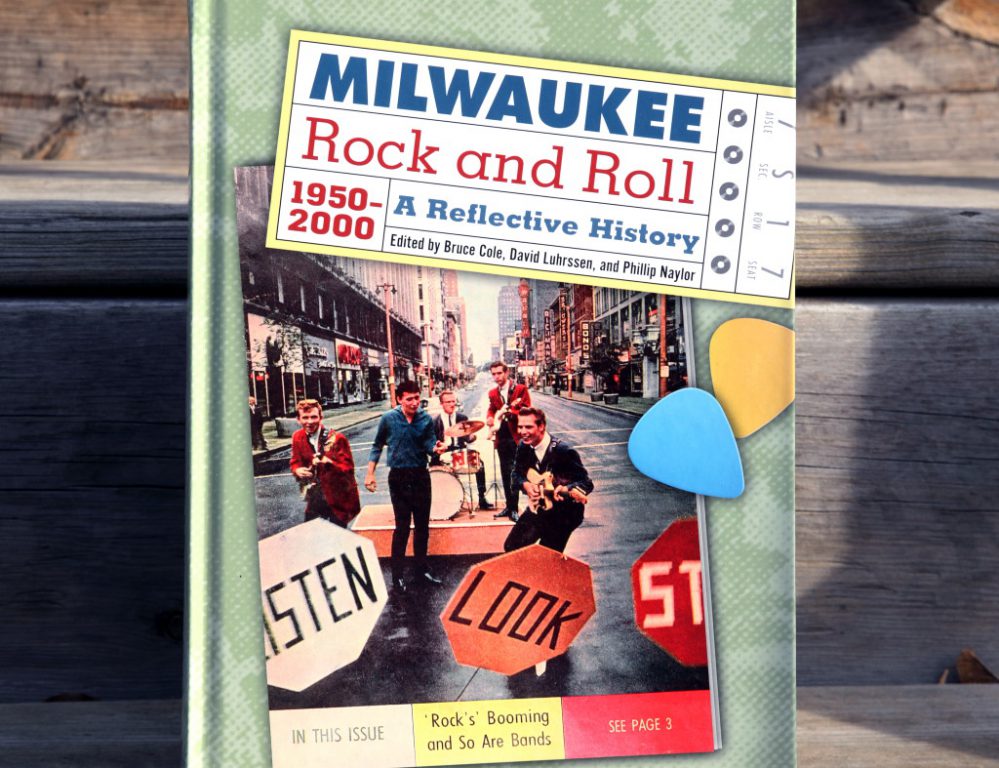

Photo courtesy urbanmilwaukee.com /Marquette University Press

Review: Milwaukee Rock and Roll 1950-2000: A Reflective History Edited by Bruce Cole, David Luhrssen, and Phillip Naylor. Marquette University Press. $29.95 hardcover

(Full disclosure: Kevernacular [Kevin Lynch] contributed a short chapter on Milwaukee jazz-rock fusion to this book, but was unpaid and will receive no profit from book sales)

Part 1

Imagine you have a time machine for Milwaukee rock ‘n’ roll – you can travel back to 1950, then forward to the turn of the 21st century. Imagine all the people telling this story, musicians who rocked your life, crazy and sage-like dee-jays, angel-devil club-owners, critics on the scene, and other experts. You can’t literally hear all the music, but the more you imagine you begin to hear it, certainly that which you experienced, and that music best described and evoked. The Time Machine is no big contraption, but a sleek, handsome book, a multi-colored gem.

Milwaukee Rock and Roll 1950-2000: A Reflective History is, as the subtitle suggests, not intended as a comprehensive, scholarly treatise on the subject. However, it brims with primary sources, and works well to rev imaginations and long-term memories, even of aging boomers. And it does tell a resonant, chronological story. Marquette University Press produced and organized it with rigorous care. I first wrote my short chapter on the city’s jazz-rock fusion scene three or four years ago. My text was revised with editorial oversight by MU history professor and musician Philip Naylor, who teaches a class on rock ‘n’ roll.

