Here’s my two cents worth (and spare change) on the 2012 Grammy Awards. Nope I didn’t hear all the music nominated. How many people did?

But I heard enough to assert my bloggistic opinion, he replied. Here’s an eccentrically broad, personal and biased commentary.

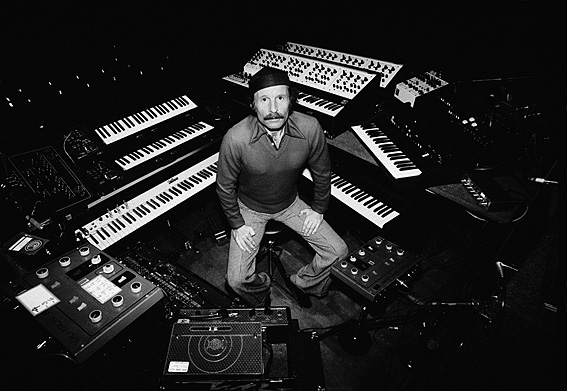

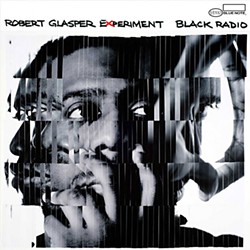

I am glad that the Robert Glasper Experiment won for Best R&B Album. This man showed great creativity, daring, and smart taste. I wrote an article on him for Shepherd Express and as a blog post. The interesting angle was that he played in South Milwaukee, which would’ve been unthinkable for a black artist, borderline suicidal, before the civil rights era.

Here’s that whole story FYI: https://kevernacular.com/?p=844

What’d I liked about Glasper’s album “Black Radio”? The CD delivers not gangsta rapology, but rather a kind of immersion in supple R&B-groove, chill-out “experimentation for meditation.”

It challenged preconceptions. What can you presuppose about an album that seamlessly combines Erykah Badu singing Mongo Santamaria’s Afro-Latin jazz classic “Afro-Blue,” and Lalah Hathaway recasting the cool ecstasy of Sade’s “Cherish the Day”? Add to that “The Consequences of Jealousy” by crossover jazz bassist Meshell Ndegeocello (who plays on the album), David Bowie’s “Letter to Hermione” and Kurt Cobain’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Glasper’s originals, aided by Mos Def, Musiq Soulchild and others, help it all meld. Unlike hardcore hip-hop, Black Radio brims with melodic and harmonic sophistication, more like the hybrids of fellow jazzer Jason Moran.

As for Album of the Year, The Black Keys’ El Camino is strong, scratch-your-grunge-itch stuff but a notch below their previous album Brothers. Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange was right there, but he’ll probably get his, in time (He deservedly won Best Contemporary Urban Album). So I’m not shocked that Mumford and Sons nabbed best album, and happy their Americana category won. It’s a breakthrough vernacular win, like jazzman Herbie Hancock’s best album win with River: The Joni Letters was a few years ago.

However, very good as M&S are, they still strike me as derivative of various American roots-rock bands. Could a bunch of Brits be outdoing all American groups at their own genre? Betraying a tinge of Americanism here, I think not, and might’ve awarded Old Crow Medicine Show’s Carry Me Back or The Avett Brothers’ The Carpenter instead. Or say, Chuck Prophet’s un-nominated Temple Beautiful, an unsentimental and lovingly loosey-goosey roots-rock ode to the seemingly perpetual cultural prism called San Francisco.

I’d love to hear from a Brit reader, or two (and Yanks always). I know, Britain has its own profound roots of traditional and eccentric folk music which contributed to America’s. And the Brits got the deepest grip on American blues in what became the Blues Revival of the ‘60s, though the integrated, Chicago-based Paul Butterfield Blues Band led the way.

However, today Americans are much more aware, appreciative of, and creatively responsive to, their cultural roots.

For example, my actual choice for album of the Year would be This One’s for Him: A Tribute to Guy Clark, a nominee for Best Folk Album. It’s co-produced by Shawn Camp and Tamara Saviano, a Milwaukee native who previously blessed us with the Grammy-nominated Stephen Foster tribute album Beautiful Dreamer.*

Clark’s esteemed peers performed and helped reveal how his song writing has quietly carved a broad swath of insight, peculiarity, tragedy and comedy that epitomizes an essential strain of the American experience. He may be the dean of Texas songwriters, a sun-parched musical bard category that may outshine all others in America. “Desperadoes Waiting for a Train,” “Dublin Blues,” “Hemingway’s Whiskey,” “Stuff that Works,”” The Last Gunfighter Ballad,” “Randall Knife” are among many superb Clark songs still underexposed, yet hidden right in the heart of America. Listen here, to Lyle Lovett, John Prine, Emmylou Harris, Roseanne Cash, Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle, Kris Kristofferson, Willie Nelson, Jerry Jeff Walker, James McMurtry and others.

