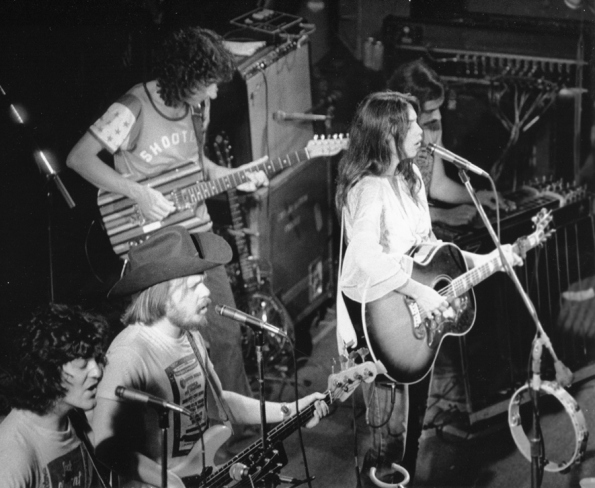

Emmylou Harris and somewhat shadowy Rodney Crowell on the current “Old Yellow Moon” tour. Courtesy bigandbubba.com

This is a mystery story of sorts, with a twist or two, yet the mystery’s not impossible to solve.

The question: Why Rodney Crowell is still emerging from the shadows, even though he ranks among the most esteemed singer-songwriters in Americana music today.

I maintain he’s a singer-songwriter comparable in talent to Steve Earle or Lucinda Williams, or in the conversation with a Townes Van Zandt (a big Crowell influence), even if he isn’t quite as prolific as those during their peak years.*

I begin my investigation by observing that the craggy depths of American roots music are complicated by its purveyors’ regard for seemingly well-worn vernaculars intertwining with their respect and appreciation of their stylistic forebears.

The concert this Tuesday at the Pabst in Milwaukee featuring Emmylou Harris and Rodney Crowell, and Richard Thompson exemplifies the circumstances.

It’s also one of the most noteworthy Americana music concerts to hit this town, at least since we saw Gillian Welch and David Rawlings last July and, in 2008, Harris with another old male crony collaborator, Buddy Miller, along with Shawn Colvin and Patty Griffin.

Although the concert opener Tuesday, Thompson is easily a worthy headliner as arguably the greatest living British singer-songwriter guitarist, working in an even older-rooted Celtic folk-rock idiom –part of the historical continuum that informs Americana music.

You get a great example of his concert chops in the DVD Richard Thompson Live from Austin, Texas, with Thompson tearing it up on Austin City Limits. The video includes many of his best songs, including “Shoot out the Lights, “”Mingus Eyes,” “She Twists the Knife Again” and “1952 Vincent Black Lightning.” He has a new CD Electric, produced by Buddy Miller, which I haven’t heard. 1

The dedicated and exquisitely gifted Harris was recently deemed by Alternate Root.com as America’s number one female roots music singer.

So it is Crowell who remains a comparative mystery to the vernacular’s newcomers, among Tuesday’s three featured performers.

An inspection of his career and especially of his songwriting helps underscore the opinion of Tamara Saviano — that Crowell is as eloquent as anyone in the blooming roots music phenomena. I’m sure his answer to a question about the extraordinary popularity of the British purveyors of Americana, Mumford & Sons, would be enlightening. Saviano should know, being a Grammy-winning producer of ambitious, probing All-Star album tributes to the songwriting of Stephen Foster and Guy Clark, and former president of the Americana Music Association.

But more germane to this concert, Crowell’s collaboration with Harris is somewhat of a commentary on his career, which has never received its due even as Harris is one of two famous singer-songwriters who have helped define his life, and unintentionally overshadowed it.

He got his first break in1975, when Harris hired him as a backup singer and guitarist in her newly formed Hot Band. She’d embarked on a solo career after being shaped by the primary influence of the tragically deceased Gram Parsons, who gave Harris her break in the business.

