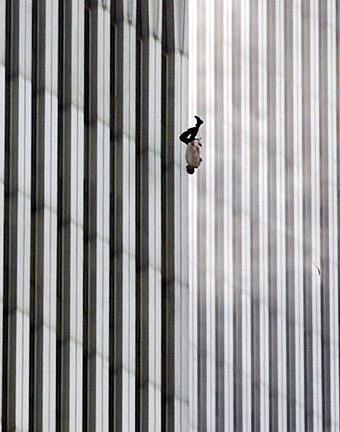

The Falling Man photo by Richard Drew

The Falling Man photo by Richard Drew

Pundits generally agree that the Democrats made more hay with their convention than did the Republicans. I agree — Bill Clinton especially picked off GOP allegations against President Obama like so many ducks in a barrel, and Clinton and Michelle Obama, Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren and a number of other speakers often worked the classic American gospel call-and-response dynamic as if this was a massive Sunday Baptist service.

Actually the best such line came from former presidential candidate John Kerry: “Ask Osama bin Laden if he’s better off today than he was four years ago!” Kerry, of course, is also the Vietnam veteran whose heroic war record was distorted by Republican stooges in the 2004 campaign’s Swift Boat farce, framing him for supposed cowardice.

As for Mitt Romney, the best hard-nosed take on him I’ve read is Matt Taibbai’s in the latest Rolling Stone: “Mitt Romney is one of the greatest and most irresponsible debt creators of all time. In the past few decades, in fact, Romney has piled more debt onto more unsuspecting companies, written more gigantic checks that other people have to cover, than perhaps all but a handful of people on planet Earth.” 1

But for the electorate to understand this opponent, Democrats needed to fire up their base and engage their often fractional culture. Tapping into the call-and-response dynamic was very smart because it may also be a way to allow the coveted undecided voter in — by eliciting a response. At seems to me, undecided voters need to sense that someone speaks to them and values their opinion.

Some of those undecided voters are surely nonreligious. That’s part of the risk of using the call and response, in the context of a nationally televised convention, because it is so associated with religious ritual. I recently had a conversation with an atheist neighbor who has an aversion to any cultural reference with religious association. I mentioned Jesus Christ and the Golden rule as a good fundamental way to live one’s life without any excess trappings of religious dogma. He said “as soon as you say Jesus Christ” you are implicitly approving the religious impulse that feeds into all the extremism we suffer from, the kind that led to 9/11. That’s the stance of New Atheist writer Sam Harris, this man’s new guru.

This seems a needlessly negative stance that disavows all the good that religion has produced through the millennia. Of course, the stance is also very understandable, given the evil, horror, tragedy and trauma that fateful day produced.

The excellent 2006 documentary on 9/11, The Falling Man happened to run on a cable station concurrent to the final night of the Democratic convention, a reminder of the event’s upcoming anniversary. So I switched between the documentary and PBS’s convention coverage. The Falling Man brought home, in harrowing and poetically chilling human terms, the crux of that tragedy. It focuses on the investigation, especially by Esquire writer Tom Junot, into the identity of the man who jumped from an inflamed room in the World Trade Center — in a photograph which has become perhaps the tragedy’s most iconic image.

The photo was taken at 9:41 AM on September 11 by Associated Press photographer Richard Drew. The image also inspired, among other fictional attempts to address this subject, the novels Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safron Foer (also a recent film) and Falling Man by Don DeLillo.

It also brought to mind an anecdote at the Democratic convention about another type of man — a fallen man, of sorts — related by Georgia Rep. John Lewis, himself a minister and a long-time civil rights hero, who walked shoulder-to-shoulder with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He delivered one of the most genuinely moving and perfectly understated moments of the whole political season:

A few years ago, a man from Rock Hill, inspired by President Obama’s election, “came to my office in Washington and said, ‘I am one of the people who beat you. I want to apologize. Will you forgive me?’” I said, ‘I accept your apology.’ He started crying. He gave me a hug. I hugged him back, and we both started crying. This man and I don’t want to go back; we want to move forward.”

I see a connection here to The Falling Man as well. He was, by most accounts, a well-liked and hard-working 43-year-old African-American audio technician named Jonathan Briley. Certainly there’s profound irony in that a man whose race is historically the most reviled in America, rises to a job in the tallest building in America and then plunges to his death on the day of America’s greatest contemporary tragedy. Briley’s sister Gwendolyn saw the picture the day it was published. She knew that Jonathan had asthma, and in the smoke and the heat would have done anything just to breathe. . . .

So Briley became a new archetypal tragic American hero.

His father is coincidentally a preacher who told Junot that he could not address the issue of his son’s death in the photograph because his job is to tell people to go on, in the face of tragedy. That was something he was unable to do at that point.

His sacrificed son can signify the black man who has come so far and his death an acknowledgment of the inhumanity that kept him down for so long.

Here’s where Lewis’ call-and-response line resonated: “Brothers and sisters, do you want to go back? Or do you want to keep America moving forward?”

More broadly, many people who have suffered and died through the last Republican administration signify those who most need just “a fair shot,” as President Obama put it.

The Democrats clearly were willing risk of the call-and-response modality because the inherently inclusive dynamic of the gospel ritual is fundamentally American, and even reclaims some of the religious potency that Republicans and the far right supposedly command.

The falling man who haunts us might even signify the 99% who have all fallen from where they were during the several decades of stagnating wages that led to the proliferation of “the working poor” and subprime mortgage loans and corrupt business and Wall Street practices that led to the recession.

I see the call and response as a reminder of the bottom-line political power of voting. As Obama said repeatedly in his speech, “You did this,” which seemed a deft counter to Republican manipulation of an out-of-context Obama quote, “You didn’t build this.”

(For the record, he was talking in the latter quote about infrastructure, which government pays for most typically. He wasn’t talking about small businesses.)

And as Lewis said, “Your vote is precious, almost sacred. It is the most powerful nonviolent tool we have to create a more perfect union.”

So perhaps we can look back at The Falling Man in terms of a stark beauty begetting spiritual truth. A blog comment by Marnie Watson O’Brien on The Falling Man documentary, put it this way:

“I think the controversial photograph of the falling man is beautiful. He knew he was going to die, and the picture itself is so composed and calm compared to the chaos of that day. It’s quite a stunning and beautiful picture, taken at face value. But if (Briley) could see the picture…I don’t think he would mind terribly that if with his death someone happened to take a picture and it was a beautiful picture. At least one tiny, tiny good thing came out of his death and made people think. We can’t hope for more than that.”2

How tiny that abject figure must’ve felt, as he plummeted from the tallest building in the world. It also seems that in the ensuing decade that “tiny good thing” has grown into a large and potentially powerful good thing.

At the end of Foer’s novel, the book includes a sequence of photographs of another of the twin tower’s falling men. Yet as your thumb slips forward through these pages they become an old-fashioned flip-action device. But Foer arranged it so, in this action, the falling man ascends.

This may seem like facile symbolism, but it’s also a device that would likely appeal to Oskar Schell, the novel’s pacifist nine-year-old protagonist. And it’s another way of looking at an indelible moment. Art, and even political stagecraft, may carry tragic life to new possibility. Otherwise we’re still left with a hole in our heart, as big as Ground Zero. Call and response becomes a collective healing process. Just maybe we can hope for more than what Mamie O’Brien suggests.

2http://topdocumentaryfilms.com/911-falling-man/