Cafe Carpe has been a labor of love, and a family endeavor for co-owners Kitty Welch and Bill Camplin (center) and their offspring, Savannah Camplin (left) and Satchel Paige Welch (top).

This is an updated version of an article originally published in July, 2010 in YourNews.com, Madison WI edition.

FORT ATKINSON – If the carp ain’t bitin’ folk here just start writin’ – and singin’ and pickin’. Actually locals have caught white bass lately in the Rock River, beside the café named for the infamous scavenger that slouches toward river bottoms. Does the Café Carpe, a rootsy music mecca, befit its homely name?

The music club-restaurant sometime scrounges financially but it basks in the harmonious rays of its self-generated musical sunlight. Truth is, the Carpe’s lovingly tended riverside rain garden, situated just below a screened-in porch, symbolizes the place as well as anything – with its dense growth of eccentric vegetation and a corner configured with small boulders and logs where co-owner Bill Camplin stirs up campfire sing-alongs and the spirit of big sky country.

The gifted singer-songwriter and his partner Kitty Welch began to feed the region’s cultural wellspring when they bought this house on the Rock in 1985. At the time, the tides were rising for roots music and they’ve rode ‘em ever since, through hell and high water. The Carpe still holds steady for hard-scrabble blues bashers and song hawkers who trudge the dusty highways of America’s great, broad hobbled back.

With its weather-beaten wooden sign hanging over the door, the Carpe lies all too easily beneath the suspicion of many locals and regionals. They often can’t sense the level of intensity, ingenuity and engagement radiating from the cozy corner stage in a rigorously enclosed listening space behind the restaurant-bar.

Cafe Carpe on Main Street in Fort Atkinson

Each Thursday through Saturday, an array of local, regional and traveling storytellers and musicians grace this clean, well-lighted place – a Heartland beacon where the hearty literary spirit of American vernacular music burns.

Hemingway is easy enough to imagine at the bar, gradually being stirred by the Carpe’s rough-hewn majesty as a safe haven for musical wordsmiths.

No doubt, the geographic heart of Wisconsin’s roots music voice breathes from the backroom of the sunlit cafe on 18 S. Water Street, a half a block off Main.

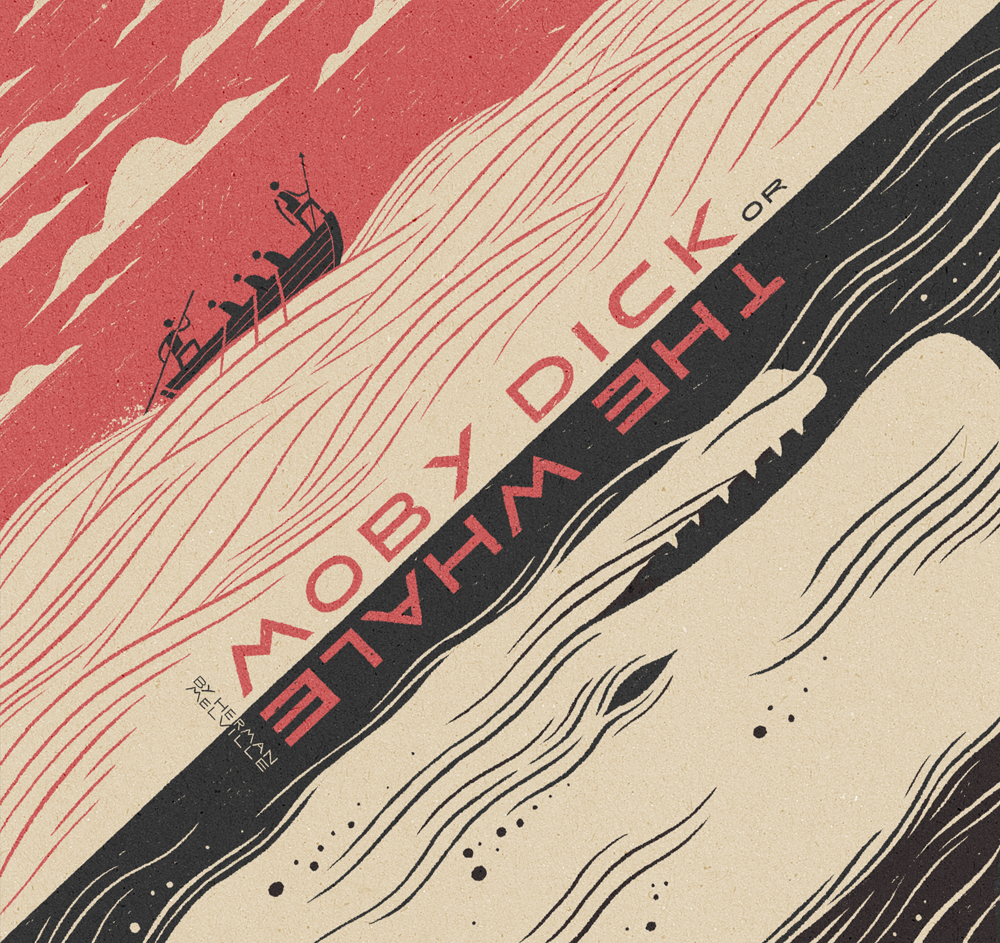

Many stripes of musical verifiers here signify a new sort of American Renaissance afoot. No towering Melvilles or Whitmans perhaps, but something else, far more multitudinous, like myriad new hybrids of wildflower appearing along highways and meadows — fresh affirmation of Melville’s fearless confiding: “Believe me friends, that Shakespeares are this day being born on the banks of the Ohio.”

He wrote that in his famous American identity-marking essay Hawthorne and his Mosses, in July 1850. One hundred and sixty summers later, on the mossy banks of the Rock, you’ll find bards brandishing guitars mandolins and sharply drawn metaphors – and a few being born, in effect.

