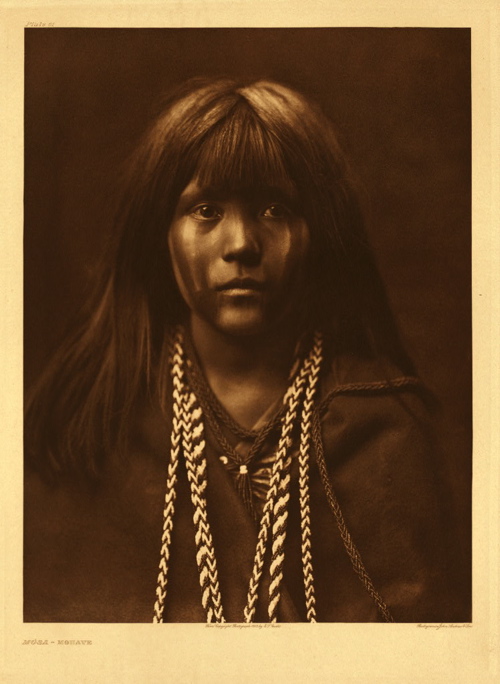

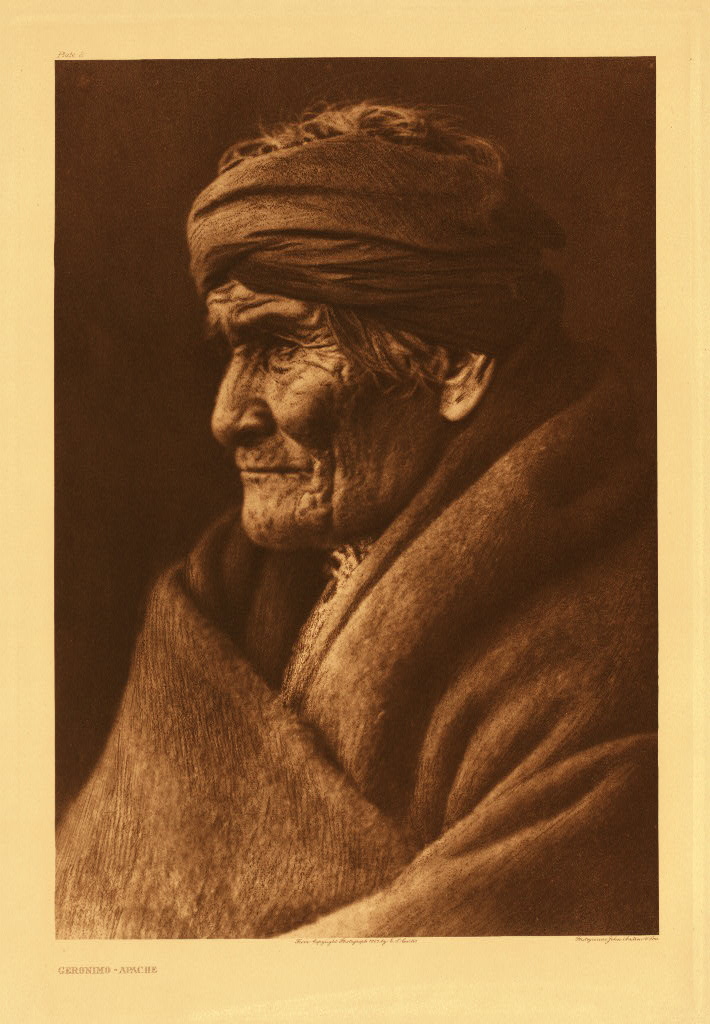

Maggie in (relatively) more courageous days, living in Madison.

Maggie in (relatively) more courageous days, living in Madison.

Authors note: I actually wrote this before Maggie began clearly showing her fatal illness, liver cancer, when she stopped eating for the last two weeks of her life. I now wonder whether her predatory lull, evidenced in the picture below, betrayed her affliction. I still find myself habitually addressing Maggie when I’m at home — and blaming her for things (she was a truly heroic all-purpose scapegoat!) — then realizing she’s gone, a heart pang every time.

