Review: The Eye You See With by Robert Stone (Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt)

As he traversed the earth, the sun also rose for the writer Robert Stone, even amid deep spiritual shadows. And the hardness of his courage shone in the glinting light, as many sweated, suffered, and died. As did he, eventually, in 2015.

He was like a carved-granite eagle in flight. He ventured to high vistas of perception, as an intellectual warrior, and dove, as a miner of humbled but ambitious soul, as it arose in the 1960s. He became very close to some iconic figures, including Ken Kesey, the acid- “enlightened” novelist (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) and charismatic leader of the hippie rogues, The Merry Pranksters.

But he’s worth revisiting or discovering for many reasons.

Though primarily a novelist, Stone re-emerged recently with a far-ranging posthumous collection of his non-fiction, The Eye You See With. 1 The title gains centrality this way: “The eye you see with is the one that sees you back.” That is Stone’s distillation of a sermon by Meister Eckhardt, and Stone was “obsessed with the absence of God…everywhere we look there seems evidence of (the divine presence), and it never yields itself to our discovery.” 2

So, some of the most compelling truths remained the most elusive. Ah, but the world and universe the creator wrought were out there waiting, beckoning. Though a tough-minded man and Navy veteran, Stone’s poetic power and his Catholic upbringing braided his consciousness, and his nearly relentless questing for truth.

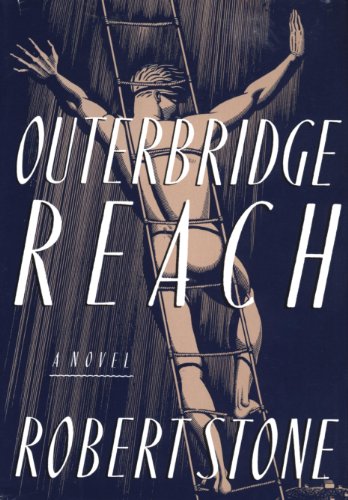

Stone’s big subject was America, which he said he was striving to define through his work, a measure of his ambition, though he never said he was close to accomplishing that. Yet he kept chiseling away at the stone by taking a global attack, traveling literally, and through his story-telling, to points as far as around-the-world, in the sea-faring novel Outerbridge Reach, and, in others, with intense focus, in Central America, The Caribbean, and the Middle East.

Robert Stone visually evoked, for a novel cover, his admiration of Melville’s genius by borrowing one of Rockwell Kent’s iconic woodcuts for “Moby-Dick,” 1930 Random House edition. Amazon

And yet, for that ostensibly broad contextualizing perspective, his focus was always very specific in story and characters, whom he often prodded to evaluate America and pose questions about it and, by extension, humanity. 3

He first really caught my attention with his novel A Flag for Sunrise, nominally echoing Hemingway, which set an American anthropologist Frank Holliwell in Central America during the same era the U.S. was politically ensnared in the revolutionary chaos of that region. Local corruption interfaces with the religious, as Holliwell helps protect a Catholic mission from bad federales, he falls in impossible love with a missionary nun. His dilemmas, which include previously having been morally compromised in Vietnam, resound metaphorically with America’s.

Stone’s most ambitious novel, Damascus Gate, mirrors in prose, Melville’s epic storytelling poem Clarel – both describing pilgrimage-like trips to The Holy Land by Americans, among others. That setting allows for powerful moral situations and conundrums, as well as plenty of human drama and suspense, set in the bloody dust of Jerusalem.

“Varieties of religious experience for the millennium,” wrote author Frank Conroy of the novel. “By turns scary, funny, and deeply moving. Prose at such a high pitch it sometimes seems hallucinatory. Stone is a genius.”

Accordingly, in the nonfiction essays of The Eye You See With, Stone addresses, sometimes at a very personal level, the dichotomies and contradictions of patriotism, and of religion, while scoring its relevance. His eyes and mind are flung wide open hearing jazz saxophonist John Coltrane’s spiritual fire.

He wrote prophetically in the mid-’80s that we should resist the facile “Great America” rhetoric, which has echoed from Reagan to Trump, because the nation has betrayed its own ideals so often.

Stone the reporter underscores this hypocrisy when he does door-to-door census polling in the slums of New Orleans, in the extravagant shadows of the Superdome, which supplanted an African-American neighborhood. One black family is grappling, it slowly dawns on him, with a dying family member. Yet with a calm grace they allow him in their front door for census questions. This family is about to become less, by one. Stone reflects: “Had this been a white, middle-class household, I would never have been allowed past the door… I would never have dreamed of entering a sick room, approaching a deathbed, asking cold, irrelevant questions of people who had come to mourn and pray. What has happened here is entirely determined by the politics of race and class – how blinding it can be, how dehumanizing, how denying of basic human dignity.” 4

In “A Higher Horror of Whiteness,” an essay originally published in Harper’s, Stone also hitches up to Melville’s uncannily “prophetic” insights from the mid-19th century, on the mysterious qualities of “whiteness.”

Stone’s chapter, from 1986, draws deeply from Melville’s famous “Whiteness of the Whale” chapter in Moby-Dick, in contemplating the insidious powers and qualities of cocaine, not just it’s inherent whiteness but a “metaphysical whiteness” akin to that which Melville patiently draws out the horrors of. Early in his meditation, the elder author even acknowledges, amid an extraordinarily-suspended sequence of dependent clauses, the role the “colorless color” plays in “the white man’s ideal mastership over every dusky tribe.” Yet that notion slowly dissolves in irony under the ensuing complexity of associative, cultural and instinctive forces, the haunting horrors within whiteness, which Melville expands on. Stone follows Melville quite a ways in this chapter.