The Carpe has spawned, in its peculiar ways, some superb singer-songwriters: nurturing homebody Camplin, Milwaukeean Peter Mulvey and Jeffrey Foucault who grew up in Fort – and one year “home-schooled” Camplin’s son Satchel — for beer flow at the Carpe. Mulvey and Foucault have forged impressive touring and recording careers, and an even younger breed of “baby carpes”: Hayward Williams, Josh Harty, Blake Thomas and Satchel Paige Welch. Foucault will play the Carpe on June 20 (2014).

Cafe Carpe was artistically formative for singer-songwriter Jeffrey Foucault, who performs here with his singer-songwriter wife Kris Delmhorst in a club in Pennsylvania. Courtesy www.pollstar.com

Once America’s great writers spun vast fields of poetic grass or poured Vesuvius craters of ink into great sea novels. Today they just as often let dazzling lines fly from their lips like hungry fish leaping for a firefly and emerging with a whale of an inspiration – a curious illusion possibly effected by the refraction of river water and the Carpe’s hearty port wines.

Their profile slowly rises. The place maintains a vibrant website www.cafecarpe.net, with a performance schedule chock full of artist bios by the relentlessly witty Camplin. Accordingly, his own live performances invariably blend tangential drollery; uncanny, falsetto-haunted crooning and impeccable taste in roots songs, especially his Dylan.

A recent Camplin performance ranged from his poignant character sketch Old Man, Where Are You Sleeping Tonight? to Townes Van Zandt’s dusty, picaresque Pancho and Lefty, where he called up the two young set openers, Harty and Thomas, for a lovely three-part harmony, a scene typifying the Carpe’s nurturing artistic camaraderie.

The joint also draws diners nightly for trademark homemade pizza and jambalaya. There’s social lubrication available and sometimes a lonely local barfly nursing a tragedy in the bottom of a beer.