By Sir Kevin Edward Lynch a.k.a. Kevernacular

Milwaukee no longer brooded like a Scottish moor. Mists cleared for the city’s too-fleeting zephyrs of summer. A disarmingly intoxicating aura filled the air — lilacs and guttered ephemerals.

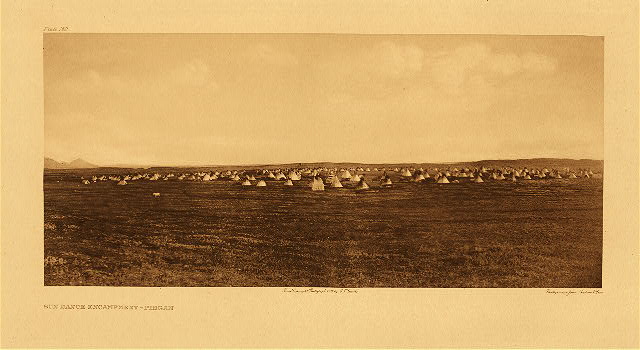

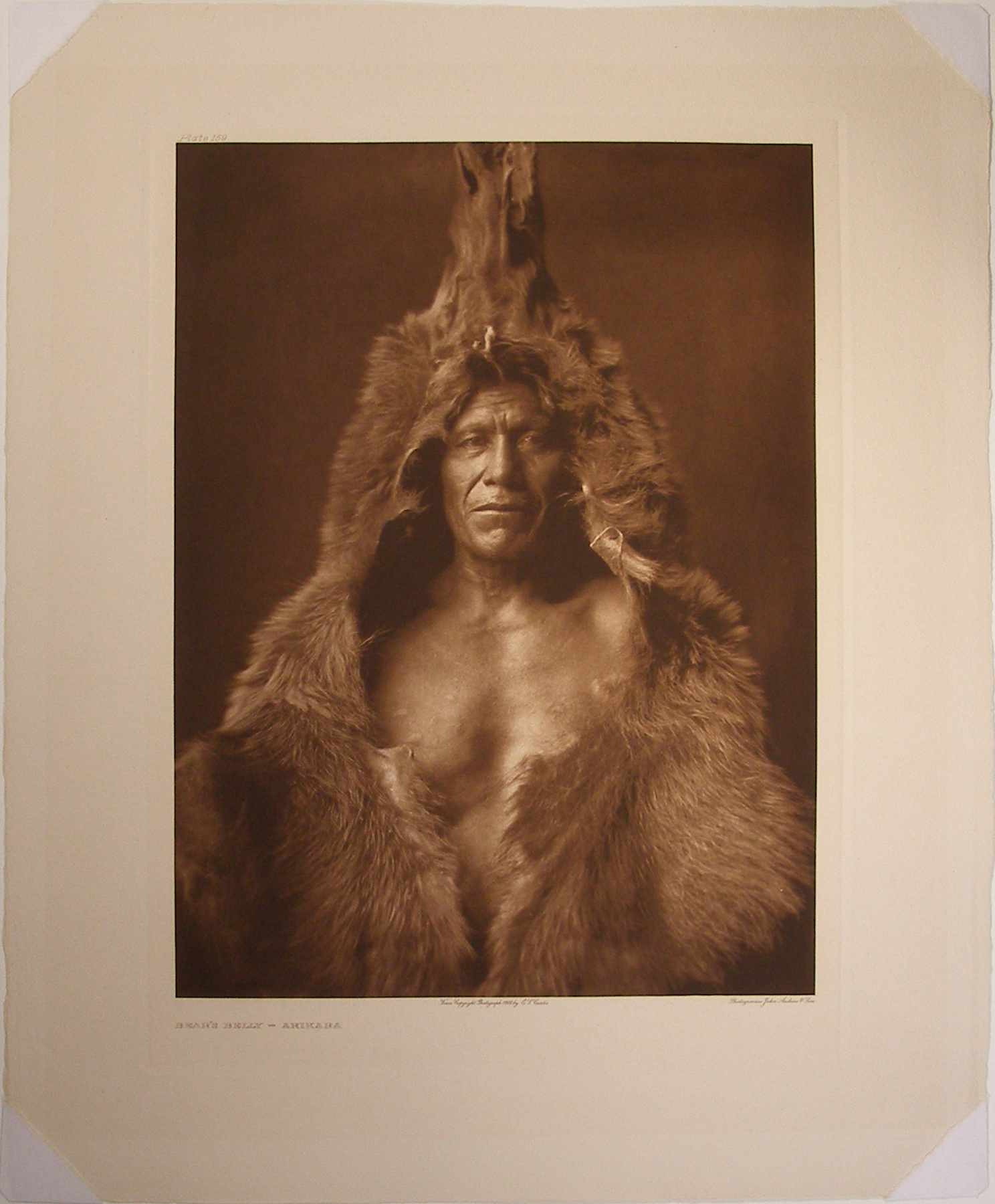

Sherlock Holmes lit his pipe and puffed, but without contentment. A question lingered. Had his intrepid feline Maggie reached advanced middle age? The photo composite below may suggest as much. This supposedly tense face-off transpired for nearly five minutes, with the bird on the TV dish gleefully taunting and mocking Holmes’ dear cat, perched six feet away, safely under his lawn chair.

The entire nerve-wracking time, she twitched hardly a muscle except to peer at her master, through the window.

“Mind-boggling,” whispered Watson.

But appearances were deceiving. Maggie is so intelligent that she knew it was a waste of her precious energy and calories to pursue an antagonist she cannot catch. Good thing, Watson, the bird was no Iago, and Maggie shan’t fall prey to weaknesses of the flesh or romance (though she may love Holmes — in her furry way — but details are unnecessary). Perhaps, as Watson theorizes, she’s now completely embodied her desultory impersonation of Marlene Dietrich as “The Laziest Gal in Town.”

Frankly, as a kitten, she survived horrors — being abandoned at a truck stop, and then being hounded by her next owners’ tail-twiddling toddler. Sherlock’s Magpie has also survived his divorce, a trauma for her as if she were his child. She’s a convicted ex-biter but still hopelessly addicted to Cool Whip, not a pretty picture. You, dear reader, may deduce her supplier. Better to see is her as an adorable, near-Siamese attachment to Holmes’ hip in his easy chair.