Along similar lines of preference and argument, the best country album should’ve been Jamey Johnson’s Living for a Song: A Tribute to Hank Cochran, rather than Zac Brown’s Uncaged. Sure Brown’s doing mostly original stuff but he’s got a bit too much rock in his country. My bias is toward traditional or new-trad or alt-country, the latter which Brown is somewhat, but now mainstream country loves him, it seems, the way it now gluts on heavy guitar riffs. Johnson’s curatorial project shed light on one of the most incisively truth-telling songwriters in country history and, like the Clark tribute, had heavyweight acknowledging that with their interpretations, including Nelson, Kristofferson, E. Harris, Merle Haggard, Elvis Costello, Ray Price, Bobby Bare, Allison Krause, George Strait, and Lee Ann Womack etc.

That reminds me of another album, which probably wasn’t nominated because it was released as a combo DVD video as well. That’s We Walked the Line: A Celebration of the Music of Johnny Cash. I won’t list the all-star lineup but do check it out. It climaxed with, for this listener, perhaps the most moving performance of the year: “Highwayman” with Jamey Johnson singing the final verse — which the late Cash sang in the version of the song which The Highwaymen (Cash, Nelson, Kristofferson and Waylon Jennings) recorded in 1985. It’s one of Jimmy Webb’s most poetic, timeless, transcendent and rootsy songs.

Johnson first really got to me with his brief but powerful solo set at the 25th Farm Aid in Milwaukee in October of 2010. He’s a slightly acquired taste, as is Guy Clark. But Johnson’s foghorn-of-the-soul voice and brave commitment to a tradition is as authentic as they come in country these days, among relatively new performers.

OK, radically shifting directions — Country to Classics — but you should never try to pin down Culture Currents. I like messing with your heads a bit. And vernaculars do speak, in many tongues.

Although I haven’t yet heard Michael Tilson Thomas’s recording of John Adams’ Harmonielehre and Short Ride In A Fast Machine, kudos to the Academy for honoring a living composer, if the most obvious one, for Best Classical Orchestral Recording. The former piece achieves the improbable: merging minimalism with its antithesis, Arnold Schoenberg, thus opening a deep throbbing vein that pulses with dark duende and humanity intensely magnified.

Yet the San Francisco Symphony program seems slight compared to Simon Rattle’s 1994 recording of these works, which also includes “The Chairman Dances” and other Adams pieces (full disclosure: a relative of mine is in the SF orchestra, so I’m avoiding favoritism here.).

And Thomas beat out a strong reading of Mahler’s First Symphony by Ivan Fischer and the Budapest Radio Orchestra. Hearing this ever-mighty Mahler – as he echoes through the vast and haunted crevasse between Romanticism and modernism — reminds one of how minimalism, liberating as it can be, so often is too much of not enough.

I say, Mahler! by a nose, famously aquiline. (Look for a brand-new recording of Mahler’s First by Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra music director Edo du Waart in the 2013 Grammy running, albeit with his other band, The Royal Flemish Philharmonic.)

In Best Opera Recording, James Levine and his Wagnerian horde predictably rolled over the competition with his Der Ring cycle, like the Third Reich steamrolling Poland (a strange role for Levine). But smashed in that blitzkrieg was Alban Berg’s Lulu, an unforgettably entrancing Lulu of a high-modernist opera, bravely led by Michael Boder, and Vladimir Jurowski’s take on Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress.

Best Jazz Vocal Album went to Esperanza Spalding’s Radio Music Society. I still think Ms. Spalding is a better musician and conceptualizer than a singer. She should not have beaten out Kurt Elling’s 619 Broadway: The Brills Building Project (tributing the Gershwins, Kerns, Porters, et al) or Luciana Souza’s The Book of Chet (as in Baker). But Spalding is ambitious and definitely the jazz flavor (dare I say sweetheart?) of the year. And she’s got game and I do love her world-class ‘fro.

