“His story being ended with his pipe’s last dying puff, Queequeg embraced me, pressed his forehead against mine, and blowing out the lights, we rolled over from one another, this way and that, and very soon were sleeping.” – End of Chapter 10, “A Bosom Friend,” from Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville*

Call Me Ishmael: A Hallucination on Moby-Dick, Off-the-Wall Theatre, Milwaukee, closing Sunday, March 29, www.offthewall.com

Two Trains Running, Milwaukee Repertory Theater, Milwaukee, running through May 12 www.MilwaukeeRep.com

These two plays seem to dwell in far different worlds: one across the immense, perilous wilds of the world’s great oceans in the mid-1800s, and the other in a time-worn diner in a black neighborhood of Pittsburgh in 1969.

It’s reasonable to doubt that the great African-American playwright August Wilson was thinking about Moby-Dick in this play, situated smack dab in the middle of his grand Pittsburgh Cycle, a series of 10 plays each set in the 10 decades of the 20th century, to demarcate and explore the African-American experience.

Call me Idiot. Go ahead. But hear me out. For starters, the ambition of Wilson’s play cycle surely rivals Melville’s mighty saga of “mariners, renegades and castaways.”

A week ago Friday night, I saw Off the Wall Theatre’s eccentrically capacious production of company director/playwright Dale Gutzman’s Call Me Ishmael , which he subtitles “a hallucination on Moby-Dick,” but very clearly and specifically adapted from Melville’s text.

Less than 48-hours later, I saw The Milwaukee Rep’s sterling production of Wilson’s Two Trains Running. Given my creative and scholarly involvement in Melville, and strong interest in Wilson, I’m hardly shocked that the two plays have commingled in my mind over the last week. The swift affinity between ostensibly foreign identities is perhaps akin to the extraordinary brotherhood that develops between Melville’s novice sailor/narrator Ishmael and the great harpoonist man of color, Queequeg. He’s described in Gutzman’s program notes as “the Prince of Kokovoko” (as Melville identifies him, from a fictional island in the South Pacific. “It is not down in any map; true places never are,” as Ishmael, the expansively philosophical young explorer, famously asserts.).

Part of Melville’s ever-echoing greatness, running through The Great American Novel and his oeuvre, are the character archetypes he forged, starting with the colorful crew members of the whale ship Pequod, a sort of floating, rag-tag democracy. Yet a tyrannical, obsessive captain dominates that diverse aggregation, which surely foretells America’s current political situation.

However, both plays, as presented here, gravitate, through thick hurly-burly, to the power of love, as a magnetic and redeeming force in human affairs.

