Afternoon light floods into the Milwaukee County Historical Museum’s west side, for the current interactive exhibit tracing 200 years of Milwaukee music history. All photos by Kevin Lynch, unless otherwise noted.

Light enters the Milwaukee County Historical Society from both the building’s oblong sides and intersects in the atrium with a bow effect of illumination, one side stronger, depending on morning or afternoon. This is due to the building’s narrow shape, almost recalling a flatiron building, and it’s location, standing free from other buildings, on the southeast corner of State Street at 910 N. Old World 3rd St.

Across the street is the closest structure, the low-lying Milwaukee Journal- Sentinel building. On the museum’s east side is Pere Marquette Park, and beyond the Milwaukee River and the courtyard behind the cream-white marble facade of the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts, which reflects even another subtle layer of light depth.

The natural light washes into the two-story open atrium encompassing a display area and even the museum offices, enclosed by a clear glass wall. And yet regal chandeliers add another luminous dimension. There’s no other public building atmosphere quite like it, that I can think of. My photos below, all taken without a flash, suggest the warm aura of enlightenment, and the transporting quality that can fuel any visitor’s historical awareness and imagination.

The Milwaukee County Historical Society, from the southeast facade. Courtesy www.milwaukeehistory.net

The purpose for our visit was the current exhibit, Memories and Melodies: 200 Years of Milwaukee Music. running through April 29. Hours are 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mondays through Saturdays, and admission is $7, and free for members, and children under 12 years.

It isn’t just pure history, as real and aspiring musicians get chances dream or to recollect, or experiment by trying out – through headphones only – some electric drums, electric bass and a close knock-off of a Gibson Les Paul guitar, which I plucked a bit and heard the classic tonal purity and incision that has driven so many great guitarists to use it, since the mid-1960s. Less furtively, you can also test out a few ukuleles and a violin (for all to hear) and a few other acoustic instruments. In a side room stands on old upright player piano which will play its rippling roll, visible in a small window, if you pump the foot pedals with a touch of deftness.

