“Gil had the distinct ability to stay out of the way of the musical interaction and inspire the players with amazing orchestration .” — saxophonist Bob Mintzer. *

Gil Evans conducting, and letting in happen, in the early ’60s.

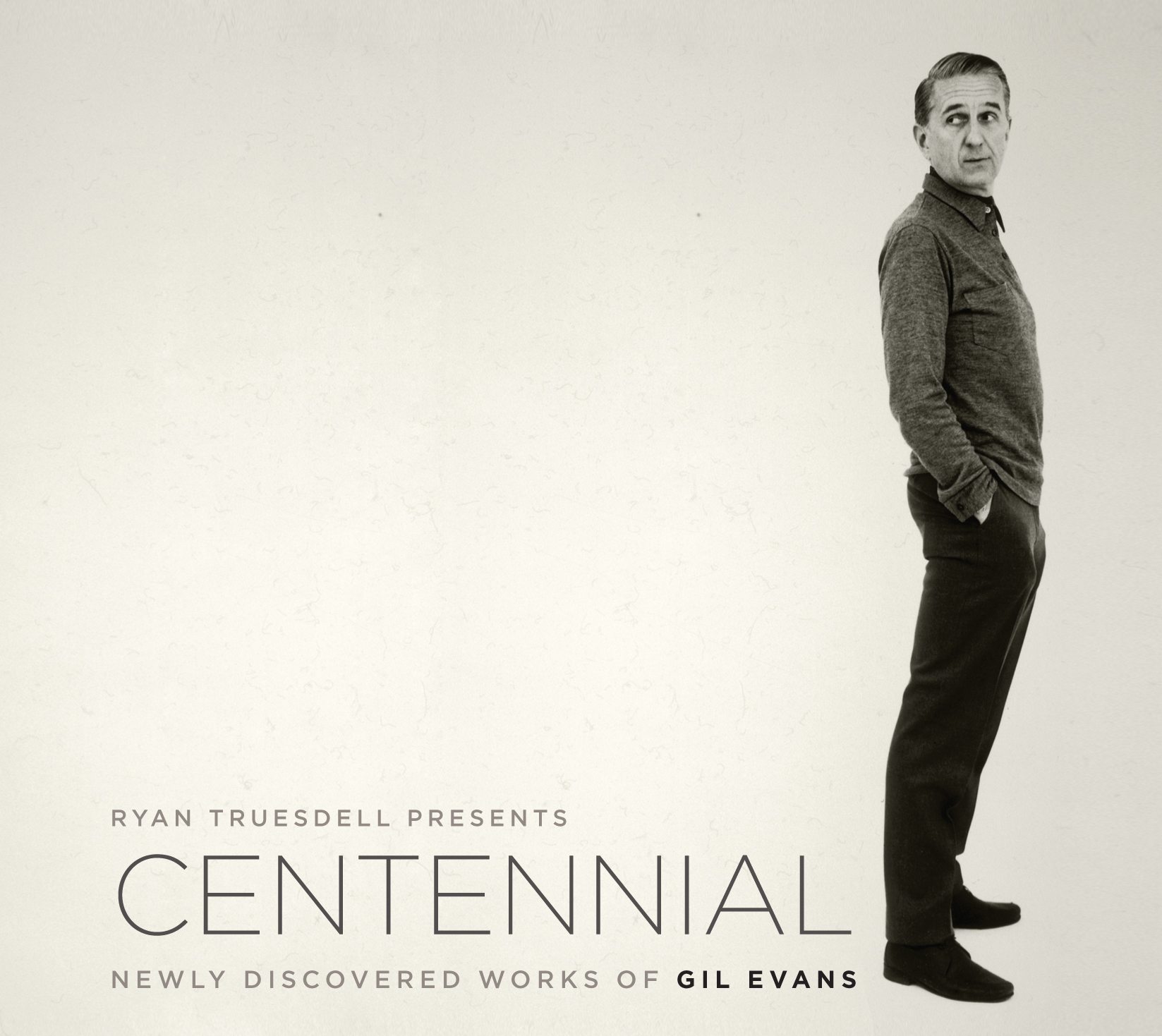

Ryan Truesdell /Gil Evans Project – Centennial : Newly Discovered Works of Gil Evans (artistShare)

In America there is individualism that begins selfishly, of necessity, but then stays selfish, feeding hubris and often greed. Then there is individualism that nurtures its own creativity and, when the time is right, shares it — feeds it into simpatico compatriots, who help make it great American culture, begetting wealth to be shared by generations.

The late Gil Evans was the godfather-Svengali of modern jazz arranging, the bridge between Debussy and Ellington to Vince Mendoza, Darcy James Argue and Maria Schneider, who helped realize this project. Evans’ brooding tapestries engulfed the stunning silhouettes of Miles Davis’ exquisite solos on Sketches of Spain and Porgy and Bess.

