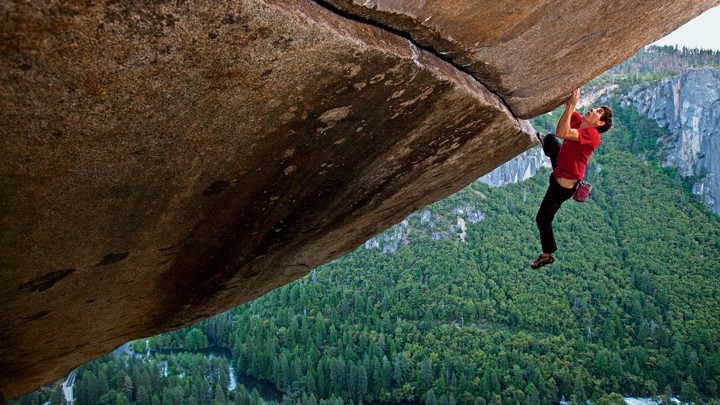

Alex Honnold attempts to climb the great face of Yosemite’s El Capitan without any equipment (or sanity?) in “Free Solo,” a new National Geographic Documentary. Courtesy The Atlantic Magazine.

Free Solo, a National Geographic Documentary film by Elizabeth Chi Vasarhelyi & Jimmy Chin. Held over until Monday Dec. 10 at the Oriental Theater, Milwaukee,

Also showing at Silver Cinemas at Market Square Theaters, Madison, held over through Tuesday, Dec. 11.

Check theaters for possible run extensions and other info.

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity.”

― John Muir, Our National Parks

Goddamn. You groan inside. Other emotional responses may surge up, while watching Alex Honnold climb alone and unroped – or free, in climbing parlance – up a long, vertical crack of the astonishingly, daunting face of El Capitan Mountain in Yosemite National Park, in 2017. It’s considered the toughest mountain face in the world – 3,000 feet of a monstrous granite elephant’s twitchy hide, enduring a single human ant.

You follow him up the towering crack, the zig-zag path of rock seemingly formed by a face-splitting lightning bolt, or maybe several lifetimes of such blasts.

This sequence of pitches* requires hand jams and hand hooks against the vertical crack. When the crack opens wide enough, Honnold must shimmy his tensile body slowly up the chimney. Tough enough, but then, seemingly exhausted, he must perform a series of crazy moves of balletic delicacy and sheer stamina. No ropes. No pitons. No circus nets. Nothin’ but the chalk on his hands and fingers, to keep them dry. He’s at maybe 2,000 feet now, clinging to a vertical world, just barely.

Are you still breathing?

This astonishing, often-gorgeous and brilliant film records Honnold’s five-year odyssey to climb the face “free solo.” He had bailed out in a previous attempt, while recovering, but not completely, from a severely sprained ankle. Earlier, on a practice climb, his brand new girlfriend had absently let the rope run out of the belay lock she was controlling. That fall had tested his relationship skills, far less assured than with a rock face. Honnold threatens to break up with her, thinking she’s an unreliable climbing partner.

However, he’d made that first free attempt in pre-dawn darkness, calculating he’d need all of daylight to reach the top. There will be no bivouacs on this climb. Yet he freezes up on one of the first difficult points. I suspect the shroud of darkness, pierced only by his headlamp, penetrates what he calls his “armor,” which he also likens to the attitude of a samurai warrior, who gamely faces, even embraces, death. Because it’s what is necessary.

Alex Honnold works his way up a long vertical crack on El Capitan. Courtesy Amherst Cinema

It’s easy to adopt a fraternal or paternal sense of protectiveness toward this boyish man, with black, tousled hair, and large dark, searching eyes and a handsome yet almost gaunt face and body. So he’s “Alex” to me now. His chiseled body gives you faith in him physically, yet he’s lean and not overly muscled like many contemporary athletes. It’s actually the perfect body for such extraordinary athleticism, as too much muscle might constrain the needed range of motion in his limbs.

I have some sense of this, and of Alex’s virtuosity and courage, being a former mountaineer (more on that below).

