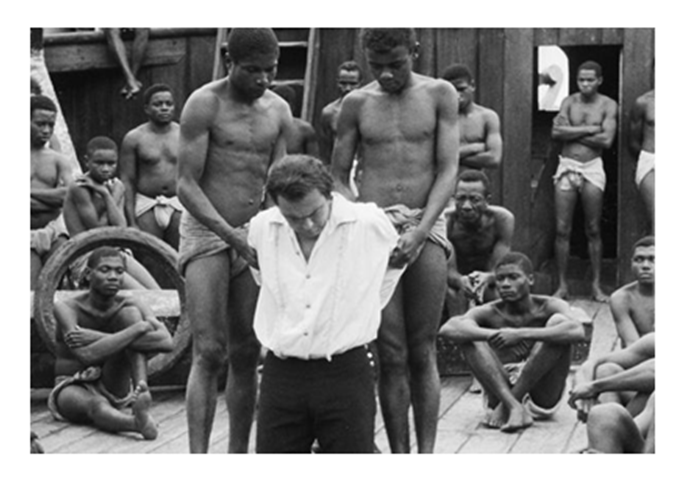

This is a scene from Serge Roullet’s 1967 film adaptation of “Benito Cereno,” Melville’s novella about an actual slave rebellion aboard a Spanish ship.

Toni Morrison’s essay “Melville and the Language of Denial” in the most recent issue of The Nation shows us how Herman Melville, time and again, instinctively positioned himself on the fault lines of American society, politics and culture. In Benito Cereno, (which she discusses), Moby-Dick, The Confidence Man, “Bartleby the Scrivener” and other works, Melville conveyed an Ishmael-like sense of being an outsider/outcast even though the author was born into upper middle-class with a patriotically American heritage of Revolutionary War hero ancestors. Yet, his father died a ruined man when Melville was young, leaving his family in poverty.

Thus, Melville often worked themes about the agitations between the powerful and the powerless. Benito Cereno is so shockingly striking in that Melville slyly exposed the potential within the seemingly powerless, that of Babo’s radically covert rebellion, which Morrison, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist, aptly characterizes as a rational, if enraged, human unwillingness “to be kidnapped for.”

Melville based his story on a true event that occurred in 1799. 1 What unfolds is a strange tale of stifled horror that might be reminiscent of Poe, while casting a wider net of anguish across the political spectrum than the horror-and-detective tale master seemed capable of. The captains signify two men dwelling in intermingling mindsets fed by types of language of racial denial. Spanish Don Benito Cereno praises and condescends to his seemingly domicile black servant, Babo. He tries to hide from his American guest, Capt. Amaso Delano, the fact that the slaves have taken over his ship. So he builds a smokescreen over the reversing power dynamics afoot, so that the unwitting Delano can do little more than a proceed in passive manner of empowered compliance and complicity.

Meanwhile, Babo’s slithering unctuousness intensifies the scenario’s almost absurdist manner, presaging a Hitchcockian black humor, especially in a harrowing scene where the servant — who’s the revolt ringleader — shaves his “master’s” beard. The story ends with a horrifying image that signifies a form of ultimate retribution. Melville clearly suggests that the slave’s extreme response may be the only way to cut the problem off at its roots. Of course, we know it was never as simple as that, as Melville surely knew, and yet the simmering intensity of his tale exhorts us to stay the course to a greater truth and candor in our race relations, and to possible ways of healing.

Here’s the cover to a downloadable e-book version of the novella “Benito Cereno” courtesy of readfwd.com

Further proof of the novella’s seemingly perpetual provocative edge is how Morrison can write up a few paragraphs of response to it in January of 2014 and provoke such a wide ranging flurry of pointed — if sometimes ignorantly informed — commentary on the festering fissures in America’s complex racial divides.

It is interesting that one of the most ostensibly shrewd online comments to her essay comes from chris8lee, someone who exposes himself for apparently not even knowing who the author is and the context of her comments, as perhaps our greatest contemporary literary chronicler of the slave experience (best known for her Pulitzer-winning novel Beloved.) Yet that commentator totters along the edge of the racial chasm with a characteristically white sense of entitlement and self-satisfaction that “washes his hands” because he postures himself as above the fray.

The Nation reader chris8lee also oversimplifies a Higher Power’s “moral grip” on fate, saying that life is always “just.” Tell that to thousands of slaves who suffered and died under the South’s chattel slave system, indeed, millions of slaves who suffered worldwide in Arabian slave systems, as other comments point out.

The dialogue reveals the need for ongoing struggle for true racial justice which will always remain a struggle to some degree, as Frederick Douglass made clear, if we are to progress beyond the paradoxical social quagmire we were born in and maintain to the present.

Here’s the link to Morrison’s essay:http://www.thenation.com/article/177824/melville-and-language-denial

Writer Greg Grandin, whose query about Benito Cereno to Morrison prompted her response, also offers in the same January 27th issue of The Nation an excellent essay “Reading Melville in post 9/11 America” which even addresses issues such as Islamophobia.

________________

1 Melville imaginatively based Benito Cereno on Chapter 18 of Capt. Amaso Delano’s A Narrative of Voyages and Travels, from either the 1817 or 1818 edition.

Thanks to Ed Valent for pointing out the Morrison essay to me.