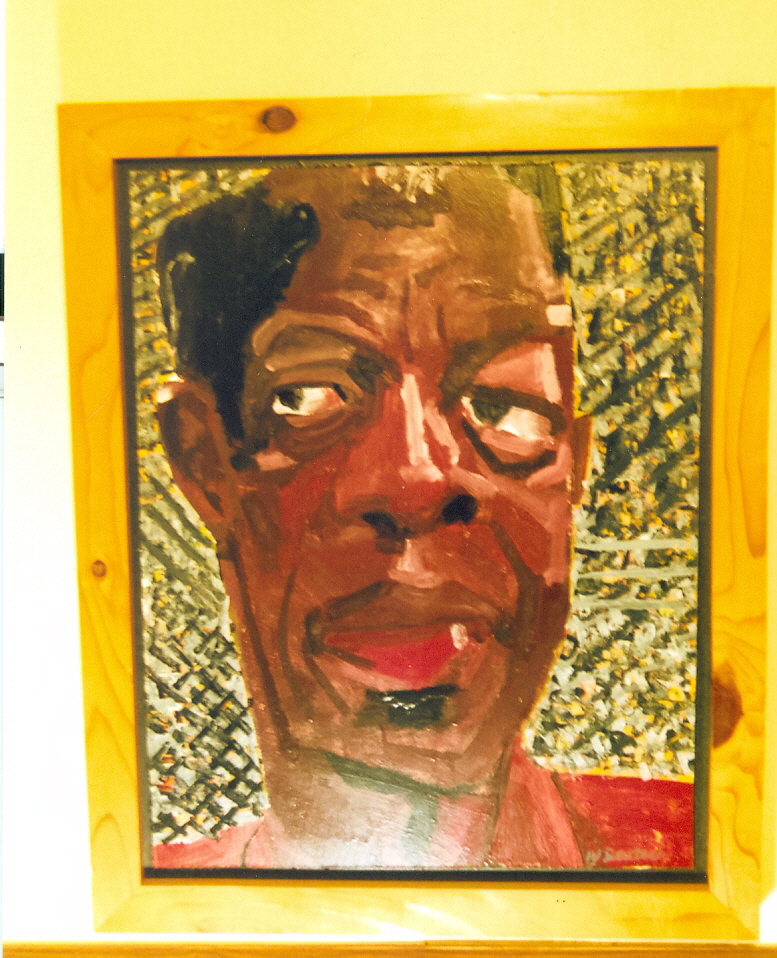

A “hand-painted” reproduction of “Scipio, The Negro,” oil by Paul Cezanne 1864, from chinaoilpaintinggallery.com.

Something stirred in me as it doubtlessly did in Eugene Kane — even more profoundly — when he first saw the reproduction of painting of a sinewy yet vulnerable black man, which his sister Edna gave him 30 years ago.

Kane, my former colleague at The Milwaukee Journal, posted a photo of the painting reproduction on his Facebook page on October 18, wanting to know if any FB friends could help identify the unsigned, unmarked piece’s progeny. I glanced at it distractedly and suggested the influence of Van Gogh and, thinking it may be an American artist, of Thomas Hart Benton. I also flashed on Goya. (Another Kane FB friend, Portia Freckle Eye Cobb suggested an “Art road show” estimate for the piece — which I mention mainly for the pleasure of typing Ms. Cobb’s deliciously colorful name.)

A bit of research by Gene’s friend Sharee Davis identified it as Paul Cézanne’s, Scipio, the Negro from 1865. Cézanne is a personal favorite of mine. How could my memory fail so? In 1977, on a free-lancer’s budget, I pilgrimaged to New York to see his late paintings at the Museum of Modern Art. I should’ve recognized Cezanne’s palette and style immediately, even if he’s best known for his landscapes and still lifes, The Card Players aside.

Cezanne’s card players have been reproduced into endless kitsch and his Scipio risks the same, as he’s now available on a T-shirt, a tie, a clock and a mug. After a certain debatable point, mechanical production dilutes cool into kitsch, partially measured by the relative silliness of the product and the aesthetic compromising of the image. Nevertheless, Gene’s framed, three-decades-old, “hand-painted” reproduction retains a finely-aged cool, and reveals Cézanne’s penetrating ability to probe the virtual DNA of molecular mass, a painterly insight that gave all his work a perpetual inner tension. The painter never let conventional technique obscure this energy.