Outside magazine calls Free Solo “the best climbing movie ever made.” And there are quite a few vertically-fixated movies if you follow such things. Free Solo comes from a married couple, filmmaker Elizabeh Chi Vasarhelyi, and cameraman Jimmy Chin. They also created Meru – a powerful 2015 documentary of windswept urgency and dread – detailing a climb Chin attempted with two other men of Mount Meru, in the Himalayas. Chin, like all of his film crew, are trained climbers. He’d explained in Meru that he only works with people that he knows personally in his mountain climbing documentaries.

Camera crew documenting Honnold during the making of the film “Free Solo,” on El Capital in Yosemite National Park. Courtesy IndieWire.com

Chin knows Alex Honnold, already an acclaimed free solo climber, perhaps as well as anyone can. The closer we get to Alex, the further we get from him, it’s that “armor” climbers of this sort speak of – a psychological shield against fear, in a given moment.

Yet this shields his peripheral vision towards empathy or other interpersonal skills. We learn that Alex’s father was likable but remote, a man always needing to travel, just as Alex always needs to climb, or prepare for another.

“He was a teddy bear to me,” Alex recalls with measured affection for a father who supported his youthful climbing zeal. He admits that no one in his family ever used “the L word” (“I love you”) except in French, (je t’aime), as his mother is a teacher of French. That once- removed quality of expression may allow his mother, who’s briefly interviewed, carte blanche emotions in allowing her son full freedom. When he develops a relationship with a young woman, Sanni McCandless, it’s rocky right from the moment she allows him to fall.

But he’s in the middle of training and practice for the free solo on El Capitan, an unprecedented feat. But Sanni is a strong, big-hearted and brave woman. He sticks with her and their relationship blossoms like a couple of wildflowers emerging from a high mountain wall crack. But her roots touch the earth. So her own trail in his footsteps is the film’s subtext and it’s emotional crux.

When he finally goes for it, for broke, in very early daylight, her tears well up in Alex’s live-in van, wondering if she’ll see him again. From this moment, the intensity and drama ratchet up, more than most conventional thrillers I’ve ever seen. It’s hold-your-breath reality-show time. Ms. McCandless used all her persuasive skills and wiles, and perhaps burgeoning love, to quietly will Alex up the great face, and back from the fatal brink he’s almost sanguine about.

The massive, intimidating 3,000-foot face of El Capitan in Yosemite. Wikipedia

Among this obsessive climber’s most revealing and thought-provoking comments is a reference to “the bottomless pit of your self-loathing.” It seems to come out of the blue in his narrative voice-over, casting a certain pathos over this tale, rich with mythical and tragic overtones. Several great climbers that he has personally known die while climbing elsewhere during the five years he prepares for his solo attempt at El Capitan.

His emotional response feels like little more than the famous “so it goes” from Kurt Vonnegut’s comic tragic Slaughterhouse Five.

Ass accomplished and seemingly prepared Alex is, there’s no denying free soloing’s essential recklessness. “People who know a little bit about climbing are like, ‘Oh, he’s totally safe,’” Tommy Caldwell, one of Honnold’s best friends, says in the film. “People who know exactly what he’s doing are freaked out.”

On the morning he finally attempts it again, he eats his standard breakfast of oats, flax, chia seeds, and blueberries. He feels great, maybe “in a zone,” the temporary quality of an athlete who can seemingly do no wrong. You see it in the heightened, yet easy, rhythms of his moves; there’s almost a swagger in his swing, ape-like, from one precarious handhold to another.

For sure, this attempt is one of the greatest athletic feats you’ll ever see on film, even if Alex may fall to his death – right before the camera crew. The whole emotional, psychological and circumstantial reality of this attempt gives the film its gut-churning tension. And perhaps even a moral conundrum, if we watch him fall, and if the cameras do as well.

Alex Honnold, from left, and Sanni McCandless, subjects of the documentary film “Free Solo,” pose with co-directors Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin at the InterContinental Hotel during the Toronto International Film Festival in Toronto, Sept. 10, 2018.Voanews.com

****

I have one comparatively modest but dangerous experience with free solo climbing which helped transfix me in this film. Through much of my 20s, until age 30, I climbed a number of times in The Tetons, but one summer I was unable to get to Wyoming. In late August, when I’d normally climb, I drove up to Door County, on a camping trip with a friend, Frank Stemper. Somehow, the hulking former high school football guard came down with the flu. Itching to get out and do something, I left him in our tent, with Sam, his lovably oafish shepherd-dog mutt.

