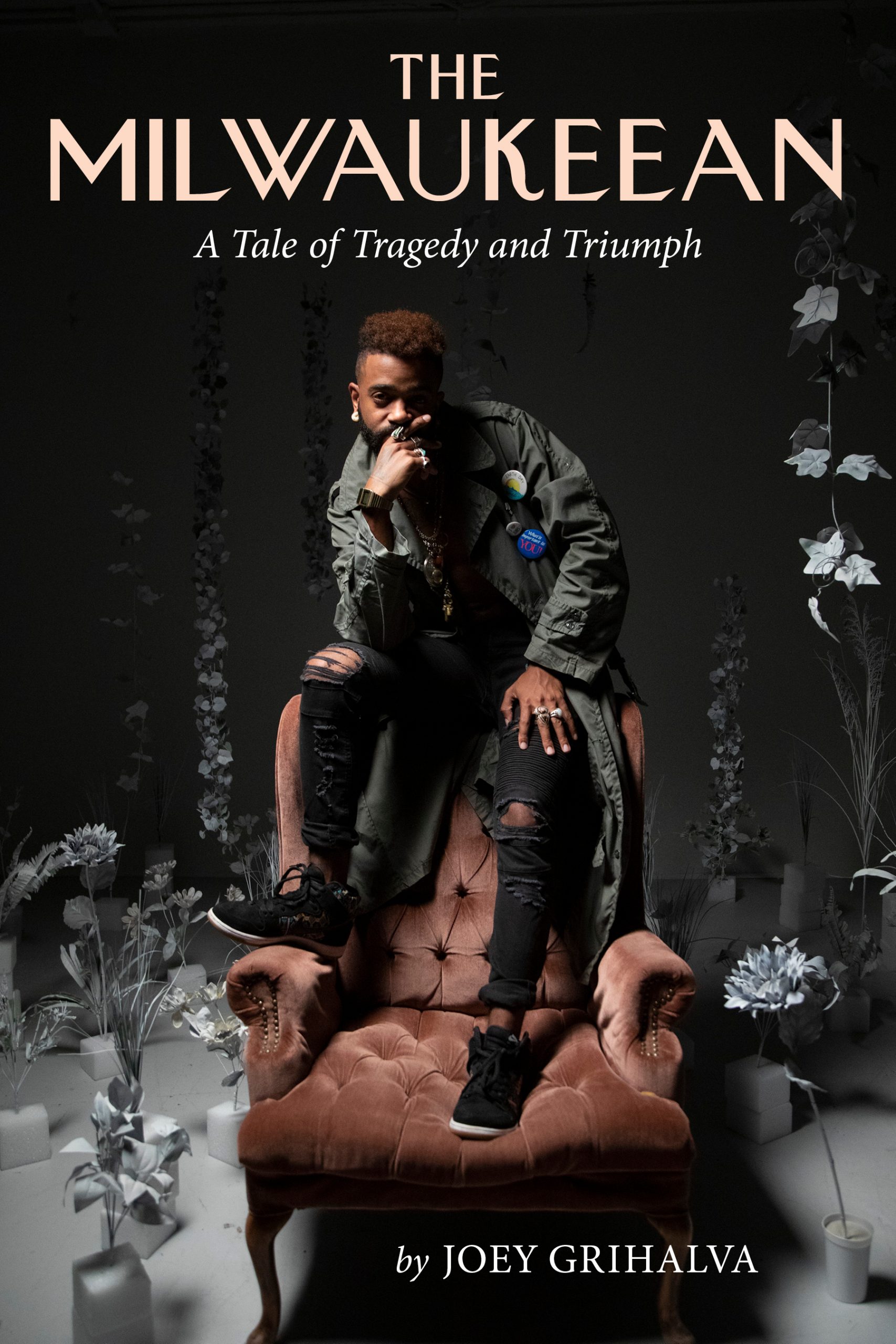

Book review: The Milwaukeean: A Tale of Tragedy and Triumph by Joey Grihalva

Joey Grihalva will present SONSET — a book reading by the author and solo improv by Klassik — for The Milwaukeean, at a new venue, forMartha, 825 E. Center Street, from 7 to 9 p.m. Saturday. The event will follow the Center Street Daze street festival. Cover is $10, or $25 with book.