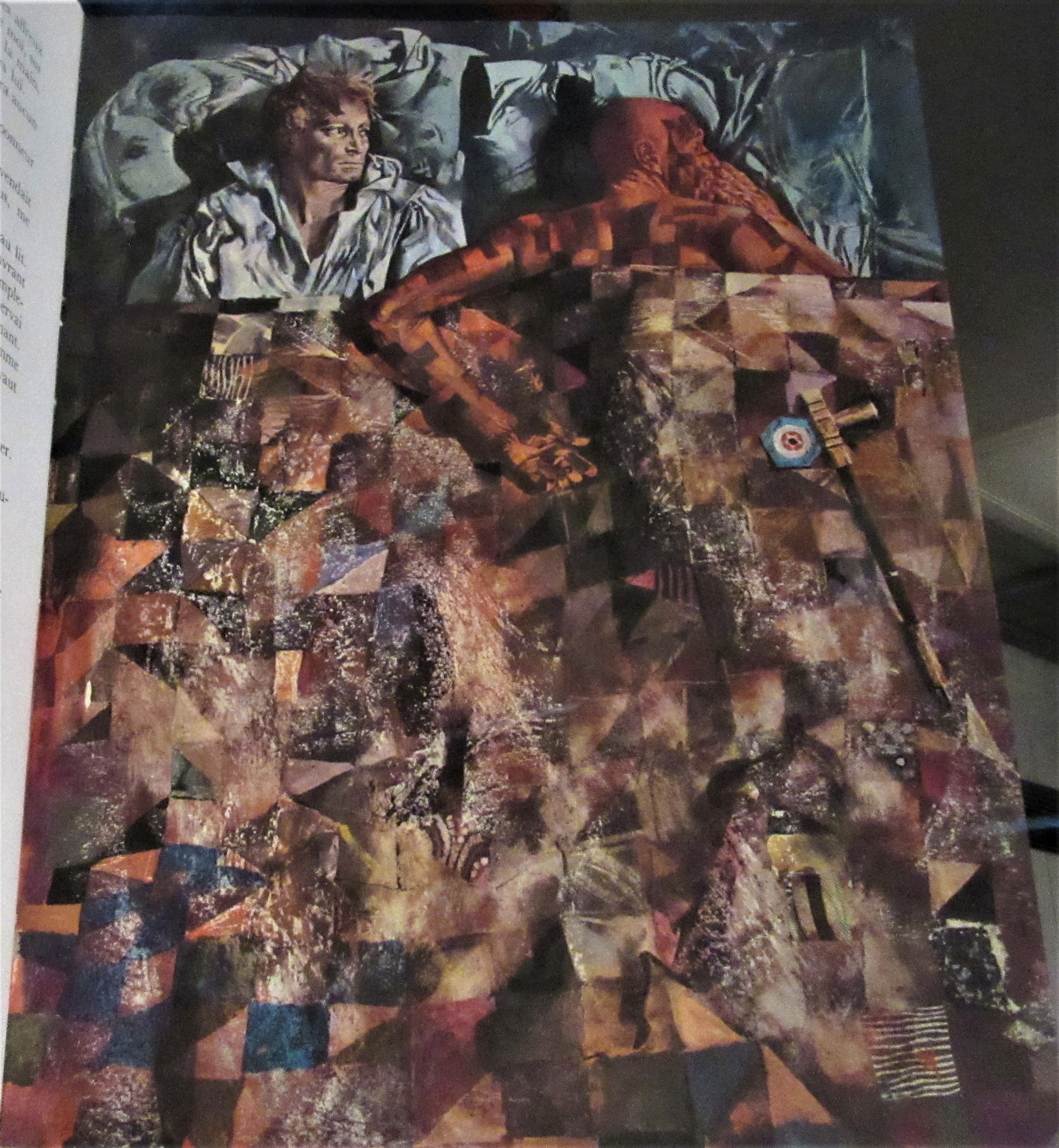

Queequeg is more central to Ishmael‘s radically compressed social and dramatic dynamic than in Melville’s almost impossibly vast literary canvas. I recently encountered a striking symbol of that in the beautiful painting (pictured at top) at the recent Melville exhibit at Chicago’s Newberry Library, celebrating the author’s 2019 Bicenntenial. And, of course, this primitive but oddly regal “other” is displaced by thousands of miles from his Polynesian home, not unlike the players in Wilson’s story, displaced from the South by The Great Migration north, a key subtext of his Pittsburgh Cycle. And, like virtually all of the black male characters in Wilson’s play, Queequeg endures a kind of double-consciousness (a la DuBois), living in New England’s New Bedford while ashore, with his conspicuously-tattooed Polynesian body.

