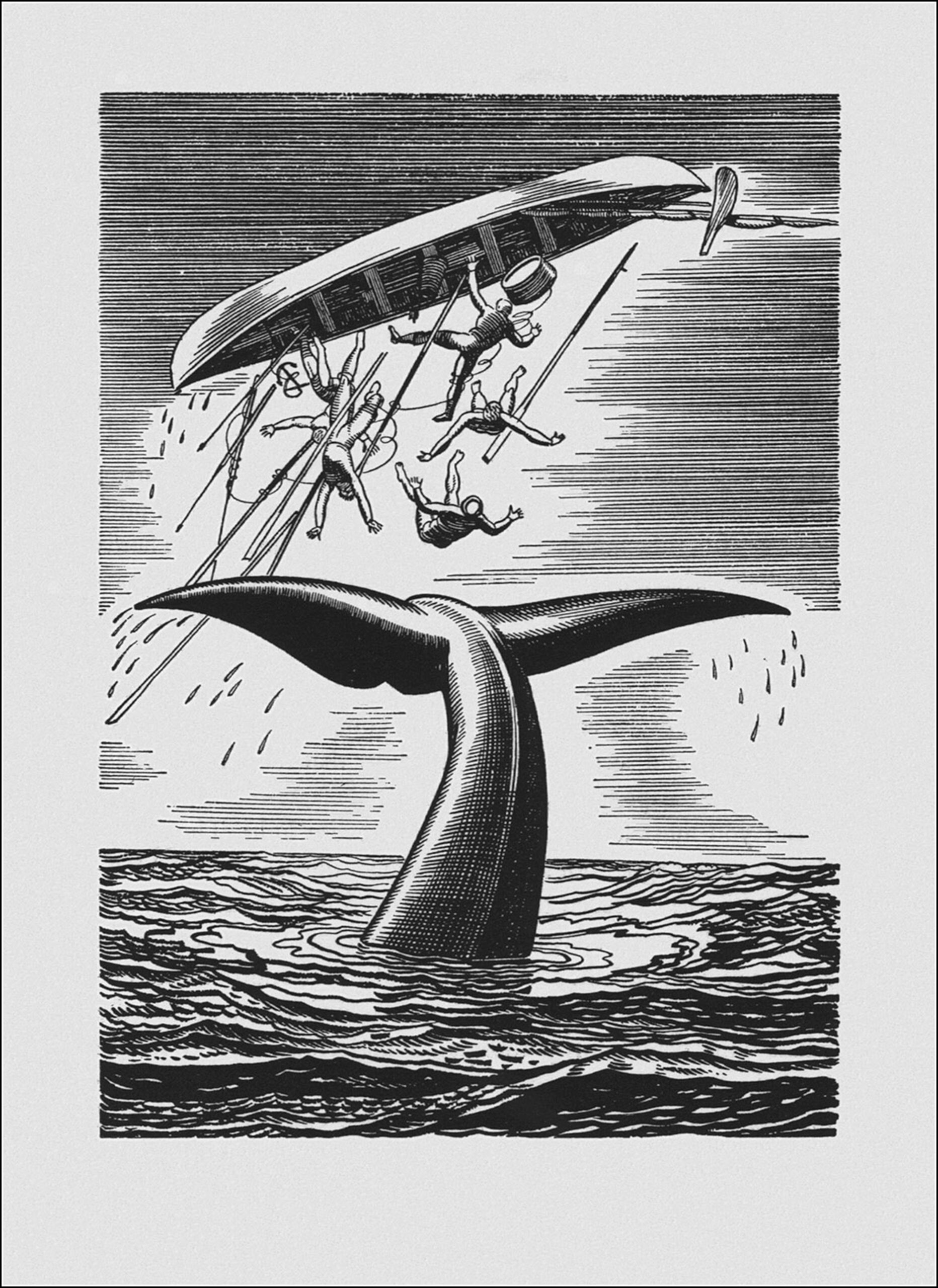

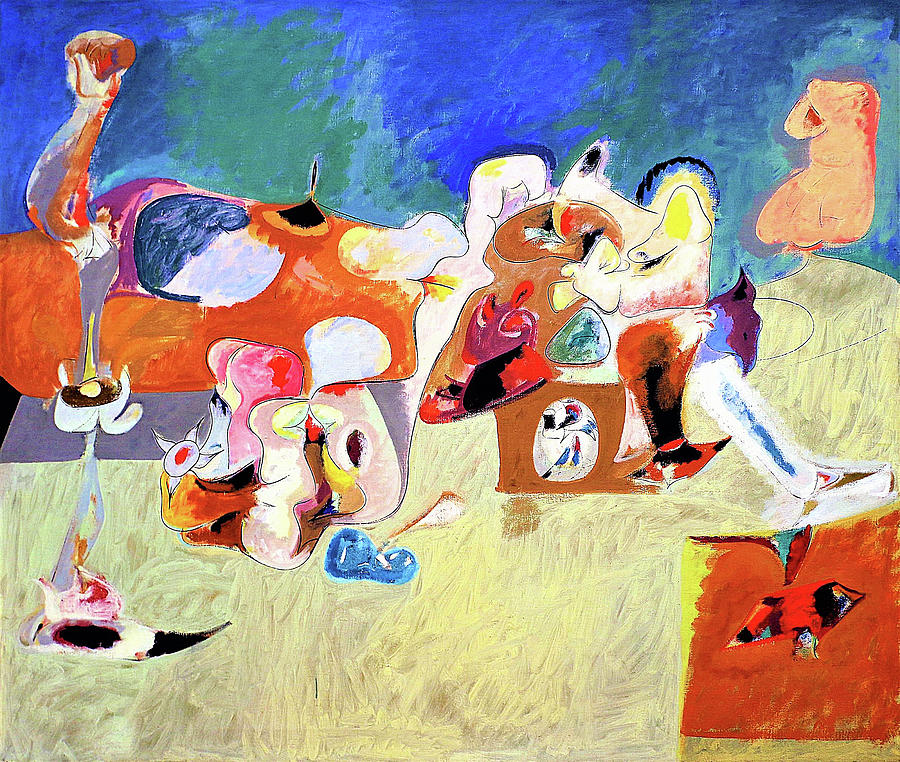

For me, this is Rockwell Kent’s most magnificent evocation of Moby Dick. We see him breaching in the night, an act of exultation which demonstrates his godlike presence in the sea, and his cosmic relationship to the heavens. This is hardly an evil whale.

Moby-Dick prints by Rockwell Kent

And then there were humans and leviathans, both pursuing light and the night. Where to? Why? Because Ahab is evil? Or is the white whale? Melville found horror in whiteness, but his profound and prescient chapter on the subject deflects nearly as much as it reflects.

