CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH IN FEBRUARY

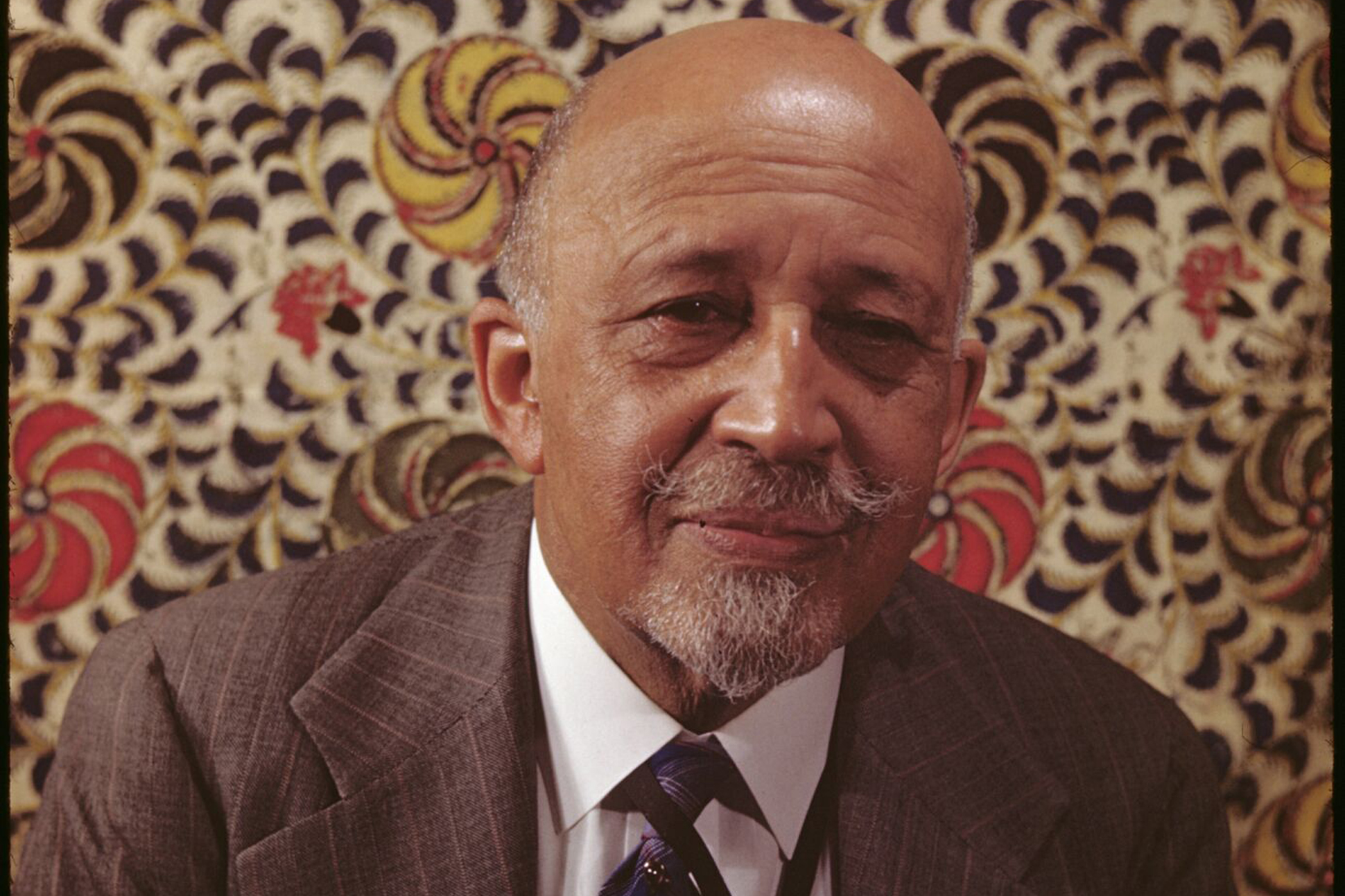

W.E.B. DuBois (February 23, 1869-August 27, 1963) Courtesy Poetry Foundation

Among the most vexing fears of some people on the right feeds into a visceral racism — their perception of miscegenation, the largely pejorative term for the mixing of racial bloods.

This fear stood on display perhaps no more nakedly than at the white supremacist march in Charlottesville in August 2017, where, among the chants was “blood and soil.” This is a Nazi slogan which asserted that ethnicity is based solely on blood descent and the territory one maintains.

The clash of two rally groups ended in a white supremacist killing an anti-Confederacy monument protester and seriously wounding 19 others, by driving a car into a crowd of protesters.

