A Southerly Cultural Travel Journal, Vol. 1

“Ahab’s cabin shall be Pip’s home henceforth, while Ahab lives.” – Moby-Dick, Heritage Press, 1948, Illustration by Boardman Robinson

(NOTE: I decided to re-post this blog column because it seems even more pertinent than ever with the current convolutions of the George Zimmerman second -degree murder case.)

This first posting documents an incident that occurred on my train ride back north to Milwaukee from Carbondale. However its timeliness and troubling nature allowed it to rise to the surface).

The black youth settled in beside me on the train and within minutes pulled his hood up and seemed to doze off to the gently numbing rhythms of Amtrak. Glancing at him, I figured he was in his mid-to-late teens and, of course, I thought of the late Trayvon Martin. Sadly, this boyish male was risking profiling and even racist threat by wearing a hood in southern Illinois, not long after Martin had been gunned down in Florida for doing barely more than this tender-faced young man was. Sitting beside him, I could sense his slenderness; his frame virtually swallowed up the loose-hanging top and threadbare jeans.

Nothing about him threatened me, even though I’m aware that some people use hoods to hide their identity, while up to no good.

Yet sure enough, within ten minutes a porter arrived, roused the youth from his slumber and addressed him. By then I was reading and enveloped in the voice-muting hum that makes train transportation comfortingly attractive. The porter said something to him about “this section.” The youth — likely flashing on the sudden demise of his peer Martin — promptly stood up and headed for the rear. All I know is that it was the coach section of the train, which ostensibly has no limitations on passenger access. And yet here was a young black being deported from it. Was it merely the “threat” of his beardless brown face in his hood, and perhaps his jeans, which might’ve been low-slung?

A young woman, who soon replaced the young black man in the seat beside me, was just a scruffily dressed — wearing a faded peace symbol T-shirt and tattered, low-slung jeans– but she was white and female, and nobody disturbed her. So I ended up in pleasant conversation with her, which I might just as well had with young black man.

Melissa Harris-Perry points out in the April 16 issue of The Nation that “sagging pants laws” in Louisiana, Georgia, Florida and Arkansas now attempt “to legislate the public performance of black bodies by making it illegal to enact particular versions of youth fashion associated with blackness.”

I confess that pants hanging so low that the wearer must shamble along with one hand holding his pants up strike me as somewhat absurd fashion. But is it any more ridiculous than women wobbling around on five-inch spike heels — an extreme fashion that never goes out of style? Both fashions virtually disable their wearer’s mobility as a pedestrian. Both the black youth and the high-heeled woman make easy prey for real muggers of any color or even a hole in the sidewalk that slightly trips them up.

Of course, no one — except a few graying, bushy arm-pitted bra burners — seems to object to high heels, a convention codified and sustained by the patriarchal approval of the sexual allure such contrivances provide, even as they’re demonstrably harmful to women’s feet and body, over time. Not to get too self-righteous: My own libido and conscience struggle with the dichotomy.

But what if every Sex in the City babe strutting in spike heels was forced to wear instead clunky Air Jordans and barely upheld jeans? Would we outlaw the jeans? Unthinkable. Leering patriarchs would tacitly approve of the potential peek at plush tush cleavage. So the sagging pants laws present another one of our cultural hypocrisies.

I mean, anyone of any color can put on a hooded sweatshirt and be a devil or a saint, or more likely just another person passing through a chilly day.

I’m embarrassed to be an American again, underneath the great sense of tragedy that I feel for Martin’s family, for all black people and for all Americans. And before indignant flag wavers respond, know that for decades I’ve written about American culture by striving for a strong sense of inquisitive pride in all things the people of this nation produce to justifiably call it great, in ways that have enriched the world in every sense of the word.