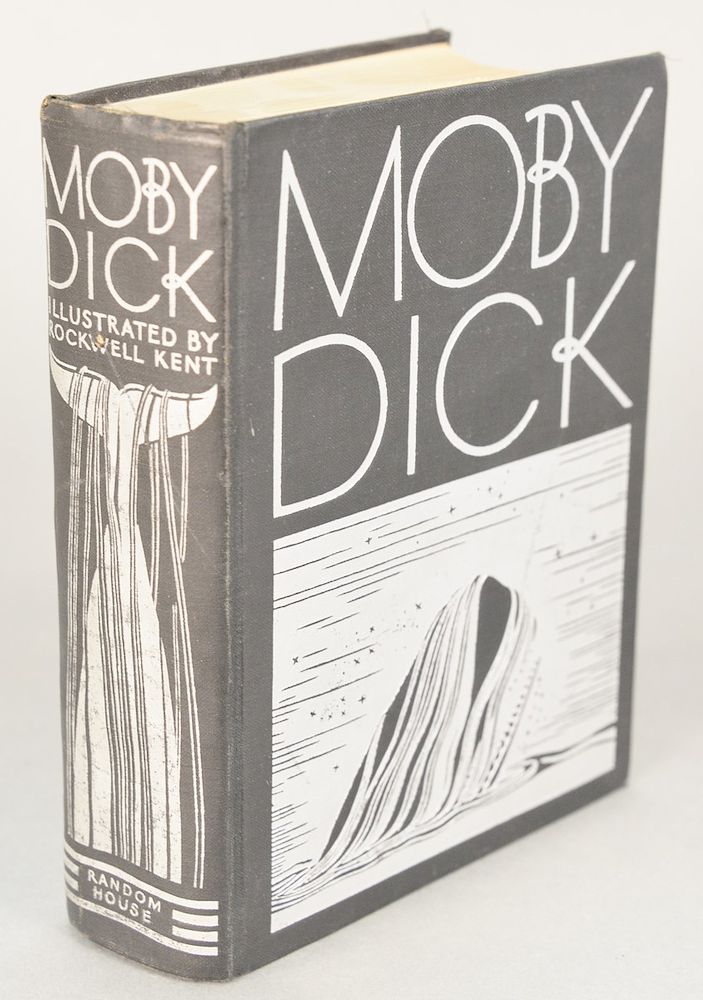

For artist Rockwell Kent, deep in that same pursuit, the devil was in the details, the textures of truth. Enter here. You may begin to feel the night engulfing, and lacerating. Kent actually produced 280 noir-Deco woodcuts for the 1930 Random House edition of Moby-Dick, and so charged the era’s imagination that Melville’s behemoth tale, long homeless for a meaningful audience, became palatable, bite by bite. The 135 short chapters, such an orgy of wonder and mystery, found their brethren in images.

And the forsaken story finally found its audience, with the printmaker’s incalculable assist. I recently responded to an NPR survey about the single work of art that changed one’s life, and chose this book, and shared how Kent’s work primed me for the great American odyssey. But another recent blog, from which most of these images are borrowed, prompted me to flesh out Kent’s work more than before. That blog, A Smart Dude Reads Moby-Dick, is also recommended especially …for Moby-Dick doubters and procrastinators.

https://avidly.lareviewofbooks.org/2012/09/20/a-smart-dude-reads-moby-dick-episode-1/

Begin with zealous artistry, probing atmosphere and characterization, and tale-spinning flourish, if I may offer something of the meaningfulness of these images. I invite you to soak them up and read the short comment texts included. You may be on your way to the sea’s beckoning horizon.

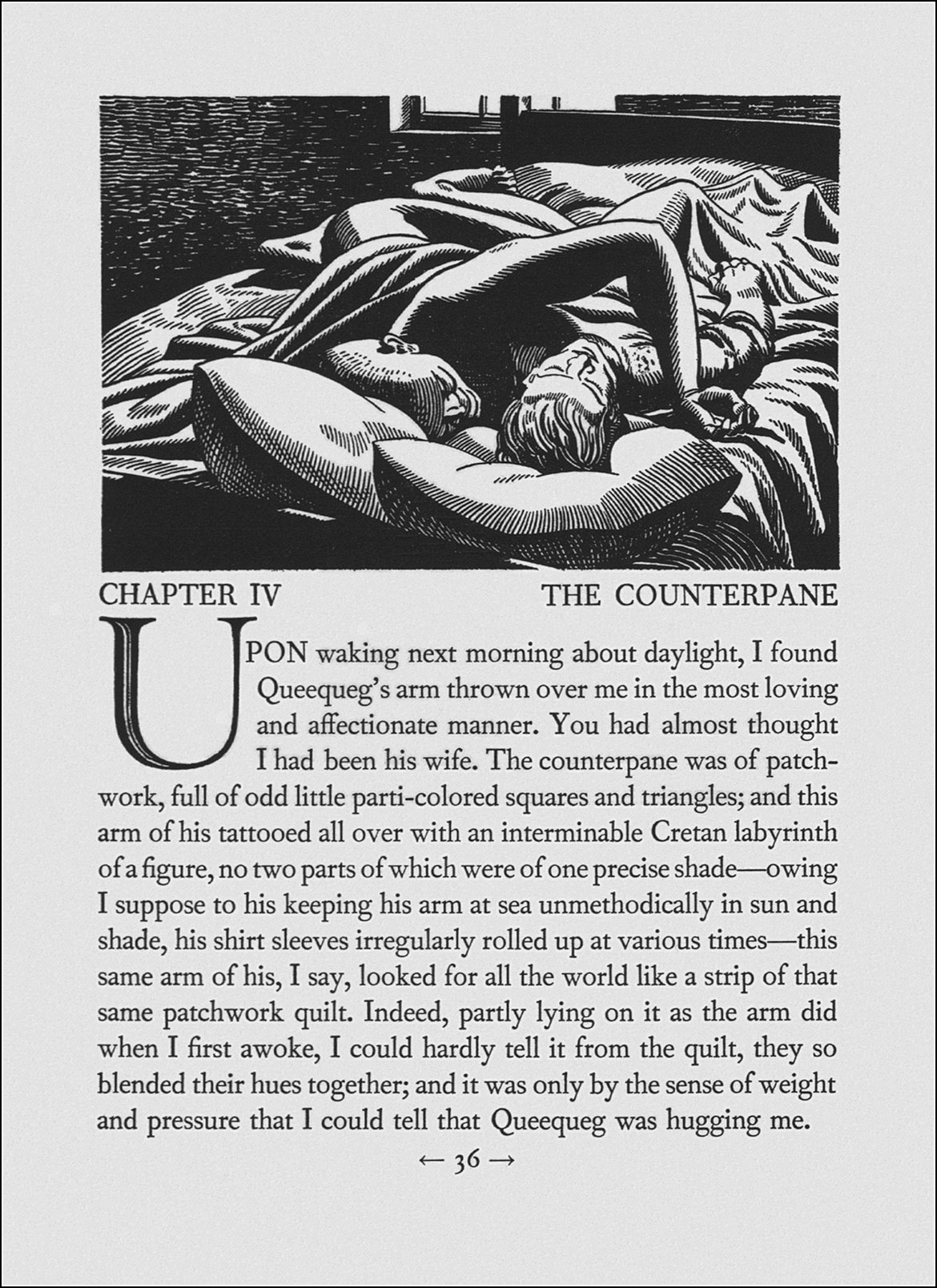

Some include full-page reproductions of Melville’s book, with text and illustration, for a counterpoint of mind and eye, from the ground-breaking 1930 edition (still available in a Modern Library a paperback edition). Kent was a knife-wielding poet of shadow and light, as you begin to see in the first image, from the chapter entitled “The Counterpane.” The counterpane (quilt) and arms dance amid their rest. In the text, notice how narrator Ishmael focuses on the visual effect of his experience. But in that moment? Where do dreams go to live, or die? Comedy lies waiting, as much as fate, but so much more!