Naylor conceived of the idea many years ago, while visiting the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. “I saw an exhibit about rock in Ohio/Cleveland and thought that a similar exposition could be made regarding Milwaukee rock,” he recalls. Add in vernacular musics beyond this book’s considerable scope, and the truth emerges that this archetypal heartland city has its own distinctive musical identity. The other two book editors are Shepherd Express editor David Luhrssen, who covered the local music scene for decades, and Bruce Cole, a musician who played with many bands throughout those fifty years.

Cole, like Jimi Hendrix, might ask: Have you ever been experienced? Yes, Milwaukee, I have. So I’ll incorporate my own Cream City experience in contextualizing my review.

This one of the most enjoyably informative, evocative and just-plain-fun books I’ve ever read from a university press, and I have read plenty of those. A large part of the vibrancy derives from Marquette University’s treasure trove of historic visuals and documents on the subject, The Jean Cuje Milwaukee Music Collection, which Cole curates, with his “elephantine memory.”

So the book bubbles with images: a photo shot from behind the Beatles performing in Milwaukee in 1964, with female fans, crying and swooning, deep into the background; the rather gymnastic Mojo Men forming a human pyramid onstage; a photo of R&B radio station WAWA staff, with star DJ “Doctor Bop” in full medical regalia; radio station Top 40 lists; The GTOs, an all-female rock band sporting hot pants; a funny album cover for the Jim Liban Blues Combo’s Blues for Shut-ins; a comically bizarre poster for The Violent Femmes playing at the Milwaukee Jazz Gallery, and much more.

Milwaukee rock ’n’ roll is virtually as old as the art form itself, as this book makes abundantly clear, fertilizing the rootsy story with insightful chapters and brief essays.

Elm Grove rockabilly singer Bob Berendt began trying to break into the music business as a singer and songwriter shortly after the release of Elvis Presley’s first 45 rpm single on July 20, 1954. In 1961 he cut a record at the celebrated Cuca Studios (which produced The Fendermen’s “Muleskinner Blues” in 1960) in Sauk City, but he failed to chart. Berendt traveled to Nashville, but to no real breakthrough. Back home, he joined and contributed songs to The Royal Lancers, who the year before scored a regional hit with a cover of “I Fought the Law” (penned by Sonny Curtis of the Crickets) and later a national hit for Bobby Fuller in 1966.

The song’s success reveals that the subculture’s anti-establishment spirit clearly rose in Milwaukee by the early 1960s. City bands began incorporating R&R into their polka and C&W repertoires. The Noblemen likely made the city’s first recorded rock song “Thunder Wagon.” But Larry Lynne asserts that his band, the Bonnevilles, was probably Milwaukee’s first purely rock ’n’ roll band in 1958.

And talk about rock roots: “Wizard of Waukesha” Les Paul – a book unto himself – “invented” the solid-body electric guitar in 1934, a prototype for his iconic Gibson Les Paul guitar, arguably the most beautifully-designed electric guitar ever. 1

Milwaukee’s premiere rock-blues guitar virtuoso, Greg Koch, plays the famous Gibson guitar designed by Waukesha’s Les Paul at the Les Paul 100th Commemorative Anniversary concert in Waukesha. Photo by Jeff Dobbs, courtesy MU Press.

“Because of its aesthetics, guitarists can feel the resonance through the contoured top hugging the instrument to the body,” writes Luhrssen and the late Martin Jack Rosenblum. “The humbucking pickups give the Les Paul Gibson a deeper, wider, warmer sound than the trebly, piercing Fender Stratocaster…” For Les Paul, a guitar wasn’t a phallic symbol. It should be “your psychiatrist, mistress, housewife, and bartender.”