I’d noticed intriguing cliffs along the highway through Peninsula State Park. By the time I walked along the highway to some alluring rock faces, the afternoon sun had faded badly.

Nevertheless, I found one route snaking up to the top of the cliff, what would be three or four moderate pitches. I began climbing and at some point noticed looseness amid the wall rocks, which I later learned are primarily limestone. I reached the top without terrible difficulty and probably started chuckling to myself, a tad too self-satisfied, as if I was my old house cat Fred, settled and regally surveying, as cats do, his home below from the highest possible perch in the house.

Now, a small detail most smug climbing cats negotiate with little consternation: I needed to get back down, to the highway. So I tried a few paths down but they mocked me with the yawning space over the toothy, jagged edges of a drop-off, not far below the top. Now I was a free solo “ant” inside and looking out, after foolishly crawling into the stone elephant’s mouth. I searched further along the cliff until I found a spot that looked manageable.

I gingerly began a downward climb (the well-established El Capitan route in Alex’s memorized climb includes a significant downward detour). What was I thinking then? Something like, “Do you know what you’re doing?” At about a third of the way down, I encountered an overhang that I knew I couldn’t get past. Right then, my upper handhold gave way, and a rock fell, hitting my face. Off flew my glasses, tumbling far down into the wooded space below. 2

I’m quite near-sighted, and now sweat and fear commingled with the blood the rock had drawn from my forehead. My “armor” was cracking. I mumbled something to Jesus Christ. Then a “blessing”: nearsightedness allows you to see things close to you, while points beyond blur into a haze. I could see fairly well at arm’s length distance, and just about to my feet.

I realized the only way I could proceed downward would be around a rocky corner where I could see a small ledge. I mustered my courage, traversed to the corner and managed to swing one foot over thin air, around the corner, to a toe hold; then the second foot came around, oh-so-delicately, to the toehold nub. In the traverse around the corner, my body was 98-per-cent out in space, high over thin air. The next toe step led me to the small ledge. I settled on the small horizontal strip, my body collapsing a bit, and grabbed hold of small green branch in a crack beside it. Now I wonder, did such a wildflower branch save Alex, at some point.

