Jim Glynn served as best man for my second wedding to Beth Bartoszek, in Madison Wisconsin, at the Unitarian Meeting House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Photo by wedding photograper. All other photos by Kevin Lynch

Without the power of his legs, Jim Glynn often seemed to soar through life on wings of passion, love, charisma, and a gift for serenity. He was perhaps the most extraordinary man I’ve ever known to call a friend.

I’m honoring him on the anniversary of his death, October 18, 2004. Coincidentally, I myself became disabled that same year, but in my upper limbs, with a severe neuropathy that continues today.

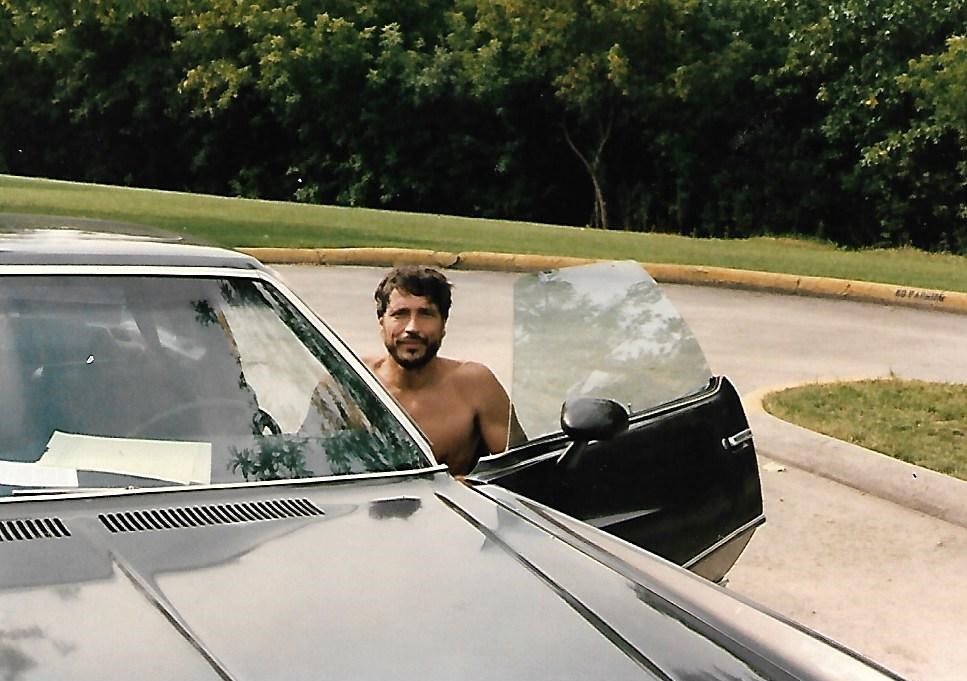

So, it wasn’t until the year he died that I could perhaps begin to fully relate to the challenges that he overcame with rare and inspiring grace. But it’s always different when you are no longer ambulatory. Jim never simply fell back on the use of a wheelchair, as he regularly used crutches for decades, bolstered by the strong athletic upper body that he kept in superb shape as a swimmer and arm-powered cyclist. “He was a marathon swimmer,” said Harvey Taylor, the poet and singer-songwriter with a truly amphibious relationship with Jim. They swam in the Racine quarry together hundreds of times. “He was a magnificent athlete.”

I too swam with Jim in that quarry, which he seemed to especially value for the serenity that its glasslike water surface signified. 1 And yet he often also swam across Elkhart Lake, which can get feisty and treacherous.

Jim gets ready to take a swim in the Racine quarry, a favorite refuge of his.

Harvey may have been Jim’s best friend, but I held him as dearly a friend as any person I’ve ever known. He was the best man at my second wedding. Jim and I bonded over our love of music, with tastes that were similarly wide-ranging. I met him when I was working as album buyer at Radio Doctor’s “Soul Shop” at Third and North Avenue, in Milwaukee, back in the mid-1970s. 2

Only the hippest white music lovers frequented the soul shop, in the “downtown” of Milwaukee’s inner city. Jim knew and loved jazz — our greatest shared passion — as a connoisseur, but without pretension. He also craved classical music, from baroque to contemporary, and had a supremely selective taste for the best of all American vernacular musics, as well as emerging world musics.

An avid fan of many musics, including avant-garde Jazz, Jim Glynn (left) joins a reception at the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music for the renowned jazz pianist Cecil Taylor (center in sport jacket) along with Cecil’s longtime friend and collaborator Ken Miller, with hand around Taylor.

And despite his apparent physical limits, Jim often seemed capable of morphing into multiples of himself. He showed up at most every notable music event in town. After attending maybe three events in one evening, he’d say, “Well, we did it all, tonight.”