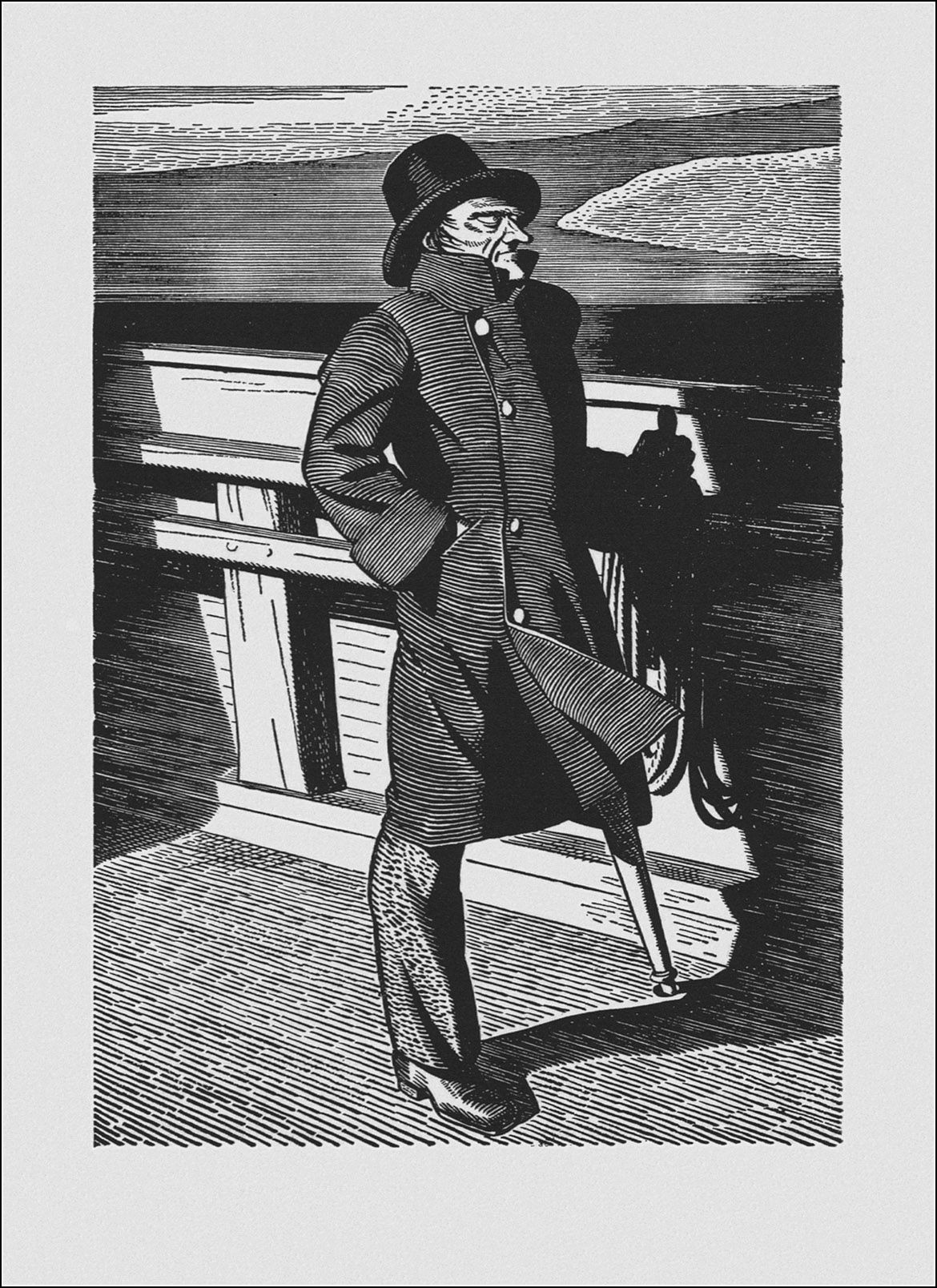

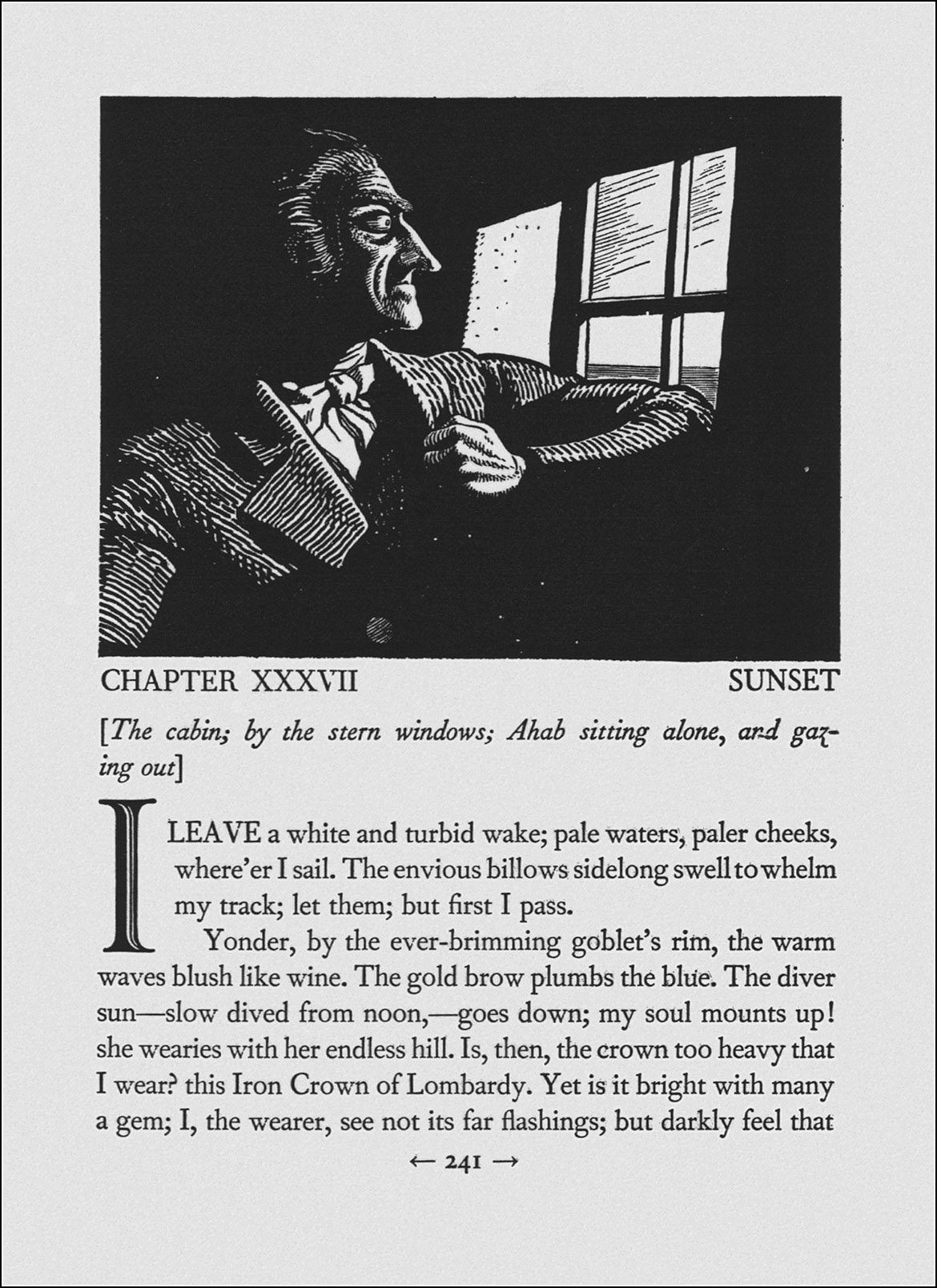

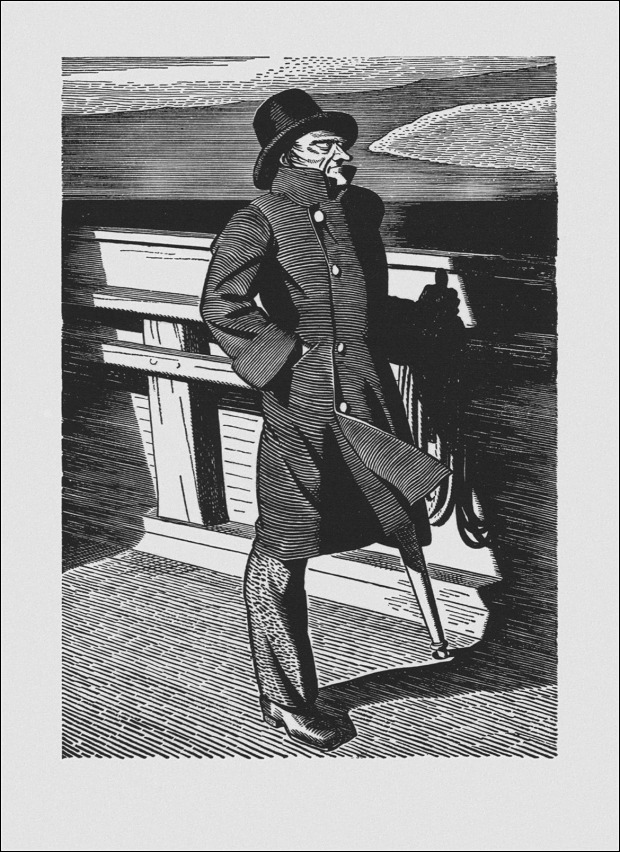

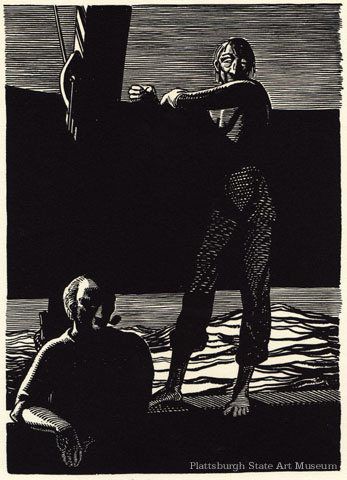

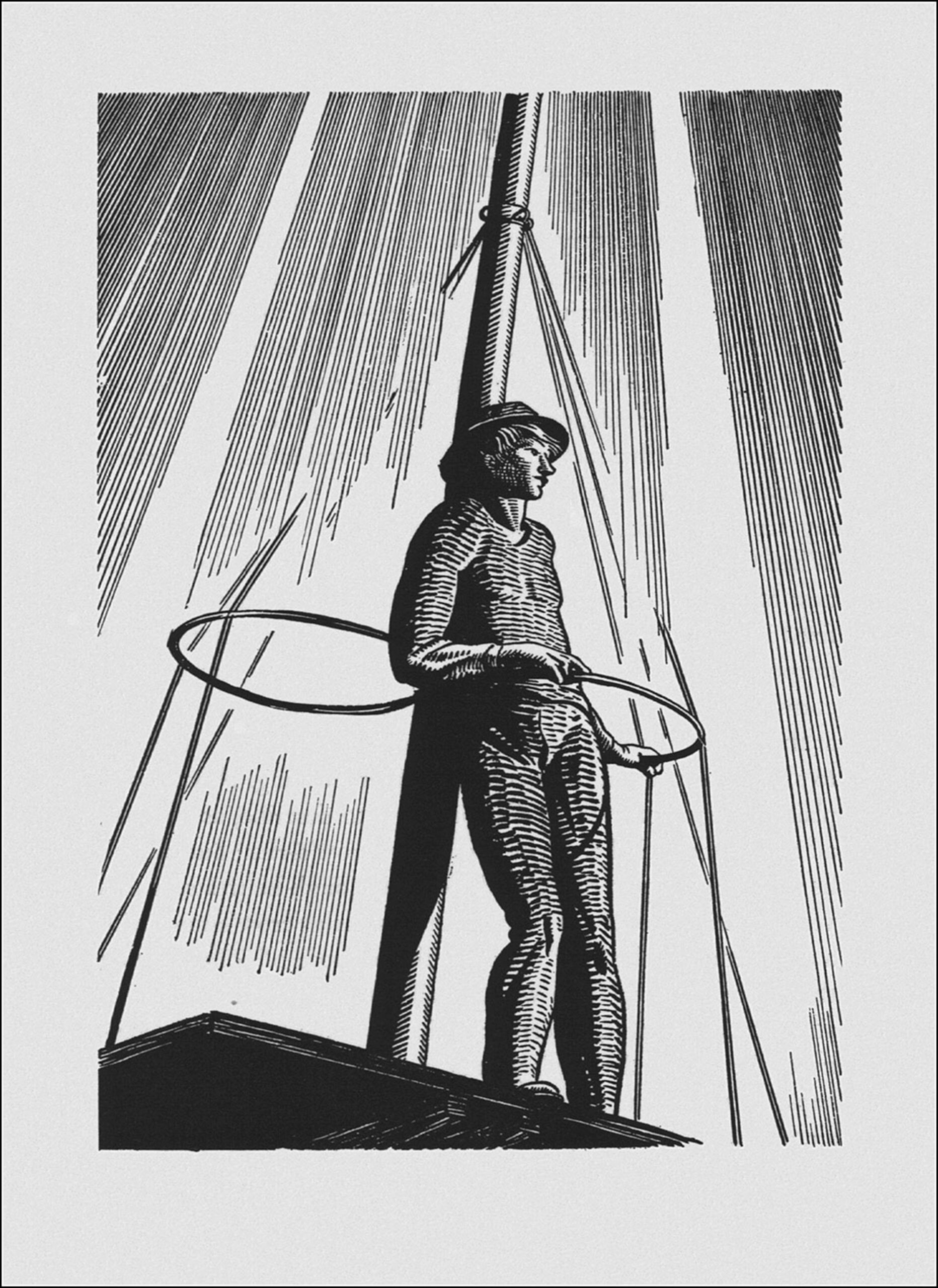

Below, we see Ahab (who doesn’t appear in the book until Chapter 28) in two telling moments. First, he gazes defiantly into the sea light, infernal for him. We then should let Melville’s words introduce him, with the first page of “Sunset” (Chapter 37), our post’s first indication of the narrator’s sense of the power of atmosphere for his story, and for his subject. The second image below shows Ahab full-figure, master of his domain, if not of his wretchedly magnificent mind. Note the small hole