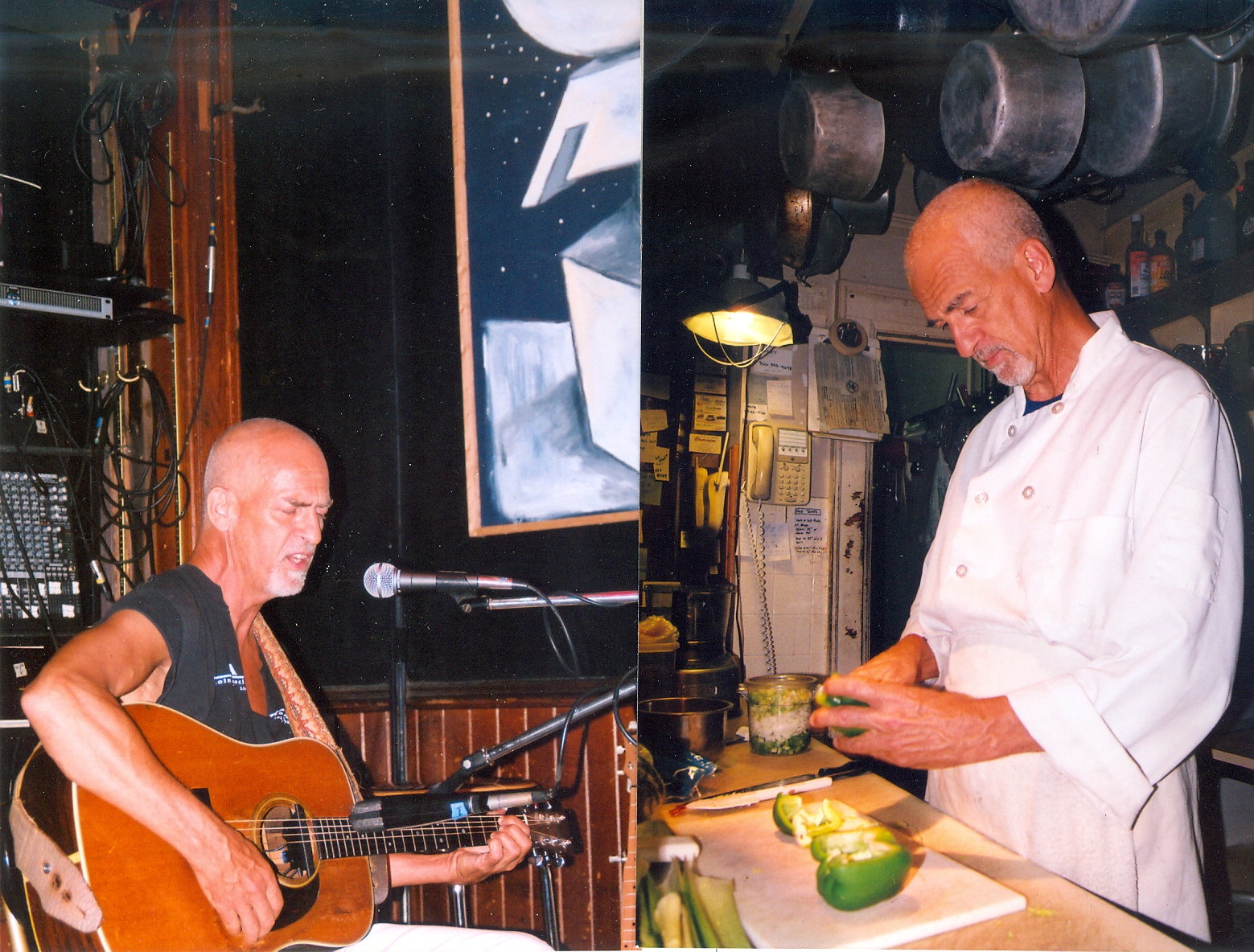

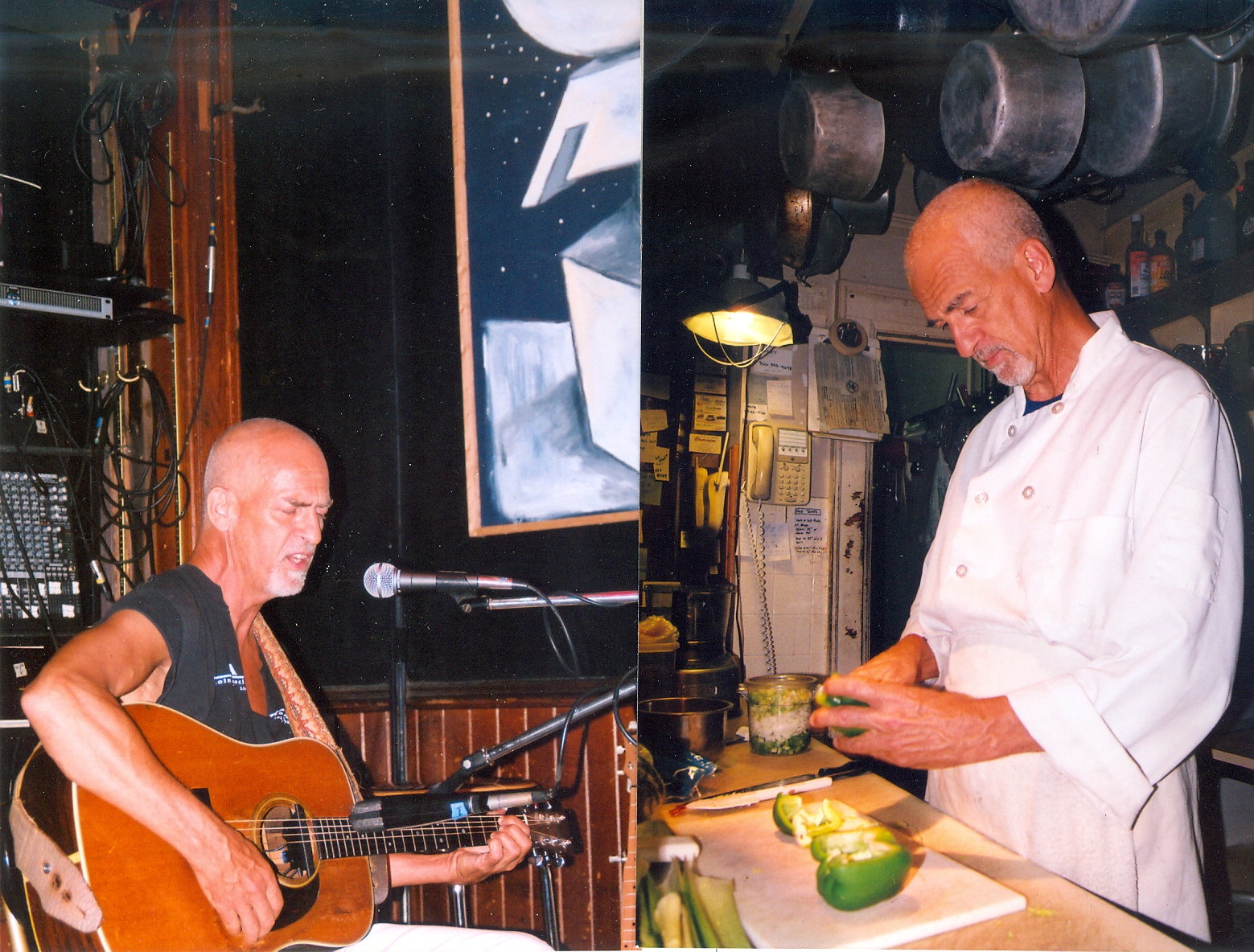

Cafe Carpe co-owner Bill Camplin is almost as handy in the kitchen as he is on the bandstand.

Reality check: some nights the performers slightly outnumber the listeners. This partly reflects a decades-old cultural assumption – despite Bob Dylan’s long preeminence as America’s greatest living poet – that “folk music” is a sentimental strain of button-down kitsch, a la the Kingston Trio. Consider Gene Santoro’s chapter on “the folk revival” in his excellent 2004 book Highway 61 Revisited: The Tangled Roots of American Jazz, Blues, Rock and Country Music. He describes how blues folk rabble-rouser Dave Van Ronk deconstructed Santoro’s musical expectations of folk when he first heard him in a Greenwich Village club in the 60s.

“Two things I knew even as I was alternately squirming and transfixed through Van Ronk’s show: he was a hellacious guitar picker, a real – and therefore in pop and folk circles rare musician and he was the only white guy I ‘d ever heard whose singing showed that he truly understood Louis Armstrong and Muddy Waters,” wrote Santoro. “When he roared he felt like a hurricane blast shaking that little club.”

Most serious folk musicians have actually strove for Van Ronk’s standard ever since, and many white folksters reveal understanding, in their bones, of the great black fathers of american roots music. Dylan as much as anyone. Today’s folk artists seem to be real musicians for their purposes, while working to raise the bar with good ol’ American competitiveness which nice, pinko communal values still can’t obliterate.

As Armstrong once said: “All music is folk music. Horses don’t sing.”

Camplin has an interesting philosophical perspective on Café Carpe, which he calls a “failure” after 24 years of drawing a deep array of singer-songwriters touring which probably wouldn’t have happened if he hadn’t opened the joint when the roots movement first gained traction. Yet he rues the fact he can’t dependably fill the 70-seat music space for traveling performers to make it worth the trip.

Still, they built it and they did come, and that’s where he admits laboriously fitful success.

“There oughta be several places like this in Madison and five in Milwaukee,” Camplin asserts. There’s no comparable venue in Wisconsin, though Milwaukee’s Shank Hall and Linneman’s Inn and Madison’s High Noon Saloon and Mother Fool’s Coffeehouse all add roots musics but none with the frequency, or focused quality experience of listening sequestered from the bar or plying waiters.

