Martine Gutierrez, “Queer Rage, Imagine Life-Size, and I’m Tyra.” Inkjet print, 2018

Enter “Native America: In Translation” and your eyes and mind open through a revelatory aperture into Indigenous culture of the Americas. The exhibit title may mean various things: translating ingrained perceptions to understand the underexposed art, life, values and sensibility of Native artists to a broader public. Also, it reveals how high-quality, large-scale photography has become an important medium, besides those more associated with Native folk culture. Native artists wield such contemporary art technology as deftly, and often as pointedly, as their forebears did bow and arrow.

Curator Wendy Red Star notes the political implications: “The ultimate form of decolonization is through how Native languages form a view of the world. These artists provide sharp perceptions, rooted in their cultures.”

The cumulative effect is prodigious and nourishing, like an advancing thundercloud over a parched land, addressing decolonization and cultural enlightening of desiccated racist perceptions that once led to dehumanization and genocide of countless tribes. One artist, Duane Linklater, is explicit in a series of photos of a sculpted bust of the nation’s celebrated father, George Washington, which references the story of how he ordered troops to slaughter an Iroquois tribe in occupation efforts in 1779.

Most of the work serves strong aesthetic and well as symbolic or narrative values. For example, perhaps the edgiest artist is Martine Gutierrez. Queer Rage, Imagine Life-Size, and I’m Tyra shows an extravagantly adorned lounging woman seated in a dazzlingly colorful, almost magic-realism tableaux that asserts her identity—and her rage in the form of a Black Panther inserted collage-style—as endemic to this scene of natural American bounty. Gutierrez, a tall, striking trans woman, is the model in most of a series of hypothetical slick fashion magazine layouts, because she believes she cannot be hired as a model in such mainstream magazines.

Rebecca Belmore also celebrates her culture while delineating some of its rude limits in American society. She honors a tribe Matriarch in a large silhouette portrait of a woman posing in a ravishingly sumptuous gown bedecked with crimson roses.

Rebecca Belmore, “Matriarch,” inkjet print, 2018

By contrast, with Keeper, in black and white, Belmore shows a lowly laborer woman scrubbing the mud off a large outdoor patio, likely owned by a wealthy employer, her clothes caked in mud. Her posture, semi-prone sideways on one hip, recalls the woman in Andrew Wyeth’s famous pathos-laden painting Christina’s World. Wyeth’s subject, a neighbor of his, was physically challenged and often traveled around her home by crawling. Belmore’s groundskeeper has normal laborer’s abilities, though she’s reduced, like Christina, but by demeaning work. Yet Belmore lends the woman dignity by setting her in the foreground of an elegant composition, with a deep perspective on the concrete floor, and its brickwork pattern receding into a cloudy distance.

Another artist, who works brilliantly in black-and-white only, is the Ecuadorian Native named Koyoltzintli. Her aim is far wider than the more pointedly political. She’s aiming for the moon, by poetically inquiring about the relationship between humans and our most seemingly lifeless environmental form: rocks, boulders, and large rock masses, with a sense of wit and wonder.

I don’t recall another artist making this kind of conceptual connection which, at a glance, seems to incongruously mate the living form and the seemingly static one. Yet, in black-and-white, her nude models, ingeniously implanted into the scenes, nearly acquire the stone-like quality of the rock masses they lounge on, somewhat like surreal Odalisques, on the verge of melting into stone.

Koyoltzintli, “Gathering Roots Up in the Sky,” inkjet print, 2019

For example, the two women at the top and the bottom of the large vertical cavity in “Gathering Roots Up in the Sky,” seem like oddly elegant rock formations courtesy of the collective artistry of wind, water, and sand, crafted laboriously over perhaps millennia. Yet there’s no trace of sky visible – unless the blackness within the large cavity is the night. “Koyo,” as she is nicknamed, has a knack for enigmatic titles.

An even more extravagantly beautiful image is her “Misunderstanding of Raven,” In a note to the reviewer, the artist explains the title only by saying it refers to the name of the model. So apparently the same model (with time-lapse trickery?) assumes two separate poses. Both women, adorned only with the wind, are perched, in tantalizingly faint abstraction, atop a fascinatingly textured rock mass, like sirens singing to the sky, luring the ever-vulnerable winged god Icarus (or the Native American equivalent thereof) away from the sun to a different, yet possibly as fateful, destiny. As for “misunderstanding,” let your imagination catch Koyo’s windblown drift. “Misunderstanding” may even lead to surprising insight.

For all that, the rock formation below, which comprises most of the composition, is a sinuously organic maze. It’s a rare instance of “dumb” rocks almost upstaging nude models. In all of Koyo’s works here, one is forced to reconsider the possibility of some manner of life contained, more than figuratively, in the myriad of evocative rock forms that inhabit the planet. To perhaps lean down to listen to a rock sometime. Is that faint, earthy rumbling in the distance, or right at my foot? And to reconsider humanity’s primal and current relationship to such humble, if sometimes mountainous, forms. 1