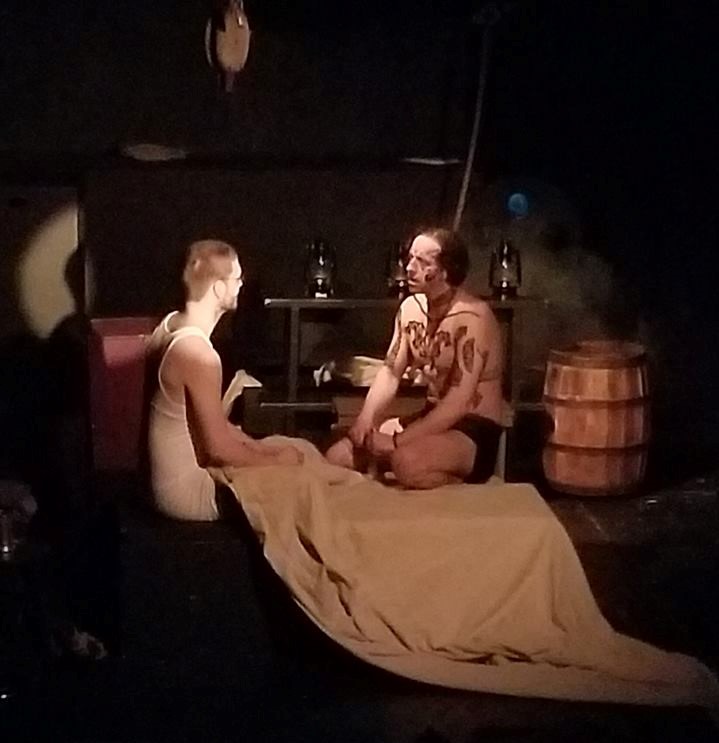

Here Ishmael (Jake Russell, foreground) and tattooed harpooner Queequeg (Nathan Danzer appear joined at the hip, but in this moment the crew of the Pequod is transfixed by the astonishing destructive power of the whale Moby Dick, in Off-the-Wall Theatre’s “Call Me Ishmael.” Courtesy Off-the-Wall.

