The death of Dave Brubeck on Wednesday — Thursday was his 92nd birthday — summons indelible anecdotal memories, though I can’t resist mentioning that my voice recognition software just dictated his name as “debris back.”

A random shred of dark humor from the netherworld of electronics is something I doubt Brubeck would object to, as a man who exuded prodigious creativity, industry and generous spirit over his long, deeply influential career.

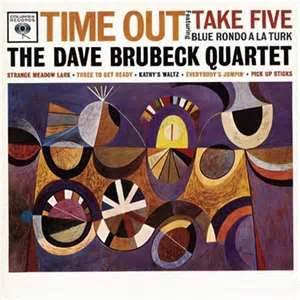

The first adolescent memory is of my father’s almost incessant playing of the 1959 Time Out album. I’m sure most of my six sisters have that peculiarly perfect tune’s 5/4 vamp etched in permanent memory. Years later, all of Norm’s favorite albums were stolen and presenting him, on his 80th birthday, Time Out on CD, gratified all of us. (It was also dad’s last birthday party, see photo at bottom, after notes).

Brubeck has said he had to cajole Columbia Records into releasing the album of odd-time signature tunes. It became the label’s biggest-selling jazz album of all time.*

Back when dad bought the Brubeck quartet’s LP Live at Carnegie Hall, he’d play all four sides on a Saturday morning during chores, and it’s surely the first concert-length live recording I ever experienced and absorbed. I recall especially the bounding, breathtaking 9/8 meter contractions of “Blue Rondo à la Turk.” Those two albums lit the fire for my lifelong passion for jazz.

Of course, as a baby boomer, I also quickly immersed in my own generation’s music and soon jumped to modern jazz as an essentially African-American art form. I came to understand that many white artists practiced this form on a par equal to anyone, but admit to becoming a bit of a Brubeck pooh-pooher. The rub was the seeming clunkiness of his attack on the piano (metronomic even, on “Take Five,” set against altoist Paul Desmond’s mellifluous swing, drummer Joe Morello’s deftly colored dynamics and the breathing pulse of the band’s black bassist, Eugene Wright.

Yet the tension created among these rhythmic and harmonic forces was palpable, and it was Brubeck who always pushed the edge of experimental time signatures that messed with conventional swing. Plus the often dense-voiced block chords he heaved from his piano gave a vibrance to dissonance, which often cast a forbidding aura in contemporary classical music.

I would later learn that the brilliant avant-garde jazz pianist-bandleader-composer Cecil Taylor counted Brubeck among his formative influences. At that point, I began to shed my bias about Brubeck’s alleged pianistic squareness.

Indeed my friend Frank Stemper, professor of composition at Southern Illinois University and a longtime jazz pianist, credits Brubeck with “the greatest (recorded) jazz piano solo ever,” on from that Carnegie Hall album, where on the seminal American standard “St. Louis Blues,”: “He’s soloing in four keys simultaneously — and swinging to boot.” Brubeck’s two-handed riot of sharp chordal counterpunching is stunning. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFrnCnbEJMQ

Brubeck shouldn’t be remembered as just a mathematical-musical nerd; his beguilingly romantic melody “In Your Own Sweet Way” has become a jazz standard.

Such forces keep a fan-turn-journalist on the Brubeck trail, which leads to the ultimate comedy of errors of my professional career. In the late 1980s, Brubeck and his musical sons Chris and Dan played a concert in Milwaukee double-billed with in fellow pianist Ellis Marsalis and his celebrated sons, Wynton and Branford (with younger bro Jason on drums).

The rare event cried out for a feature on “fathers and sons in jazz.” I pitched the story idea to Down Beat magazine which gave me a green light. So I arranged for post-concert interviews with representatives of both families.

I was fortunate enough to snag patriarch Ellis Marsalis and the voluble and intelligently opinionated Branford. I clicked my recorder button and began asking questions, and they gave me fine, thoughtful answers and I thought “Man, this is a great story.” Then, right at the end of the interview, Branford peered down at my recorder and said “Is that thing going?”

I looked down — I had hit the “play” button on the soundless blank tape rather than “record,” and never stopped to double check while juggling my two interview subjects. Against habit, I’d also failed to take any written notes.