So, this tale stands to extol and honor her for remarkable valor and heroism, which wears the deft guise of cowardice, to the eyes of pooh-poohers. Yet I know first-hand, Maggie can pooh-pooh with the best of them. (Her prime aliases: Poopface, Super-Duper Pooper) Clumping litter may cramp her style, at times, but we both appreciate it.

I digress.

“Oh yes, yes,” Watson sputtered, removing his finger from an idle orifice. Holmes worried the man suffers from what they now call ADHD.

To the tale: At the slightest sound, this knowing Margaret perks her ears and — with supercomputer speed — comprehends danger, even if it be a mouse, or me loudly cracking open a can of food that she instantaneously realizes is not for her. She runs like the wind to the nearest, or best, hiding place, in that order.

On a seemingly innocuous day, she reveled noisily amidst her delectable squishy-food meal — when the call for action arose. What had startled her? Holmes quickly theorized that only the Murderers of the Rue Morgue knew, and that they were afoot again. Linger over food? Not our heroine.

She faced the gauntlet. With dazzlingly athletic shake-and-bake jukes, she sidestepped Holmes’ feet, and a suddenly ominous catnip toy or two, and careened past the cat grass – which bent to her swift wind — at the doorway from kitchen to dining room. Newspapers and magazines jumped and fluttered from the parlor rug.

She penetrated her safe haven – a space behind a radiator and bookshelf. Ah, she now had ample time to lick her whiskers clean of precious morsel bits, even if her still-hot path had claimed some droppings. Breathless, she peered out from between the radiator rungs, with a vigilant eye.

Now that’s setting your priorities pragmatically. Safety before savoring. To quote a famous philosopher, I am not making this up.

“Extraordinary, Holmes!” Watson cried.

“Elementary, my dear fellow.”