What did I learn from him? One thing is this. More than I, he also gravitated to the sort of musically unadorned kinds of music that emerge from Eastern classical music partly because, perhaps once he became paraplegic, he became a hand drummer like the great Indian tabla players. I’m talking about so-called New Age or what mutual musician friend Mitar Covic called “bliss music.” The harmonic simplicity of “New Age” can be traced somewhat to the modal music of John Coltrane, as well as Eastern classical music. But I felt the new music often insipidly exploited those modalities without their profundities and passion, at best turning potential beauty into prettiness.

Now perhaps I can see more Jim’s perspective, throughout his decades of disabled suffering. He always strove for healing, replenishing and enlightened serenity in life, and that included artistic vibrations. Amid contemporary life’s onslaught of stresses and ugliness, his search for musical beauty and rhythmic vitality, which some of the NA musicians achieve, is something I can still learn and benefit from. It ties in to Zen disciplines and meditational practices, the latter which I have partaken off since college, but with no consistency.

Jim may be imparting a tidbit of wisdom to girlfriend Yovanka Dajkovic in this scene (top photo) from Holy Hill in Wisconsin’s Kettle Moraine. In the lower photo, the two of them wave picturesquely from below the great cathedral’s tall steeples.

Jim might have been a “guru” of sorts, though I never realized that at the time. But the man’s rare, aura, his alluring friendliness frequently suggested a tacit invitation to most anyone into his life, to do what he often did with his best friends: Hang, talk, listen and do little jam sessions with a few hand drums and some of his flute playing thrown in. The meditative quality of a Jim Glynn hang-out was often generously enhanced with marijuana. Yet, in later years, he bemoaned the diminishing experience that blended music, camaraderie and marijuana had provided. “I really miss the transcendent experience of a great high,” he said, something that, for whatever reasons, changing times stole from him. Perhaps we had less sense of discovery and revelation after hearing so much music, as well as the oft-discussed damaged idealism and and fading visions of our generation.

The last photo I took of Jim, (playing drums, at far right) at a farewell party for him before he moved from Milwaukee to Portland, Oregon. The other players include (L-R) percussionist Tony Finlayson, pianist Steve Tilton, and harmonica player Steve Cohen (of the blues band Leroy Airmaster). .

But the fact that he could attain such transcendent moments long after he lost the use of his legs speaks volumes for the man’s spiritual capacities. That’s something that people seemed to intuitively sense from him, as he was one of the most effortlessly charismatic people I’ve ever known. It’s as if he made something of his seated posture, implicitly inviting many a stranger into an imaginary crib. So he befriended people time and again, and quickly called them “brother” or “sister,” often before he really even knew their name.

A good-looking Irishman with a low, naturally-seductive voice, an easy smile and a sly wit, Jim was something of a ladies man. Any number of women over the years eagerly befriended and romanced him, while activating their caretaking instinct. Perhaps his best and most loyal woman friend was Pat Graue, who ended up honoring his wish that his ashes be strewn in Sedona, Arizona — with its mysteriously looming rock formations, like permanent sentinels of ghosts — which he considered the most Nirvana-like place in America.

The other end of Nirvana on earth was the hellish day, during the Vietnam War, when his Army jeep swerved in the French Alps, to avoid a blocking car. Flung from the vehicle, Jim fell hundreds of feet, but somehow survived, though this leg functions did not.

For me, he is now a quietly great figure who built up a strong and loyal following of listeners on his mind-expandingly eclectic music programs on WUWM and WMSE radio. And this greatness he wore with the grace of a bird’s wing. The quote of Harvey Taylor above is from Amy Rabideau Silvers’ superb obituary on Jim in The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel upon his death. Reading it again, I’m amazed at the humility of the man, despite all that he added up to, which seems now the essence of cool. Some of the most remarkable aspects of his life detailed in Silvers obituary were revelations to me, even though I thought I knew Jim intimately for over three decades.

For example, while in the service he worked in Army intelligence, including the Cold War’s most famous espionage event. He tracked U-2 spy plane flights by pilot Francis Gary Powers, including the one in which Powers was shot down and captured by the Soviet Union in 1960.

And despite our shared love of jazz, he never told me that long ago, as a fully functioning drummer before his accident, he had played with Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Johnny Cash, and the Everly Brothers when they would visit Wisconsin.

On that October day in 2004, my mother called to tell me Jim was dying. I was living in Madison and jumped on a Badger Bus to meet my folks (also great friends of Jim’s) at the Milwaukee bus station. When I got there, they told me he was gone. Harvey had been there with him. I melted into tears.

Jim bequeathed his huge CD collection to me. I couldn’t practically accept it, as my own collection was nearly as big already. But the gesture deeply moved me. After being cherry-picked by me and a couple friends and WMSE disk jockeys, the recordings were donated to that radio station by his sister .

Something of a philosopher, Jim also helped counsel paraplegic veterans in Milwaukee, Chicago, and Washington D.C. in how to “take a fall and get back up” as his brother Steve Glynn explained to Silvers. That included, “you can still have an active sex life.”