Rodney Crowell (far left, ca. mid-’70s) performing with Emmylou Harris in the Hot Band. Courtesy bobkinney.com

So I investigate the mystery of Rodney Crowell by way of her current collaborator, because there must be good reasons why he ended up with her at this point in time.

I recall a Harris concert in the early ’80s at Summerfest in which I stepped backstage to get information for a Milwaukee Journal review and stumbled upon Harris. Instead of hobnobbing with her band or fans and well-wishers, she was sitting alone in virtual darkness on the steps of her trailer. I happened to walk right up to the steps and I stopped, startled by the unexpected encounter with the show’s beautiful star. She gazed into the distance, lost in the summer stars, and though we were alone together she never even turned her head to look at me.

I quietly went my way and have always interpreted her odd remoteness kindly, as reflecting her ongoing and fully acknowledged struggle with the ghost of Parsons. I think that experience also reveals something of the nature of the roots music sensibility, in that many American vernacular musicians have resolved the assertion of an identity apart from their formative roots by actually coming around to embrace them, and redefine themselves via an honest acknowledgment of where they come from and thus, where they’re going.

It would also suggest why Harris commented, in a recent NPR interview with Crowell that “sad songs are her favorite songs.” They are “the most beautiful songs,” she added laughing, almost surprising herself with the answer, and Crowell agreed.

Crowell actually helped fill in some of the void left by Parsons, having the talent requisite, if not the ego and perhaps Svengali-like charisma. 2

Harris, who first made her mark as an extraordinary harmony singer, helps to define the roots music sensibility as well as any artist, in her regard for other singer-songwriters and her voraciously eclectic exploration of the tangled roots of American vernacular music. In fact, she did little songwriting of her own until the beginning of the 21st century and many of her efforts were collaborations with Crowell.

His own career didn’t amount to anything comparable to his talent until his 1988 Columbia records debut Diamonds and Dirt, which improbably produced five consecutive chart-topping hits, including a duet with his former wife Rosanne Cash.

Crowell at the timed explained that one his primary influences was ’60s British invasion rock, of which Thompson was part of the second-wave. Thus, the logic of Thompson on this bill.

So yes, Rosanne Cash became the second huge female talent in Crowell’s life.

Crowell and Cash went their separate ways before she became a big crossover name in country music. But each likely enhanced the other’s growth as among the most powerful and literate songwriters of their generation. Aside from her stellar music career, Cash has written a collection of short stories and a memoir, both very well received. And a few years ago Crowell published his critically acclaimed memoir Chinaberry Sidewalks.

The mind reels at what might’ve emerged from a maritally informed writing collaboration between Crowell and Cash.

Nevertheless Crowell, backpacking his relationships with two remarkable women, embarked on his own solo career and found his groove quickly. Diamonds and Dirt revealed him as another of the distinctive and diverse breed of hybrids among a generational bounty harvest of Texas songwriting talents.

He stepped out with a bracing country-rock group concept by forming the band called The Cicadas, comprising some of his back-up band members and guest Jim Lauderdale to reach out to the crossover roots-rock audience. My friend and former colleague Eric Schumacher-Rasmussen highlights the band’s sole eponymously-titled album in his blog Soulscratch.com:http://www.soulscratch.com/scratched_into_our_souls/2014/11/the-cicadas-we-want-everything.html

Crowell reached perhaps his creative peak with two albums in the early ‘00s. The Houston Kid in 2001 found him delving deeply his own past with the fearless and cinematic memoir album, which his solo debut had long promised.

Cover of Crowell’s “The Houston Kid” album, courtesy www.allmusic.com

Cover of Crowell’s “The Houston Kid” album, courtesy www.allmusic.com

It’s an unflinching and sometimes harrowing immersion in his dirt poor, rough-and-tumble youth in South Texas, including the heart piercing lyricism of “I Wish It Would Rain”:

“Turning tricks on Sunset 20 bucks a pop /some out-of-town old businessman or an undercover cop/I’m living with the virus slowing way down in my veins/ oh, I wish it would rain.”