But I’m also honest enough to admit my shame when our gun-toting, might-makes-right, testosterone-loaded adolescent mentality raises its ugly head again. This mentality — that gunned down an utterly innocent young boy — demonstrates the immaturity of our culture: that a man like George Zimmerman can build up an obsession that leads to a supposedly “self defense” killing of a teenager toting nothing but candy on a street. Then the laws ostensibly allowed the killer to go free until a national protest arises and we begin to think about how we behave toward black males as The Other in our society. Martin is akin to the Ishmael outcast Melville identified 160 years ago as an American kind of outsider, typically an immigrant, who felt compelled to go to the sea to escape “the damp, drizzly November in my soul.”

Ishmael saw the sea as a means of flight from society and also from what in himself he understood to be Narcissus, because he could not “grasp the tormenting, mild image he saw in the fountain,” and consequently “plunged into it and was drowned.”

But that same self-image “is the ungraspable phantom of life,” Ishmael concludes, with his redemptive gift for philosophically grappling with the mysteries of existence. He would have us understand that the phantom is a mystery we all share, in our condition of narcissistic self-love, with which the American Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights give us full rein to pursue — individual freedom and self-assertion and self-betterment. Peoples and nations all over the world have since grown to emulate that American freedom of self-regard and self-assertion.

And yet Ishmael sensed the contradictions in the society that proclaimed freedom for everyone, while not according it to many, so he had to flee to the sea. That’s not so easy for anyone. Ishmael’s story in Moby-Dick shows that whaling was a dangerous, often fatal alternative life. And by the turn-of-the-century, W.E.B. Du Bois identified all blacks as Ishmaels — pointedly seen as societal problems because of their skin color. I suspect DuBois might not be shocked, but he would be profoundly chagrined to know how his racial descendants fare in contemporary America.

Oddly enough, when I began this post by trying to first dictate Trayvon Martin’s name on my Dragon dictation system, the computer wrote “unmarked grave.” It’s as if somehow this young dead man is computed as unworthy of a headstone with his name, or of acknowledgement of his premature death. (For me, reading signals of all types is part of the cultural process). How far have we come since the horrendous murder of young black Emmett Till in 1955, which spurred the modern Civil Rights Movement?

In a way we’ve regressed because Till supposedly “provoked” by talking to a Southern white woman. Zimmerman’s deadly response was codified by our recent laws. We certainly won’t fight another Civil War over the abuse or exploitation of African Americans. Reactionary race-based laws or culture will never again face such heroic and tragic resistance. So our national psyche continues with its long, ingrained racial responses to physical presence, style and imagery.

Each of us needs to deal with this racial response within him or herself. As New York Times columnist Brent Staples commented, “Gun laws that allow a community watch volunteer to run around armed are hardly responsible. But Trayvon Martin was killed by a very old idea that will likely take generations of enormous cultural transformation to dislodge.” 1

(Thar he blows! Another damn Moby-Dick sighting again, straight ahead, port side. Abandon ship or proceed.)

I think back to the two main black characters in Moby-Dick. Pip is an African-American cabin boy and Daggoo is a large African harpooner. Pip signifies the vulnerability of a youth like Martin, when he falls out of a whaling boat and is almost abandoned in a shark-infested sea. A cruel sailor had warned the unsteady Pip he’s not worth losing a whale. The experience leaves poor Pip with what we’d probably call now a post-traumatic stress disorder. Yet even monomaniacal Ahab realizes what this young man has endured and takes him under his wing, with surprising paternal tenderness for the remainder of the fateful voyage.

And the mighty Daggoo is framed as the heroic presence his great physical stature and abilities should command. In a famous scene, the ebony harpooner hoists the diminutive third mate Flask on top of his six foot five-inch frame to allow the mate a better view of whales yonder. Melville (as Ishmael) writes:

“But the sight of little Flask mounted upon gigantic Daggoo was yet more curious; for sustaining himself with a cool, indifferent, easy, unthought of, barbaric majesty, noble Negro to every role of the sea harmoniously rolled his fine form. On his broad back, flaxen haired Flask seemed a snowflake. The bearer looked nobler than the rider. Though truly, vivacious, tumultuous, ostentatious little Flask would now and then stamp with impatience; but not one added heave did he thereby give to the Negro’s lordly chest. So have I seen Passion and Vanity stamping the living magnanimous earth, but the earth did not alter her tides and her seasons for that.” *

Why could an observer like Melville so aptly understand, in turn, the human vulnerability and the human majesty of black males in 1851 — yet in 2012, we flounder in according them their due as members of our same democratic country? If the earth does not “alter her times and her seasons” for any man, why should we?