I was aghast, and yet I still had an interview with the two Brubeck sons arranged. They agreed to slide over to Dunkin’ Donuts on Wisconsin Ave. My spirit lay quietly crushed and yet I remember Chris Brubeck, the bassist-trombonist who physically resembles his father, offering an exuberantly genial chat about life with old man Dave. I never mentioned the god-awful blunder tormenting me. Without the Marsalis material, the Down Beat story never materialized.

It’s a good, hard lesson for journalists – to take care of your business but I also take from that memory the generosity of both the Marsalises and the Brubecks, the latter sons whom I’m sure inherited much of that spirit from their father.

I won’t chronicle Dave Brubeck’s long, auspicious career and refer you to Ben Ratliff’s excellent New York Times obit piece for that. 1 But do recall Brubeck’s ahead-of-his-time explorations of world music forms, his sacred music a la Ellington, and his large compositions for social justice. One Brubeck cantata “Truth is Fallen,” “lamented the killing of student protesters at Kent State University in 1970, with a score including orchestral, electric guitars and police sirens,” Ratliff writes.

Fast forward to the third anecdote, which occurred just a few weeks ago, at Milwaukee’s fall Gallery Night opening reception at the King Drive Gallery for the fascinating and moving show of Underground Railroad-inspired quilts “Hidden In Plain View” (which I blogged about recently). A highlight of the event was alto saxophonist Larry Moore’s trio doing a soulful rendition of “Take Five,” squeezing all the bluesiness imaginable from that oddly percolating meter. The mostly African-American crowd ate it up. As the tensile flow rose, drummer Kim Zick soloed — quoting from Morello’s famous recorded solo of stutter phrasing and silence. Meanwhile, the black woman next to me spent virtually the whole tune tracing the 5/4 tempo with her forefinger moving up and down, to and fro.

There’s something powerful, elemental and beautiful about that rhythmic connection, which is a significant part of Dave Brubeck’s culture gap-bridging legacy (and, of course, that of Desmond, who wrote “Take Five.”) As Brubeck said, “The oneness of man can come through the rhythm of your heart.”

Ratliff comments about how, with the wildly popular Time Out album, Brubeck “saved jazz” at a time when the quintessential American art form was seemingly disappearing under the unruly barrage of rock ’n’ roll and, soon, the psychedelic fireworks, illuminations and delusions of the counterculture. Through it all Time Out sold steadily and Brubeck’s presence persisted, the almost cavernously wide grin and his equally smiling, bespectacled eyes, and the zeal with which he attacked the piano and helped reinvigorate the art form.

Yes, he played categorically “cool jazz” but he had as much smart muscle in his own musical style as anyone.

The pleasure that Brubeck transmitted, the depth of expression and revelation of form that he mustered, make for a career that time brands deeply into human consciousness — the surprising zenith of popularity, the long productivity and his high, irrepressible human spirit.

___________

Special thanks to John Kurzawa and Frank Stemper

*Columbia/Legacy this year issued two Dave Brubeck Quartet recordings, Their Last Time Out, and The Columbia Studio Albums Collection: 1955-1966.

Perhaps the last recording of Brubeck at the moment is Chris Brubeck’s Triple Play Live at Arthur Zankel Music Center ( in June of 2011) on Blue Forest Records. Material ranges from the stalwart blues “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” and “St. Louis Blues,” to Dave Brubeck’s Japanese-influence “Koto Song” to “Take Five” and “Blue Rondo à la Turk.”

photo (at top) of the classic Dave Brubeck Quartet (clockwise from bottom: Brubeck , Joe Morello, Paul Desmond, Eugene Wright) courtesy www.bluenotemusicblog.com

portrait photo of Brubeck from www. independent.com.

(Below) Norm Lynch’s 80th birthday party, July 20, 2009. Norm (1929-2009) is seated at center with Brubeck’s Time Out CD ( a gift from Nancy Aldrich) on table to his immediate left. Dad had hoped for an 81st birthday party.

photo courtesy of Anne Lynch

Kevin:

Thank you for the beautiful tribute to Dave Brubeck.

I saw the Brubeck Quartet play in Cincinnati some time ago. The show was breathtaking and the house was full. Interestingly, Dave Brubeck commented that he always took gigs scheduled in “odd time slots” because it was easier to get bookings that way. I thought…here is this icon Dave Brubeck’s perception of getting bookings for gigs. Really something.

Sheila Lynch

She, Over a long career even an icon has long dry spells of faded popularity (without a recent hit recording or whatever), which makes it tougher to get gigs. It’s a far less glamorous life than we suppose. Dave knew how to outsmart those dry spells.