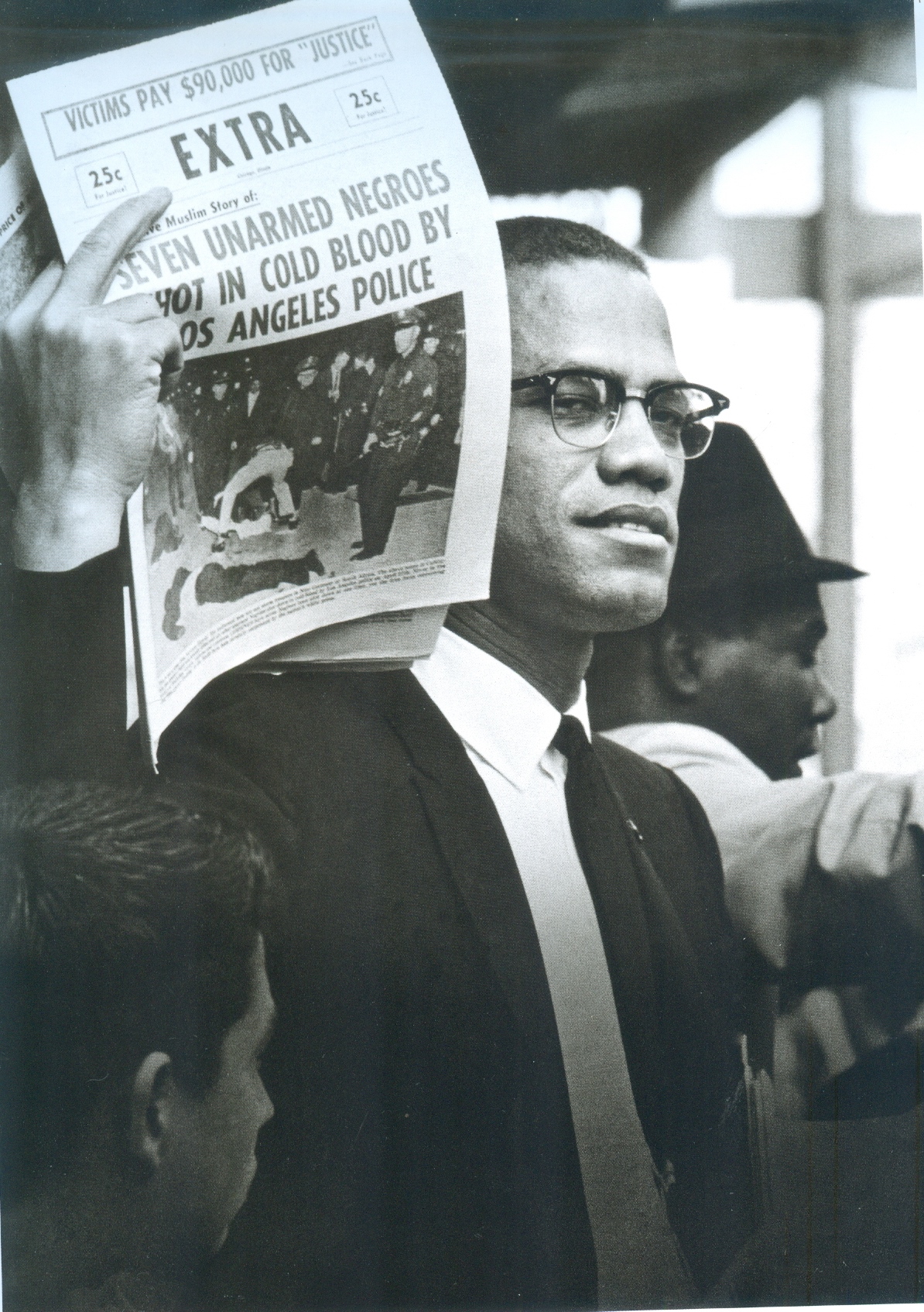

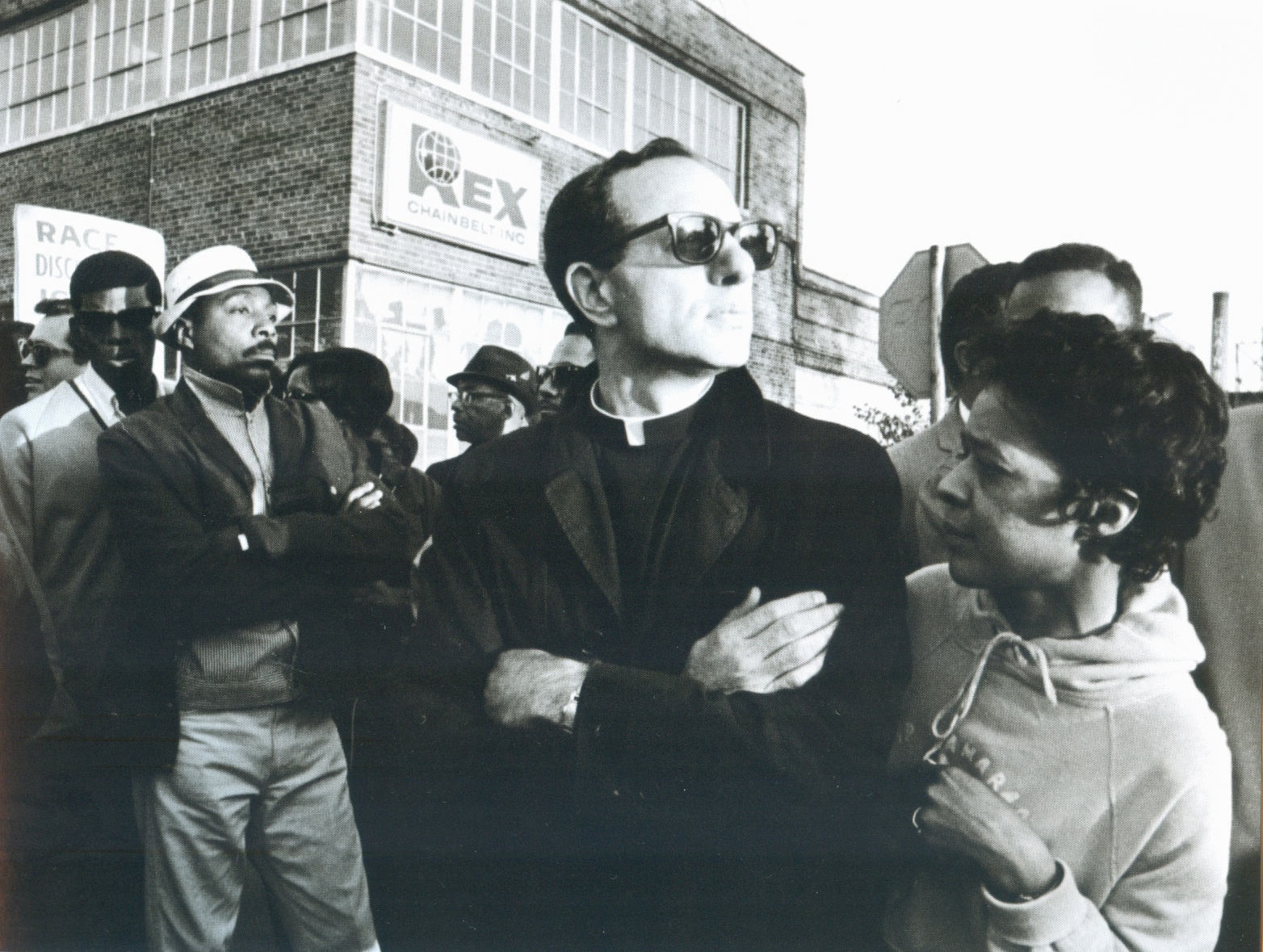

In the late 1960s, playwright Wilson strongly called for for a “separatist black aesthetic” at a time when asserting black identity felt crucial. Indeed, the key political event of Two Trains is an impending Hill district neighborhood rally for famous black radical leader Malcolm X. And enough anger runs through Wilson’s whole play cycle, as much as I’ve seen of it, but just as much anguish at the injustices of American society that befall African-Americans.

Diner owner Memphis (Raymond Anthony Thomas, center) rails over being forced to sell his property to the city for far less than he thinks is it’s worth, in the Milwaukee Rep’s production of “Two Trains Running.” Play photos courtesy milwaukeerep.com

In a 2006 essay Philip Beidler convincingly traces Wilson’s defiance of the proverbial black man’s burden, through Ralph Ellison, to Melville’s remarkable novella Benito Cereno, based on a true story, about a Trojan Horse of a slave ship, being run by mutinous slaves while deviously maintaining appearances to delude white power conventions and perceptions.

Another Melville novel Two Trains seems to reference is The Confidence-Man or, His Maquerade, as two of the play’s characters are con men, similarly working over a small group of people. One is aptly named Wolf, a lottery numbers runner (bet money-trafficker) who seems to bilk the idealistic romantic Sterling, himself a recently-freed petty thief, out of half of his lottery winnings by blaming it on the boss man.