President Trump infamously declared that there were “good people on both sides,” clearly willing to cast his lot with the white supremacists who support him. White male working-class economic anxiety over potential competition from variously colored “others” seems to feed into this blood bias, which demagogue Trump regularly preys upon.

Today, February 23, the birthday of W.E.B. DuBois – the pioneering sociologist, civil rights leader, thinker and writer – offers time for historical reflection on this still-divisive issue of degrees of racial purity, because DuBois himself addressed it in an essay titled, with bold directness, “Miscegenation,” written in 1934.

At the time, the term was still the operative word for blood mixing through coupling of differing races. Du Bois wrote the essay for an Encyclopedia Sexualis, assembled by Victor Robinson, MD, of Atlanta University. Robinson requested the essay from DuBois, who sent it to him on January 10, 1934.

For reasons unknown, it went unpublished. It was finally published in 1985, in the collection of Du Bois work, Against Racism: Unpublished Essays, Papers, Addresses, 1887–1961.

DuBois’s “Against Racism” collection. Courtesy Amazon/ University of Massachusetts Press

DuBois’s “Miscegenation” is copiously researched, citing the work of many anthropologists and social scientists of the time. And urgency was rising to tackle the issue of mixed-blood society. In a few years, Hitler and the Nazis would begin their genocidal extermination of Jews, and their blitzkrieg of continental war. Many, except the most isolationist Americans, realized the Nazis posed a grave threat to freedom and democracy here and in Europe, but especially to any persons not deemed sufficiently pure-blooded Aryan by the Third Reich. This was a race war.

But what that purity instinct really meant vs. reality — its ignorance of a non-white’s humanity and radical rationalization against Jews — was little known to the general public, though DuBois was gathering fairly extensive ongoing research that would’ve reached a larger public in the encyclopedia.

Might the essay, if published, have spurred a spirited international debate and raised consciousness on the issue — affected public response to Fascism in Germany itself, and beyond?

Even now, the Against Racism collection isn’t very well known.

DuBois, a light-skinned black man clearly of mixed blood (his father was French-American and his mother Dutch, African and English), had natural interest in the subject. But he also earned two bachelor’s degrees, the second in history from Harvard and in 1895 became the first African-American to receive a PhD from Harvard. He became a controversial figure over his career for taking progressive political positions, including socialism, and especially in opposition to Booker T. Washington’s philosophy of black compliance to white privilege.

Courtesy Boston Review

Like many brilliant men, DuBois was just ahead of his time. His value system appraising African-American blood stood on the foundation previously laid in his 1924 book The Gift of Black Folk: The Negro in the Making of America, stating that the black folks’ gift to the world was “uniquely more moral and spiritual than that exemplified by any other of the groups. It was the gift of soul. Black folk had an unfailing faith in the world, ‘an unfaltering hope for betterment and a wide patience and tolerance for opposition and hatred.’ DuBois contended that it was black people who…made emancipation inevitable and made the modern world at least consider, if not only wholly accept, the idea of a democracy including men of all races and colors,” as David Levering Lewis explains in his biography W.E.B. DuBois: The Fight for Equality in the American Century, 1819-1963. 1.

Yet the black people’s “gift of soul” was somewhat known and felt, especially in their music by then, if too-infrequently articulated or acknowledged.

So, hard facts of life might be more to the point. In DuBois’ early masterpiece The Souls of Black Folk — which I taught to a fairly receptive cultural journalism class at Edgewood College in the late 2000s — he propounded his idea of black people’s every-waking-moment “double-consciousness” of their “otherness.”

In The Souls he also sums up from many specific examples, and understands how “people easily are misled from facts.” Note, in the extended quote here, DuBois’ striving for objectivity, despite his passion, even acknowledging the black folks “crimes,” while striving further to explain their meaning:

“We seldom study the condition of the Negro today honestly and carefully. It is so much easier to assume that we know it all. Or perhaps, having already reached conclusions in our own minds, we are loath to have them disturbed by facts. And yet how little we really know of these millions,— of their daily lives and longings, of their homely joys and sorrows, of their real shortcomings and the meaning of their crimes! All this we can only learn by intimate contact with the masses, and not by wholesale arguments covering millions separate in time and space, and differing widely in training and culture. Today, then, my reader, let us turn our faces to the Black Belt of Georgia and seek simply to know the condition of the black farm–laborers of one county there.” 2

Are their failings, and their triumphs, a matter of blood?

Now, think of our current environment of pervasive disinformation and “post-truth” conditions.