Chicago’s fabled Old Town of Folk Music also lends the music but not the intimacy. This remains part of the challenge of this movement, the paucity of small club owners willing to consistently commit to non-commercial, largely acoustic music. But Camplin’s “No Depression” philosophy copes with disappointment serviceably for now.

“I’m enough of a Republican to think that music shouldn’t depend on grants,” he says wrly.

Interpret his political colors from his new unrecorded song “The Fat Cats (are takin it easy),” part of Camplin’s forthcoming album Understory, a rollicking ditty which has had crowds buzzing of late. He’s a small businessman-artist with a big voice and artistic integrity. He expects a standard of excellence and commitment from artists.

“I think more musicians should try to build rapport with audiences rather than doing one-night stands,” he says. “The old jazz players knew how to do that.”

Cultural time may be on Camplin’s side, to see renovated small-town venues like the Stoughton Opera House, which a few years ago developed a full season of largely roots-style performance events that has given Madison’s Overture Center a run for its money. The names Stoughton has hosted recently positively glitter: Dr. Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys, The Del McCoury Band, Iris Dement, Richard Thompson, Arlo Guthrie, Richie Havens, The Cowboy Junkies, Rickie Lee Jones, John Sebastian, Leo Kottke, Dan Tyminski, the Smothers Brothers and the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Gillian Welch plays at Stoughton on July 3 (2014) in a sold-out show.

The fabulously refurbished opera house has whizzed past Overture and the Wisconsin Union Theater as the hippest fancy night out in South-central Wisconsin. The revered Stanley and Tyminski – who dubbed actor George Clooney’s singing on the soundtrack to O Brother Where Art Though Thou? were central to the success of that Coen Brothers’ movie, which singlehandedly sparked the bluegrass revival in 2000. Frankly, roots music lovers never had it so good.

This all bodes well for Fort Atkinson’s nobly bottom-feeding river cafe, but not if people simply opt for chandelier shows and neglect the roadhouses that begat each of those big names. Camplin and Welch have persevered with alt-business savvy. Camplin himself is almost as skilled in the Carpe’s kitchen and spent all of a recent Saturday garbed in a white chef’s frock, as he sliced fixings for a scrumptious (I attest) jambalaya and dragged huge, smoking-hot pans of chow out of the ovens.

Veggie chopping is dicey work for a guitarist, he admits. A few Camplin fingertips may have nestled in among the jambalaya ham bits over the years, he half-jokes. The restaurant also has a stable of able cooks, including Welch, and the couple has succeeded well enough to extensively remodel their home above the venue, and add the faintly funky luxuries of a riverfront patio and rain garden.

Their son Satchel Paige Welch, embodies the new breed of musical bard. His name, from the legendary black baseball hurler, bespeaks Camplin’s passion for the American pastime, particularly its dusky heroes like Henry Aaron, who’ll always be a Milwaukee Brave in these parts.

Maybe Paige will be the next Shakespeare born on the banks of an American river. Okay, he was two when his parents moved to Fort Atkinson but Rock River life and culture runs in Satchel’s currents.

He’s patiently cultivating his muse and craft, writing a perfect guitar riff for a Foucault refrain, adding his vocals, bass and production skills to his father’s latest CD and building on the promise of his debut CD at age 18.

This thoughtful, slightly angst-ridden young man bridles at those who persist in asking why he’s still at home, what he’s up to. (He’s since moved to Nashville and is music producing, including his dad’s upcoming CD) His situation mirrors others of a generation that, in hard economic times, has begun investigating older forms by making the past their own, like his friend Alex Ramsey of the excellent alt-country folk band The Pines, who also lives at home biding his talent. Ramsey’s father Bo added quietly dazzling resonator guitar to Foucault’s Ghost Repeater CD.

These are also children of better-know entities like the 30-year-old public television phenomenon Austin City Limits, the mushrooming annual South by Southwest music conference, also in Austin, Texas, a profusion of roots music festivals nationwide and the Americana Music Association.

Old Crow Medicine Show, Gillian Welch, Norah Jones, Justin Townes Earle, Hayes Carll, Josh Ritter, Tift Merritt, Diana Jones and recent Oscar-winner Ryan Bingham are a few of the big young talents on the roots scene. Such young talent represents the fresh warm crust of a deep dish pie of performing talent many years in the baking, and brimming with the mature fruit of previous Carpe performers, including Peter and Lou Berryman, Greg Brown, Rory Block, Ronny Cox (a singer songwriter best known as a film actor (Deliverance, Bound for Glory), Cliff Eberhardt, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Sleepy LaBeef, Country Joe McDonald, Geoff Muldaur, Utah Phillips, Jim Post, John Renbourn, Dave Van Ronk, Claudia Schmidt, John Stewart, Eric Taylor, Tony Trischka, Dar Williams, Robin and Linda Williams, among others. The Carpe has also hosted a reading by legendary author Ursula K. LeGuin and a political stump speech by legendary songwriter Carole King.

But don’t sons and daughters typically reject parent’s values and aesthetics? In fact, a whole generation of musical artists is asserting identity on their own roots-related terms, shaping new styles from re-thatched sprigs of the past. Such identity factors may account for more than any rekindling of the idealism their parents professed to change the world with, Paige says.

As he puts it: “I’m trying to globalize.” Then you hear his own generational idealism, sans transformative notions: “Why speak to one culture when you can speak to all cultures? If I’ve developed my style or voice right, it’s really important that I communicate with an 80-year-old as much as I do to an 18-year-old.” He slightly brings to mind the ambitiously the real, old Satchel Paige, who made America love him on his own terms, mythical or not.

In The Roots of Romanticism, philosopher Isaiah Berlin wrote that the profoundly influential Germanic Romantic movement, which championed folk music and dance, asserted that culture involves “an infinite striving forward on the part of reality.” Folk art communicated the growth of human groups for which “organic, botanical and other biological metaphors were more suitable” than “chemical and mathematical metaphors of 17th century French popularizers of science.”