Apparently we do alter our laws because a young man like Martin is not innocent, as Harris-Perry notes with dripping irony. He is guilty of being a “problem,” that is of “being black in presumably restricted public spaces.”

So Martin’s very public being is indicted, as I suspected my seat partner was, rather than anything they actually did.

This existential travesty, of course, flies in the face of our whole judicial philosophy, that a person is innocent until proven guilty. The black man’s being is inherently guilty; how can he ever claim the right of innocence. we have bounty values on their heads in several different ways. Witness the millions spent on incarcerating blacks often for mere marijuana possession.

Conservative commentators noted that Martin had previously been caught with an empty bag containing traces of pot, among other trivial offenses. Here is another cultural hypocrisy: The drug he may have possessed is one that renders a person mellow and even compliant, unlike the belligerence and dangerous aggressiveness of many people intoxicated by alcohol — the drug our culture embraces with unabashed passion.

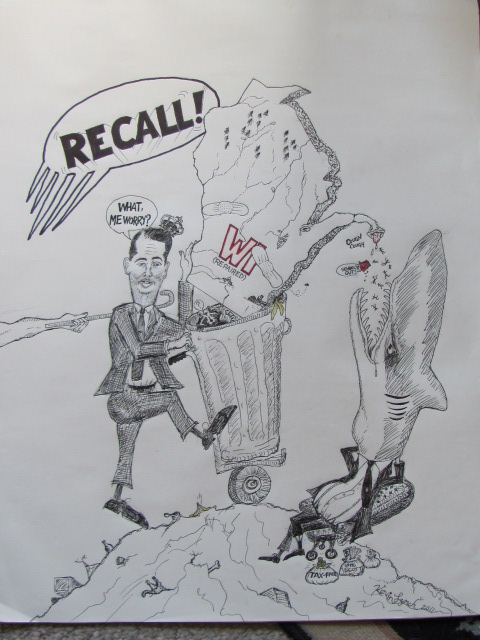

Where do we go from here? Surely we seek justice for Trayvon Martin’s needless death. And with justice we find hopefully some clarity about the cruel absurdity of recent sweeping self-defense legislation – like Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law, or my own state of Wisconsin’s newly imposed “Castle Doctrine” (which recently allowed a man to kill another innocent black youth) — and threaten to shuttle us back to the era of lynching Jim Crow horror.

As Tony Judt has recently noted, echoing Tocqueville from Melville’s era: “The US is more vulnerable to the exploitation of fear for political ends than any other democracy I know.” 2 Judt (a British-born historian) provocatively calls this political demagoguery a “native American fascism.”

Perhaps. Ahab, at his worst, was the archetypal American demagogue in our literature. Yet even he “has his humanities,” as we see above.

Judt sees today’s American “fascism” in right-wing talk show hosts and unapologetic warmongers like Dick Cheney.

Or is it more likely we face our own version of the institutionalized “banality of evil,” which Hannah Arendt warned smug Western society of, during the darkest days of the Third Reich? Surely it is the numbing application of poorly justified laws, as much as fascist fanaticism, that can insidiously infect a democracy that lives in uneasy tension with its legal order.

Today, as vast tides of easily infected electronic info-tainment lull us, true citizens must remain on the lookout for “evil” springing leaks in the American ship (or train?). Otherwise we continue to sink into a democracy waterlogged and infected with cold-blooded, every-man-for-himself survivalism.

We’re still better than that.

— Kevin Lynch

*Moby-Dick Chapter 48 The First Lowering

1. New York Times, op-ed page, April 15, 2012

2. Tony Judt with Timothy Snyder, Thinking the Twentieth Century, Penguin, 2012, 324.

Like this:

Like Loading...