Is a thirty-ish hip-hopper with only regional renown worthy of a biography? In his new book about Klassik (Kellen Abston), author Joey Grihalva forges, in effect, a freshly painted, still-mutating portrait of a creative man, of Milwaukee and of contemporary times, with all the urgency and potential for tragedy and agency that all implies. In that sense, Klassik emerges as a comparatively humble embodiment of a Black Milwaukeean, even as he manifests genius that might characterize the city. The painfully enlightened and haunted saga – he watched his father die of bullet wounds at age 11 – bends toward the arc of triumph, if justice remains elusive.

The victory comes, in one sense, because the personal is still political. Klassik is one of many who’ve grown as the art of hip hop has grown – fitfully, defiantly, and dynamically – to where Kendrick Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize in 2017. If there’s a connection, Klassik has much more in common with Lamar’s 2015 jazzy masterwork To Pimp a Butterfly than with Lamar’s ensuing album Damn.

It might also be the cultural difference between Compton, California and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Maybe, ultra-hipness vs. a kind of ultra-hopeness? As in “keep hope alive.” As this book reveals, Klassik’s deep troubled history with, and vision of his hometown, sets him apart. It’s partly why he’s watched many Milwaukee area rap artists become bigger names than him.

Standing over his hometown’s skyline, Kellen “Klassik” Abston says he thinks of Milwaukee as a character more than a place. Photo courtesy Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

That does not mean they’re better. That’s why, among increasingly aware Midwesterners, Klassik is as essentially Milwaukee as contemporary hip-hop gets. Grihalva captures a nearly lost Midwestern bonhomie, a pan-racial faith in humanity, hidden beneath the grime of post-industrialism and the crime of racism.

Klassik, who studied jazz saxophone with Milwaukee master Berkeley Fudge, was an early musical prodigy. To the degree he manifests his own filtered amalgam of jazz, classic R&B, and hip-hop, I hear and feel how much he makes good on the thoughtful presumption of his name, Klassik. His previous album, American Klassiks, demonstrated how he can reinvent classics of American vernacular musics, and make them present, alive for today and pointing a beacon forward, musically and spiritually. The artist in him won’t do it any other way.

“This is the problem with Kellen’s stuff – it’s too smart,” says his friend Jordan Lee, a DJ, and a former station director at 88/Nine Radio Milwaukee, who’s also a member of the jazz-hip-hop trio KASE, with whom Klassik as recorded and collaborated. 1 “It was never going to work at the beat battle,” referring to a competitive hip-hop event Lee produced from 2005 to 2015, known as the Miltown Beatdown, which brought together produces rappers, and hip-hop heads from all over the city.

Rather than always “on the beat,” that can be as delimiting as it is compulsively attractive, Klassik’s music unfolds with an almost Midwestern shapeliness, as if informed by the Kettle Moraine as much as by the staccato pulses of the urban environment. As a primal Klassik source, I’ve always heard the soul-praying-to-the-moon existential angst of Marvin Gaye, whom he shouts out on “Black-Spangled Banner,” on American Klassiks, recorded live late one night in Bay View’s Cactus Club.

Klassik’s expressive power dates back to, among other things, Marvin Gaye and the hauntings of his childhood. Courtesy IAMKLASSIK.com.

He’s also decidedly more improvisational than most hip-hop or pop. “Maybe it’s the jazz purist in me,” he muses to Grihalva. “When you think about live music and playing an instrument, even the most rehearsed and refined part has its own idiosyncrasies or little inflections that make it human. I’m making something, I’m adding layers and depth.” 2

Klassik performs at Pianofest, at the Jazz Gallery Center for the Arts, a few years ago. Singer Adekola Adedapo recalls, at age 10, Kellen played “Over the Rainbow,” on saxophone at a Heath Brothers jazz workshop at the Wisconsin Conservatory, one of the first discoveries of his talent. Photo courtesy JGCA

The book, a prime example of “new journalism,” is also the author’s own story, about his relationship to his subject and their shared hometown, “an eternal tie that binds.” Abston and Grihalva are virtual contemporaries and Grihalva teaches at Milwaukee’s High School of the Arts, which is Abston’s alma mater.