“Truth is like a pearl,” Foucault sings in the song City Flower. Increasingly creative young Americans like Satchel Paige, following his namesake, aim for the outside corner of destiny, mixing pearls with their knuckleballs.

_________________

Unless otherwise indicated, all photos by Kevin Lynch

- Highway 61 Revisited: The Tangled Roots of American Jazz, Blues, Rock and Country Music. Gene Santoro, Oxford University Press 1994 p 104

- The Roots of Romanticism Isaiah Berlin, Princeton University Press, 1999, p 101

- Ibid pp. 59-61.

Like this:

Like Loading...

A tugboat pulls the Charles W. Morgan out to sea for a rare historical informational festival tour about whaling along the eastern seaboard.

A tugboat pulls the Charles W. Morgan out to sea for a rare historical informational festival tour about whaling along the eastern seaboard.

Drummer-composer Devin Drobka Courtesy wmse.org.

Drummer-composer Devin Drobka Courtesy wmse.org.  The Bad Plus: The Rite of Spring (Masterworks)

The Bad Plus: The Rite of Spring (Masterworks) The Bad Plus perform “The Rite of Spring” live in Boston. From left, pianist Ethan Iverson, bassist Reid Anderson, drummer Dave King. Courtesy bostonglobe.com.

The Bad Plus perform “The Rite of Spring” live in Boston. From left, pianist Ethan Iverson, bassist Reid Anderson, drummer Dave King. Courtesy bostonglobe.com. Russ Johnson — Meeting Point (Relay Recordings) CD review

Russ Johnson — Meeting Point (Relay Recordings) CD review  Johnson has done as much as any recent musician to keep Dolphy’s legacy alive, having performed the music from Dolphy’s classic Out to Lunch album at a special event honoring Dolphy, which included the unveiling of a bronze statue of the great jazz wind player at LeMoyne College in 2010 (Most of Johnson’s Dolphy interpretations are readily available on YouTube).

Johnson has done as much as any recent musician to keep Dolphy’s legacy alive, having performed the music from Dolphy’s classic Out to Lunch album at a special event honoring Dolphy, which included the unveiling of a bronze statue of the great jazz wind player at LeMoyne College in 2010 (Most of Johnson’s Dolphy interpretations are readily available on YouTube).

Kevernacular (Kevin Lynch) received a “gold award” plaque for the Culture Currents blog Friday at the Milwaukee Press Club awards dinner. To quote Sen. Elizabeth Warren, “I never dreamed I would be a blond.” Photo by Ann K. Peterson

Kevernacular (Kevin Lynch) received a “gold award” plaque for the Culture Currents blog Friday at the Milwaukee Press Club awards dinner. To quote Sen. Elizabeth Warren, “I never dreamed I would be a blond.” Photo by Ann K. Peterson