The force of his shape-shifting abstraction earned him the rightful name of The Father of Modern Art. And in Scipio you see how Cezanne’s painterly grappling with mass touches on the human truth of this African man. Scipio looks almost as solid as a Cezanne mountainside, and yet you sense his palpable human presence in the rough-hewn strokes and highlights. 1 (However the “hand-painted” reproduction above compromises the original and loses aura or authenticity because, to my eye, some brushstrokes are too facile and quick to be Cezanne’s, which typically seem to dig right into the canvas.)

Still you sense that this man, though muscular, carries an unfathomably weighted spirit. It’s the proverbial walk-a-mile-in-this-man’s-shoes image.

His head rests on his left arm, which looks a bit peculiar. But its strangeness is loaded. The limb and the broad white backdrop suggest something emerging from his consciousness or memory — the arm of a lynched slave hanging like “strange fruit from a popular tree,” as Billie Holiday once sang with a searingly desolate empathy. (The racist Ku Klux Klan, coincidentally or not, began in 1865, the same year Cezanne painted Cipio. In retrospect, the white backdrop foreshadows the Klan’s adoption of white robes in their early 20th century revival.)

Kane interprets it slightly differently, with the white form as a Sisyphusian stone. “It’s a strong visual presence for me, a strong black man who seems worn down by his challenges, almost like he’s been pushing that rock up a mountain or something, even though he’s seated,” he says. “Chipping away at the stone, perhaps. Many visitors to my home comment on it; it always gets a reaction.”

Now freelancing, Kane still writes a Sunday Crossroads section column for The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, marked by his sardonic-yet-humane wit and cut-to-the-quick insights, especially regarding issues relating to the African-American experience.

However, without having seen his art work in person, I’m 99.9 percent sure that it is a reproduction of the original Cézanne painting, which is part of the collection of The Sao Paulo Museum of Art, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Unless, that is, Gene’s sister was the real-life counterpart to Renée Russo in the art-heist movie The Thomas Crown Affair.

This is not to extoll the purchase of reproductions over original works of art — especially by affordable local or regional artists. I still abide by Walter Benjamin’s concept of the “aura” of, say, an original painting “which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction,” as he wrote in his classic 1936 essay The Work Of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

Benjamin compares this aura to the experience of nature, “the unique phenomenon of a distance, however close it may be. If, while resting on a summer afternoon, you follow with your eyes a mountain range on the horizon, or a branch which casts its shadow over you, you experience the aura of those mountains, of that branch. This image makes it easy to comprehend social bases with a contemporary decay of the aura.” One social base is “the desire of contemporary masses to bring things ‘closer’ spatially and humanly, which is just is just as ardent as their bent toward overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by accepting its reproduction.” 2

Benjamin clearly challenged the value of mass reproduction. I might offer an example of loss of aura by comparing the two art images hanging over my desk: A print reproduction of Honore Daumier’s Third-Class Carriage from 1864 and an original enamel-on-wood panel portrait Ornette Coleman, of the innovative jazz saxophonist-composer painted around 1997 by Iowa artist Wayne Deutsch.*

An original painting “Ornette Coleman” on left, and a printed reproduction of Daumier’s “Third Class Carriage.” Photo: Kevin Lynch

The enamel painting is such a powerful image that I not-infrequently sense it traversing the distance to my senses – “casting a shadow” over me as I sit at my desk writing. I glance up and the surface of Ornette’s larger-than-life visage glistens in its oily luminescence, pulling me into the depths of his fulsome eyelids and knowing, melancholy eyes, into the creases and asymmetry of his middle-aged face, and the brow marks betraying the burning intelligence of a maverick artist, and the psychic and physical abuse he’s endured over his controversial career.

“Ornette Coleman” by Wayne Duetsch. enamel on wood board ca. 1997 from Metropolitan Art. photo: Kevin Lynch

(Apologies for the poor photo. [by KL] The light on Ornette’s neck really flattens out the image.)