By the late ‘60s, the Les Paul was THE new guitar-of-choice for most guitar gods: Clapton, Page, Bloomfield, Beck, Allman, etc. However, Hendrix didn’t use it, being a lefty who held the lighter Stratocaster upside down, and flung it around like a matador’s banderilla.

A great Milwaukee star emerged very early, guitarist Sam McCue, or “The Fountainhead,” as Naylor grandly dubs him, founder of the first great Milwaukee rock band, The Legends. This brilliantly eclectic stylist incorporated Latin, Western swing, R&B, and rockabilly, not to mention Slovenian polka. McCue was later hired by The Everly Brothers and toured worldwide with them from 1964 to 1970, He also played with Chuck Berry and Johnny Cash and important local bands, New Blues and A.B. Skhy.

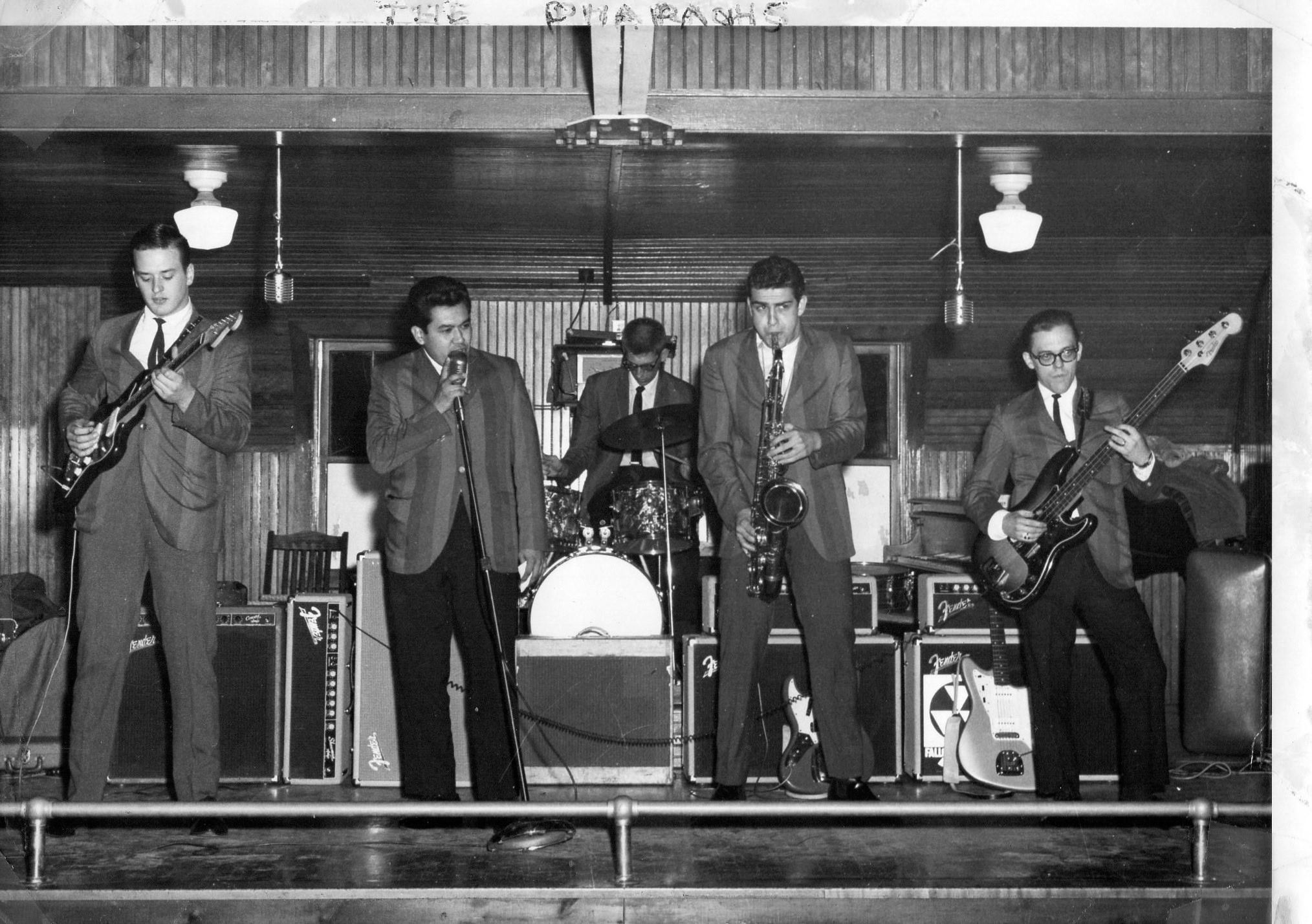

A culturally crucial early band was Little Artie and the Pharaohs, who first brought rhythm and blues style to crossover audiences, including working-class and suburban whites, blacks and Latinos.

Little Artie (on vocals, here) and the Pharaohs performing in the 1960s. Photo by Jim Lombard, courtesy MU Press

We also learn that Milwaukee played a role in the mid-’60s folk revival, with big thanks to the promoter Nick Topping, who first brought Bob Dylan to town, even if technical difficulties truncated the concert. Topping also developed a close relationship with Folkways Records founder Mo Asch.

