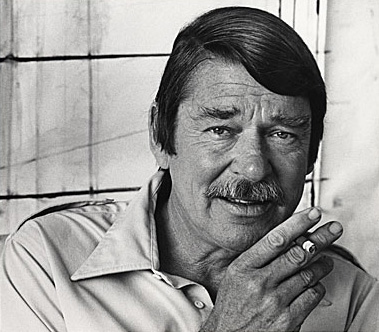

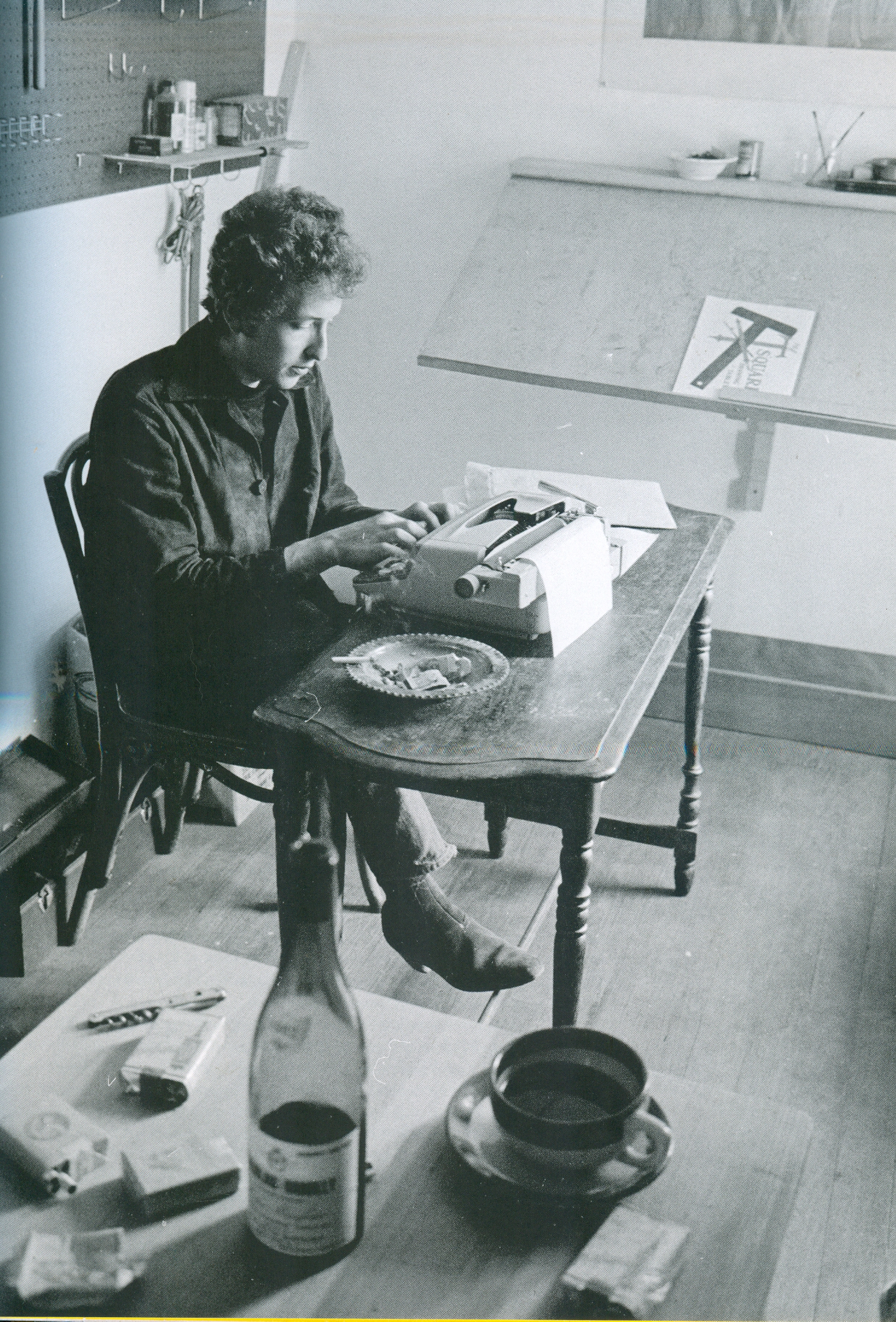

Bob Dylan writing in Woodstock, N.Y. during the period when he composed the songs for his earliest albums of originals. From the new book “Dylan:Disc by Disc” from Voyageur Press. Photo credit: Douglas Gilbert/Redferns/Getty Images

November has come, dour as a rusty pail, and I mourn my favorite month. October was a calendar painting delaying my spirit’s decay — when the leaves and thistle burnish and glimmer, and fill the air with the pungency of natural death cycles. So I’ll surely face the howling wind, as I’ve done Novembers past.

Yet old songs stir. I’ve realized that Bob Dylan did November’s song as well as anyone ever has. The times are a-changin’ to a wintry world and Dylan understood and expressed this in new found terms of old traditions. On the first page of Moby-Dick, Melville’s Ishmael had invoked “the damp, drizzly November of my soul,” when he found himself “involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet.”

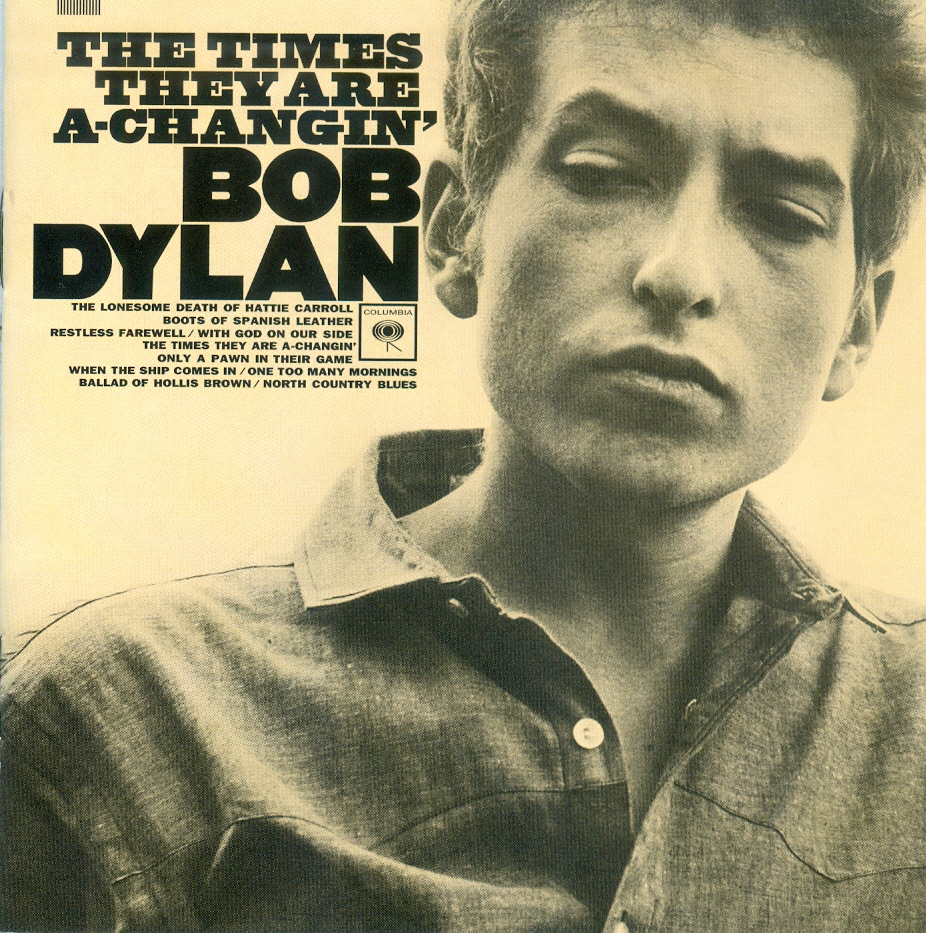

Dylan invoked similar spirits in his early masterpiece, The Times They are a-Changin’ from 1964, even though he was merely 22 years old when he wrote and recorded these songs.

As often as we may have considered, loved or even forgotten it, the album is worth revisiting at least once again, to hunker in November’s chill.

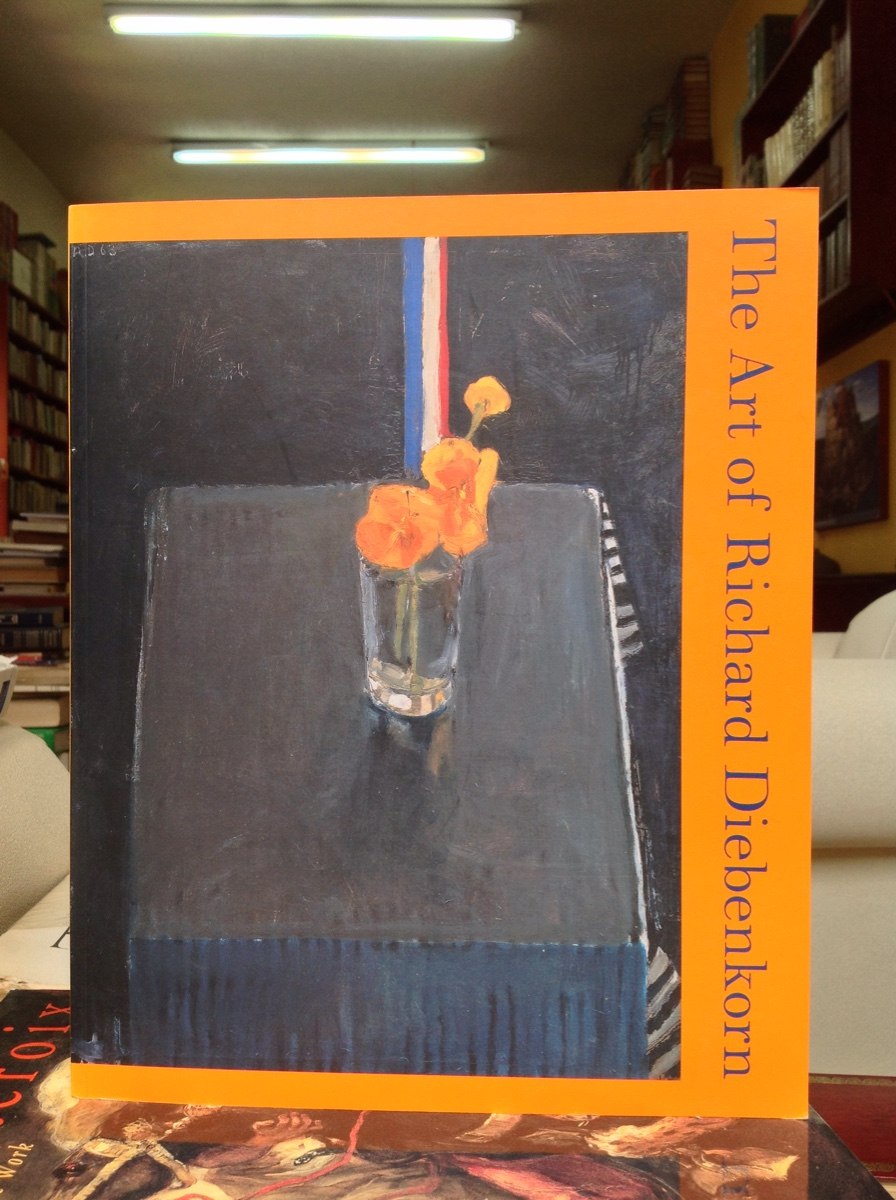

This essay is also prompted by an elegantly crafted new coffee table-sized book Dylan: Disc by Disc, edited by Jon Bream and introduced by Ritchie Unterberger, with conversational and insightful comments on Dylan’s 36 studio recordings from Rodney Crowell, Robert Christgau, Tony Glover, Joe Henry, Jason Isbell, Rick Ocasek, Suzanne Vega, NoDepression.com editor Kim Reuhl and others.

Of course, we know that Dylan understood what he had accomplished with this album. He knew how, in 1964 it spoke to the war-mongering paranoia of presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, and a November election that resoundingly rejected that, with Dylan’s help. He spoke for the restless ferment rising from a new generation, and for black Americans finally calling for just rights with another poet/leader named King.

So it’s commonly understood as Dylan’s greatest protest album, and perhaps the greatest such album of all time. But it’s protest is not purely political or social rhetoric. It’s greatness lies in the cries for the lives of very specific people, whether very real or archetypes he dreamed up. Dylan’s complex compassion bleeds from his pores.

Yet he seemed to sense he could not top the album on its terms, so followed it with more private expression and poetic imagery in the ensuing Another Side of Bob Dylan. Nevertheless, he said he would always stand behind his earlier work, and I’m sure nothing gave him greater pride than The Times.

And yes, for me there’s irony in that I have stated previously and made it a mission to explore the increasing multitude of excellent singer-songwriters inspired by him, who followed and remain shortchanged because of his towering position. Still, this is an expanding literature of our roots musics, a new sort of American Renaissance.

Texas singer-songwriter Steve Earle once brashly declared “I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say Townes van Zandt is the greatest songwriter in the world.” 1

Yet, Dylan, while he breathes, remains the man. I swear you can talk of Dylan as if Shakespeare’s in the room and learn anew. The bard of his times dramatizes the truth in echoing lives and circumstances, be they Elizabethan or mid-60s America. For one thing, many white people still fear a rainbowed nation, as in 1964 or like the racism dwelling in say, The Merchant of Venice or Othello.

Although The Times brims with poetic fire, Dylan chose here to speak as plainly as he could. In many ways, this was his noblest effort, rich with incident, detail, drama, romance and ardor. He seems as committed as ever. Each song deserves an encomium, but I will pick and choose somewhat, and try to offer fresh insights. I shy away from the opening title song, as iconic as it is, as his echoing fanfare of truth and challenge, partly because it also speaks in the broad abstract, even with his brilliant particulars.

A liner photo from the 2005 CD re-issue of “The Times They are a-Changin’.”

I prefer to linger over the powerful story-songs and other pronouncements simmering with finely-hammered irony, and the two exquisite romances.

So “Ballad of Hollis Brown,” that sorriest of South Dakota settlers, follows with shuddering emotional power, driven beneath by the insistent drive of Dylan’s guitar drone, like church bells tolling in hell.

Your baby’s eyes look crazy/they’re a tuggin’ at your sleeve/you walk the floor and wonder why/every breath you breathe.

Doesn’t every despairing man ask why me? as a heart-lacerating refrain, even if there are logical reasons? What happened to bring it to this? I always worked things out, until now.

Your babies are crying louder now/It’s pounding on your brain/your wife’s screams are stabbing you/like the dirty drivin’ rain.

And then the horror creeps slowly upon his despair: Way out in the wilderness/a cold coyote calls/your eyes fixed on the shotgun/that’s hangin’ on the wall.

I’ll quote only the ending because hearing Dylan perform the climax is the only the way to do it justice. And yet astonishingly, for such tragedy, Dylan renders a last ray of hope with no false sentiment, not for this man in his befouled world. Nay, hope for every man who may be born that dark day, and learn and plow his field to plenty from the shroud of that November, even if he may not avoid such a fate himself.

Dylan’s evocative mastery is as sternly cinematic as a black-and-white John Ford film. Indeed Ford could’ve wrought something with long craggy shadows from Dylan’s tale of Hollis Brown. Because we need remember, this is America as much as the ever-celebrated hope and will and caring.

Album cover photo by Barry Weinstein.

From this stark story, Dylan upshifts grinding gears to the epic American mythology of “With God on Our Side.” This is the second telling of his first great masterpiece of anti-war irony, “Masters of War” from the preceding album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, which in many ways remains my favorite Dylan album, but only as a personal preference. And he brilliantly makes this broad-shouldered declamation with the most unassuming of introductions: Oh, my name is nothin’/ my age it means less/The country I come from/is called the Midwest.

His voice begins to recite our country’s darkest and most mythologized chapters with a slow, chest-heaving sorrow. Our history books tell it/ They tell it so well/The cavalries charged/The Indians fell/The cavalries charged/the Indians died/Oh the country was young/with God on its side.

Yes, we have Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and other magnificent testaments. But has anyone ever told the Native American story with such succinct rightness?

Dylan takes us through the Spanish-American war and both world wars and faces the Cold War in which he wrote the song: But now we got weapons of chemical dust./If fire them we’re forced to/ then fire them we must./One push of the button/and a shot the world wide./And you never ask questions/when God’s on your side.

He tells us that he spent a long time thinking about these matters before the song came and, despite his simmering anger, he does not speak as a moral arbiter. He humbly allows us our freedom.

He invokes Judas Iscariot’s betrayal of Christ and concludes: so now as I’m leavin’/I’m weary as hell/The confusion I’m feelin’/Ain’t no tongue can tell/The words fill my head/and fall to the floor/if God’s on our side/ He’ll stop the next war.

Dylan is heroically honest yet bereft of a solution. Like so many before him, he invokes God in his darkest hour. I figure Dylan knew that God would not stop the next war, and this song remains the summation of the dire irony he laid before us, the countless grotesque ways that God’s name has been taken in vain. And Dylan seems to understand that the free will we exercise weighs on God’s heart much as anything. I suspect he might concur with Norman Mailer’s late-life cosmology which posited that God is not omniscient; rather that He is a flawed creative artist. So He may be unable to stop humanity’s fratricidal and ecological madness, until perhaps the Second Coming or whatever the final hour brings.

Dylan wisely follows this mighty jeremiad with pure grace, the album’s most hushed and intimate reflection, “One Too Many Mornings.” We hear what a superbly romantic singer he can be, the perfect counterpoint to his bracingly ironic voice.

The song takes a poetic measure of time akin to the following year’s “My Back Pages”: As the night comes in a fallin’/the dogs’ll lose their bark./And the silent night will shatter/from the sounds inside my mind/For I’m one too many mornings/and a thousand miles behind.

It’s a story of a young man reflecting from where he sits, having lain with his lover. That sun-filtered scene, and perhaps everything leading up to it, compels him to realize life can catch up to you, ambush you at any moment, even that one when you finally begin to truly savor it.

“North Country Blues” is a more muted death dirge than “Hollis Brown,” and a magnificent evocation of the coal miner’s life. It tells a true, harsh story that leads to the devaluing of the coal product and of the lives of those who labor for it.

So the mining gates locked/and the red iron rotted/and the room smelled heavy from drinking.

Where the sad, silence song/made the hour twice as long/as I waited for the sun to go sinking.

“Only a Pawn in their Game” tells the tale of Medgar Evers, one of the first martyrs of the civil rights movement. A handle hid out in the dark/ a hand set the spark/ two eyes took the aim/ behind the man’s brain/ but he can’t be blamed/ he’s only a pawn in their game.

Of course, it is a tale as contemporary as tomorrow. Because, for all the progress that Frederick Douglass believed in, and that we have accomplished, we struggle mightily with race, and the nation’s Original Sin. Dylan understands it is the contradictions of our system that betray us all, even the manipulators. Dylan sings with the weary regret of a witness who has seen it too many times before. That was 1964. How many of us are witnesses today of the same doleful sort? And what are we to do about it? Those were Dylan’s implicit questions, back then.

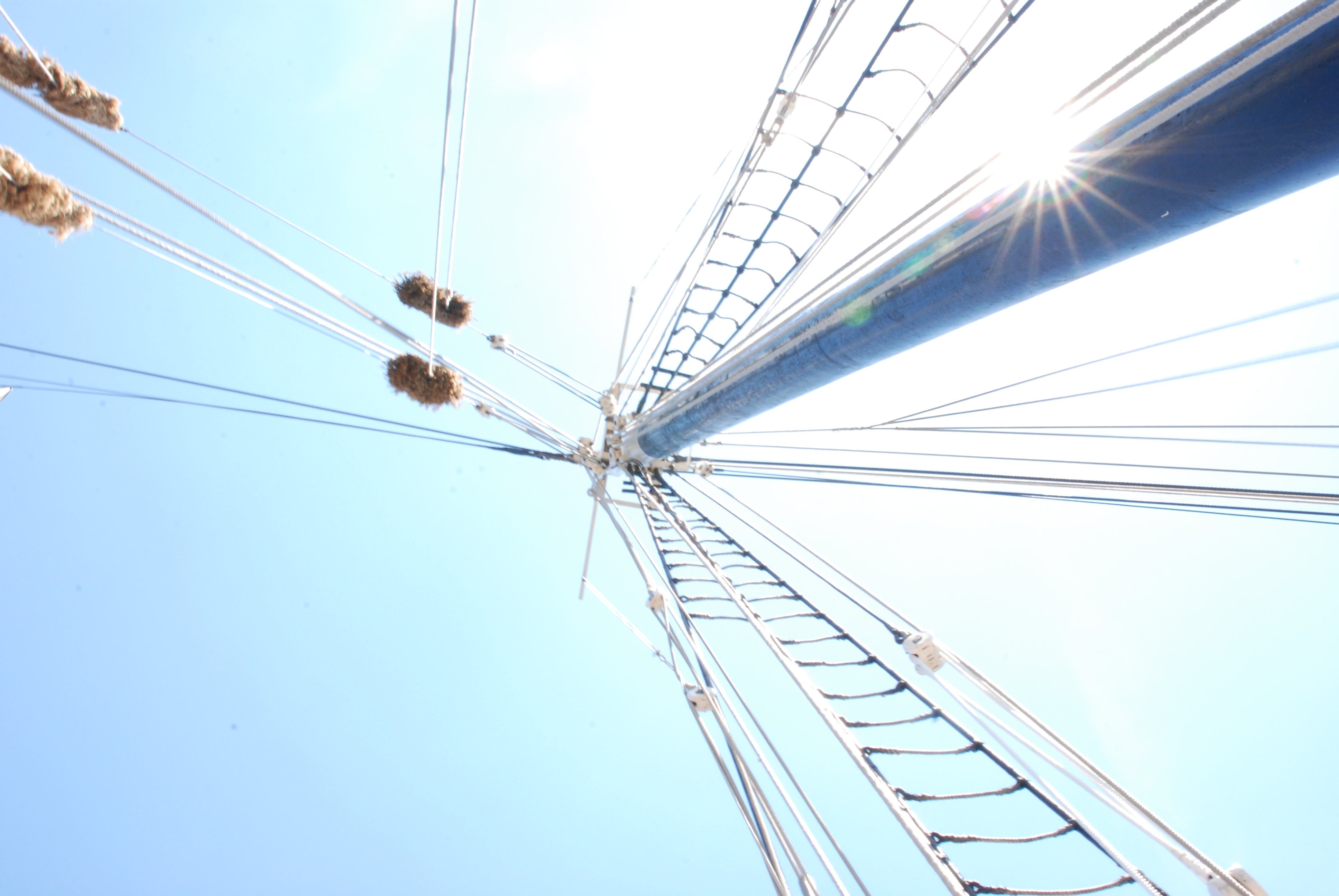

Again he wisely gives us respite, with perhaps his loveliest November evocation of romance in all its splintering splendor. “Boots of Spanish Leather” is like the ocean waves it uses as a metaphorical and literal setting for the distance between two lovers in a romance that may or may not have experienced one too many mornings. Dylan imagines the two lovers corresponding over the sea with letters. 2

One lover longs for the other’s lips. And yet, I got a letter on a lonesome day/it was from her ship a sailing/saying I don’t know when I’ll be coming back again/it depends on how I’m feelin’.

The seemingly forsaken lover musters gallant graciousness: So take heed, take heed of the Western wind/take heed of the stormy weather. And yes, there’s something you can send back to me/ Spanish boots of Spanish leather.

The lover repeats the word “Spanish” as a way of savoring the beautiful artifacts that might symbolize their love, and its leave-taking. It’s as if he cannot let go in that moment, and yet he does. Perhaps the vast ocean waves that have gently jostled beneath this tender story loosed the moorings of the love they once trusted as firmly entwined.

Oh, but if I had the stars from the darkest night/ and the diamonds from the deepest ocean/ I’d forsake them all for your sweet kiss/ for that’s all I’m wishing to be ownin’.

“The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” tells another true story of American racial shame, one far less known, but no less potent, than Medgar Evers’. William Zanzinger killed Hattie Carroll, a maid. The wealthy young tobacco farmer reacted to his deed with a shrug of his shoulders/and swear words and sneering, and his tongue it was snarling/ In a matter of minutes on bail was out walking.

The killer gets a six-month sentence. Oh, but you who philosophize disgrace and criticize all fears/Bury the rag deep in your face/for now’s the time for your tears.

Perhaps no song Dylan ever wrote more effectively juxtaposes wrenching pathos with boot-heel disregard, and the curious and wide range of reaction to the events that is peculiarly American.

Finally “Restless Farewell” is perhaps Dylan realizing he needs to end his great testimony to the changing times. Changes few could have predicted or forewarned except someone like him. He became our Paul Revere, our Raven quoting doom, our secular minister who preached with a harmonica hooked to his a neck, a wily voice and words to anguish, wonder and march to.

And in 1964, he was our bard of November and its howling reprisal of summer’s lost innocence. Most remarkably, he was a kid from Hibbing, Minnesota, as extraordinarily gifted as he was obsessed with America’s vernacular musics, brash and brawling, impassioned and commingling.

Oh, every thought that’s strung a knot in my mind/

I might go insane if it couldn’t be sprung.

But it’s not to stand naked under unknowin’ eyes.

It’s for myself and my friends my stories are sung…

So I’ll make my stand/and remain as I am

And bid farewell and not give a damn.

___________

All lyrics, in italics, by Bob Dylan, copyright 1964

1 Today Earle competes for that title, as does Lucinda Williams or Roseanne Cash or Springsteen, among others. Or perhaps James McMurtry exemplifies the lessons that Dylan passed down on this album of monumental storytelling. His superb 2015 album Complicated Game demonstrates how he’s learned from Dylan as well as his father, the great Texan novelist Larry McMurtry, and made all that his own. So, if you want to go somewhere after The Times, where Dylan himself chose not to, go to James McMurtry who can sing story-songs with comparable compassion, anger and eloquence.

2 One of my very favorite interpreters of Dylan, Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin-based singer-songwriter Bill Camplin, brilliantly underscored the emotional contrast of man and woman in his interpretation of the “Spanish Boots” narrative on his album Dylan Project One. Camplin clearly uses both gender voices, rendering the female with conviction, thanks to singing which effortlessly shifts from high baritone to falsetto.

A “widow’s walk” built atop a roof in the harbor at Mystic, Conn., where wives of whalers would watch the sea in hopes of seeing their husbands returning.

A “widow’s walk” built atop a roof in the harbor at Mystic, Conn., where wives of whalers would watch the sea in hopes of seeing their husbands returning.

A spectral reflection of the whaling ship in the water below its mooring place.

A spectral reflection of the whaling ship in the water below its mooring place.

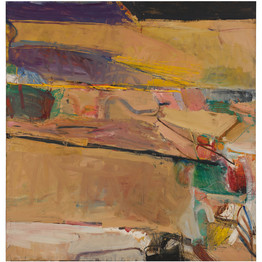

Richard Deibenkorn “Berkeley # 54.” This image doesn’t do justice to the scale of this painting (61 by 59 inches) currently on display at the Milwaukee Art Museum, through September 20. Courtesy albright-knox.com

Richard Deibenkorn “Berkeley # 54.” This image doesn’t do justice to the scale of this painting (61 by 59 inches) currently on display at the Milwaukee Art Museum, through September 20. Courtesy albright-knox.com