Milwaukee blues musician Steve Cohen (left) holds a letter written by his grandfather, an American soldier, to document his witnessing of a Nazi death camp at Buchenwald in 1945. Cohen found the letter in the possessions of his uncle Neil Cohen (right). Courtesy Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

Milwaukee blues musician Steve Cohen (left) holds a letter written by his grandfather, an American soldier, to document his witnessing of a Nazi death camp at Buchenwald in 1945. Cohen found the letter in the possessions of his uncle Neil Cohen (right). Courtesy Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

This is The Blues.

This is the blues in the most profound sense of the art form. Its implicit state of mind and spirit is born of the black experience, the black genocide that was slavery. Yet, by extension, this sensibility is shared by all of humanity that is oppressed by forces from within or without. That is the music’s universality.

This is the blues, as expressed in a 12-page handwritten letter that Al Cohen, a Jewish-American Army soldier wrote in 1945 to his mother back home, after he entered and witnessed the carnage and genocide of the Holocaust in the Nazi concentration camp at Buchenwald.

This is the blues that Steve Cohen understands in the core of his being, partly because that soldier was his uncle. There’s a deep strain of Jewish klezmer music’s mournful penetrating microtonalities in Cohen’s understanding of the music. That lineage and history contributes to what has made him among the greatest blues musicians that Milwaukee has produced since the blues revival of the ’60s.

Some readers of this blog, oriented to American music vernaculars, would specifically know Steve as the central figure of the longtime Chicago-style blues band Leroy Airmaster. But he’s also a blues scholar and, in recent years, has deeply delved into and performed the roots of the blues, that is, country blues from Charley Patton, Son House and Robert Johnson forward, especially as he has become a more accomplished singer and guitarist, along with his virtuoso harmonica playing.

Further, many blog readers and online media consumers don’t read daily newspapers much these days. So you may have missed the feature in a recent Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel about Cohen’s uncle. Steve’s familiar face in a photo (above) made sure I saw the story and it’s a good one.

But the core of it, Al Cohen’s remarkable and disturbing historical letter, was glossed in Stingl’s relatively brief column. Steve Cohen had recently discovered the letter among his uncle Neil Cohen’s papers. When his uncle Al Cohen saw the horrors of Buchenwald he wrote the letter to his mother and insisted that she share it as much as possible, so that people would understand the tragic inhumanity of the Nazi Holocaust. The stuff of “never again.”

American soldier Al Cohen, who wrote the letter describing the Nazi death camp in Buchenwald. Courtesy the Cohen family

Apparently Al’s mother was reticent about sharing the letter, which includes graphic, troubling details, and it never saw much readership beyond her.

It’s fortuitous that it has come to light and can be shared now, because anti-Semitism and neo-Naziism, and racially-motivated hate crimes and hate speech, seem to be on the rise, as well as the strange phenomenon of Holocaust denial.

This important letter is a primary historical source, as researchers say, something that provides greater understanding of larger truths that we can build from, for a better society.

That is why Culture Currents believes it is important to share it as well online. After Stingl’s the article, The Journal-Sentinel received a strong clamor from people who wanted the letter published in full. The newspaper belatedly transcribed and posted a copy of the letter online.

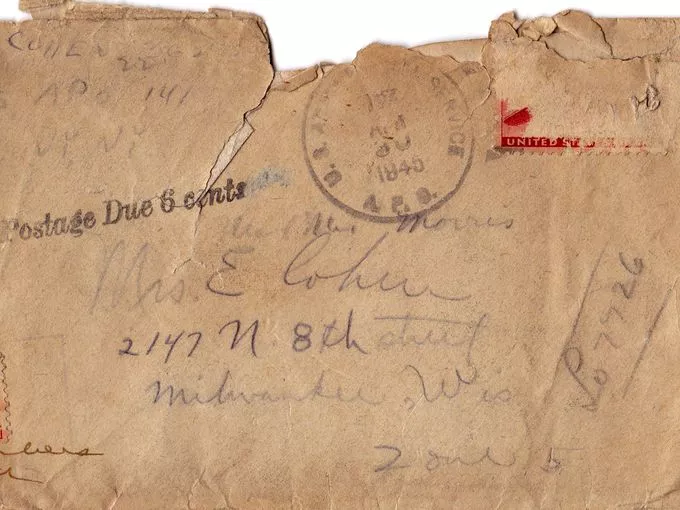

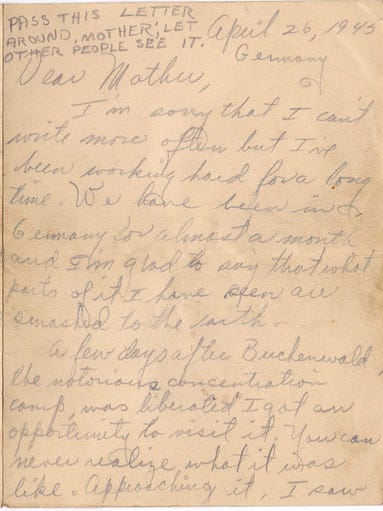

But here it is for Culture Currents readers, courtesy of the Journal-Sentinel and Steve Cohen. Here’s page one of Al Cohen actual letter, then the full transcription:

The first page of Al Cohen’s 1945 letter to his mother.