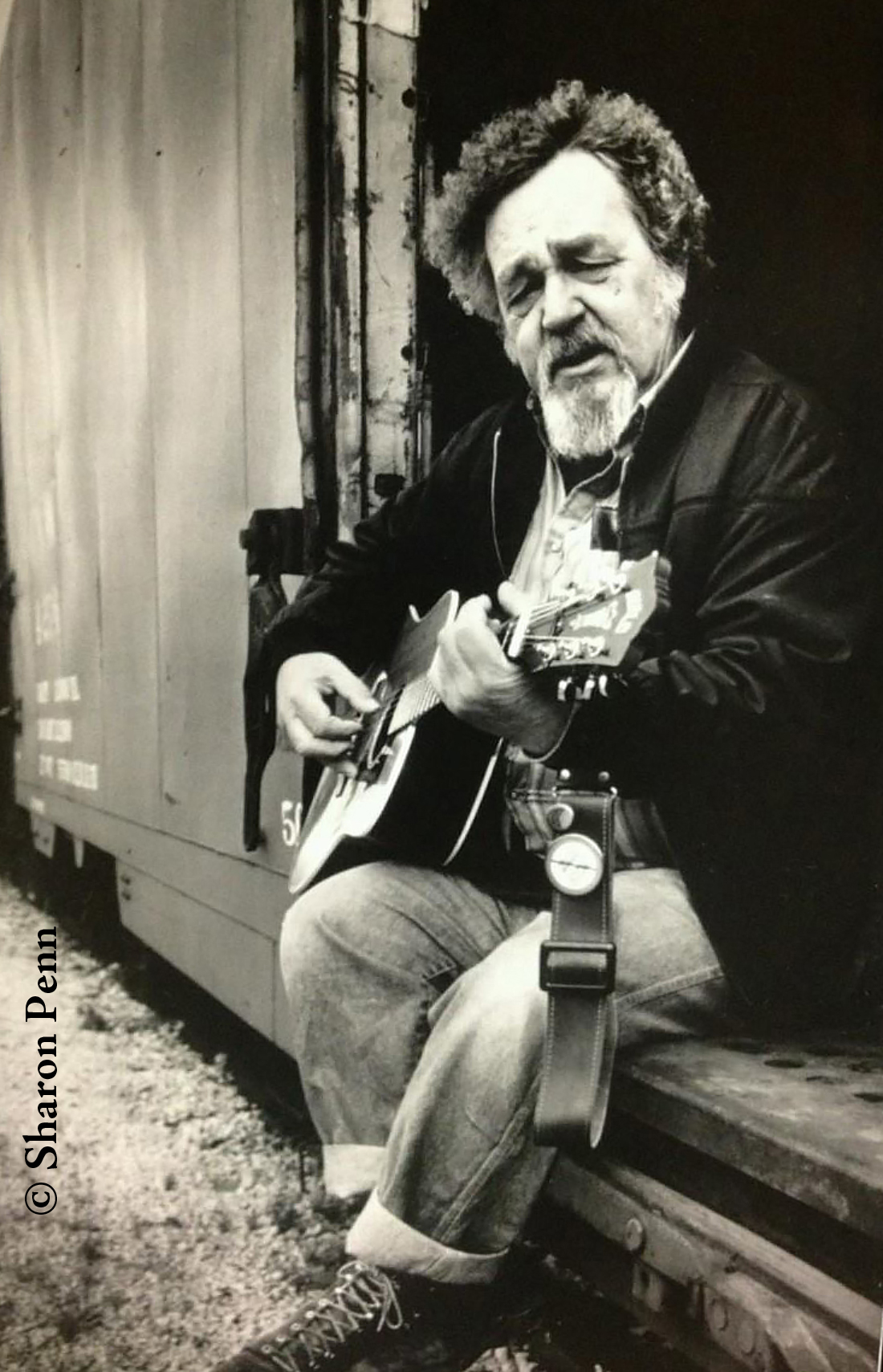

Milwaukee had its own Dylan in Larry Penn, who musician Lil’ Rev recalled as a “labor activist” and folk musician “who is the voice of a hard day’s work…” Like Dylan, Penn’s primary influence was Woody Guthrie, along with country blues giants Leadbelly and Mississippi John Hurt. Pete Seeger once declared: “Larry’s songs are as good as Woody’s.”

Pete Seeger called Milwaukeean Larry Penn’s songs “as good as Woody’s.” Courtesy Sharon Penn and the Larry Penn Archive/MU Press

Accordingly, Milwaukee developed other distinctive folk-rock talents like Jim Spencer, Barry Ollman, Bill Camplin and Willie Porter, the latter three still performing as “consummate artists,” as Johnny Carson used to say (Ollman still records, mainly online).

In Milwaukee and elsewhere in America, everything changed with the British Invasion. The Paul Revere of Milwaukee music was disc jockey Bob Barry, who first played the Beatles, Rolling Stones and the Dave Clark Five on WOKY 920 AM radio. He also hosted the 30-minute Beatles concert at the Arena in 1964, the stuff of legend. Milwaukee Journal prose stylist Gerald Kloss reported that “George would swing a lissome hip, or Paul would flash a sudden smile, and the roar from the crowd fractured the mortar between the bricks.” “BEATLES CONQUER THE CITY!” the morning Sentinel banner headline screamed. With all the photos and memorabilia reproduced here, including a ticket to the concert, you can pretend you were one of the thousands in the arena of insanity.

Of course, the British bands gradually helped young Americans to value their nation’s own indigenous rock sources: the blues, doo-wop, rockabilly, and country-western.