Largely contemporary rockabilly and folk, the music always perfectly frames the stories. Equally good is the follow-up album Fate’s Right Hand, another autobiographical collection that fixes just as cold and tender an eye on adulthood.

The several albums since then maintain a high level of poetic incision and musical invention, his last an ingenious collaboration with fiction writer Mary Karr, titled Kin.

And now finally Crowell reunites with his old compatriot Emmylou. On the Nonesuch release Old Yellow Moon, his reedy tenor voice blends with Emmylou’s crystalline instrument for an especially piquant resonance.

This is just what the doctor ordered for both. Harris’ long and prolific career radiates creative courage, resourcefulness and musical enchantment. But her last album Hard Bargain, despite several highlights, felt a bit flat. Crowell’s career frankly needs a boost, given his major league-talent. He admits to have finally “made peace” with his own singing voice which, like many fine songwriters less vocally blessed than Harris, can be an acquired taste.

Old Yellow Moon seems as invigorating as the first rising sun of springtime. The chemistry — that justified the The Hot Band name decades ago — sparks the very first song, the rollicking “Hanging Up My Heart.” Yet they promptly show their range and fluency in a different genre on the ensuing “Invitation to the Blues.” Typical of Harris, this collection exploits an array of gifted musicians — James Burton, Stuart Duncan, Vince Gill — and songwriters, including Hank DeVito’s gritty “Black Caffeine,” the perhaps inevitable nostalgia of Matraca Berg’s “Back When We Were Beautiful,” and Allen Reynolds’ contemporary classic “Dreaming my Dreams” — “I’ll always miss dreaming my dreams with you.”

Yet the crux of the album seems to be Crowell’s own ironic lament “Open Season on My Heart,” which reveals two battle-scarred singers who still carry, and remain vulnerable to, their passions and to life’s cruel vagaries, a realization tempered by self-understanding: “So here’s to the clown down in the mouth/ Here’s to the whole thing going south./ I’d just stay home if I were smart./It’s open season on my heart.”

Crowell may yet see his finest hour. We’re lucky that both he and Harris retain the courage of their convictions and passions, and chose not to stay home.

__________________________

* Crowell’s critically acclaimed discography includes seven four- or five -star album ratings from All Music Album Guide, which pays attention on most music fronts as well as anyone. He also has one Grammy, for best country song in 1989, for “After all this Time.”

1 I defer to Rolling Stone’s fine description of Thompson, in the No. 69 slot of the magazine’s authoritative “Best Guitarists of All Time”: “Shooting out life-affirming riffs amid lyrics that made you want to jump off a bridge, he combined a rock flat-pick attack with speedy finger-picking. His electric-guitar solos, rooted less in blues than in Celtic music, can be breathtaking, but his acoustic picking is just as killer; no one knows how many tears have been shed by players trying to nail ‘1952 Vincent Black Lightning.'”

Read more: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/lists/100-greatest-guitarists-

2. the Emmylou-Gram relationship lives on in current roots music mythology in the recent song “Emmylou” by the Swedish folk group First Aid Kit:

When its you I find like a ghost in my mind

I am defeated and I’d gladly wear the crown

I’ll be your Emmylou and I’ll be your June

if you’ll be my Gram and my Johnny too.

— from the 2012 album The Lion’s Roar.

20111123/richard-thompson-20111122#ixzz2NdYzDAlX

PLEASE NOTE: As of time of this posting, some tickets to the Milwaukee performance of Emmylou Harris and Rodney Crowell with Richard Thompson and his Electric Trio are still available. http://purchase.tickets.com/buy/TicketPurchase?&agency=PABST_THEATER&pid=7416736

Rachel dives to investigate the whales’ situation. Courtesy rottentomatoes.com

Rachel dives to investigate the whales’ situation. Courtesy rottentomatoes.com

“Portrait of the Artist” by Rembrandt ca. 1665. Image courtesy wikipaintings.org.

“Portrait of the Artist” by Rembrandt ca. 1665. Image courtesy wikipaintings.org.