So Stone and Melville resonate to the moment, in which the instinct of possessing whiteness in oneself seems a perceptual pitfall, “so that all Deified nature absolutely paints like the harlot,” as Melville asserts, near his conclusion. This delusory effect manifest itself as an anarchist, racist, and deadly mob attack January 6 on the U.S. Capitol, led by white supremacists and Neo-Nazi Trump-followers.

Stone quotes Melville: “but not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul… And yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind…a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows – a colorless, all color of atheism from which we shrink.” 5

Updating the profoundly agnostic Melville’s context of the word “atheism,” the term takes various forms today. But the message here is the lack of faith – in pluralistic American values and democracy – which obscures those blinded by their whiteness and radicalized away from their own interests, in thrall of the demagoguery of a cult-like leader vying for totalitarian power. Or blinded, as Stone might say, by the white-bound limits of “the eye you see with.”

Many, including President Biden, have commented on the easily breached resistance to the mob by the undermanned (by Trump) Capitol police – compared to previous violent police crack-downs on peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters – as a prime example of “white privilege.” Melville, of course, created the archetypal American demagogue with Captain Ahab, who nevertheless plays out as a tortured, bedeviled hero, pursuing the truth behind “the pasteboard mask.” By comparison, Trump, and his lying and poisonous rhetoric, play out as something quite below, perhaps clinging barnacle-like under the nation’s hull, hidden in the whiteness of the prow’s surf.

In many ways, Stone addresses American experience in these essays, which often read as travelogues, making them extremely palatable when they venture into political and philosophical discussion.

He bravely called out the military kingpins for their corrupt power warfare:

“On one (Vietnamese) hill they lost 56 men, and a general explained that Hill ‘had no military value whatsoever.’ There seemed to be a contradiction.” 6.

Nor does he slink from revisiting questionable in-country strategic calls:

“General Westmoreland was not a sophisticated man, and he appears not to have realized how gravely the cards were stacked against him. His declared tactics of search and destroy – finding and eliminating the enemy’s main force – turned to rubble in his hands.” 7

The more you read, the more you begin to understand the stony toughness of this writer, akin to, at least, the mythical Hemingway.

And Stone’s embracing of the relevance of religion reveals him unafraid to acknowledge a dark vision of God.

Cover of a book series edition Robert Stone contributed to. Amazon

The author comments:

“Because God welcomes all who give up their lives in his name. Because he will not be mocked. He wants his friends to kill his enemies. His beloved go forth to battle and leave heaps of slain.” 8

For all that, he’s also bracingly insightful about the faults of writers he admired, even with grave reservations:

Graham Greene “was tortured almost to a suicide by a grammar school mate.” This might explain Greene’s seemingly misanthropic spiritual malaise, his grieving, as a devout Catholic, of declining moral standards.

I allude to other iconic writers because Stone strikes me as a rare contemporary of our times who stands shoulder-to-shoulder with them, in ambition and talent, as if they’re aligned on a schooner ship that lists and tilts our perspective on them. Stone’s meaty topics and settings are engagingly rendered, and resonant — they grab the high winds, even if they be treacherous. He pulls you in with a pop-culture subject like Hollywood, then turns it inside-out to expose a rotting underbelly, the business that eats actors alive, but also the dazzle and beauty of the art remaining, damaged and infected, spotlighting the poignance of faded artistic power and grace. The drug and psychosis-effected narcissists in his novel Children of Light seem like names on a theater marque barely visible in a misty haze of dark impressionism, weak stand-ins for themselves — and agonizingly for one actor, Lu Anne Bourgeois, who feels deeply kindred to Rosalind in As You Like It, perhaps Shakespeare’s greatest female character, whom she’s played triumphantly in the past.

Shakespearean overtones, no less. As Melville once proclaimed, praising Hawthorne, “Shakespeares are this day being born on the banks of the Ohio.” Why not? Where does artistic rarity reside? Yes, Stone not infrequently achieves a resonance in time, a spiritual aroma that lingers like a haunting. That’s partly why he is always worth pursuing again, down the road. It’s why we’re thankful for novelist Madison Smart Bell for assembling and curating this collection. 9

Stone fearlessly casts a view ahead, and reports from the portal of the mortal or moral “heart of the matter,” to evoke Greene’s metaphorical courage and ambition.

But Stone was his own man, resembling, in words at least, the beautiful and sui generis human form the genius sculptor untombs with his chisel.

______________

1. Also worth reading is previous non-fiction by Stone, the memoir, Prime Green, Remembering the ’60s, P.S. Paperbacks

2. Madison Smart Bell, Introduction to The Eye You See With by Robert Stone. HMH, xxi

3. Stone’s National Book Award-winning novel Dog Soldiers takes aim at America’s greatest foreign policy folly to date, The Vietnam War, and was adapted into a 1978 film, Who’ll Stop the Rain, starring Nick Nolte.

4. Stone, “Keeping the Future at Bay,” The Eye You See With, 179

5.. Stone, “A Higher Horror of Whiteness,” The Eye, 209

6. Stone “A Mistake Ten Thousand Miles Long,” The Eye, 41-42

7. Stone, “Out of a Clear Blue Sky,” The Eye, 104

8. Stone, Images of War (The Vietnam Experience), 104

9. Bell is also the author of Child of Light: A Biography of Robert Stone, Doubleday 2020.