But the real vulture is neighborhood undertaker, named West, masquerading in professional three-piece suit and top hat. He constantly hovers in the diner asking for coffee sugar from waitress Risa, but never using it. He’s trying to set up diner owner Memphis, who hopes to sell the restaurant to the city’s eminent domain project for $25,000 (ten grand more than the city offers), and to move back to his rural settlement in Tennessee. West, who’s rich from many a literal death of dreams, offers Memphis $20,000 for the place, and says he’ll invest the other $5,000 well enough to double his return and complete the payment.

Memphis flirts ardently with the offer – just the sort of thing one of the shysters in Melville’s con-man parade might float. The Confidence-Man brilliantly satirized American Gilded-Age hustle and greed. Wilson posits that black folk have learned to hustle, but more often to merely survive or strive for modest dreams.

The heart of the play is Sterling, the heart-of-gold ne’er-do-well who improbably tries to woo Risa, in step after bumbling step.

A beauty, she’s sadly had so many men hustle her that she has mutilated both of her legs so as to deface her allure. The playwright knows well how to deal out a complexity of human emotions and allow elements of pathos to arise. This centers to varying degrees on the two wouldn’t-be lovers, on Memphis, and especially in the character of mentally challenged Hambone, who repeatedly marches into the diner demanding “I want my ham!” He may have lost his mind waiting for twenty years for a local butcher who’ll only offer him a chicken, when he feels a big ham is his due.