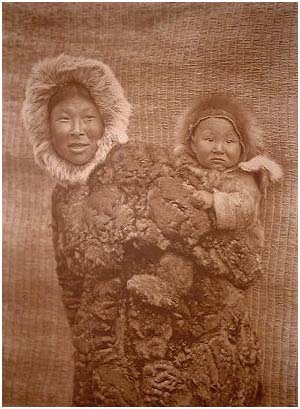

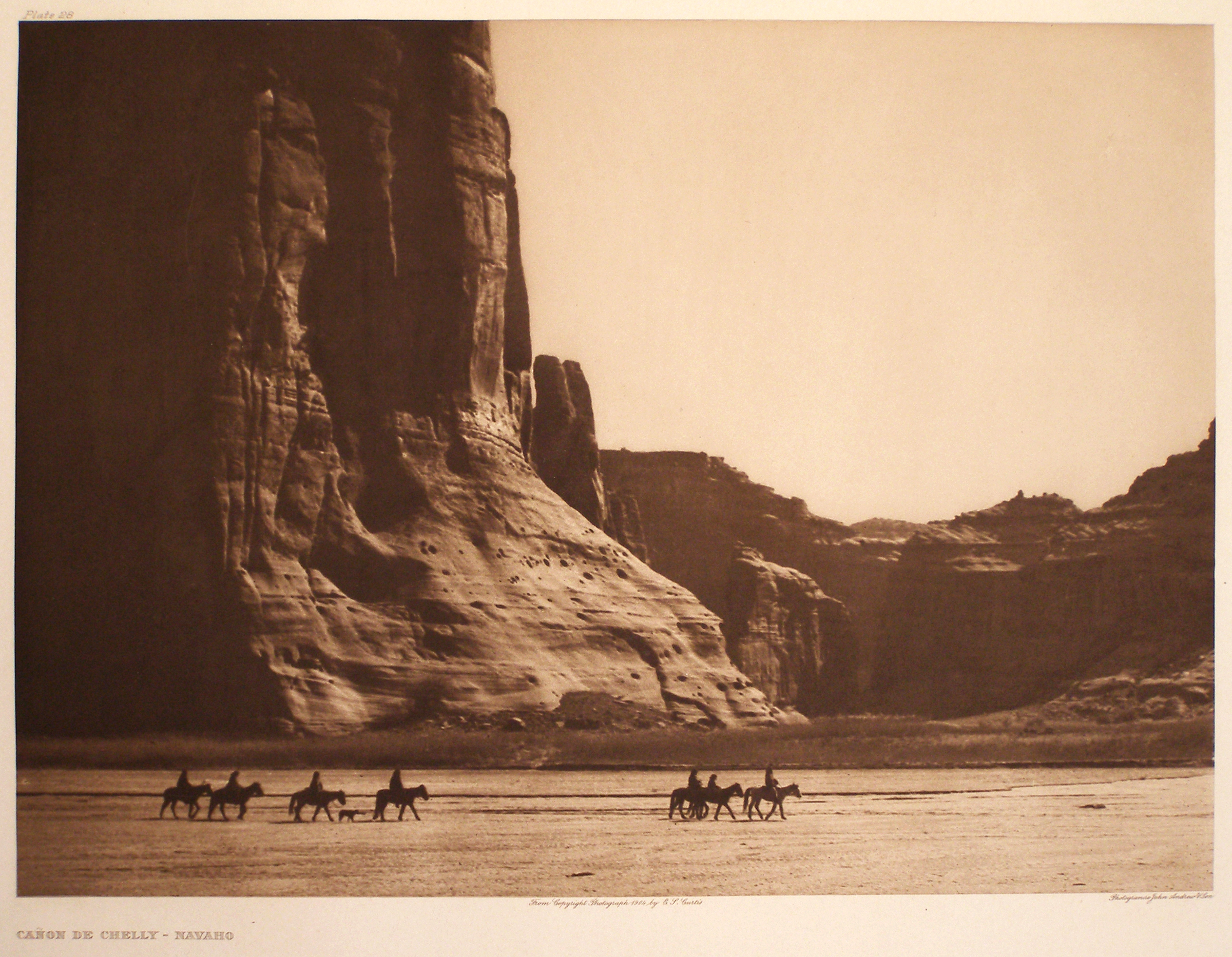

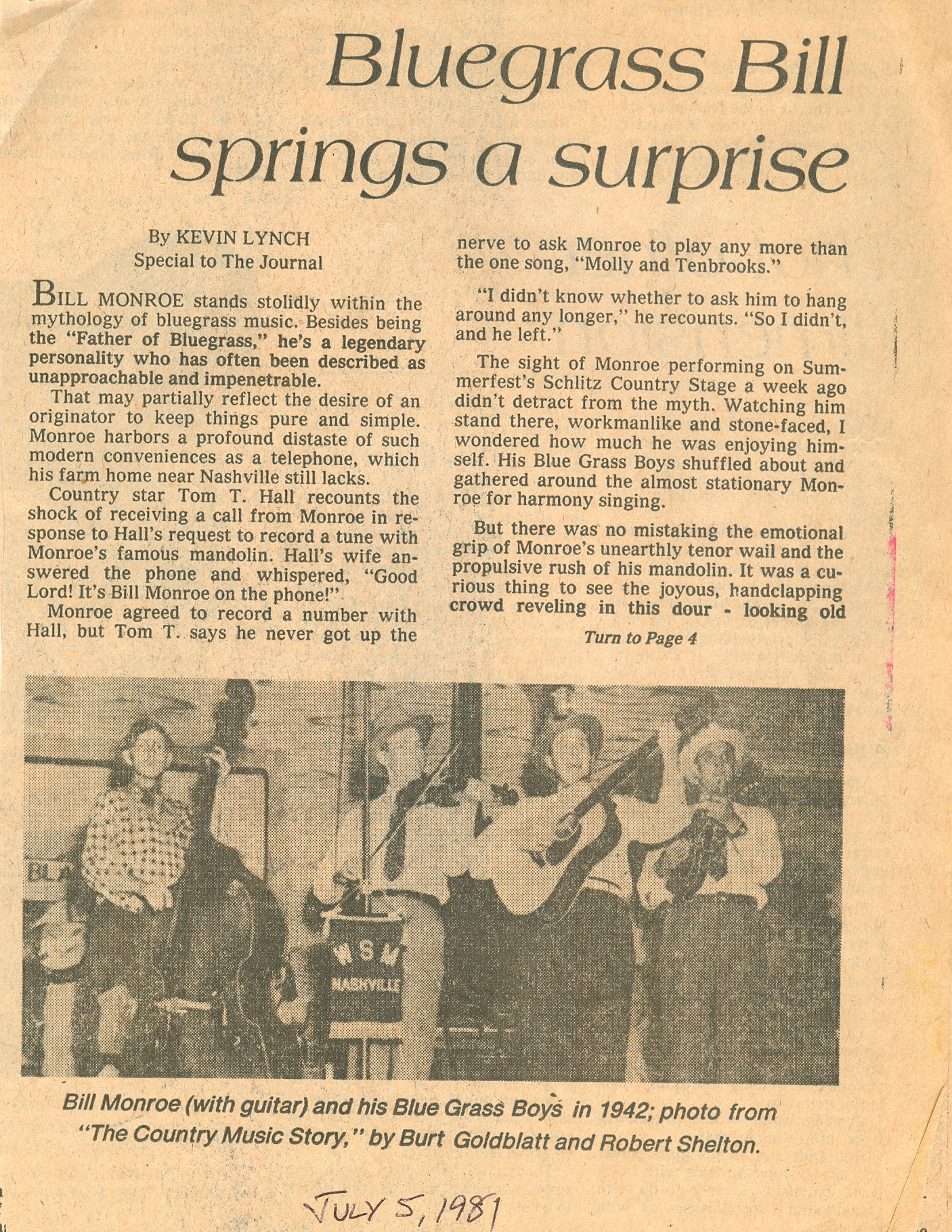

After her adventure, Maggie inspects the fur-raising gauntlet — killer cat grass, insidious toys — she had to pass through to reach safety, to Watson’s astonishment.