Here is the complete transcription of Cohen’s letter describing the Nazis’ Buchenwald death camp:

April 26, 1945

PLEASE PASS THIS LETTER AROUND, MOTHER, LET OTHER PEOPLE SEE IT.

Dear Mother,

I am sorry that I can’t write more often but I’ve been working for a long

time. We have been in Germany for almost a month and I’m glad to say that

what parts of it I have seen are smashed to the earth.

A few days after Buchenwald, the notorious concentration camp, was

liberated, I got an opportunity to visit it. You can never realize what it

was like. Approaching it, I saw people dressed in striped pajamas – like

clothing walking around. They were thin as skeletons, weak and quiet, just

walking around aimlessly. The place was surrounded by barbed wire fences

and overlooked by towers where guards used to stand. The enclosure was

very large and for the main part filled with wooden barracks. Across the

street were S.S. barracks and factories. As I entered, my attention was

attracted to a pillory (?) in which inmates were locked and beaten by SS

men with clubs and a tin whip. There were other things that Nazis had

constructed to torture people in the country too.

The next place I visited was the oven room. Entering the basement, I saw

the room where as many as 80 people at a time were hung by their hands

from pegs high on the wall and beaten to death with big wooden clubs. When

they were dead or almost so, they were taken down and loaded on an

elevator, then hoisted up to the ground floor where they were shoved into

ovens and cremated – dead or alive. There were still partially burned

bodies in the ovens.

Walking outside, my attention was drawn to a huge wagon in an inner square, filled with corpses. They were skinny shrunken bodies with big staring eyes and open mouths. It was so horrible that I was not bothered by it at all – it seemed too unreal. Believe me though, I

have seen with my own eyes what sights I describe. Some of the boys took

pictures of this and I’ll send some home at my first chance.

Every once in a while, some of the inmates would bring in a pushcart full

of bodies from the woods where the S.S. troops had taken them and shot

them. These corpses were dumped on a pile with others which were later

taken away to be buried. They were heaped together like a pile of leaves.

The hospital was a dirty grimy building and it was the smelliest place in

the whole camp. This was probably caused by the dirty bed clothes and the

dead and dying people. It was hard to tell the difference; they both had

purple skin. The main cause of death was malnutrition. There were barracks

after barracks filled with people who were slowly dying from that cause,

whom it was impossible to serve. The inmates were beaten down, broken-spirited people. Til the time when the Nazis had to leave there were 51,000 killed in the camp and there

was a high monument with that number on it in the center of the courtyard,

which had been placed there by the Nazis to commemorate their murderous

achievement.

I spoke to some Polish boys of a group of boys my age. They were placed in

a concentration camp at the age of seventeen and were there for five

years. They told me that the only thing that concerned the Nazis was how

to kill the people fast enough. One of the methods they used at first was

to inject chlorine or a strong acid either into the heart or veins with a

large hypodermic. This killed them instantly but it was not efficient for

large numbers of people so new methods were evolved. They were herded into

a large barracks, 800 at a time, and all the doors and windows sealed off.

SS men stood guard – a week later all the people in the barracks were

dead. The Kommandant’s wife was an ugly woman but it meant 25 lashes for

any men who looked at her. Her hobby was making lamps and knick-knacks of

parts of humans.

The food at the camp was not fit for human beings. It was dirty looking

soup and coarse-grained bread. In one barracks of living-dead men there

was a collection of rotten potato peelings which the prisoners were saving

to supplement their meal. I had brought them K rations and cigarettes from

stuff I had accumulated and they went for those things as if they were the

most wonderful things in the world to eat. The joy of seeing that I had

done some little thing to help them was worth all the discomforts and

disappointments I have found in the Army.

One old man walked up to me and stood there staring at me with a

holy-looking smile of gratitude on his face. He quietly thanked me for the

things they had gotten. I told him “I knew how it was – my name is Cohen.”

He said again, quietly, “When you came in the door I could tell that.” I

never felt prouder.

The Polish boys told me that often the people in the camp were starved

badly. One day there was a wagon load of a hundred corpses standing in the

yard waiting to be taken to the crematorium. When the driver came out to

take his wagon away, there were only 80 bodies remaining in the cart and

there were prisoners standing around eating arms, shanks and other human

parts. This scene was witnessed by these Polish boys – it is not just some

thing they overheard being rumored. For all I know, they may have

participated themselves.

The Nazis used to fill little pails with ashes from the furnaces and sold

them to the relatives of the murdered. Usually they were not even the

ashes of the person they were said to be.

We are deep into Germany now and capturing prisoners quite often. Just

this afternoon at lunch there were captured in front of our mess hall.

Things are more difficult now that there is nothing to worry about. I’m

scared and a scared man is always careful.

Thanks very much for the package.

This letter is long so I’ll close it with lots of love,

Al (Cohen)

__________________

p.s. here’s a link to Al Cohen’s full actual letter, scanned to the Milwaukee Journal Online. https://www.jsonline.