in the deck carved out to steady his whalebone leg — Moby-Dick’s hellish handiwork, and the virtual spleen driving the tale.

Below, we see Ahab (who doesn’t appear in the book until Chapter 28) in two telling moments. First, he gazes defiantly into the sea light, infernal for him. We then should let Melville’s words introduce him, with the first page of “Sunset” (Chapter 37), our post’s first indication of the narrator’s sense of the power of atmosphere for his story, and for his subject. The second image below shows Ahab full-figure, master of his domain, if not of his wretchedly magnificent mind. Note the small hole in the deck carved out to steady his whalebone leg — Moby-Dick’s hellish handiwork, and the virtual spleen driving the tale.

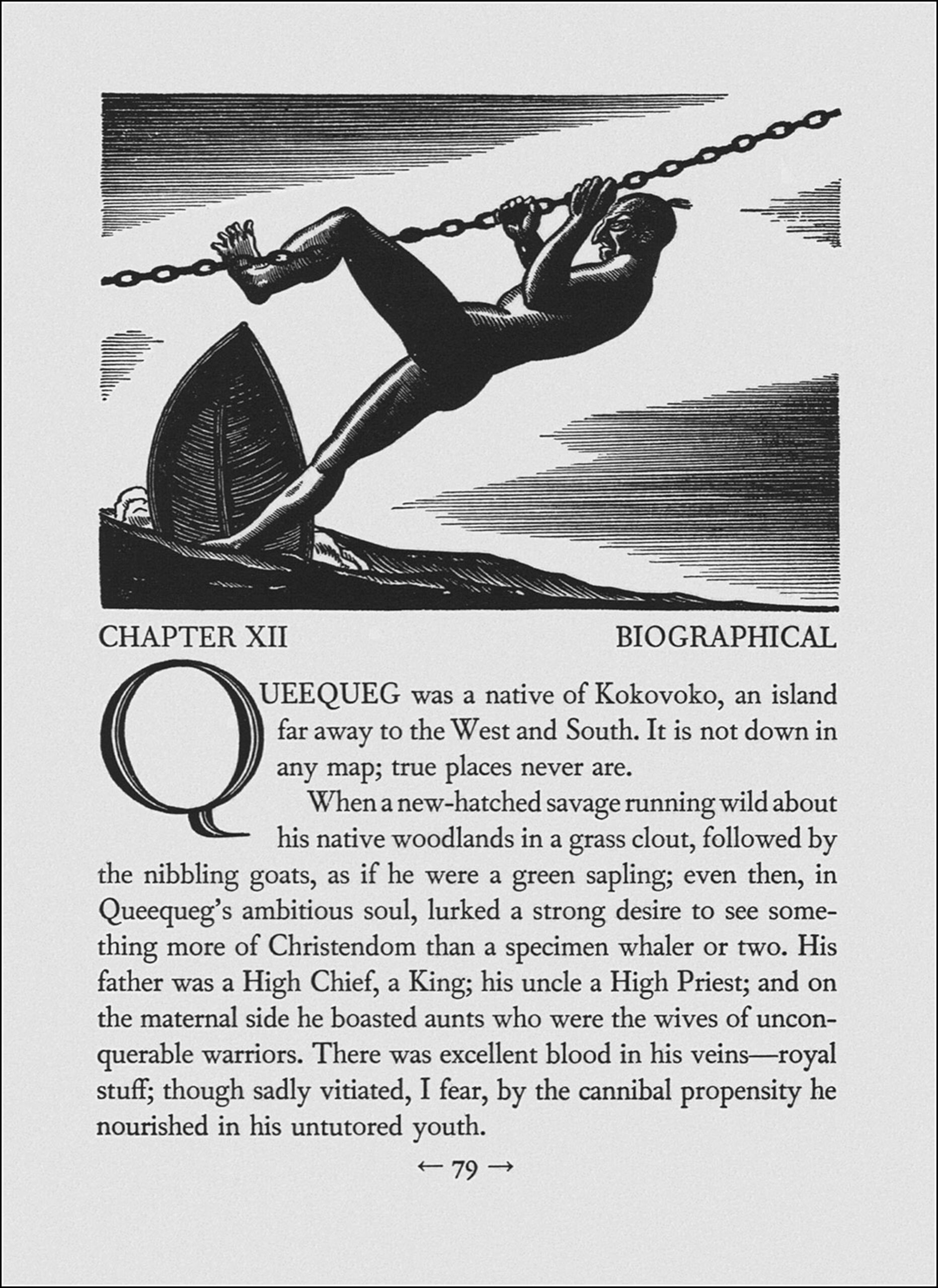

Arguably the second most colorful character in Moby-Dick besides Ahab (if not Moby Dick himself) is the Polynesian first harpoonist Queequeg. Covered with tattoos, he’s a king in his native land; sells, and prays to, shrunken heads; and memorably befriends the narrator, a relationship that, in its way, begets the whole story, as the final chapter reveals. Here Melville introduces Queequeg in the chapter “Biographical.” The scene depicted may reference a later chapter, “The Monkey Rope” where he attempts a stunt-like action during whale-cutting with Ishmael, situated at the other end of the chain. He saves Ishmael’s life.