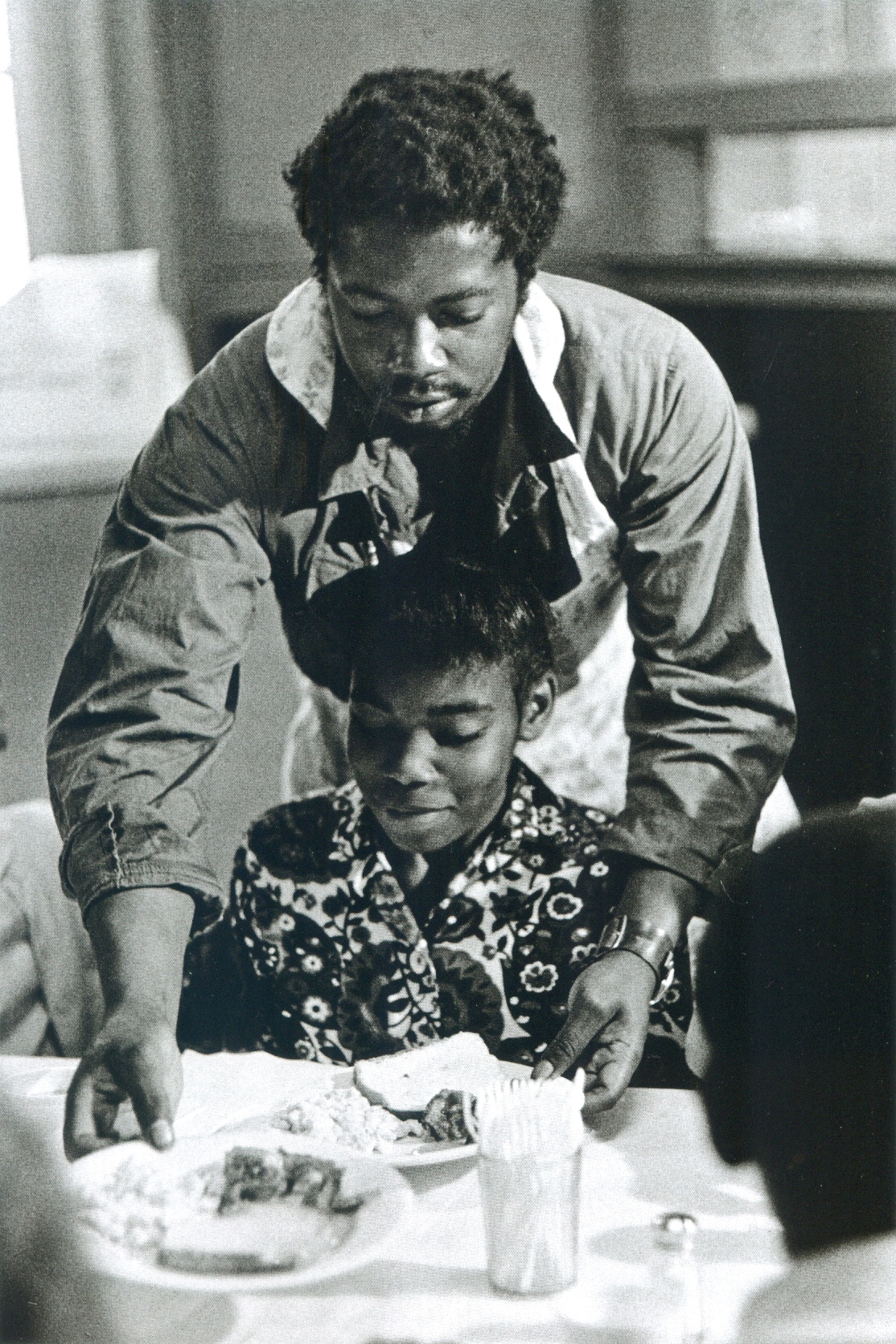

Mentally challenged Hambone (Frank Britton, right foreground) repeatedly demands that he receive the ham that a local butcher has refused to give him for two decades, in “Two Trains Running.”

But strength and fortitude always sustain the souls of these black folk. rising to the surface past all rage or anguish. And ultimately Two Trains is a romance as is Moby Dick – interpersonally, though Melville’s is daringly unconventional, between men – but both also in sense of genre, as tales striving through reality for something larger, bigger, and more beautiful (see, too, the whale embedded in the stunning quilt in the painting at top).