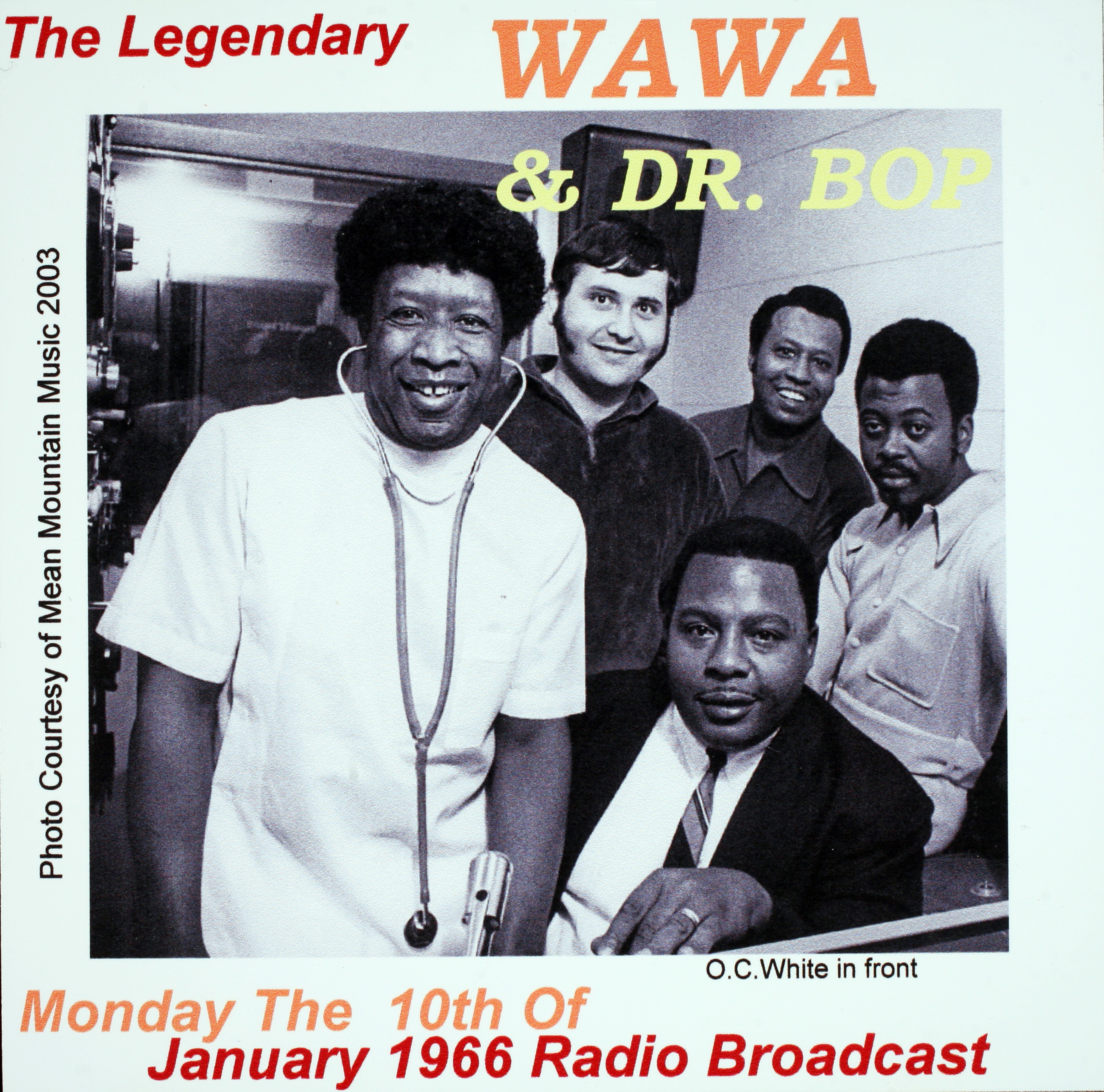

And local disc jockeys played a vital role, as pied pipers for anyone with a car radio or the new, affordable, fits-in-your-fist transistor radio (the precursor of Walkman and iPod). Beyond Barry, Milwaukee got hip to rhythm and blues when WAWA radio hit the air in the spring of 1960. The enlightened station played a variety of ethnic musics, connecting Milwaukeeans to their immigrant roots. WAWA’s smart, charismatic disk jockeys included program director O.C. White, and the irrepressible “famous Dr. Bop.” He would bellow into the mic, “I’m the cat with the fine-brown frame! I’m 42 across the chest, a stone-cold lover and an ex-Gold Glover. Bop be my name and music is my game! Doctor Bop powers on from the Soul Empire!”, as Jamie Lee Rake recounts.