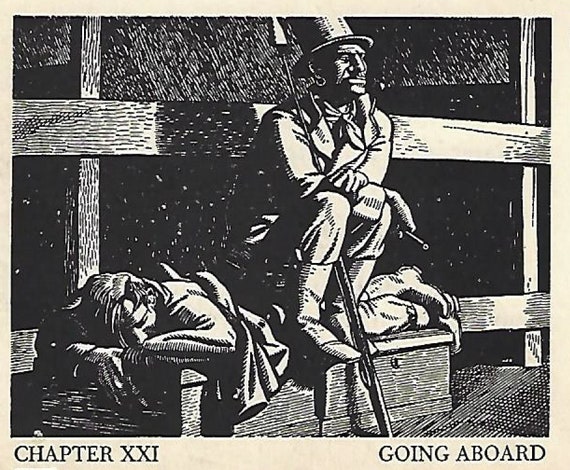

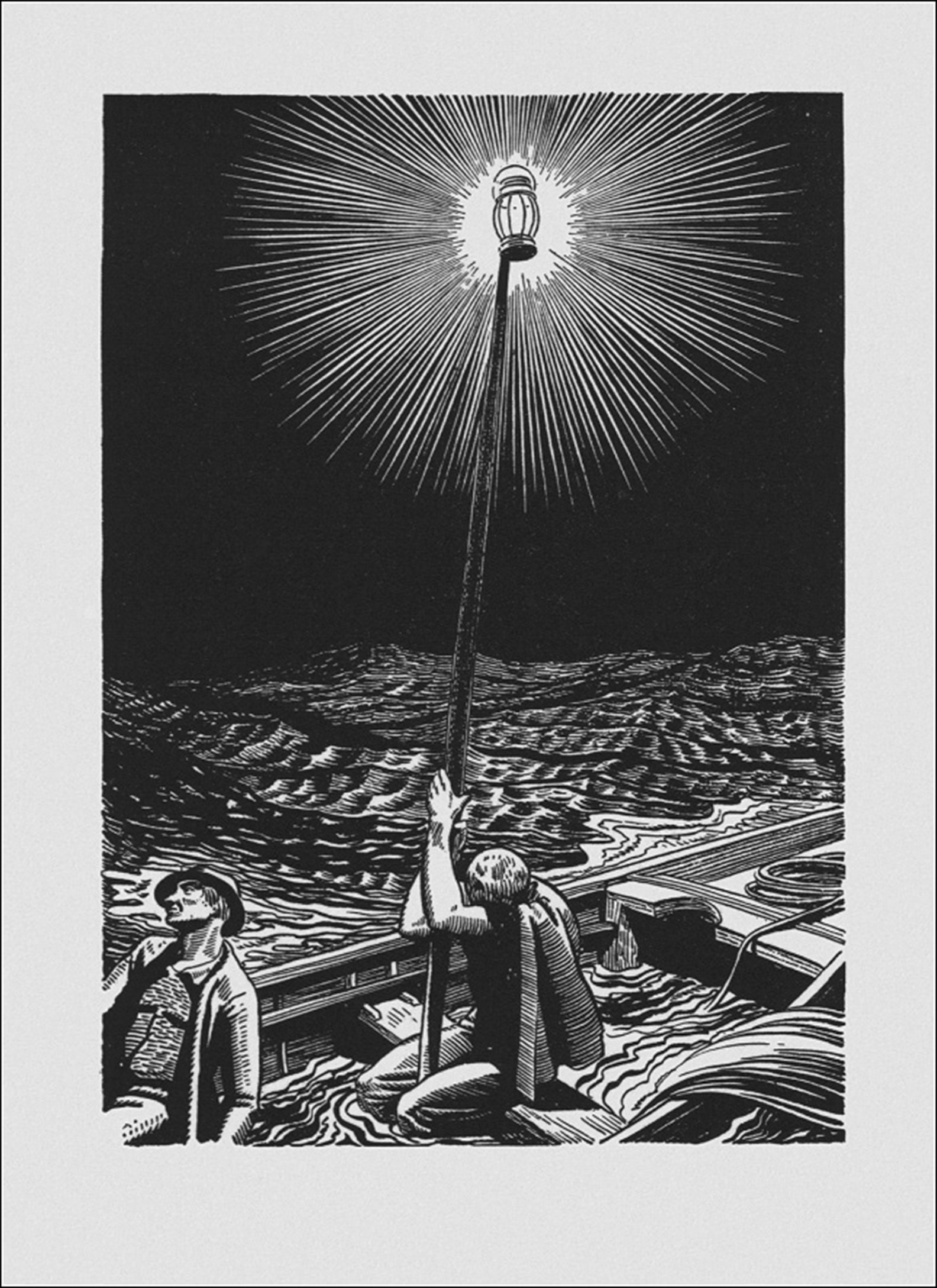

This print below exemplifies Kent’s mastery of what would become known as noir atmosphere, which would almost simultaneously begin being exploited by film-makers (see previous blog):

NPR American Masters question: What single work of art changed your life?

. The two crew members and the backdrop create a stunning mood and composition, with Kent brilliantly sculpting light and darkest shadow. Perhaps such a scene was inspired by Melville’s contemplation of “the darkness of blackness,” an inherent American condition, he believed, derived from the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne, the great writer to whom Melville dedicated his masterpiece.