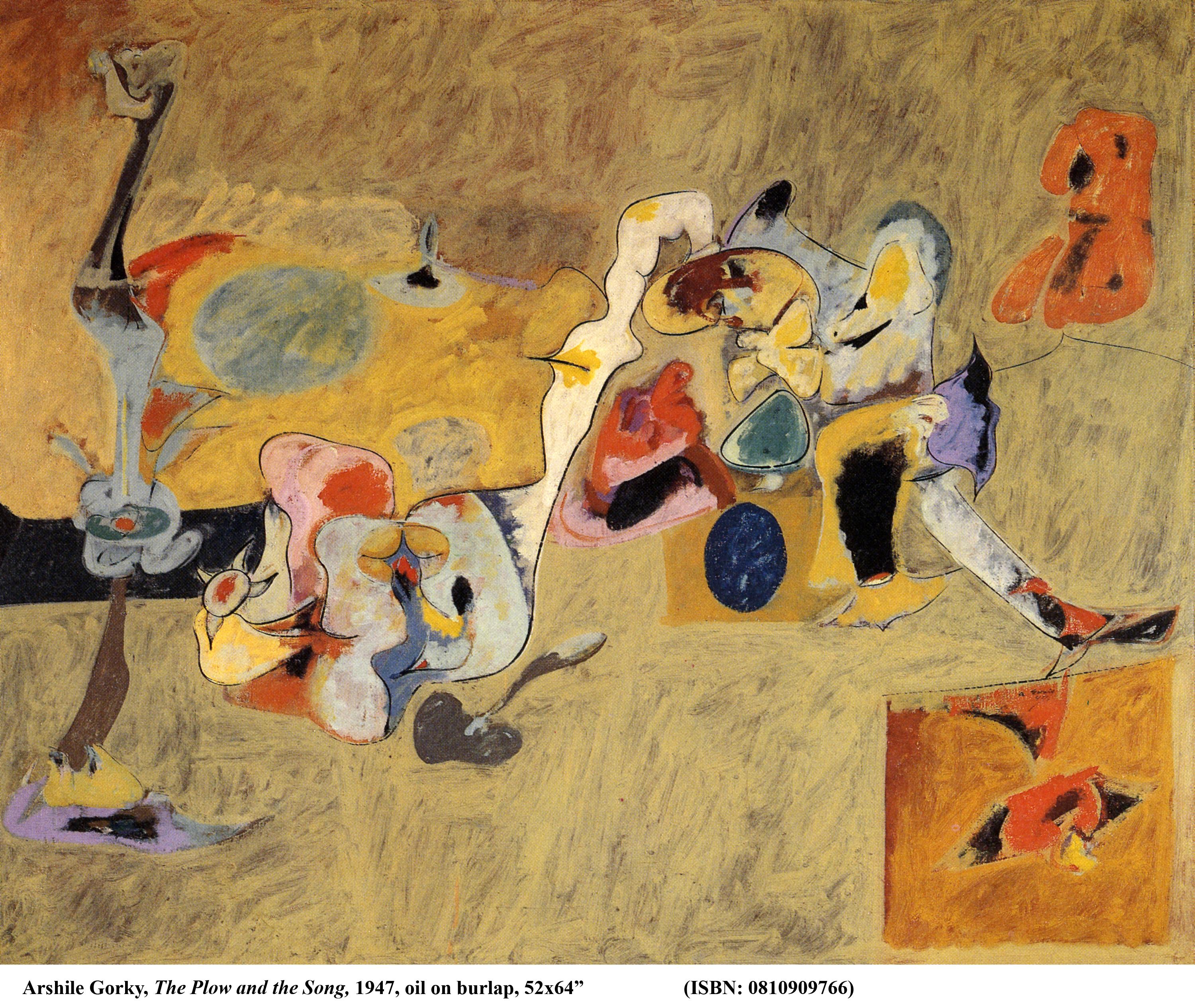

Arshile Gorky “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” oil on canvas 1944. These two paintings are superb examples of Gorky’s great skill at hanging a composition along the formal undergrid of The Golden Mean. The proportional ideal allowed Gorky guidance as he explored the boundaries of surrealism and abstraction. Much of this best work derives from his intensely close observations of nature. In one famous instance, Gorky laid face-down in a garden, opened his eyes and took in the visual sensation of this extreme perspective. In this manner, one can begin to understand the relationship between acquired impressions and an artist’s abstractions.

Arshile Gorky “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” oil on canvas 1944. These two paintings are superb examples of Gorky’s great skill at hanging a composition along the formal undergrid of The Golden Mean. The proportional ideal allowed Gorky guidance as he explored the boundaries of surrealism and abstraction. Much of this best work derives from his intensely close observations of nature. In one famous instance, Gorky laid face-down in a garden, opened his eyes and took in the visual sensation of this extreme perspective. In this manner, one can begin to understand the relationship between acquired impressions and an artist’s abstractions.