For all his ostensible sophistication, Coleman is, at root, a Texas bluesman which he started out as, though always in his own idiosyncratic way, as exemplified by the double-jointed cowboy swing of his early classic tune “Ramblin’.” Listen here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PN33ULk40a0

This face is a roadmap of a ramblin’ American cultural odyssey.

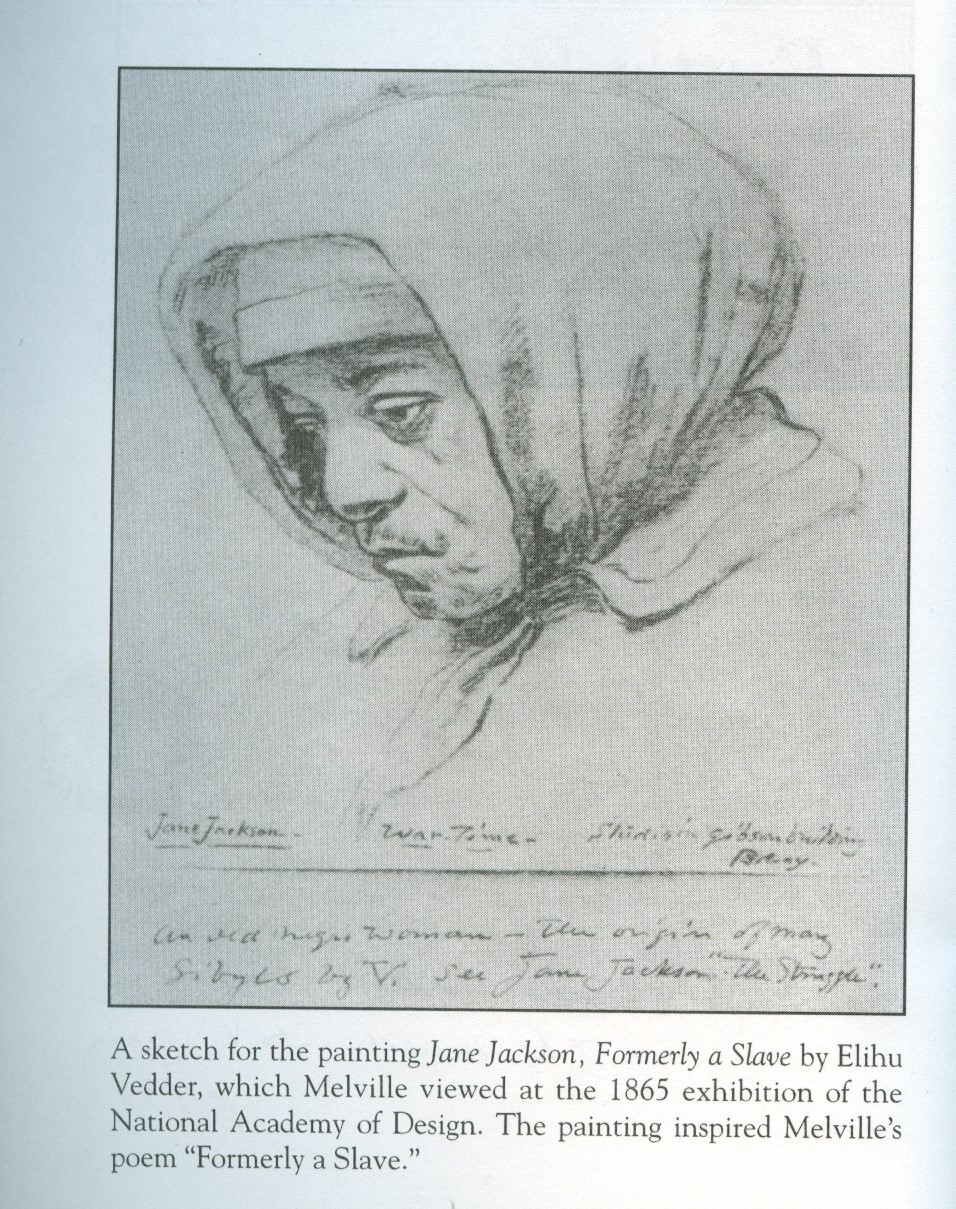

An odyssey, of course, is a great journey far from home and perhaps eventually back — a Homer, a Huck Finn, an Ishmael. This brings me the famous American Ishmael, Herman Melville, and to the extraordinary 1865 portrait by Elihu Vedder, titled Jayne Jackson: Formerly a Slave, which inspired a remarkable Melville poem. By then, Jayne was a “free woman” yet, as she appears to gaze down into the long road that emancipation presents her — she seems to search for a place she might call home, somewhere, in America? In a post-racial Nirvana? Might she also harbor feelings about the “security” of the plantation, as horrible as that experience likely was? She could likely tell about being more than “Twelve Years a Slave,” the title of the new Steve McQueen film based on a true story of a free black man sold back into slavery.

Herman Melville saw Vedder’s sketch for the painting in the spring exhibition of the National Academy in 1865 and was inspired to pen his poem “Formerly a Slave.” The sketch is the frontispiece art in the 2001 Prometheus Books edition of his Civil War poems, Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War. For me and a growing number of readers, this book is one most powerful, insightful and beautiful collections of poetic response to war, and is often compared to Walt Whitman’s Drum-Taps section of Leaves of Grass.

Actually Melville was experiencing the war at somewhat of a distance, not having served in the war as a soldier or as a nurse, as Whitman did. However, he did sneak up to front lines with his Union soldier brother Allan — and accompanied a daring Calvary hunt for the brilliant Confederate guerrilla fighter George Mosby. That resulted in the long narrative poem The Scout Toward Aldie. Throughout Battle Pieces, one senses a balance of distance and immediacy in Melville’s experience which is a literary extension of Benjamin’s idea of the art aura traversing a distance to reach a viewer.

Here’s the poem he wrote about Jayne Jackson’s image:

Formerly a Slave (An idealized portrait, by E. Vedder, in the spring exhibition of the National Academy, 1865)

By Herman Melville

The sufferance of her race is shown,

And retrospect of life,

Which now too late deliverance dawns upon;