Off the Wall’s Ishmael bravely ventures perhaps where no other black-box theater has, in staging Melville’s monstrously promenading sperm whale of a story. Playwright Gutzman blends Melville’s vivid and eloquent prose with nifty plot compressions, and the evocative effects of the great adventure arise with winning ingenuity, daring, imagination, and comedy, as Melville did to the max, in 135 comparatively short chapters. And by strongly playing up the book’s homoerotic undercurrent of Ishmael and Queequeg’s relationship, Gutzman has pushed the story directly into today’s liberated acceptance of same-sex love.

The homoerotic aspects of the close relationship between Ishmael (Jake Russell, left) and Queequeg (Nathan Danzer) were emphasized in Off the Wall Theater’s adaption of “Call Me Ishmael,” an adaptation of “Moby-Dick.” Courtesy Off the Wall

Psychologically-burdened waitress Risa (Malkia Stampley) is a pivotal character among all the males in “Two Trains Running.”

In Two Trains, Sterling is a sort of voluble and naïve Ishmael and, with her scarred legs, Risa is a kind of Queequeg, an exotic “other” for being the only woman in the cast. She possesses latent powers and allure yet, unlike the Polynesian, her potential for love is fraught and baggaged. Risa may be a sort of tortured angel. Is she judged by the content of her character? Are her flesh wounds also akin to Christ’s? This was a natural analog – as is her name, Risa – given that we saw the play on Easter Sunday. Do her body marks tell a story, as Queequeg claims his do? Perhaps the embodiment of the state of “original sin.” Is that too Christian? Melville, the skeptic of man-made “Christianity,” might think so. Yet a dying neighborhood prophet named Samuel also haunts this play. Could the woman’s marks signify a universal suffering, that of humanity?

And the seemingly witless Hambone reveals a deeper presence, recalling Moby-Dick‘s Pip, the black cabin boy who compulsively rattles his tambourine – and falls overboard unnoticed and nearly drowns. The trauma destroys his sanity but he emerges “touched” by God. Even bedeviled Capt. Ahab then senses this possible spiritual lifeline and takes Pip under his wing, while continuing his diabolical quest to kill the White Whale.

These and other mystical strains in Moby-Dick have resonated down through cultural history and Wilson’s play has an off-stage character, recurrent in his work, Aunt Esther, a spiritual figure who is a “washer of souls” and reportedly 322 years old, which aligns her birth with the arrival of the first African slaves to America. She seems to provide the keys to the dreams of these slave descendants. Aunt Esther always asks them to pay her by throwing $20 in the river. So the monetary symbol of meager and grandiose dreams becomes an offering to the watery forces of nature and a float-on-a-wave faith, a most Melvillian of themes.

Further, Wilson’s title derives from a Muddy Waters blues, “Two Trains Running.” But “there’s not one going my way.” The singer bemoans his star-crossed destiny in humble watery terms. “I wish I was a catfish swimming in the deep blue sea/ I’d have all you pretty women fishing after me.” Poor Sterling, who desperately wants Risa as his bride, also brings to mind another cast-your-fate-to-the-water blues classic, Robert Johnson’s “Walkin’ Blues”: “People tell me worrying blues ain’t bad/ But it’s the worst old feeling I ever had. Fish run to the ocean, ocean run to the sea. if I don’t find my baby, who child gonna marry me?” 2

_____________

- That exact Melville quote, without any attribution – except an enigmatic “B” – is the last liner-note acknowledgement of “thanks” in the noted American singer-songwriter Jeffrey Foucault’s 2001 debut album Miles from the Lightning.

- 1 Philip Beidler, “King August,” Michigan Quarterly Review, Fall, 2006 http://https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?cc=mqr;c=mqr;c=mqrarchive;idno=act2080.0045.401;g=mqrg;rgn=main;view=text;xc=1http://

- 2 Pittsburgh’s Hill district hosted many jazz and blues musicians traveling from New York to Chicago through much of the early 1900s, when Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle begins. Both songs were originally “race records,” marketed only to black audiences, but this lyric version of “Two Trains Running,” and the “Walking Blues” lyric, are both on the 1966 album East-West by The Butterfield Blues Band, one of the first-ever integrated electric blues bands. Bob Dylan also later performed “Two Trains” not infrequently.