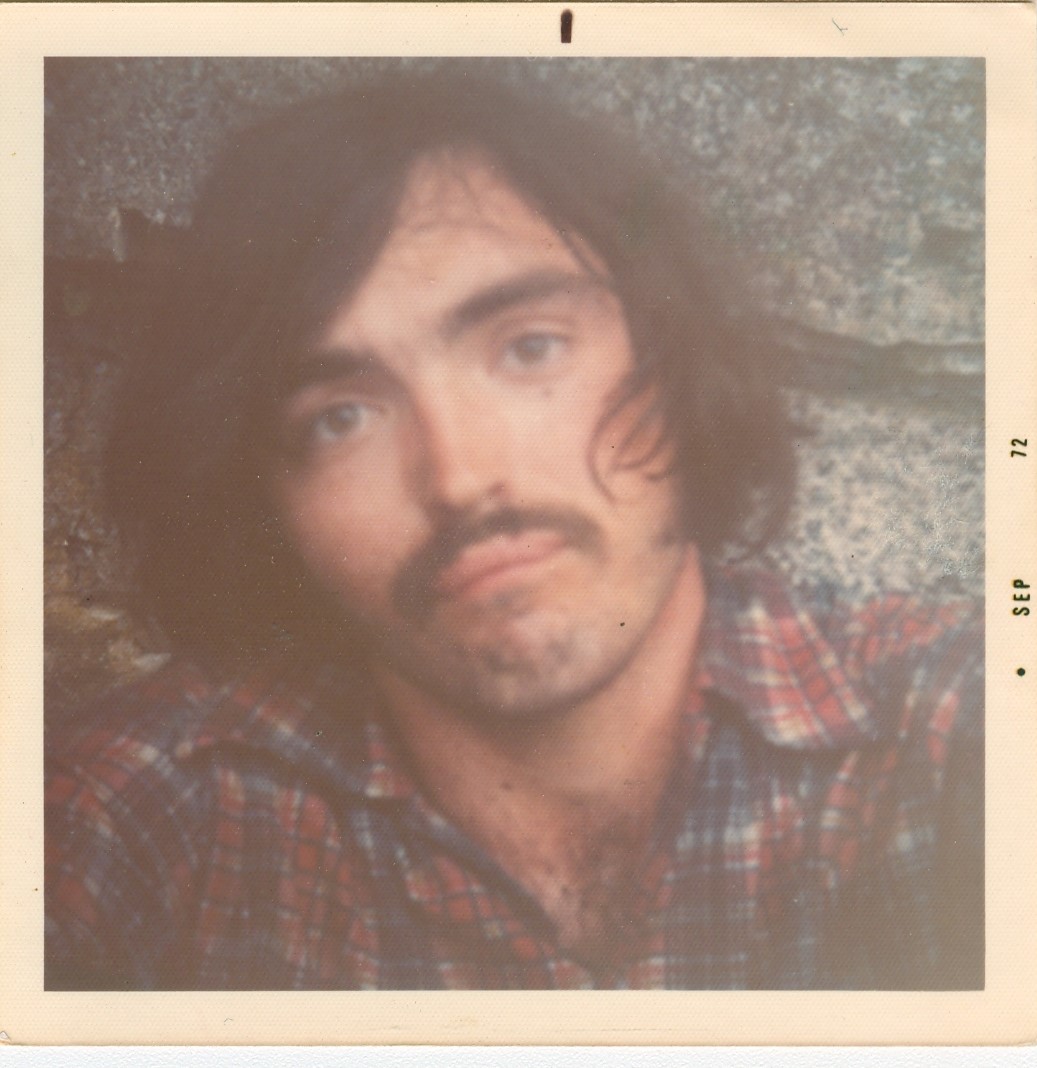

For posterity, I took a forlorn selfie, circa 1972, with a camera I’d brought along. A few moments of glazed admiration of the view, through the golden-brown leaves, with the waters of Green Bay glistening slightly in the setting sun. My wits, strength, and will renewed slightly. I finally worked my way down to the bottom of the loose-rocked, treacherous cliff.

Posterity selfie taken by blogger Kevernacular amid his free solo escapade on a cliff in Door County, ca. August, 1972. Photo by Kevin Lynch

I found my glasses in the brush and, nearby, another pair of eyeglasses, the frame cracked, and lenses long gone. The story of those glass frames remains a kind of mystery, just as does the forces that drive people to climb dangerous walls and peaks.

I’m convinced a big part of the force is spiritual. There is a long, transcendent moment late in Free Solo, when Alex rises through one of the toughest final pitches. Chin and his daredevil film group capture — behind the tiny, ascending figure — a backdrop of El Capitan’s broad, magnificent face, now ablaze in sunset, and glorious shades of mottled bronze, copper and gold. This is mighty granite’s mossy, chameleon powers. Yosemite’s waterfall cascades beyond. Magnificence amid high drama, with overtones of the human sublime.

I hardly suggest anyone begin climbing El Capitan in search of gold, only if you truly need the kind that ends up glowing in your soul.

As a survivor of a foolhardy-youth free solo climb, and bearing truly grand memories climbing in the Tetons, I retain embers of that inner fire.

______________

- A “pitch” is each sequence of a roped climb, from one belayed (secured) spot (station) to the next. In free climbing, you have, in theory, moments to rest in these places, originally established on El Capitan with pitons (large spikes with rope loop-holes) and carabiners. On such a dangerous climb, even the most secure “belay stations” are extremely exposed (that is, very susceptible to a climber falling off).

2. My Door County climb cued up an extraordinary experience later that year. John Boorman’s 1972 film Deliverance came out, based on James Dickey’s extraordinary survival novel. Frank and I went to see it. Four suburban friends take a canoe trip on the Chattooga River, deep in Georgia’s backwoods, eventually reaching the Tallula Gorge.My experience flashed completely back to me during Ed’s desperate climb up the gorge cliff above the river rapids, to try to kill, with bow and arrow, a rural-dwelling rifle man who has killed one of his canoeing friends. Halfway up the cliff, Ed (Jon Voight) drops his wallet after peeking at his family’s photograph. He curses mightily and, right then, I felt my glasses, and some of my hope, falling off my face, into the Door County void. The long Deliverance scene was an uncanny experience of “been there…” Now, though I no longer hold grand climbing designs, (with bilateral arm neuropathy and a partially lame left hand), Free Solo has raised my bar of dramatic empathy to previously unimagined heights.