Evans’ exploratory affinities stretched to Hendrixian textures. Now, Ryan Truesdell (who studied with another great modern arranger, Bob Brookmeyer) has dug up early ‘60s scores from the Evans family archives. Centennial: Newly Discovered Works of Gil Evans almost brings Gil back to life in unheard material and re-casting of Evans classics, from the tabla-tinged “Punjab” to the world-weary “Smoking My Sad Cigarette” and Weill/Brecht’s “The Barbara Song,” whose sonic mysteries rise more full-throated than the original. Luxuriate in this.

As he studied these scores, Truesdell discovered “fascinating musical references and techniques that illuminated dimensions of Gil’s personality and gave me more insight into him as a person,” the arranger and conductor writes in the liner notes. So this music — with superb vocals by Kate McGarry and Luciana Souza and solos from pianist Frank Kimbrough, vibraphonist Joe Locke, and tenor saxophonist Donny McCaslin, among others — feels mighty damned true to Evans.

And yet, as thrilling as Centennial is to hear in all of its high-tech digital detail, there is something missing. That must be Evans himself — in the studio or on the bandstand. There’s an uncanniness to his own recordings that isn’t contained in the scores, I suspect. It was the jazz element — that of the leader with his players, hearing the voices in his head then subtly re-shaping and re-blending the colors to the strengths and even the moods of his musicians. The best Evans sounds like alchemy.

And here’s where the Duke Ellington connection comes in. Ellington knew precisely what to get out of the unique talents of each of his players. And they became greater players for that contextual opportunity. For example, the great saxophonist-composer Wayne Shorter probably learned a lot about dynamics and nuance in a large setting as a soloist in the original “The Barbara Song” on The Individualism of Gil Evans.

Here’s where Evans’ phantom Svengali -like sensitivity to the musical moment comes in, as Bob Mintzer notes above. And Like Ellington and Basie, he also played some of the greatest less-is-more orchestra leader jazz piano, his dense voicings and breathless grace notes infusing the players with evanescent Evans magic.

Or as Jim McNeely has said: “Some people consider me a pretty good composer/arranger. When I start to believe them, I put on ‘Barbara Song.’ To this day I am reduced to tears. It’s a humbling experience.”

Evans probably learned a large measure of those wizardly skills from studying The Duke. And from Claude Thornhill, when he began arranging in Thornhill’s ground-breaking orchestra. Here’s where you start hearing what Gunther Schuller described as the “subdued pastel-shaded backgrounds and low-register counter melodies” that would become part of his mature style. With a chamber music writer’s deftness, Evans would score striking contrasts of, say, bright clarinets against the darker-hued brass, horns and tuba, creating an odd intervallic spaciousness filling with billowing tonalities. 1

Evans, though hardly Ellington’s equal as a composer, clearly had his own genius, expanding Ellington’s vast sphere of influence into his own sonic galaxy. On “Individualism” alone, consider the strange range from winsomeness to debauchery evoked in “Flute Song/Hotel Me,” or the pensive Catalan clouds and piercing brass light shafts of the brief tone sketch “El Toreador.” And yet he could dig down and distill 90-proof essence of the blues, as in “Spoonful.”

And no one will ever retell the soulful, quintessentially American saga of Porgy and Bess in pure, worldless music as vividly is Evans and Davis did. Schneider, today’s most acclaimed jazz orchestra arranger/ composer, calls “P & G” her “favorite music on earth.”

Gil Evans and Miles Davis (on flugelhorn, right) making alchemy in the studio. Courtesy allaboutjazz.com

Gil Evans and Miles Davis (on flugelhorn, right) making alchemy in the studio. Courtesy allaboutjazz.com

Slightly less lovable perhaps is the more psychologically reflective Sketches of Spain. By turns stoic and heartbreaking in its eloquence, it touches on tragedy, so penetrating is its beauty.

The point is to start with Centennial — an exciting, revelatory addition to Evans’ legacy. But then, go back to the magnificent analog collaborations with Miles (including Miles Ahead and the pioneering Birth Of The Cool ), and to Evans’ own great albums, “Individualism”, Out of the Cool, Where Flamingos Fly, Svengali, Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix, 75th Birthday Concert…

Evans is the sort of quietly humble, pay-it-forward genius that individualist America needs today, as it always has.

________________________________

This article grew out of a review of a CD, Gil Evans Project, Centennial, originally published in the August 30 issue of tThe Shepherd Express in Milwaukee.

*Down Beat magazine, from “My Favorite Big-Band Album: 25 Essential Recordings” by Frank John Handley, April 2010. Mintzer’s quote is also from the same article. The Schneider quote is from Down Beat, “Gimme Five,” October 2000.

1. The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930-1945, Gunther Schuller, Oxford University Press, 1989 p. 756

Love This!

Hey I am so thrilled I found your webpage, I really

found you by error, while I was researching on Google for something else, Regardless I am here now and

would just like to say thanks for a fantastic post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love

the theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at the moment but I have book-marked it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read more, Please do keep up the awesome work.

Terrific paintings! This is the type of information that are meant to be shared across the internet. Shame on the seek engines for not positioning this put up upper! Come on over and talk over with my web site . Thank you =)

Bramy, I’m not sure what paintings you refer to because you supposedly commented on a musical post, but if you refer to Arshile Gorky or Clyfford Still, I couldn’t agree more.