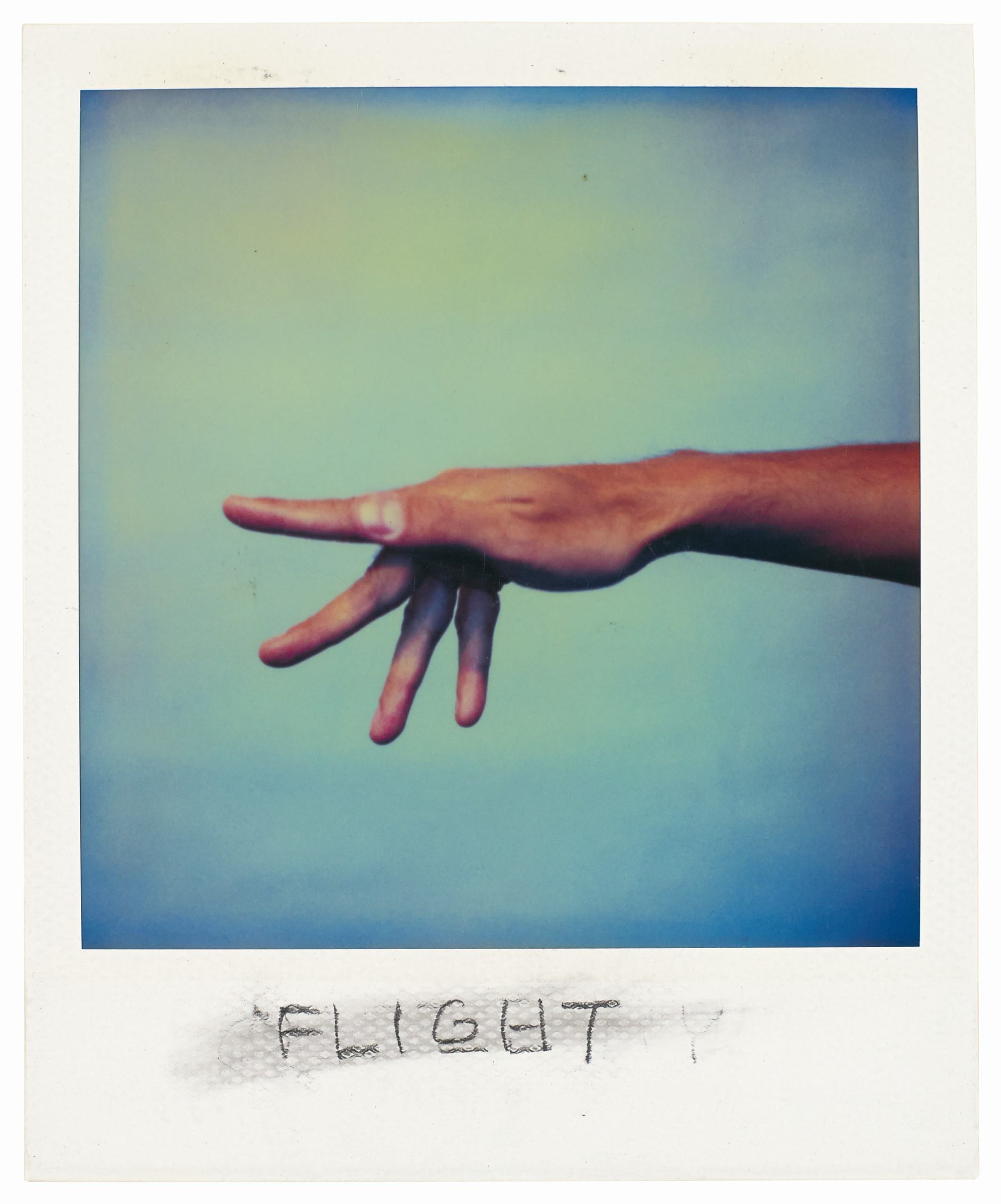

Another artist with seemingly modest yet expansive vision is Kimowan Metchewais, who offers a photo sequence of hands entering the composition from the right, illustrating words in “hand language” of his tribe, perhaps derived from covert signaling of guerrilla-style Native American fighters during the 19th century.

Kimowan Metchewais (Cold Lake First Nations, 1963–2011), “Indian Handsign,” Dye diffusion transfer print, 1997.

The splayed fingers of “Flight” (image at top) deftly mimic a bird’s soaring wings, but the whole sequence of images also suggest, for this viewer (forgive one more Western art allusion), variations on the detail of the Creator’s outstretched hand in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel. Such is the evocative power of much good art.

Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk), “Bella Falcon,” from the series “Strong Unrelenting Spirits,” . Inkjet print, glass beads, rhinestones, shell, thread, 2023

The show also includes three gorgeous portraits of family members of Eau Claire-based artist Tom Jones, and work by Nalikutaar Jacqueline Cleveland, Guadalupe Maravilla, Alan Michelson, and Marianne Nicolson. All 10 artists represent various Native nations and affiliations from North America, including Cold Lake First Nations, Ho-Chunk Nation, Lac Seul First Nation, Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nations, Native Village of Kwinhagak Tribal Government, and Six Nations of the Grand River.

Curator Wendy Red Star is an Apsáalooke artist whose work was included in the Museum’s recent exhibition On Repeat: Serial Photography.

In sum, these photographers launch artful arrows of such varied arches that their multi-circled, multi-colored target stands like a full quiver – cut open wide for inspection and revelation – perhaps like a signifying Native American sculpture itself.

___

This review was originally published in Shepherd Express: https://shepherdexpress.com/culture/visual-art/mam-focuses-on-native-perceptions-in-photography/