Part of Abston’s burden is that he feels he could have done more than simply freeze up, to possibly save his father from dying, and that, 20 years past, Robin Abston’s murder remains unsolved. That’s plenty to drive a young man to drink and drugs – a large part of his struggle, aside from his often-exquisite peculiarity as a young, gifted, and black man, within our race-obsessed culture. And yet he won’t leave Milwaukee, as partly a spiritual detective still on a homicide case grown cold for most others. His relationship with police is deep ambivalence, hardly hatred. But he’s also doing close investigation of his own identity, which messes with him, with ghosts of what he’s been, shouldn’t be, won’t be, and can be.

Klassik’s bling always includes the dog tags of his father, veteran Robin Abston, who was murdered 20 years ago, in a crime that remains unsolved. Courtesy Milwaukee Magazine

Ultimately the redemption and triumph of the story is the hard-earned wisdom that arises from it, in the experiences and voices of both author and subject, as well as a choir of street-sage homies. The way that choral mosaic enlightens the story, like a vast stain glass window, is Grihalva’s achievement, his crafting of a sense of authenticity by finding common cause with your roots. One of Klassik’s defining ventures into communal creativity was his key role, in the summer of 2016, in Milwaukee’s Strange Fruit Festival, named for the searing anti-lynching song “Strange Fruit” popularized by Billie Holiday. The festival was spurred in response to two police killings of unarmed black men on back-to-back days: Alton Sterling in Louisiana, and Philando Castile, killed in his car in St. Paul Minnesota.

“That was one of the first times where I felt pulled artistically, in terms of feeling a responsibility with my platform,” Kellen explained. “It heightened this desire to wield it, almost like a weapon, for good.” His profile was rising, as he was performing in New York City during the first two nights of Strange Fruit. Kellen flew back to Milwaukee for the final night of the festival.

Then, that weekend’s Saturday afternoon, Milwaukee police shot and killed Sylville Smith in the Sherman Park neighborhood. The incident sparked riots that culminated in the burning of a gas station, a bank, and a beauty supply store, images seen on international news the next morning.

And there, defying hell-on-earth fury, Klassik and friends conjured a lifeline to redemption. “Everybody was on their A-game…It was such an amazing event,” he says. “You could tell everybody was there for the betterment of the community in whatever small or large way they could. And was just crazy timing that we had this festival amid the madness that ensued.” The event played again the next two years, and Abston wrote a manifesto for a potential relaunch of the festival, though it never got off the ground.

Much chaos and transformation has come down since then, the era of Trump and George Floyd, and Klassik has achieved a kind of personal-is-political triumph of textured passion on his last album QUIET, with assists from Milwaukee artists who’ve gone to greater renown, SistaStrings, the nationally celebrated singers-string-players, and folk-rock artist Marielle Alschwang, among others.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about protest in the form of joy, specifically Black joy,” Abston says. “With the new stuff I’m working on, there is this element of defiance in being happy and free. That’s like the most powerful thing you can do as a minority in this country.”

The power, he understands, also derives from accepting himself as a Milwaukeean, “The Milwaukeean.” He’s lucky to have a biographer as attuned as this one, who can tell his story so tenderly and beautifully. Abston reflects on the notion of faith: “If I hit a good note or I’m writing a good melody or these chords have a certain color or have the ability to stir up emotion from thin air, that’s magic. That’s God. It’s all those things. It’s being connected to something greater than ourselves.”

Almost two years ago to this day, he meets with Grihalva at high, windswept Kilbourn Reservoir Park, which overlooks downtown where North Avenue curves into Riverwest. It’s one of his favorite places in the city. “I would go up to that hill over there when I was super-fucking depressed. I would just sit and cry, let it out and wipe them tears off. Then this warmth would come over me, especially at night. Something about the lights. It’s weird because it’s not a spectacular skyline. But it’s mine, you know?” He continues, “In all my videos, I’ve always thought of Milwaukee as a character, not a location.”

That idea of making a city a living, breathing character – a father figure? – seems to speak volumes about Klassik’s genius, as an archetypal son of a quintessential American city, in all its grit and glory, it’s patriarchal sorrow and shame, its defiant brotherhood and sisterhood.

________________

- Klassik’s most recent appearance on a recording is his largely wordless vocalizing on KASE + Klassik: Live at the Opera House, on B-Side Recordings.

- Grihalva’s previous book was Milwaukee Jazz, a photo history from Arcadia publishing’s Images of America series.