After her adventure, Maggie inspects the fur-raising gauntlet — killer cat grass, insidious toys — she had to pass through to reach safety, to Watson’s astonishment.

You see, Maggie the cat educates even Holmes on Safety First. He knows that, in times of threat, that there’s plenty of room for him, too, under the dining room table, or better, deep in the nearby closet, or in her best locale of subterfuge: behind the entertainment center.

This is quite brilliant strategy, because she is nearly hiding in plain view (well, OK, not really). But Holmes can sit looking right in her direction — as can far more threatening TV-watching humanoids — and detect nary a whisker of her, nor her tell-tale tail.

Holmes sometimes thinks he hears her snickering back there. But he grants Maggie her smugness, because she must sacrifice at times. And during this emergency, he confessed to panic — the sheer existential dread of seeing the cat’s canniest survival instincts under seige. So Holmes unceremoniously squeezed in beside her behind the telly, and she curled her tail out of the way — with a frown and attendant complaint — and he scrunched knees to chin. Thus, they hid in that triangular cavity with reasonable discomfort, amid myriad component cords. Of course, he bravely jettisoned his pipe, to make breathing room.

Then, the famous detective’s infallible nose detected a clue. He’d discovered a missing item back there. But Maggie had already taken a fancy to it — a forgotten but fragrant underthingy. Elastic is chewably animated, at least for a short duration.

“Zounds Holmes! Brilliant deduction, finding the underwear, in such dire conditions! Better than Monk!”

“Who’s this, pray tell man?” Holmes retorted. “Monk? Such an obvious pseudonym! And holier than thou, no doubt.”

“Yes, he’s a crackerjack detective I’ve seen on the telly.”

“Irrelevancies!” Holmes thundered. “Here’s what I am told: ‘Holmes, you need to get a hound.’”

“It would keep you active,” his well-meaning former sister-in-law recently counseled. “And she advised, I could meet women while walking a canine, ‘as long as the dog is good-looking.'”

“Pure poppycock! She may have certain points, I concede, clients being scarce lately. But to the latter point: Neither Maggie nor I are deceived by pretty outward appearances. She knows well a bloodthirsty wolf in in sheep’s clothing.”

“Indubitably,” Waston huffed.

“Maggie is ‘good looking’ enough for me, even if for years she’s never ventured outside, beyond the balcony,” Holmes muttered. Let your mind not stray to the gutter, dear reader. T’is not a fit place for man nor beast to do anything — smashed together behind the entertainment center — but breathe and glower at each other in increasing disaffection. There they waited, once again, for the inscrutable terror to pass.

Sitting back he had time for reflection. You see, this cat is our hero, especially in dire times. At least mine. Ergo, Margaret, I forgive you for no longer exhibiting brave – indeed, macho — aggression towards threatening, arrogant birds within reach.

Thus, I will soon solicit on her behalf for a document of certification as:

MADAME MARGARET “MAGGIE” HOLMES, PROFESSIONAL SCARDYCAT, PhD.*

“She will then join us, Watson, in private investigation partnership.”

“Um, her? Partnership?” he fretted. “What’s all this?”

“Elementary…” His swagger rekindled, Holmes finally shouted from the cramped depths: “Cobwebs be damned!”

As he began to climbed out, cruel fate intervened. Suddenly somewhere, in the growing mist beyond, rose the sound of a great hound’s horrendous howl! And I’m told I need a hound! he thought, quaking.

“Heart-stopping!” Watson ejaculated, gripping his chest.

Maggie shuddered at the hound’s accursed wail, but she bravely recovered.

“Meow,” she said sagely.

Hers is the last word. The tale’s told. Almost.

“Hark! To the hideaways!” Holmes boldly commanded.

“You’re in there already, old mate.”

“Good man, Watson! You’re on your own.”

“AAAAAAAOOOUUUUUUUUUUU!!!!”

THE END

*Perpendicular hairs (and run from) Dogs.

Dedicated to the late Maggie Lynch and Sharon J. Lynch, Sherlock Holmes aficionado extraordinaire.