I’m sure he delivered that assurance with an offhanded air akin to Paul Newman’s title character in “Cool Hand Luke,” with “that old Luke smile.” Like Luke, Jim Glynn lived in a sort of prison, but he could break away from that trap with the same kind of uncanny ease.

(One of three post parts on Jim Glynn)

_____

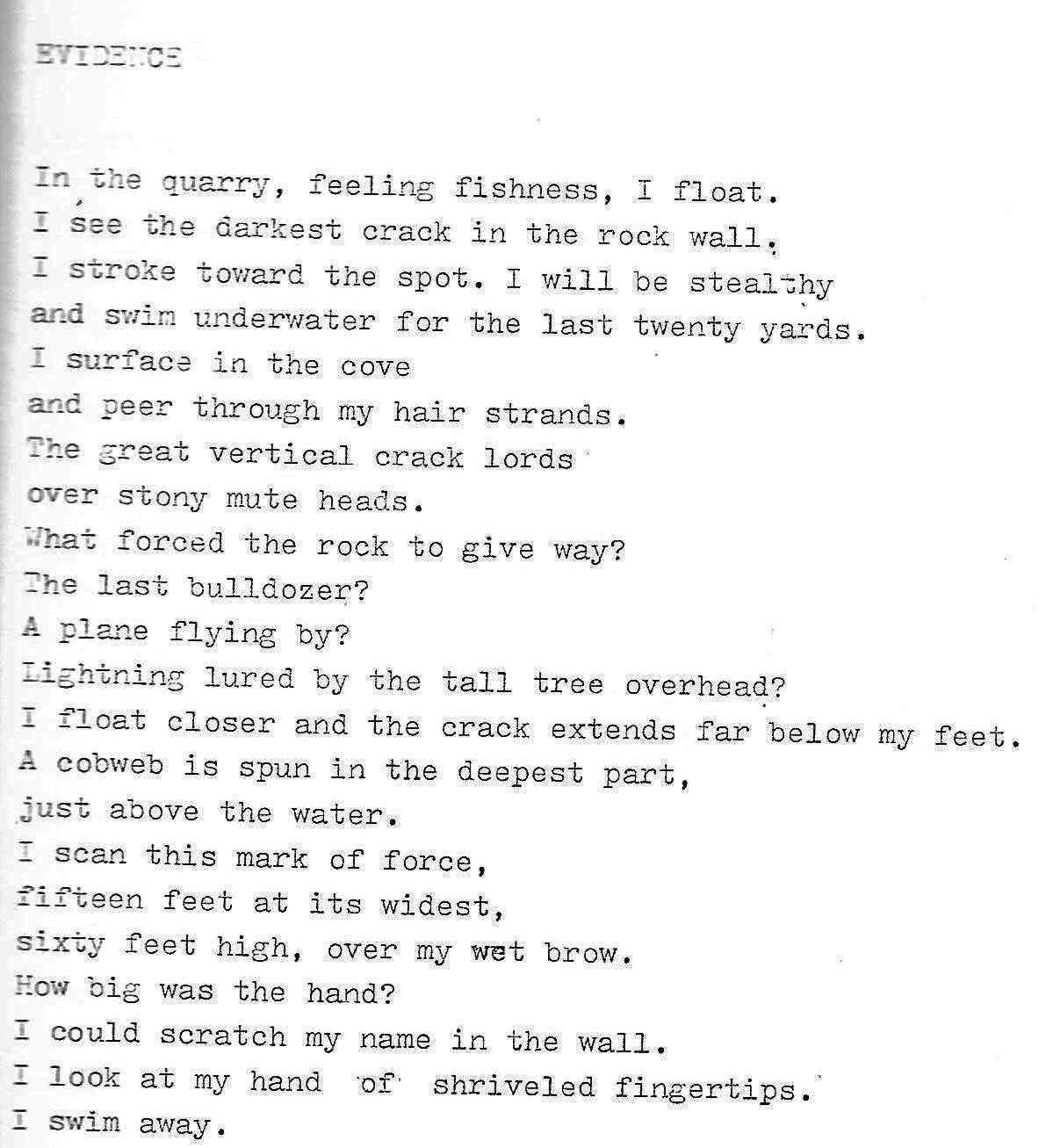

1 Our Racine Quarry swimming inspired a poem I wrote in about 1985. I would never had such an experience of nature, and nature interrupted, but for my friendship with Jim Glynn.

2. Jim actually knew two of my six sisters before he met me. He became a great Lynch family friend — my parents were big jazz and classical music fans — and attended a number of our family’s Thanksgiving meals. In the photo below, he’s seen with his girlfriend Pat Graue in the foreground. (Pictured, L-R, Norm Lynch, Nancy Aldrich, Erik Aldrich, The Turkey of Honor, Lauren Aldrich, Jim Glynn, Pat Graue, and Anne Lynch).

(Pat Graue now goes by the name Zoe Daniels)