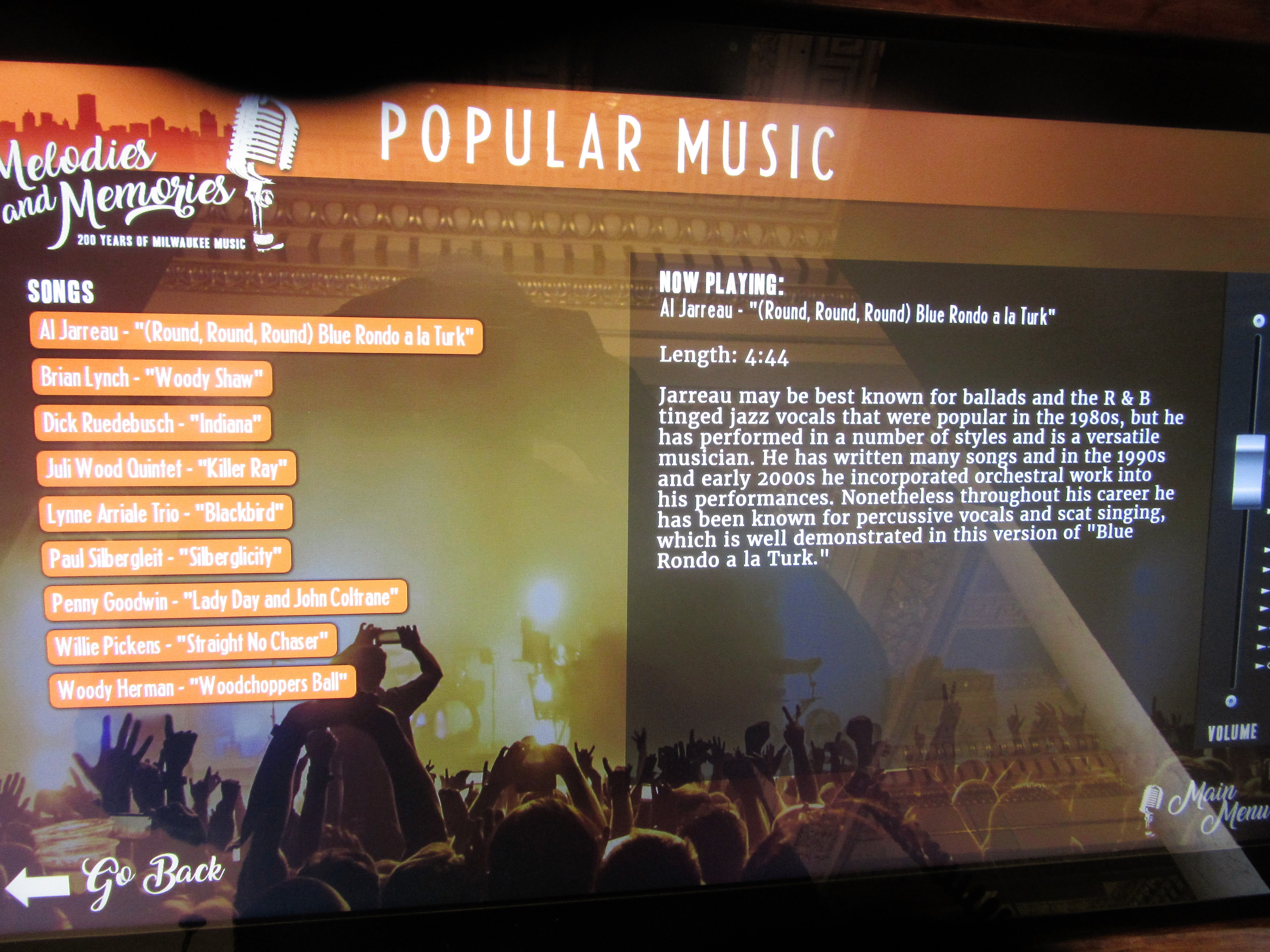

The interactive displays include several head-phone listening booths in which you can choose touch screens from several different large categories of music, such as classical concert music, jazz, and a lively array of vernacular musics. The individual selection choices are superb examples of recorded music by famous Milwaukee musicians, singers, composers, arrangers, orchestras and bands.

The displays range from Native American music to Florentine Opera founder John-David Anello, Tin Pan Alley songwriter Charles K. Harris and the Milwaukee Police Band, the oldest in the nation. Also find here iconic and revered electric guitar inventor Les Paul, Country Music Hall of Famer Pee Wee King, The Talking Heads’ Jerry Harrison, the folk-punk rock trio The Violent Femmes and the Latin roots-rock band The Spanic Boys, among others.

I listened to music by the recently-passed singer Al Jarreau (as noted in a recent Culture Currents post on Al:

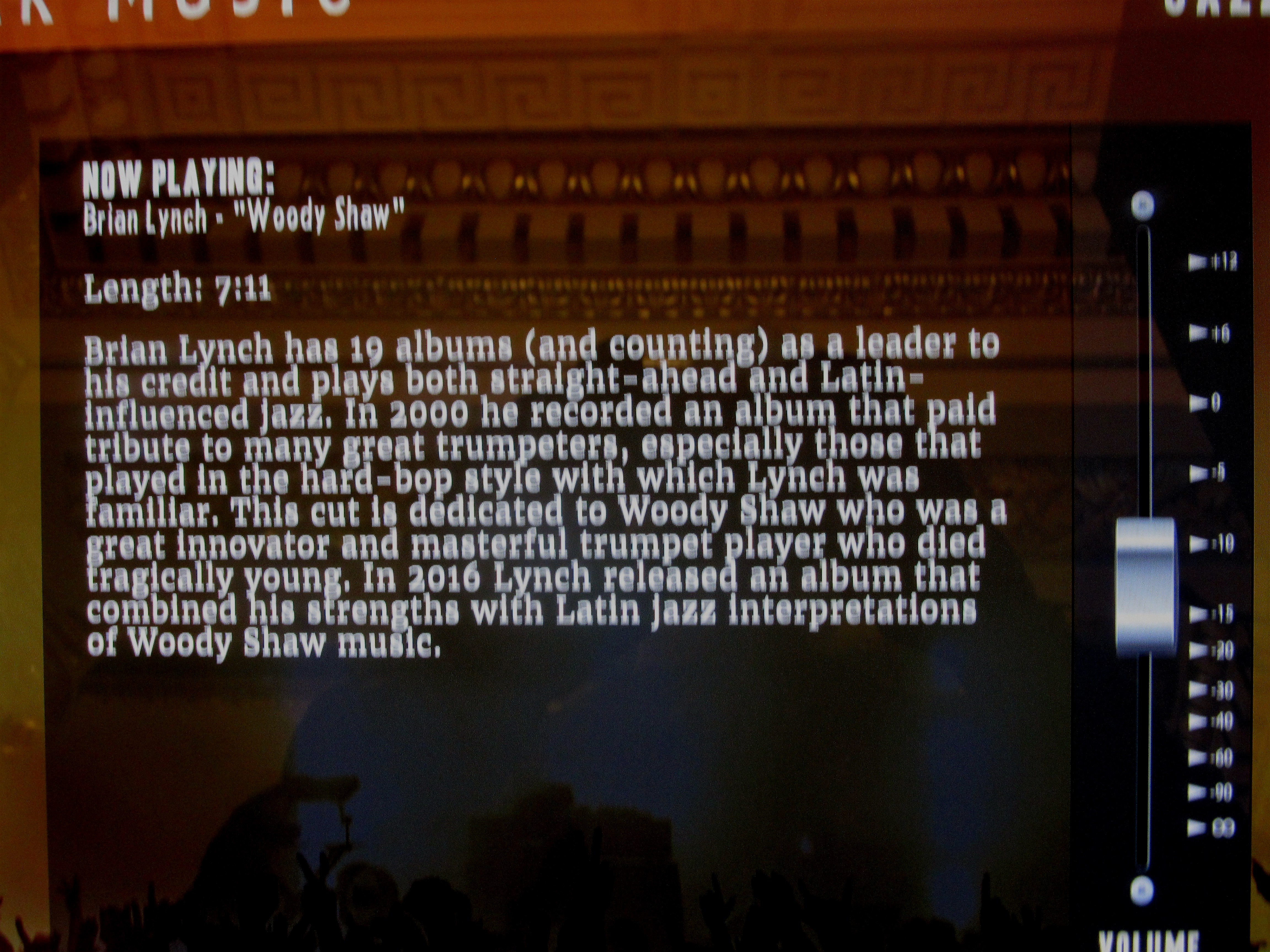

). I also heard Grammy -winning jazz trumpeter Brian Lynch (no relation to this writer), playing his affectionately heady tune titled “Woody Shaw,” for the trumpet giant who influenced Lynch and many others. I enjoyed a lovely piece by the celebrated and prolific contemporary composer Daron Hagen, “Cradle Song (Intimamente),” the second movement from his Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra. The Milwaukee native gained fame for “Shining Brow,” his luminously-moving Madison Opera-commissioned opera about Frank Lloyd Wright, but has composed and excelled in virtually all forms of the classical music tradition.

In this show, you learn that Sesame Street’s lovably self-glorifying chanteuse Miss Piggy was based on Wisconsinite Hildegarde — in her vibrato-twirling vocals, curl-crazy hairstyle, long gloves and glittery garb, right down to her compulsive flirtatiousness. She was born as Hildegarde Loretta Sell in Adell, WI, and raised in New Holstein, but the colorful cabaret diva trained at Marquette University’s school of music.