Yet is she not at strife.

Her children’s children they shall know

The good withheld from her;

And so her reverie takes prophetic cheer –

In spirit she sees the stir

Far down the depth of thousand years,

And marks the revel shine;

Her dusky face is lit with sober light,

Sibylline, yet benign. 3

Melville’s subtitle “an idealized portrait,” suggests his intellectual distance from Jackson’s “aura,” as do his allusions to the historical implications of her private reverie. And yet, such a poem surely bears a powerfully direct experience of that aura, reaching out to Melville, like Ornette Coleman’s face does to me. Phrases like “prophetic cheer” and the striking “marks the revel shine” detect what we might call the resilient blues spirit within Jackson’s melancholy. 4 And neither Ornette’s nor Jayne Jackson’s eyes look at the viewer so we, especially Caucasians like myself, gaze with a certain voyeuristic wonder, so strong is the artist’s exposure of the subject’s being. 5

If this old woman removed her top and exposed her back, one wonders if it might resemble that of Cézanne’s Scipio, who seems to carry a slave’s experience in his body.

And yet, I also return to the Daumier reproduction which, though the lacking the “Ornette” painting’s aura, is beautiful and moving. Daumier’s unsentimental visual storytelling from 1864 highlights the central figure, an elderly woman in the third-class train seating who seems like a kindred spirit to Jayne Jackson. In fact, Vedder’s sketch and painting of Jackson were done a year after the Daumier. So Vedder, a cosmopolitan American who had studied in Paris, had possibly seen Daumier’s image not long before portraying Jackson, the “Sybilline” — a female prophet. They are both masterfully attuned images of humble yet potentially transcendent women (notice the elderly passenger’s private smile and almost serene expression) enduring social systems stacked against them. 6

Today Walter Benjamin may be subject to charges of elitism; his essay bemoans how movies are an experience of a “distracted public” as opposed to one that concentrates on a single painting and its aura. The democratization of art allows multitudes edification, entertainment, inspiration and aesthetic pleasure from living with a great art work’s image, though bereft of its “aura.” Yet cultural democratization comes at a price, which fosters illusion. Reproductions have improved, as has the quality of photography and film, both advanced commercial art forms in their own rite, of course. Sure, HD TV offers a new intensity of apparent clarity. Yet digital pixilation filters out any residual sense of the artwork’s inherent presence.

