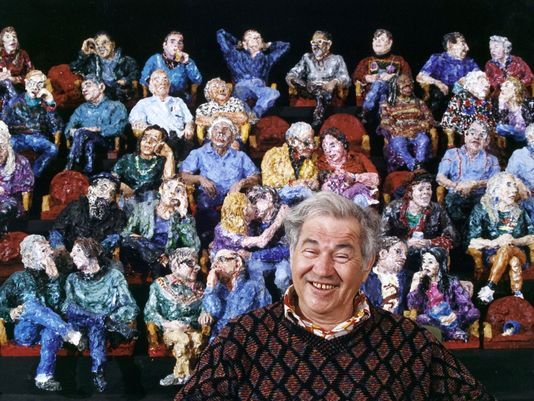

The late Adolph Rosenblatt, with his many quirky friends in his large sculpture “My Balcony.” Courtesy UWM Photo Services

Adolph Rosenblatt Retrospective: Moments & Markers, Jewish Museum of Milwaukee, 1360 North Prospect Ave., closing Sunday, August 27. Hours are Monday-Thursday 10-5 PM, Friday 10-3 PM, Sunday 12 noon-4 PM. Free parking is behind the museum building.

I first met Adolph Rosenblatt in the early 1970s when he taught me life drawing in a class at UW-Milwaukee. He helped inspire me to switch my major focus to sculpture, from advertising design. He had just begun exploring the possibilities of figurative clay sculpture, after being primarily a painter. And when I took a basic sculpture class I was seduced by the sensual and palpable life I sensed in wet, malleable clay in my hands.

In our life-drawing class Rosenblatt would set up a large wooden board with mounds of wet clay on a drawing easel and bring the goopy lumps to life. This incongruously proved quite relevant to our ostensibly two-dimensional discipline, as we were trying to create the illusion of sculptural three-dimensionality on paper, with graphite or charcoal.

He and art professor Joseph Friebert helped liberate my drawing technique, which had been hard-edge and perhaps cold in its attempt at realism. Rosenblatt, a short, slightly hunched man, who died in February of natural causes at 83, would wander among our drawing easels, making incisive, wry and sometimes slightly outre suggestions. After all these decades I don’t recall any, so I’ll borrow from students quoted in a display at the wonderful Rosenblatt retrospective Moments & Markers, at the Jewish Museum of Milwaukee, 1360 North Prospect Ave., which is closing this week on Sunday, August 27.

One student took seriously Rosenblatt’s seemingly counterintuitive advice: “If a painting isn’t working, paint out your favorite part.” I think Rosenblatt understood the tendency of artists to fall in love with their own work, to even fetishize a part they’ve focused on and perhaps overworked. When all else failed, he would say “F–k the world and just paint.” Either was a way to let loose and let go, and see your work with fresh eyes.

And did this man ever have fresh eyes! However, one thing he did miss, it appears, was a self-portrait. Seeing again at his marvelously rough-hewn, vibrantly animated work, I see it reflecting the face of Rosenblatt himself. He should have done a sculptural self-portrait, because his face was a slightly incongruous assemblage of mutating forms. He could concentrate deeply but he always seemed on the verge of slipping over the edge into utter hilarity, of dissembling into laughter, and his infectious giggle of glee. His whole face would become a smile of many mirthful, slightly askew parts, almost Picasso-esque. But I suspect his disheveled lack of self-regard kept him from a self-portrait’s potential narcissism. He had a great eye with a fine mind, a master observer of others.

And the humor that coursed through his whole body transmuted into his art, which might be called “The Human Comedy.” And, not unlike Honore de Balzac’s novel masterpiece La comedie humaine, this artist saw and interpreted the world with a deep sense of the fallibility, absurdity and neuroses amid the beauty in each person. Rosenblatt also gives his figures a gritty gravitas that rarely feels solemn. The retrospective does reveal his social and political consciousness with a series of life-sized head portraits sculpted of former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon.

Another is of Anita Hill, famous for her sexual harassment testimony against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. “I had to tell the truth,” Rosenblatt quotes her in the fired clay. “It is a high-tech lynching.” Hill here is expressive and beautiful, all of her facial contours rise as if struggling up a hill. If only her case had arisen today, as male sex abusers in power face their day of moral and legal reckoning. Rosenblatt’s sculptural memorial to Hill demarcates her as a pioneer of today’s “#Me Too” movement.

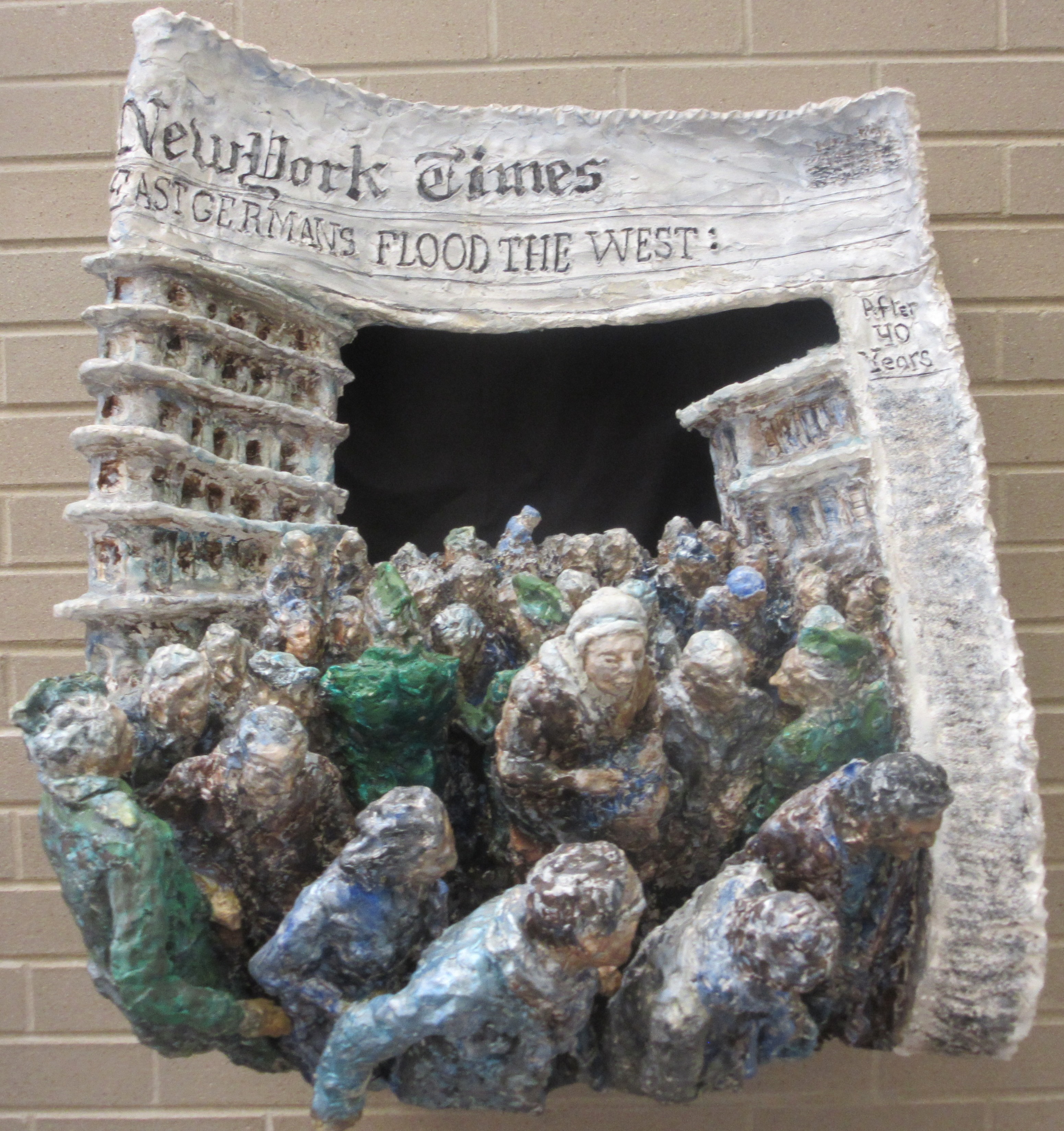

Another example of the peculiar dynamism Rosenblatt could convey in a high-relief sculpture is “New York Times – Berlin Wall” in which he re-creates a front page of The New York Times in clay, with the headline “East Germans Flood the West: After 40 Years.” The front-page “photograph” is a mass of humanity surging forward toward the viewer, brimming with pent-up hunger for deliverance and freedom, palpable in the heaving urgency of their bodies pouring out of the sculpture.

Rosenblatt’s “New York Times – Berlin Wall.”

In such work you sense, beneath the surface, how humanity’s crookedly ambling collectivity often flirts with, or converges into, tragedy. As with the Anita Hall sculpture, in our era of vast swaths of desperate war refugees and immigrants, “Berlin Wall” carries powerful political and dramatic urgency, which literally reaches out to touch the viewer. Rosenblatt carried on a grand tradition of high-relief sculpture that goes back to the Greeks.

And yet, he will likely be most remembered for his depictions of modest, undramatic scenarios. He would take his boards full of clay into places like the Oriental Pharmacy lunch counter and render customers, or to the balcony of the Oriental Theater, which both became fairly “epic” works, if such a word could be applied to such striving to capture unassuming human humility and comedy.

One of these centerpieces of the show is the massive tableau, “My Balcony” (1997) depicting the Oriental Theater’s balcony with 50 or 60 people sculpted in quirky detail. You see couples necking, hands and legs entwined, a mother with a squalling child on her knee, another mom nursing her infant in the theater’s ostensible darkness. Each figure seems to radiate a virtual lifetime in the subtle facets of Rosenblatt’s gestural, fingerprinted way of modeling the figure, as if each has been shaped by the slings and arrows of fortune, the vicissitudes of time. This mastery of revelation gives his work a timeless and fascinating humanity – as if each figure has many tales seeping from their pores.

Adolph Rosenblatt vividly captured a wide swath humanity in his large sculptural tableau, “My Balcony.”

The second major piece is less of a frontal display than the balcony, more of an experience of a quotidian place of unique yet oddly familiar people. “Oriental Pharmacy Lunch Counter” (1987) was a now-gone Milwaukee institution of sorts, a layout of long dining counters that snaked its way along five or six lanes of countertops. It was often jam-packed, as it is here and one feels more voyeuristic than with “My Balcony,” because you walk can around it and peer at the mood and situation of each customer and lunch-counter employee, eating, or chatting or daydreaming. One wonders what brought each one of them to the counter on this particular day.

One corner of Rosenblatt’s large tableaux, “Oriental Pharmacy Lunch Counter.”

The work’s total effect is an exposure of human types that Balzac might have described had he lived in Milwaukee in the 1980s. These two big pieces have a discursive quality akin to Balzac’s sprawling masterpiece, though ambitious on their own terms. Other influences I detect are one he likely admitted to, Honore Daumier, the great artistic lampooner of middle and upper 19th century French classes. Daumier also did highly textural sculpture, not far different in style from Rosenblatt’s. Despite his barbed satire of the powerful and pretentious, Daumier betrayed tender affection for the hoi polloi, as in his classic “Third-Class Carriage.” His superb painting of industrialized France depicts the quiet fortitude of passengers in the third-class train carriage including, like Rosenblatt’s Oriental balcony tableau, a nursing mother.

Honore Daumier’s “Third-Class Carriage.” Courtesy metmuseum.com

I also sense at least a parallel sensibility in now-famous “underground” cartoonist Robert Crumb’s artlessly skilled renderings of slightly gawky and sometimes sadly comic humans. I see, too, the Crumb parallel in Rosenblatt’s whimsical way with architecture, as in the delightful 1977 sculpture “Houses on Bartlett.” Here, a snowy landscape seems to pulse through its steep, rippling surface and even the houses almost expand and contract, as literally breathing from the lungs of Gaia. Or, more prosaically, an animated cartoon stands smack in the middle of a gallery.

The show’s second gallery shows different sides of the artist, including a good-hearted satire of elderly sun worshipers in “Snow Birds,” and a surprisingly ominous, noirish cast-bronze scene in which human features are wiped away.

Rosenblatt’s “Snow Birds.”

A revelation lies in one of Rosenblatt’s large paintings. The stunning untitled oil bears the influence of another great Jewish artist, Marc Chagall, who is represented in the first gallery by a mural-size wall hanging. Chagall’s famous magically flying humans appear in Rosenblatt’s canvas, floating amid a burning atmosphere of abstract impressionism/expression. Such color-soaked brilliance brings us back to his fired clay sculptures, most of which are deftly and creatively hand-painted, adding another dimension to his 3-D art.

Rosenblatt’s large, untitled abstract impressionist painting, with floating figures reminiscent of Marc Chagall.

And to that end, for all this show’s riches, I must close by returning to the movie theater balcony, a very revealing detail. On the furthest occupied seat to the right in one balcony row sits a man isolated by empty chairs around him, the only notable cavity in the crowded balcony scene. His head turns away from the whole crowd; his left leg rests on his right knee in a posture of a man whiling away the afternoon at the movies, hidden from the world. But he’s not watching the movie, only staring into his own private infinity.

This lonely figure tells a deeply human story in Rosenblatt’s “My Balcony.”

His slightly shambling presence, to me, seems the essence of a quietly bereft but almost stubborn solitude. Rosenblatt has purposely captured him in this manner as a flip side – among the most common and universal sides – of The Human Comedy, the heart of loneliness. And for that, it’s a testament to Adolph Rosenblatt’s insight into humanity, his expressive skill and unerring generosity of spirit.

May Adolph live on, at a lunch counter in the skies, with bottomless cups of heavenly, hearty coffee and camaraderie.

All photos by Kevin Lynch, unless otherwise noted.