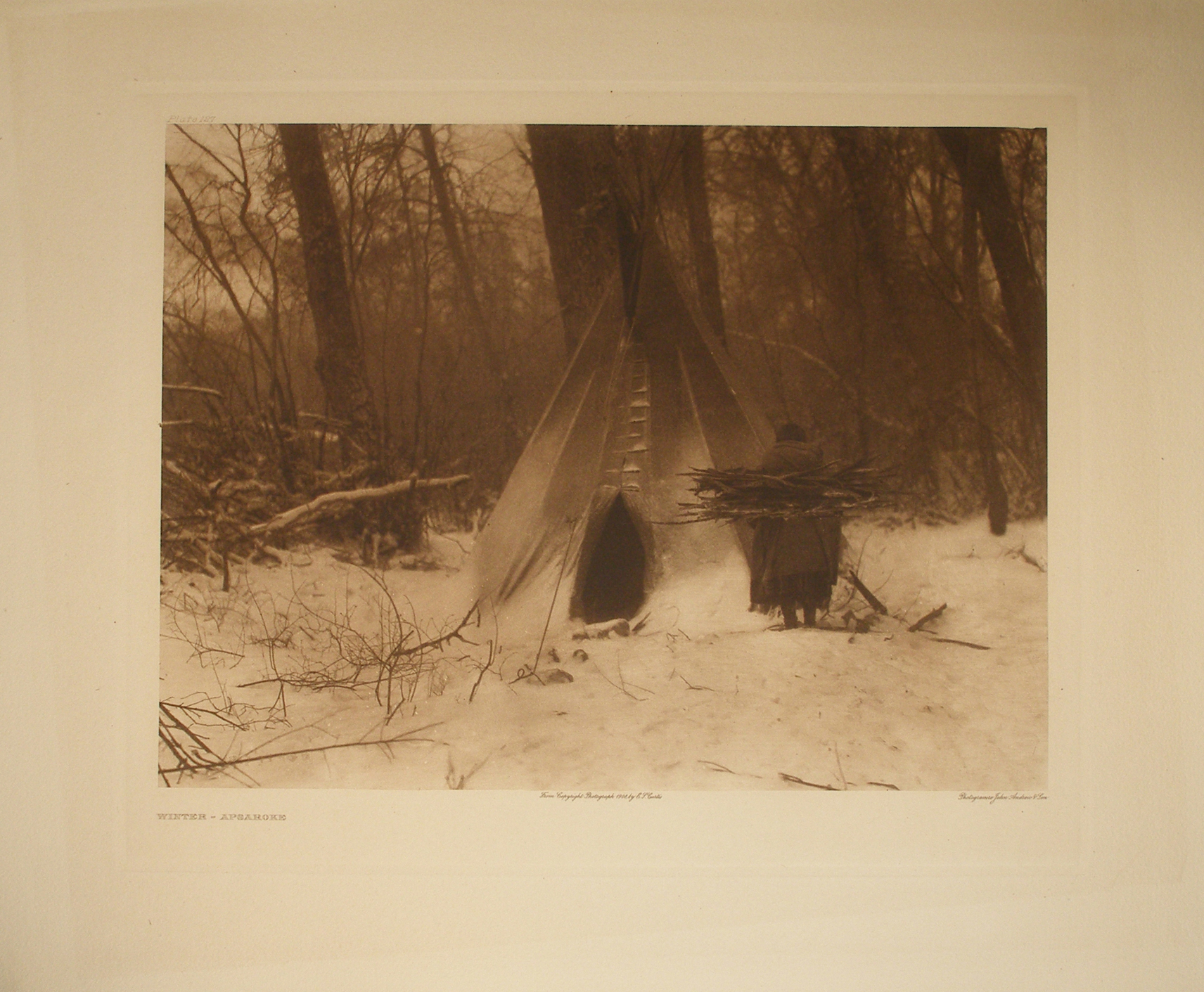

Maggie’s final visit to the balcony, on her last day, August 16, 2013. R.I.P.

Kevernacular’s note:

Kevernacular’s note: