“The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” oil on canvas, Arshile Gorky, 1944

“The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” oil on canvas, Arshile Gorky, 1944

Van Gogh to Pollock: Modern Rebels – Masterworks from the Albright-Knox Gallery, through September 20. Milwaukee Art Museum

If actor James Dean ever picked up a paintbrush, the result might’ve looked something like a Jackson Pollock, but without the artistic skill for orchestrating controlled abandon. What amounts to an art rebellion? If you can go back to a key moment, a kind of rebellion sometimes occurs when an artist makes an extraordinary, radical move.

Imagine watching Pollock when he “broke the ice” as his contemporary Willem DeKooning said. Pollock broke most of the rules of painting, pacing panther-like around huge canvases stretched out on the floor. His paint dripped, swirled and splattered — and blew the concept of depiction to smithereens.

“Modernism is about rebels who look at convention, and say, ‘I’m gonna stand that on its head,’” says Milwaukee Art Museum chief curator Brady Roberts.

That’s a key aspect of the excitement and resonance of “Van Gogh to Pollock: Modern Rebels.” The exhibit of major works from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo.

Pollock’s engulfing “Convergence” from 1952 will show how differently art could express and, even more radically, do. The so-called “action painting” will also be represented by DeKooning’s tension-filled “Gotham News” from 1955, among others. They’re two prime “rebel” examples from Albright-Knox which has “the best collection of abstract expressionism in the world,” says Roberts.

“Convergence,” oil on canvas, Jackson Pollock, 1952

The mid-20th century movement that made New York the “art world capital” will be offered in its “the historical context” — “post-impressionism, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Picasso, surrealism, Joan Miro and more,” Roberts says.

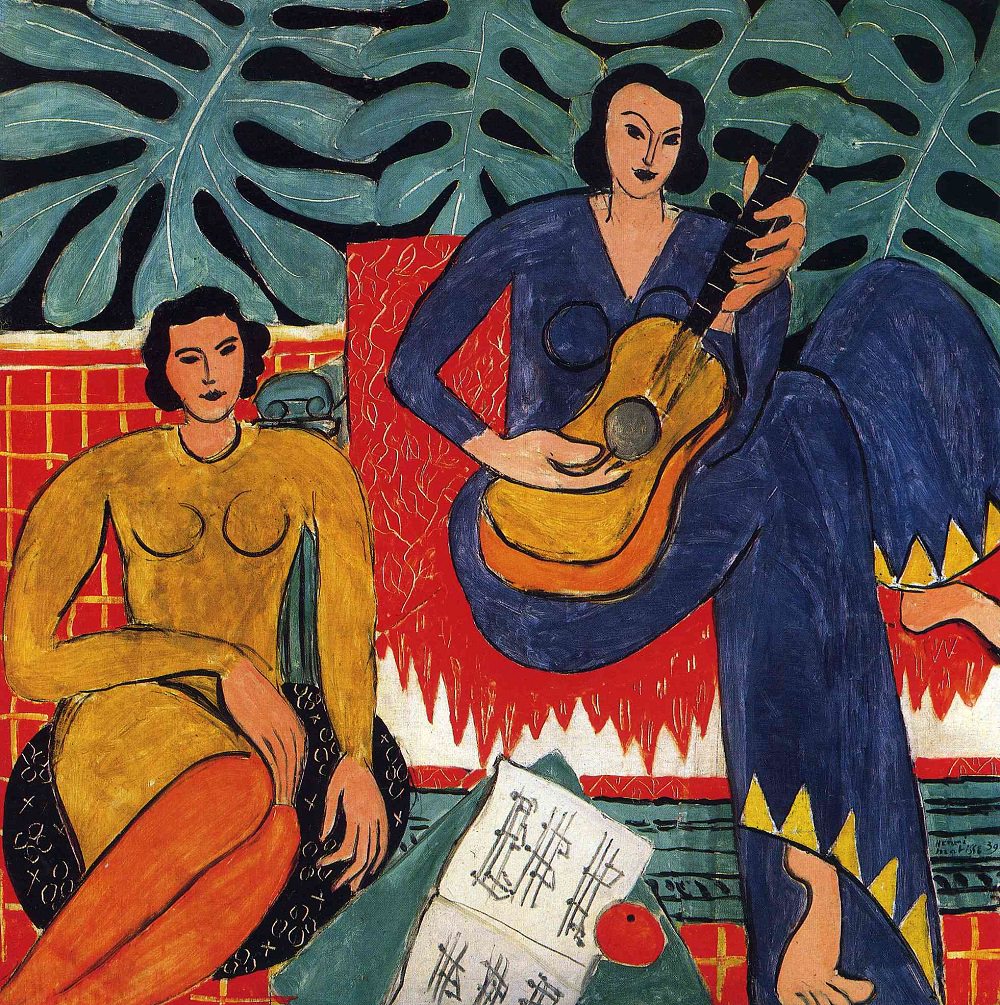

Not all art rebels are “irascibles” as the action painters were once called. The show will include Miro’s “best painting,” the thickly-populated “Carnival of Harlequin,” a major statement of surrealist sensibility at its most playful. Also, there’s Henri Matisse’s gorgeously idiosyncratic sense of line and color in “La Musique,” depicting two seated women, one playing a guitar. Another way of understanding Matisse’s disarming music-lovers as rebellion is to consider it was painted in France in 1939 — with Hitler’s Nazi invasion looming. Such embracing of unfettered beauty becomes an act of joyous defiance, especially as the Nazis would deem most modern art as “degenerate.”

Which brings me back to Pollock. My composer friend Frank Stemper commented on Facebook that Pollock helped inspire his own music-creation because the painter “is so musical.” Then Frank asked, why is this so? My answer: He’s musical partly because, unlike most painters, Pollock virtually danced while he created his drip paintings, because he used the rhythm and pulse — and the lyrical feel — of that whole bodily gesture, to paint. Or more precisely, to make the paint dance, and fly! Pollock understood the liberating qualities and power of the inner musicality of dance.

“La Musique” oil on canvas, Henri Matisse, 1939

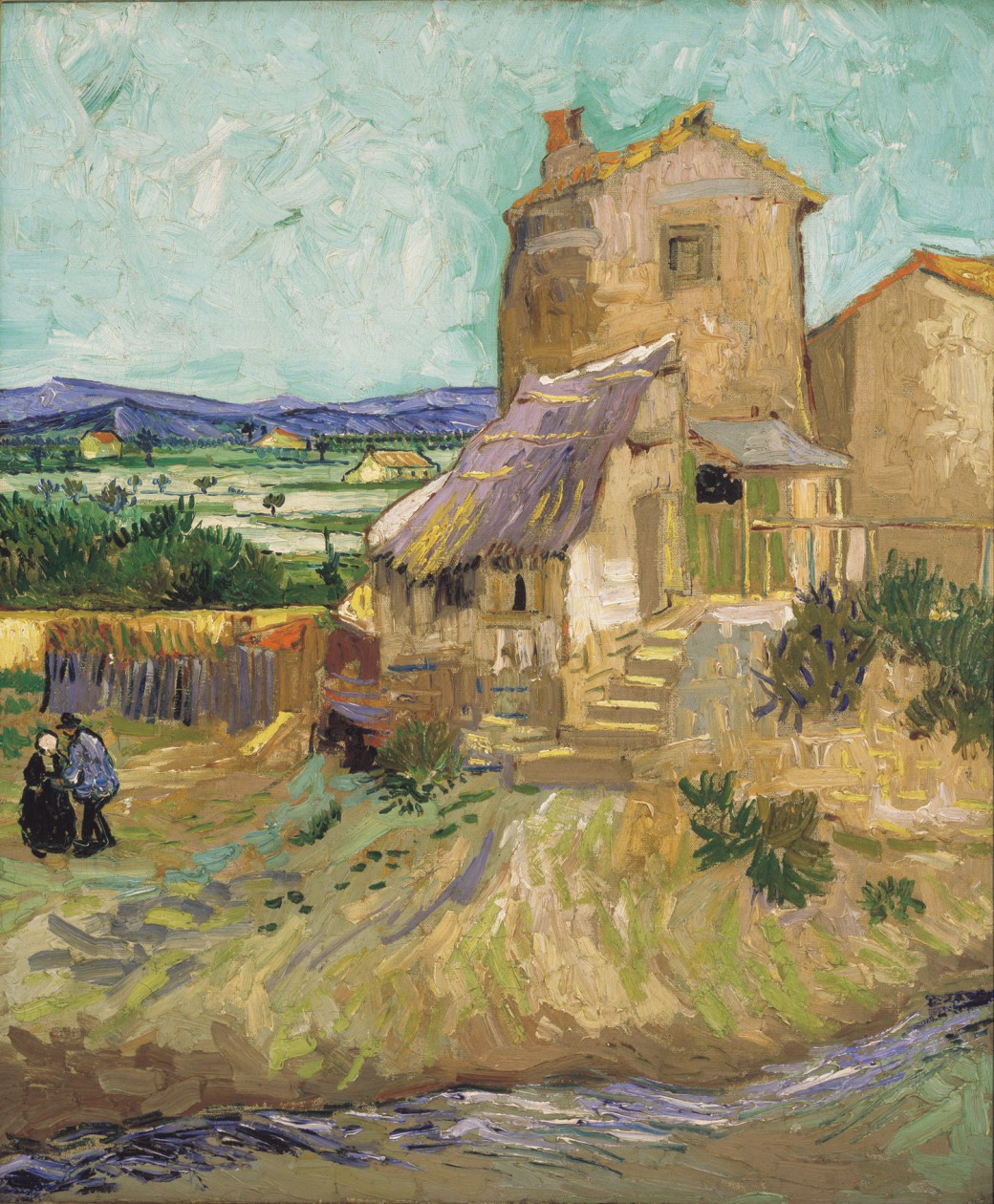

And this also helped Pollock process his demons. Much earlier the anguished genius Vincent Van Gogh found his own way, on the front end of the show’s historical spectrum. Before him, artists rarely attacked the canvas with such raw gusto or expressive directness, so the emotion in the brush gestures communicated as much as the depiction of the scene, as in “The Old Mill” from 1888. “Modernism is also the invention of style as personal expression.” Roberts says.

“The Old Mill,” oil on canvas, Vincent van Gogh, 1888

Modernism’s roots rise from 19th century Romanticism, Roberts notes, but it’s also a response to the industrial revolution. An explicit example referencing that revolution in the show will be Robert Delauney’s 1913 “Sun, Tower, Airplane,” a cubist evocation of The Eiffel Tower, a Ferris wheel and an airplane, “three modern inventions that defied gravity,” Roberts explains.

“So, in 1913, there’s a sense of a sort of utopian future, and that artists are leading the way. Kandinsky, who’s is also in the show, was writing about this, saying the best artists, like Picasso, were seers and prophets who understand that the world was going to change, and it’s going to be this glorious new thing.

“Of course, World War I happened, and that ended the utopian euphoria for industrial vanity.”

“Soliel, Tour, Aeroplane (Sun, Tower, Airplane),” oil on canvas, Robert” Delauney, 1913

Nevertheless, modern artists continued as seers and rebels, even against the recent standard of rebellion, as 1960s pop art rejected abstract expressionism.

Among the still-underappreciated great modernists in the show is the Armenian-American Arshile Gorky, a key link from surrealism to abstract expressionism. Visitors will see arguably Gorky’s greatest work, “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb” from 1944 (pictured at top), “a big, luscious, beautiful painting,” Brady says. I can vouch first hand for Brady’s characterization of the Gorky, having seen it in a Gorky retrospective in New York.

***

Brady also sees striking parallels between the Albright-Knox and MAM – including visionary collectors. The core of Milwaukee’s permanent holdings is the Mrs. Harry Lynde Bradley collection. In the early part of the 20th century, Albright-Knox had a trustee named Conger Goodyear who sensed modernism’s growing dynamism and started bullishly collecting. He began by acquiring a “classical” blue-period Picasso, “La Toilette” from 1906. The painting faced controversy upfront from conservative board members for displaying a female nude so forthrightly. Later, the generous donor Seymour Knox would crucially help the gallery gain its world-class modernist heft.

Also, the Buffalo facility is presently, like Milwaukee’s, building a major addition to house and present its expanding collection. The construction shut-down of the Buffalo galleries is why their collection is touring, Roberts says.

The show will also include major works by Marc Chagall, Paul Gauguin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Frieda Kahlo, Robert Motherwell, Marko Rothko, Salvador Dali, Richard Deibenkorn, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Alberto Giacometti and others.

______________

All images courtesy The Albright-Knox Art Gallery and the Milwaukee Art Museum.

This article was originally published in a slightly shorter version in The Shepherd Express.