In DuBois’s 1934 essay “Miscegenation,” we learn of the latest research on the blood flowing to the brains and hearts of such descendants of slaves. He quotes from a book on mulattoes:

“…Ever since the existing human species diverged into its four or five existing varieties or sub-species, there has been been a constant opposite movement to unify the type. Whites have returned southward and mingled with Australoid, Australoid have united with, and produced Melanesians, and Papuans; and these, again, have mixed with proto-Caucasians, or with Mongols to form the Polynesian.The earliest types of white man have mingled with the primitive Mongol, or directly with the primitive Negro.”

There’s evidence of ancient Negroid strains, “in the features of mixed descendants at the present day, the fact is attested by skulls, skeletons and works of art of more or less great antiquity in France, Italy, etc…’ 3

DuBois’s essay is full of such citations with a modicum of his own comment or rhetoric. But he does anticipate the Nazi counter-narrative, which drew from E. H. Hankins, who “almost alone among current anthropologists tries to prove that physical differences mean mental differences.” That counter-intuitive theory never stood up under critical scrutiny.

“…race mixture among the Romans was more frequent in earlier history than later…The decline of Rome was certainly social and economic, rather than racial. Indeed, it is a tenable thesis to declare with Schneider, that at least some race mixture is a prerequisite to the German cultural development. Egypt, Babylon, and Western Asia show great race mixture.”

(Felix) Von Luscan says: “We all know that a certain mixture of blood has always been of great advantage to a nation. England France and Germany are equally distinguished for the variety of their racial elements.” 4

DuBois eventually gets to the deeply unsettled nation of Germany of 1934:

“If the great gift made by Jews to German culture (including Einstein, Mahler, and Kafka — whose novel The Trial presaged Fascism coming in the 1920s — though the latter two were born in Austria, like Hitler) there is absolutely no dispute. 5 On the other hand, it was also indisputable that present economic rivalry and racial jealousy give Hitler and his followers a whip today to drive the German people in clannish and cruel opposition to their Jewish fellow citizens.” 6

Franz Kafka’s “The Trial” as audiobook. Courtesy https://audiobookstore.com/

DuBois soon brings the argument around to the United States:

“The greater our ignorance of the facts, the more intense has been the dogmatism of the discussion. . indeed, the question of the extent to which whites and blacks in the United States have mingled their blood, and the results of this intermingling, past, present and future, is in many respects the crux of the so-called Negro problem in the United States. …most thinking Americans do not hate Negroes, or wish to retards their advance. They are glad slavery has disappeared; but their hesitation now is to how far complete social freedom and fill economic opportunity for the Negro is going to result in such racial amalgamation as to make America octoroon in blood. It is the real fear of this result and inherited resentment at its very possibility that keeps the race problem in America so terribly alive.” 7

Note my italics above, and then reflect. DuBois wrote in 1934.

Twenty years later, the seemingly irrational anxiety over American identity was analyzed by Richard Hofstadter in his influential essay “The Pseudo-Conservative Revolt — 1954”:

“What other country finds it so necessary to to create institutional rituals for the sole purpose of guaranteeing our nationality? Does the Frenchman or the Englishman or the Italian find it necessary to speak of himself as “one-hundred-percent” English, French or Italian?…When they disagree with one another over national policies, do they find it necessary to call one another un-English, un-French, un-Italian?” 8

Today, America’s always evolving and commingling nation of immigrants is inevitably much the closer to a predominantly octoroon society. And yet we still deal with the last stand of the angry, fearful white man, as embodied by the pseudo-Conservative white man in the White House.

______________

- David Levering Lewis, E.B. DuBois: The Fight for Equality in the American Century, 1819-1963. Henry Holt, 96

- E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, Dover Thrift Editions, Ch. 8, 84

- DuBois, Against Racism: Unpublished Essays, Papers, Addresses, 1887–1961, ed. Herbert Aptheker, University of Massachusetts Press, 91

- DuBois, ibid, 93

- The kangaroo court trial of Josef K. in The Trial brings to mind the willfully dysfunctional, undemocratic Senate impeachment “trial” of Donald Trump (sans evidence or witnesses) but with reverse outcome. Trump is “acquitted.” Josef K. is killed “like a dog.” The “justice” of the powerful vs. the powerless. Franz Kafka earned a law degree, but worked most of his life for an insurance company. In The Trial, there are “unaccountable functionaries, no juries, no hints of democratic government, not even a trial as the common law world thinks of it.”as Darryl Brown notes in “What Can The Trial Tell Us about the American Criminal System?” http://texaslawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Brown-93-2.pdf

- DuBois, Against Racism, 95

- DuBois, ibid, 96

- Richard Hofstadter, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Vintage, 59