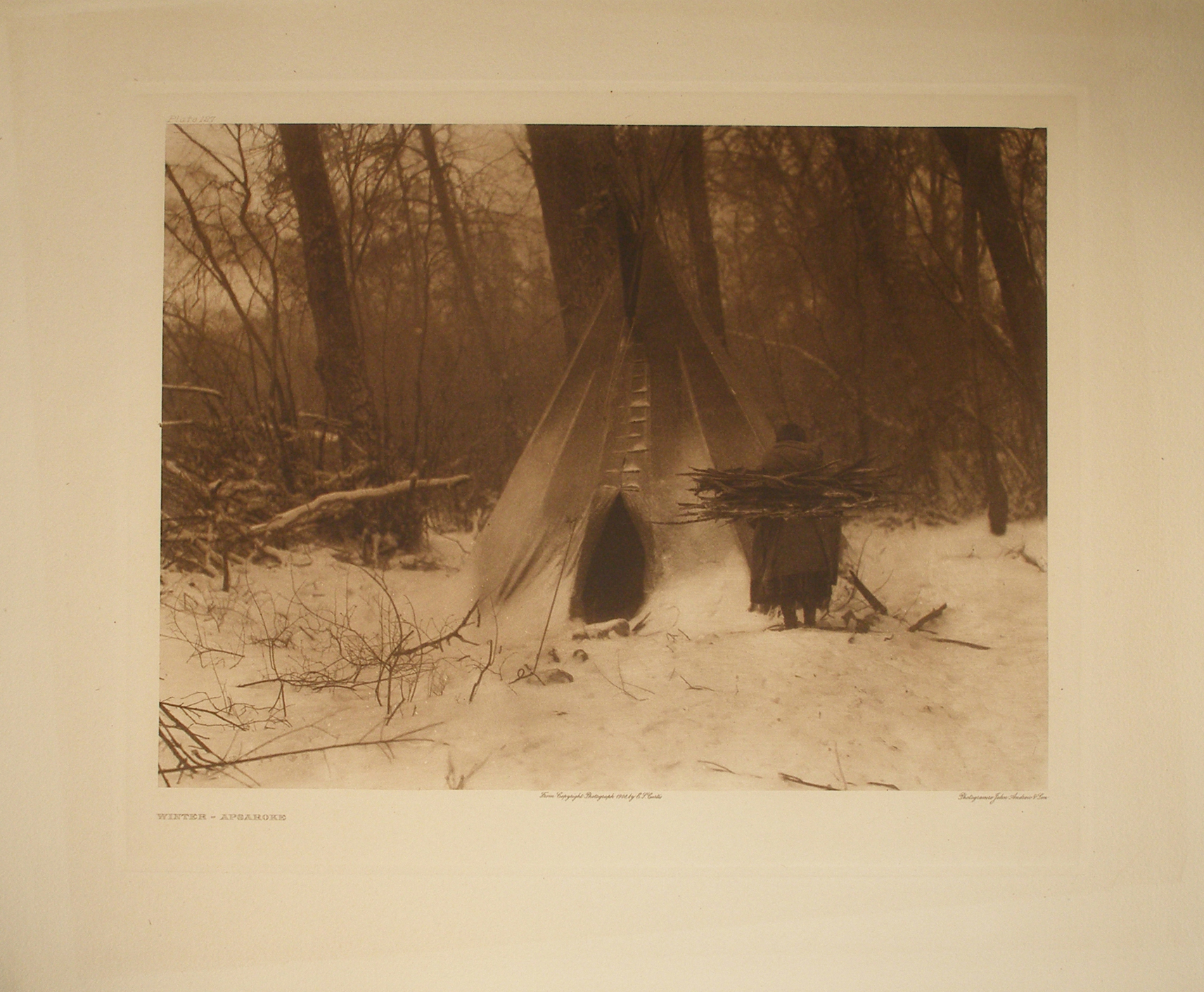

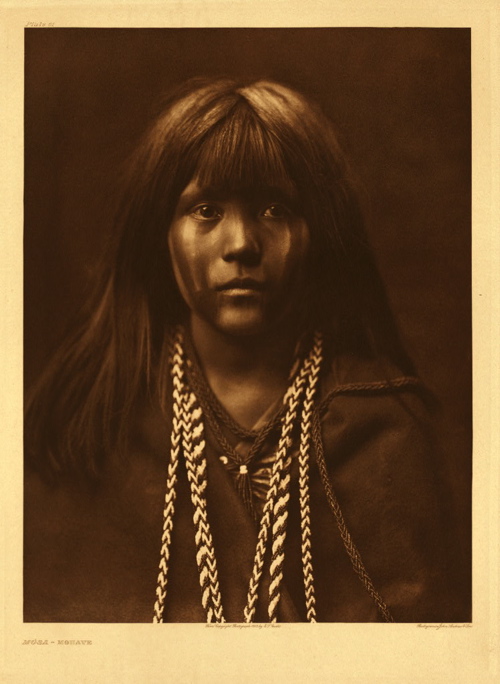

Edward S. Curtis. “Mosa – Mojave” 1903. This is the extraordinary portrait by Curtis that so enchanted millionaire J.P. Morgan that he became a crucial patron of The photographer’s Curtis’ pioneering anthropological effort to document the death of Native American culture and life in its original forms.

Edward S. Curtis. “Mosa – Mojave” 1903. This is the extraordinary portrait by Curtis that so enchanted millionaire J.P. Morgan that he became a crucial patron of The photographer’s Curtis’ pioneering anthropological effort to document the death of Native American culture and life in its original forms.  Rembrandt van Rijn “Self Portrait,” oil on canvas 1661, This late-life masterpiece was on display last year at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Rembrandt van Rijn “Self Portrait,” oil on canvas 1661, This late-life masterpiece was on display last year at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Rita Cox with one of her “underground railroad” quilts, from the book “Hidden in Plain View.” Photo by Richard Allen.

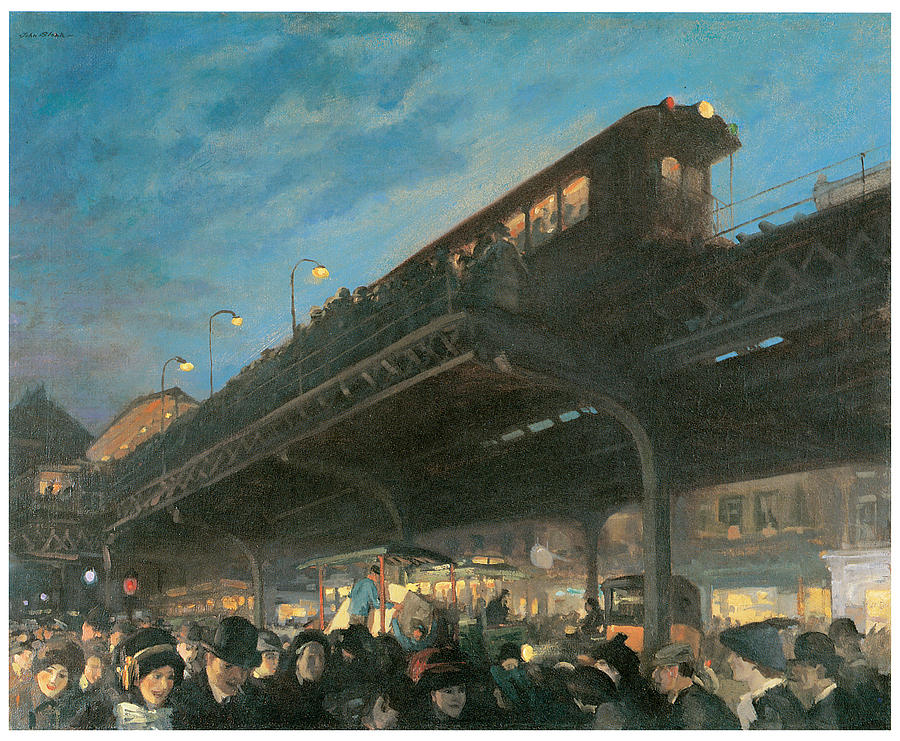

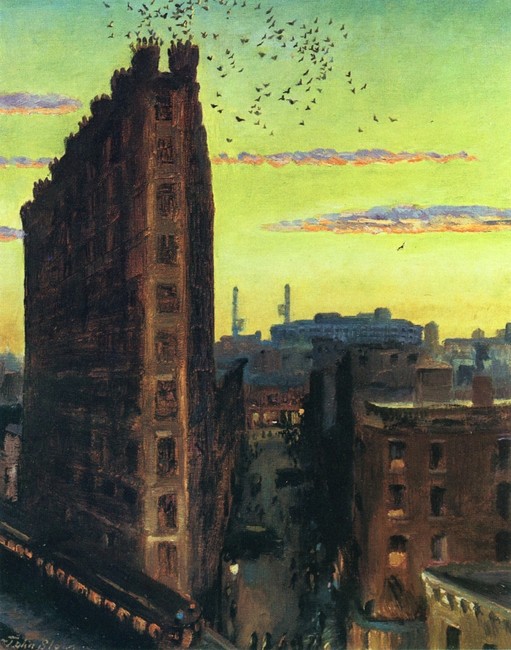

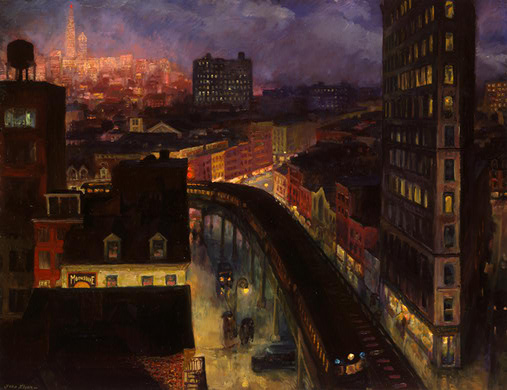

Rita Cox with one of her “underground railroad” quilts, from the book “Hidden in Plain View.” Photo by Richard Allen. John Sloan “View of the City from Greenwich Village,” oil on canvas 1922