Plus, Benjamin, a German-Jew writing in 1936, ends his essay by brilliantly forecasting how Fascism would latch onto mass reproduction to disseminate unprecedented amounts of racist, Aryan-suprematist propaganda, which helped instilled the mass mentality that led to World War II and The Holocaust. Today, we have accumulating evidence of the pervasive dangers of Internet media to privacy and civil liberties, even as The Web allows new sorts of freedoms, illusions thereof, and traps.

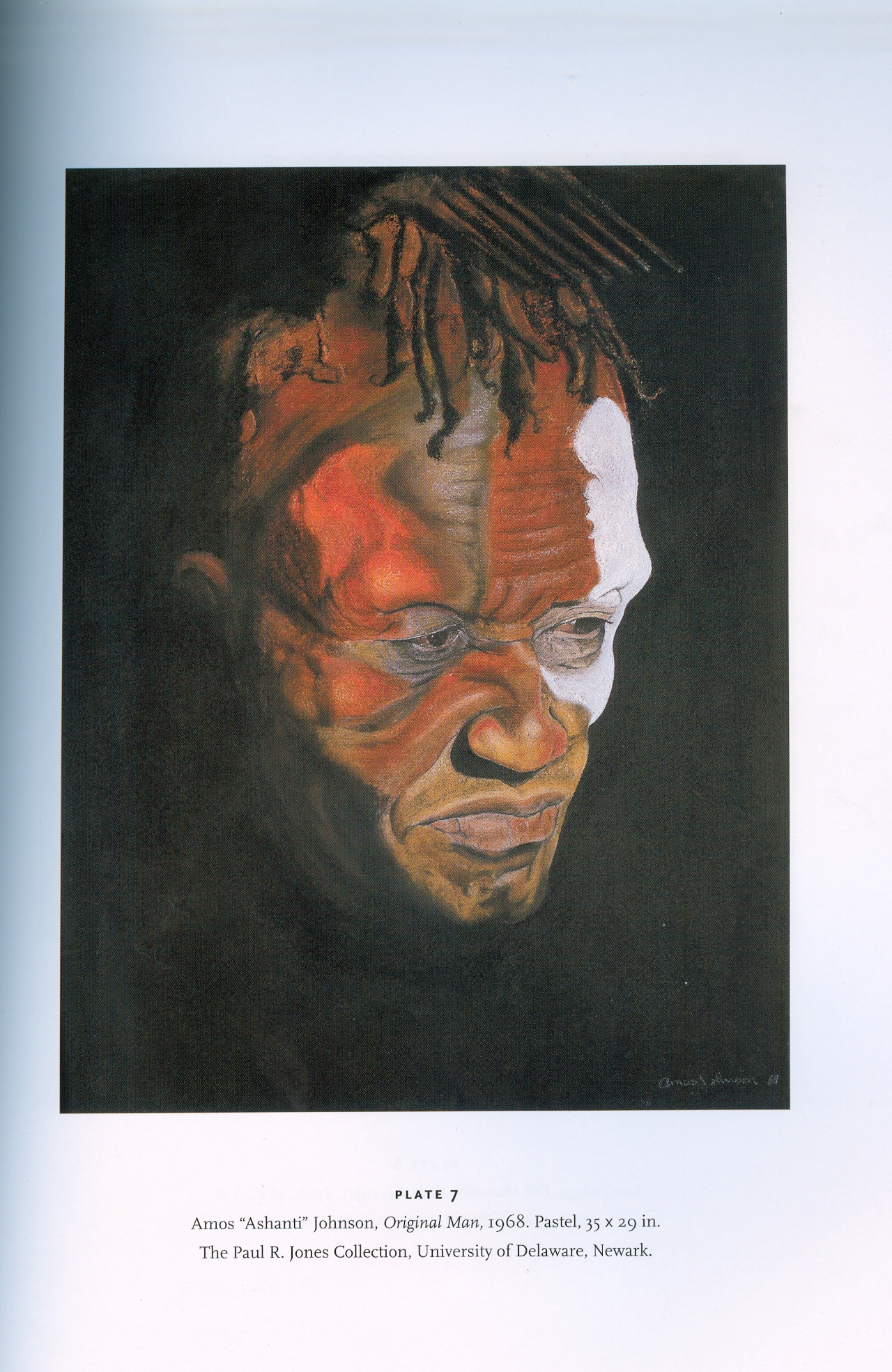

If only the Nazis (or the KKK or any racist groups) comprehended the implications of a painting like Amos “Ashante” Johnson’s Original Man, a 1968 pastel. It alludes to Africa as the historical motherlode of humanity. The deeply symbolic portrait from the great Paul R. Jones Collection of African-American Art, also addresses “notions of the evolution of man, and alludes to the fundamental relatedness of all people,” writes essayist Amalia Amaki. “With the background blacked out, the multiethnic head appears to float out of infinity.” 7

Ultimately, a reproduction should inspire us to venture to see the original artwork, to buy original art, to expand and intensify our experience of artistic truth and beauty. Let art’s aura breathe. Feed it like your senses, embrace it like your lifeblood. I think most art of value is a creative byproduct of our “better angels,” even if it is blasphemous, as Melville’s Moby-Dick sometimes is. As Melville wrote to his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, upon finishing his masterpiece: “I have written a wicked book, and feel spotless as the lamb.”

And, after years of toiling in the trenches of daily journalism, Eugene Kane deserves — perhaps with sister Edna — a trip to that museum in Sao Paulo, Brazil. What a way to beat another Wisconsin winter.

___________________

* “Ornette Coleman” by Wayne Deutsch was a gift from my ex-wife, Beth Bartoszek, purchased at Jeb Prazak’s Metropolitan Art in Dodgeville WI, which is no longer open.

1. Cezanne may have titled painting for his subject’s actual name, or he may have chosen to give the man historic resonance. Scipio Africanus was the name of an African general and statesman in the Roman Empire, which clearly lends symbolic power to his identity, burdened as he may appear.

2. Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, Schocken Books, 1969, 222-223

3. The excellent Prometheus edition of Melville’s Battle Pieces corrects some egregious omissions and printing mistakes in the University of Massachusetts Press edition 1972. Prometheus also includes a forward by Civil War historian James McPherson, an invaluable interpretive essay by the great poetry critic and scholar Helen Vendler, as well as essays by Rosanna Warren, Richard Cox, and Paul Dowling.

4. The cultural historian and critic Albert Murray and novelist-essayist Ralph Ellison (The Invisible Man) are two writers who explicated the concept of “the blues spirit” as an aspect of the African-American experience and perhaps character long predating the formulation of the blues as a musical genre in the 20th century.

5. In Vedder’s finished painting of Jayne Jackson she seems to exist in a murky cloud of existential uncertainty. One wonders if Melville’s poem would’ve been as hopeful had he seen this painting, part of the Frick collection:http://images.frick.org/PORTAL/IMAGEINFO.php?file=/Volumes/digitallab_xinet_5/NEH_grant/acetate/POST/folder/50130_POST.tif

6. The African-Americans: Many Rivers to Cross, the current PBS series on Tuesday nights, hosted by cultural historian and critic Henry Louis Gates Jr., offers a great opportunity to understand how our social systems have historically dealt with the African-American. The series also seems to be employing many storytelling visual art images. One wonders what Benjamin might have made of such ambitious and high-minded cultural democratization. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/

7. A Century of African American Art: The Paul R Jones Collection, ed. Amalia K. Amaki, The University Museum, University of Delaware and Rutgers University Press, 2006, 9

Kevin,

I found this blog so enlightening, knowledgeable and interesting.

Thank you so much for all your expertise and ‘stimulating to consider’ points

to ponder.

One never knows so much as to not be able to learn something new and a “bad”

day is one where you don’t.

Will definitely pass along to my students.

Please continue, Jeb

Thanks and much appreciated Jeb,

I’m here to serve just such purposes as your mention. I hope this site helps your students and you. Hope you get a blog up and running as well. Stay in touch.

Kevin