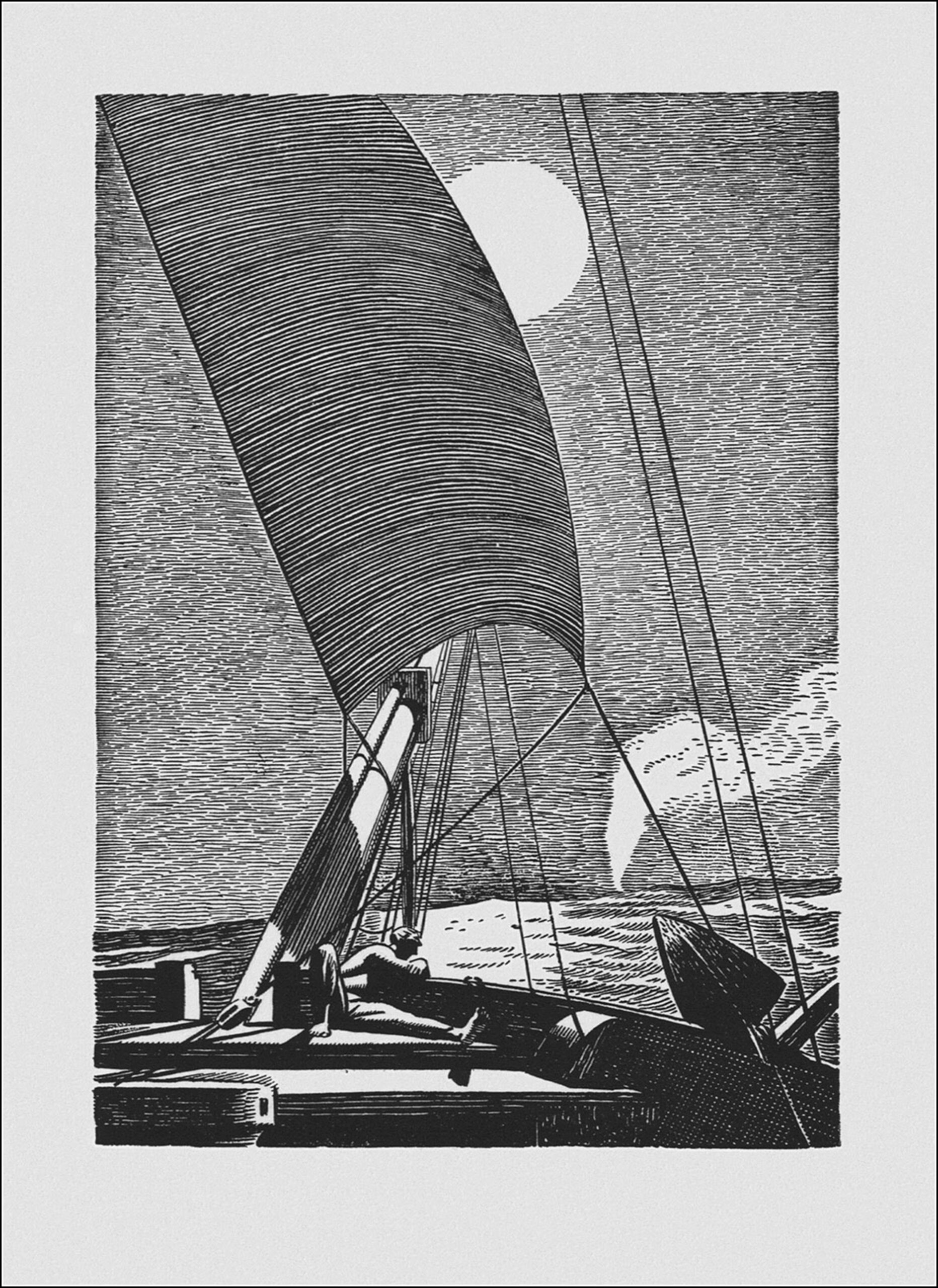

The following three prints share a beautiful affinity and, thanks to a blog’s latitudes, I decided not to choose among them. Rather, I want to allow them together, along with the preceding print, to cast a long shadow of spiritual striving and unease, from Kent to you. Such stunning atmospherics might take him anywhere in his artistic quest. But he was working very much in Melville’s expansive and doomed milieu. Such strangeness, such black beauty. It was genius meeting genius.

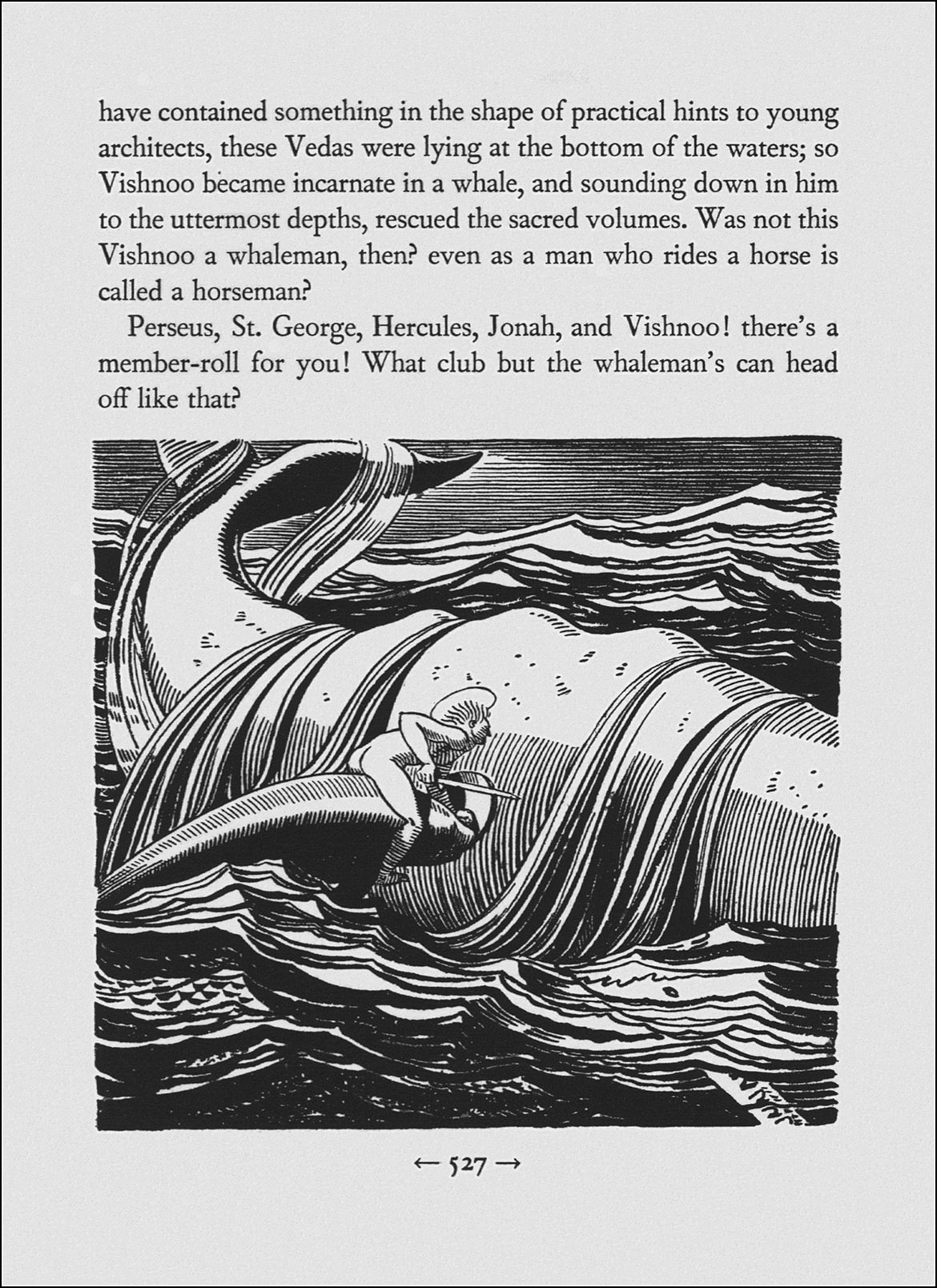

Below, we get a taste of the deep learning pervading this epic. Here the mythological character Vishnoo alights upon a whale with seeming preternatural ease. Ishmael compares him heroically to Hercules, St. George, and Jonah, aptly it seems. Yet he’s not an immortal God, rather but one dueling with destiny.