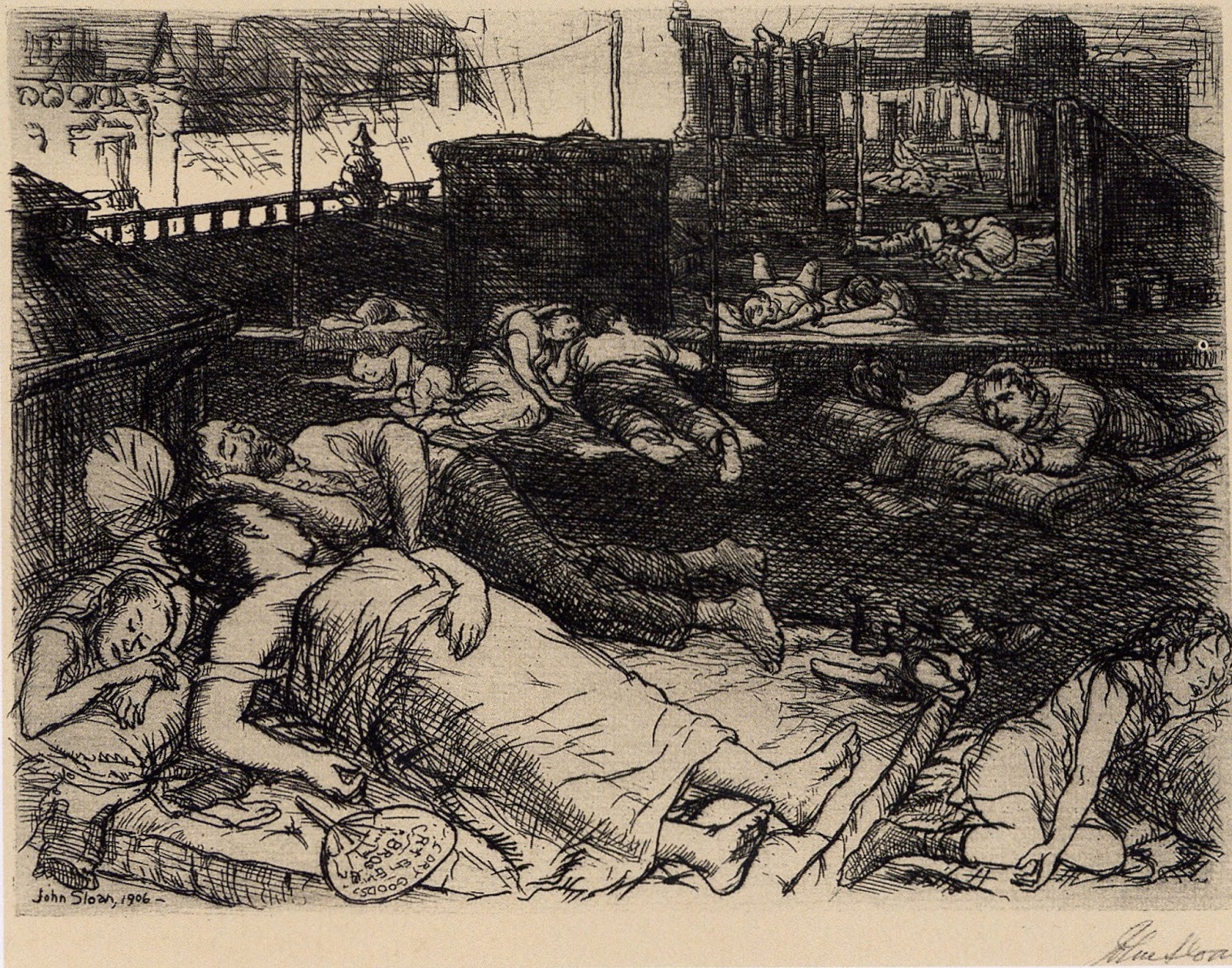

John Sloan “View of the City from Greenwich Village,” oil on canvas 1922 John Sloan. “Roofs, Summer Night” etching 1906

John Sloan. “Roofs, Summer Night” etching 1906

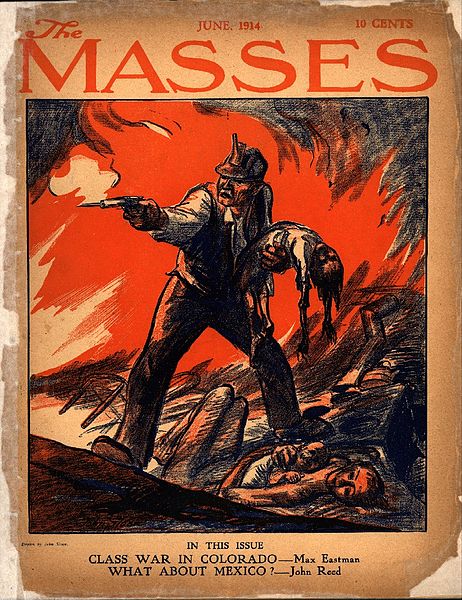

Sloan was a political artist as well as an acute social observer. Here’s a provocative cover illustration for the left-leaning periodical “The Masses.” It depicts a scene from the notorious Ludlow massacre. The tragedy involved

Sloan was a political artist as well as an acute social observer. Here’s a provocative cover illustration for the left-leaning periodical “The Masses.” It depicts a scene from the notorious Ludlow massacre. The tragedy involved