Hildegarde (upper), courtesy dwfmu.org, and Miss Piggy (above), courtesy muppetsonline.com

In a way, Hildegarde, though straight, was the female role model for another Milwaukee musical legend, Liberace, the profusely flamboyant pianist who was a pioneer of gay performers.

Given that it’s Black History Month it’s good that African American-dominated genres of jazz, R&B and blues stand strongly represented in the informative displays of Milwaukee beacons. Besides the multiple Grammy-winning Jarreau, who effortlessly traversed jazz, R&B and pop, there’s soul stylist Eric Benet as well as The Seven Sounds, led by irrepressible singer Harvey Scales, and a display panel on the highly original jazz saxophonist Bunky Green.

In the blues category, you’ll find tribute to Short Stuff, the band that defined urban blues style here for decades. I recall, as a concert opener they once unforgettably stole the show from the famous San Francisco band Big Brother and the Holding Company, although this was after Janis Joplin had left the group. Short Stuff featured black singer and keyboardist Junior Brantley, along with firebrand harmonica player Jim Liban.

Also feted here in the blues category, The Stone-Cohen Blues Band lives on today in a different form as Leroy Airmaster, featuring the two nominal leaders of the original band, harmonica virtuoso Steve Cohen and guitarist Bill Stone.

The exhibit honors Milwaukee jazz/R&B singer Al Jarreau, pictured at left, and local jazz greats including guitairist Manty Ellis and sax and flute player Berkeley Fudge, pictured here in a band with pianist Eddie Baker, bassist Harold (Hal) Miller, and drummer Sam Belton.

African American stalwarts of the Milwaukee jazz scene represented here include the still-active and vital guitarist Manty Ellis, who’s a walking history of Milwaukee jazz himself, and saxophonist-flutist Berkeley Fudge, a dominant figure here for decades, an example of unassuming creative class.

Exhibit curator Ben Barbera admits the exhibit is hardly comprehensive. It’s about artists who came from here. This exhibit does go “beyond genre and performer to explore music’s role in Milwaukee’s economic, technological, entertainment, and social spheres.” But it doesn’t really cover historical events or performances, per se.

Off the top of my head, I would include as historically important many countless moments at Summerfest: headliners Sly and the Family Stone, The Band, Stevie Wonder, Paul McCartney, the Rolling Stones, and on side stages, Bill Monroe, Dizzy Gillespie, Los Lobos and Lucinda Williams among many others. Great local concert and club venues would need their due, though the show includes posters for the clubs Teddy’s, Cafe Voltaire and the Starship.

Then there was the Midwest Rock Fest at State Fair Park in the summer of 1969, which pre-dated Woodstock by several months, and a line-up nearly comparable, including the short-lived super-group Blind Faith and Led Zeppelin, in its ballsy and bluesy early days. Virtually all the guitarists (Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, etc) were playing the Gibson Les Paul guitar, like it was a new sort of competition for who could wrench the most power and soul out of the new guitar. I was there for the Midwest Rock Fest all three days and life wasn’t the same after that.

The Kool Jazz Festival in Washington Park in 1982 boasted a blinding jazz firmament, including the vocal triumvirate of Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, and Carmen McRae, along with Ornette Coleman, Mel Torme, Gerry Mulligan, Dizzy Gillespie, George Shearing, Spyro Gyra, Chico Freeman, The Modern Jazz Quartet, and The Great Quartet with Freddie Hubbard, McCoy Tyner, Ron Carter, and Elvin Jones.

Built in 1935, the historical facility’s relatively modest physical size limits the show’s scope. But bigger ain’t always better. You won’t get museum fatigue here, and perhaps we should be grateful that no one has tried to build a clumsy addition to this superb self-contained work of architecture, in the French Renaissance Beaux Arts style, which might look like a giant tumor more than anything else.

(More photos below)

____________