The late Bill Bennett, principal oboist of the San Francisco Symphony

How do you account for the snuffing of such a brilliant flame as Bill Bennett?

I can hardly imagine the heart-lacing travesty of seeing Bennett, the principal oboist of the San Francisco Symphony, collapse with a brain hemorrhage during his performance of the Strauss Oboe Concerto with the orchestra at Davies Symphony Hall on Saturday Feb. 23. He never recovered and died, on Feb. 28. He was 56.

What will haunt me is that I never met Bill, and I should have. After all, he was married to my cousin Peggy Lynch. And it’s been decades since I’d been out to the West Coast to visit my California relatives. My dad’s two brothers, Jim and Peggy’s father Jack, died on the coast during that time.

But Bill’s death is the shocker. Damn.

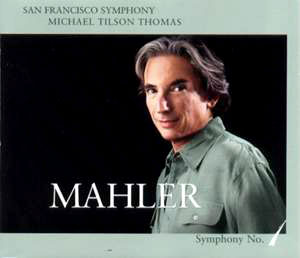

“I am heartbroken by the tragic death of Bill Bennett, which has left a terrible, sad emptiness in the hearts of the whole San Francisco Symphony family,” Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas said in a statement in Berkeleyside newspaper.

“Bill was a great artist, an original thinker, and a wonderful man. He was very generous with his attention and affection for his friends, colleagues, students, and audience members. We all experienced his sunny enthusiasm for music and life. I am saddened to have lost such a true friend.”

Bill was truly the artistic star of the extended Lynch-Bennett family. What’s more, he was a man after my own heart, being a cartoonist and caricaturist, a slightly devilish skill I share with him. He reportedly amused orchestra members with his creations during long road trips.

Perhaps worse, I never heard him perform, at least life. I have heard him play on record, several Mahler recordings, and treasure my recording of him (inherited from my late parents) with the SF Symphony doing Mahler’s First Symphony. Oddly enough, I alluded to Bill (for the first time) and that recording in a recent blog about the Grammys.

For those who aren’t classical music fans, the principal oboist is the prince of the orchestra. He or she usually provides the concert-opening pitch for the string players to tune their instruments to. And orchestral works tend to revolve around the oboe as the one wind instrument that most crucially emerges with its penetrating poignancy and almost seductive fluency from the veils of strings.

As I write, I happen to be listening to one of the most sublime recordings of recent years, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson’s career-defining recording of J. S. Bach’s Arias BWV 82 and 199 (Nonesuch). The chamber orchestra’s oboist is sinuously twining around the mezzo-soprano’s tragically limpid voice as I type — pure serendipity.

I say tragically because Lorraine died way too young as well, of breast cancer at 52, riding a Grammy-winning career breakout.

The San Francisco Symphony has six Grammy awards, including a 2012 Grammy (for a record of John Adams music), one Emmy award (for Sweeney Todd), and presented the world premiere of Henry Brant’s composition Ice Field which would win a Pulitzer Prize, among many other distinctions, which puts them squarely in the discussion of which is America’s best orchestra.

Oddly enough, I alluded to Bill (for the first time) and that Adams recording in a recent blog about the Grammies.

We always struggle to take something away from such senseless loss. It’s like mercury running through our fingers. There’s no crazed gunslinger to blame. Only the ever-looming vulnerability of life, whose corporal presence is always endowed with fatal uncertainty — and inevitability — as much with blinding brilliance, or heroic humanity.

And I still cringe when a plant dies.

I just noticed that, some time ago, I wrote a brief comment next to the translation of the third Aria of Bach’s BWV 82 cantata, which deals with accepting death. The note reads: “How childlike we become.”

The passage, by an anonymous librettist drawing from the Gospel of Luke, reads:

slumber now, you weary eyes,

close softly and pleasantly!

World, I will not remain here any longer

I own no part of you

that could matter to my soul.

Is any of this a comfort at this time? It’s hard to imagine a man of such gifted vitality feeling such weariness and resignation. The text’s turning away, with a temporally unbound soul, rankles sharply, to me as well.

Yet life’s ongoing fugue of passages constantly sends us into degrees of darkness and light and sometimes mysteriously discernible textures. Those deeper auras can allure to where we want to melt right into them, just for the experience.

Sometimes people do take a plunge, perhaps even unwittingly, and sometimes they never return, at least not our way, again. Certainly this can happen in the depths of artistic revelation and outpouring, as artists and writers have testified to for millennia.

Bill Bennett was right out there, in the spotlight producing beautiful art, when the darkness struck. And yet, the light kept rising.

Risking a platitude, I know, it was a fine way for him to depart, if tragic in its premature timing. As my 12-year-old nephew Dillon Lynch mused, “At least he died doing something he loved.”

Now I have Bill’s Mahler One playing, his oboe is rising momentarily, mysteriously, in the ravishingly slow unfolding of the first movement’s central section. The oboe’s call actually slinks up on you as you hear it.

And the powerful thumps and crashes, and the swirling clarion anthem that ensue. Sky piercing! Reincarnation as a free-spirit lightning bolt?

Recall, the human state of creative or artistic fire. It’s electrically mainlined to youth’s unfettered creative core. And if we become, in some way, childlike at our end, doesn’t that spiritual condition bode well for a new childhood and a new life, which always remains unknowable to the earthbound?

What else would a setting soul’s return to innocence mean?

The last time I was with Uncle Jack and Aunt Barbara’s family I was a young man. I spent too much of the visit to their beach house trying to body surf the Pacific waves, with Jimi Hendrix music blaring from the bluff above. It was my first-ever plunge into the ocean, one of those deep-texture experiences. I was down there with two traveling mates from Milwaukee and Cousin John Lynch.

Peggy was young and maybe peered at us with a squint of disdain as we pranced around in her bathing suits.

Most of the best, as well as the worst, memories are of youth revisited.

And that exhilarating, liberating surf is some of what I hear in Bill Bennett’s music now, in the final passage of Mahler’s First — ascending, proudly triumphal, proclaiming life and quite far beyond as his domain, his last, or next, passage. The final thunder unleashes the human lightning bolt, in all his power and glory.

________________

check out this eyewitness report on Bill’s fateful concert:

Very well said cousin. I too am sad to say, that I never met him. It appears he was a very loved individual. May his soul rest in peace and his oboe be heard throughout the heavens.

Very well said, cousin.

Nice piece Kevin!

Dear Kevin,

Thank you for sharing such a thoughtful and meaningful piece about Bill. I know he would have loved it. I wish you two would have met. He would have had so much to say to you.

But who knew we would have him for such a short time? I feel the same way about Mahler’s First and that somewhere he is watching from a triumphant place.

I remember Jimi Hendricks blasted out of speakers from the bluff top for all the surfers. That was John Lynch and he was somewhat of a local hero for

that stereo system!

With love, Eileen

Good to hear from you Eileen. What a loss but what a life! Yes you were old enough to remember Hendrix on the bluff. It was a great time out there with you Lynches. I need to get West again. Give my best to Peggy,

with love,

Kevin

Thanks for the repost Kevin

Glad you noticed that, She.