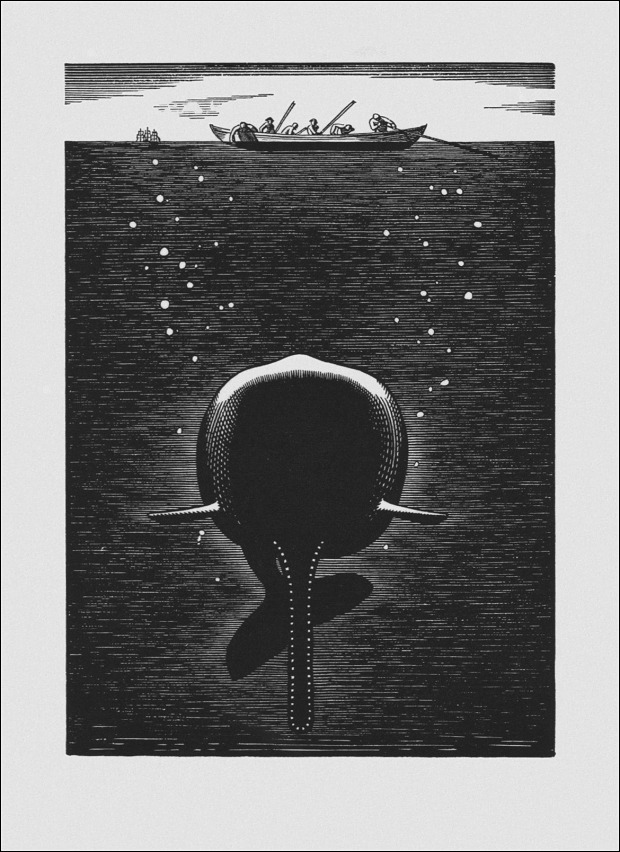

For me, this below is one of Kent’s most breathtaking images. Is he taking artistic license with the scale between the whale and whaling boat? To a hardy crew at sea for many months, stretched to their human limits, having to live with the existential risk of the whale hunt, it may hardly seem an illusion.

And finally comes the long-awaited chase of the White Whale, now successfully transformed into a hated entity by the demagogic Ahab, hypnotizing his crew, all but first mate Starbuck. And then, “He raised a gull-like cry in the air, ‘Thar she blows! — Thar she blows! A hump like a snow-hill. It is Moby Dick!’ ” Here we see natural excitement foaming with the monomaniacal captain’s greed and vengeance.

Artist Rockwell Kent demonstrates above the spectacular power of Moby-Dick in this image. Kent’s work predates a number of brilliantly-realized illustrated editions of the book. But, for me, that edition has never been surpassed. For example, the image above I believe inspired the cover of a 2007 edition of the novel, a “Longman Critical Edition” (below). But that striking yet odd Longman image fails to show the source of the explosive disruption, the whale himself.

Courtesy amazon.com

However, as successful artistically and commercially as the Kent-illustrated volume was, it had one glaring flaw, readily evident on the cover (below). There’s no indication that Herman Melville is the author! Rockwell also designed the book cover, which might help explain how Melville’s name was overlooked. Marketing doubtlessly had the other hand in that decision. Random House likely figured they had a great coup with Kent’s illustrations. In the Art Deco 1920s, he may have been better-known than Melville himself. It was yet another of a long series of insults and betrayals — now posthumous — to a great American writer who struggled mightily for his art, and to support a large extended family. 1.

___________

- Picky pedantics might also object that the Random-House cover failed to hyphenate Moby-Dick which was Melville’s chosen title (subtitled “Or, The Whale”) for the book, even though the whale’s name in the book’s text has no hyphen.

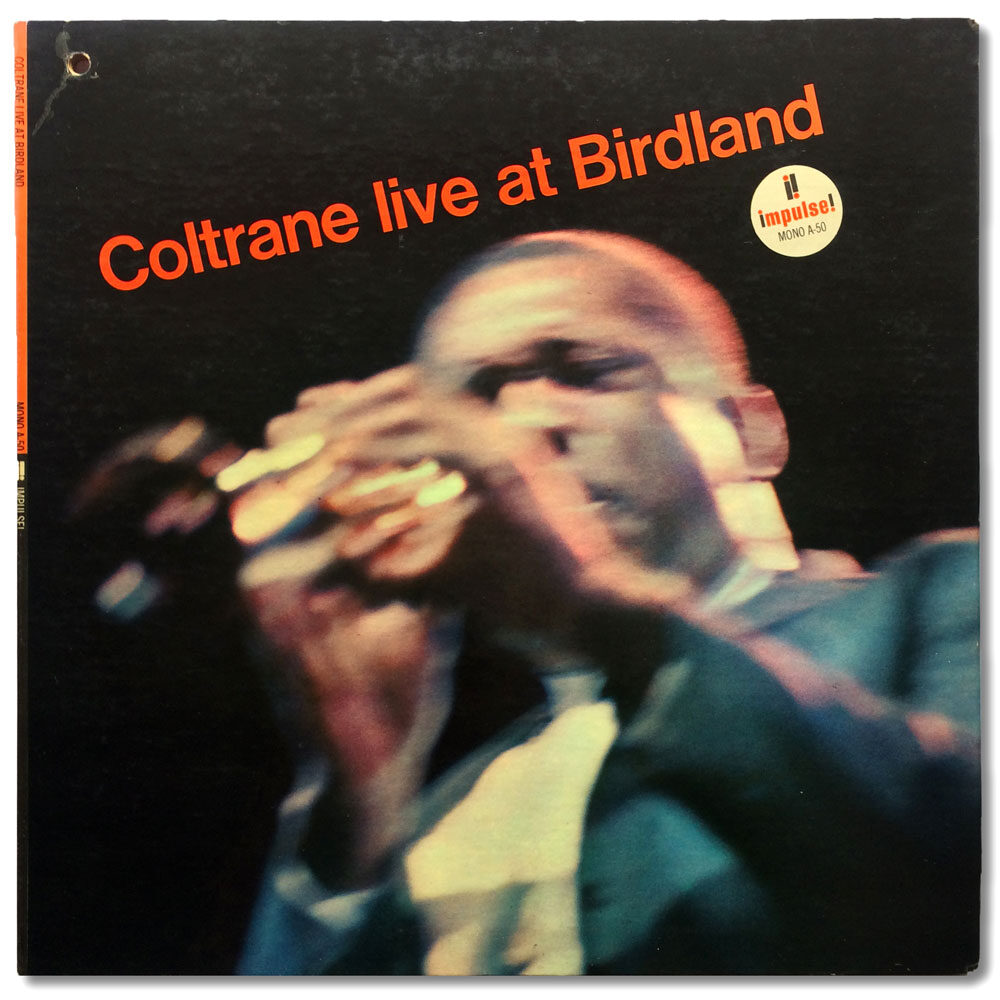

John Coltrane “Live at Birdland.” Courtesy deep groove mono

John Coltrane “Live at Birdland.” Courtesy deep groove mono