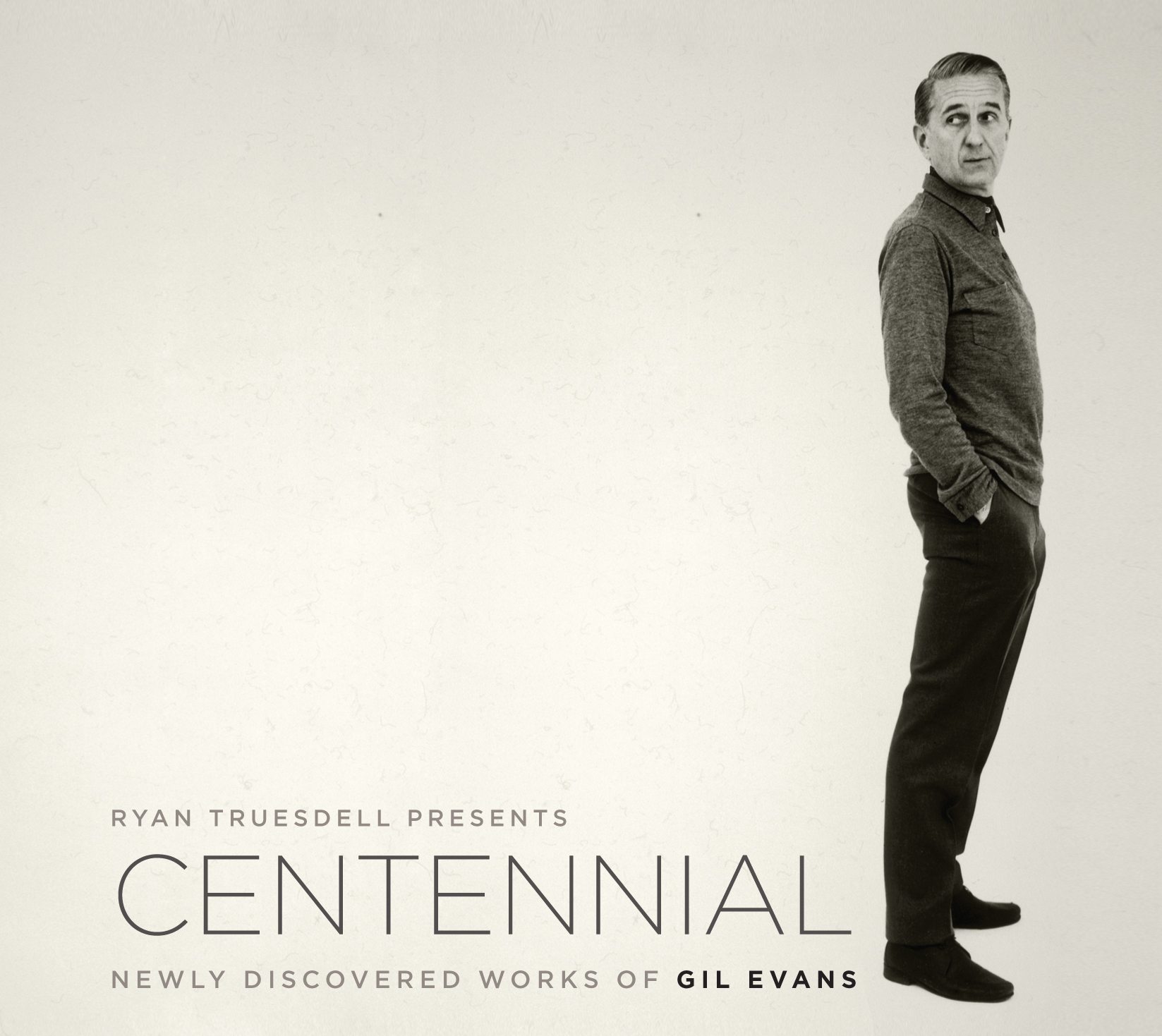

I’d also say that Arturo Sandoval’s admirable For Diz: Every Day I Think of You won Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album with more flash than my choice. The Gil Evans Project proved that nothing can replace modern jazz’s greatest arranger, but leader Ryan Truesdell’s magnificent effort on Centennial: Newly Discovered Works of Gil Evans, unearthed glittering new treasures from the late Evans’ legacy. And although The Evans Project album’s How About You achieves a splendid swing, it hardly should’ve won Best Instrumental Arrangement over the same album’s endlessly beguiling Barbara Song or the transporting Pubjab, neither of which was nominated. A very retro — borderline moldy fig — choice for arrangement. I blogged on this album, too. https://kevernacular.com/?p=702

I also would have put vibes player Joe Locke and tenor saxophonist Donny McCaslin right in the running for Best Improvised Jazz Solo on Centennial‘s “Waltz/Variation on the Misery/So Long.” Locke delivers gleaming substance on several of the album’s major pieces. Chick Corea and Gary Burton, who have closets full of awards and accolades, won for Hot House, vintage bebop updated. That’s perpetually hip, but also comparatively retro.

Somebody please swivel around the Academy jazz voters, so they face forward. Do you question that assertion, given my promoting of various tribute albums of, say, trad country?

“Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes.” Well, Walt Whitman did. Culture Currents tries to. You go where the best music takes you.

Speaking of philosophical assertions, for a broad-brush but insightful commentary on the Grammys, I recommend NoDepression.com editor Kim Reuhl’s recent ruminations. Noting the Grammies are a sort of Music Industry/Recording Marketing love fest, she says that, even if they have no vote, the worldwide community of listeners is ultimately what counts. Listeners and the role music plays in life:

“Here’s the thing. Music is so important. Next to painting, storytelling, and dance, it’s one of the best vehicles we have for destroying fear, for confronting our best and worst selves, for letting love blow us wide open. At its best, music is where we interact with the most vulnerable bits of our humanity. It’s where we admit everything to each other, to strangers, to ourselves, in a way that is safe and embracing, and promising, and full of hope. At the end of a song, we can close the figurative container and go back to Life, renewed.”

Rave on, Kim Reuhl, rave on.

Here’s the URL to her whole piece:http://www.nodepression.com/profiles/blogs/art-the-artists-freedom-and-the-grammys

“Portrait of the Artist” by Rembrandt ca. 1665. Image courtesy wikipaintings.org.

“Portrait of the Artist” by Rembrandt ca. 1665. Image courtesy wikipaintings.org.