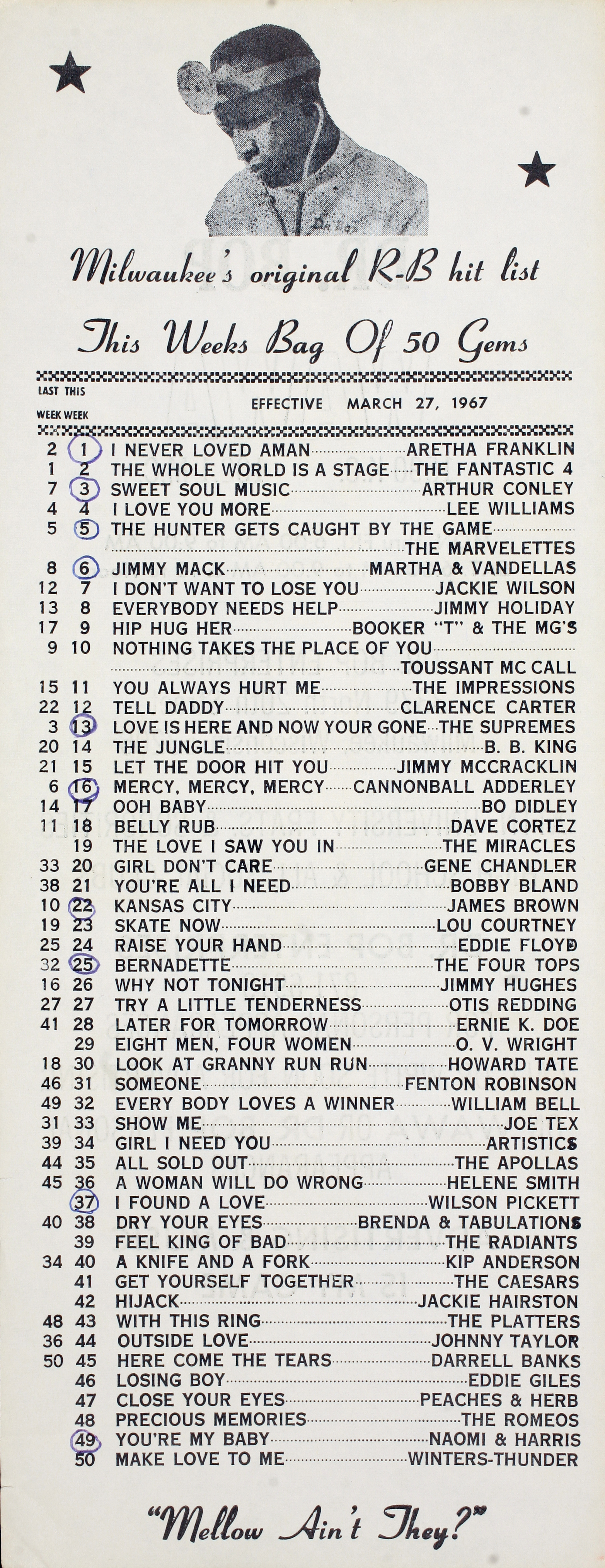

(Top) The staff of Milwaukee R&B radio station pioneer WAWA, in early 1966, including, front left, Dr. Bop (Hoyt Locke), and program director O.C. White, front right. Courtesy Mike Muskovitz of Mean Mountain Music. (Above) A Top 50 R&B chart for 45 rpm singles, from WAWA in 1967. Courtesy Stephen K. Hauser.

(Top) The staff of Milwaukee R&B radio station pioneer WAWA, in early 1966, including, front left, Dr. Bop (Hoyt Locke), and program director O.C. White, front right. Courtesy Mike Muskovitz of Mean Mountain Music. (Above) A Top 50 R&B chart for 45 rpm singles, from WAWA in 1967. Courtesy Stephen K. Hauser.

Dr. Bop captured the “say it loud” spirit of the new “black power,” but with the disarming comical flair of a Cassius Clay. And WAWA laid out the R&B like bloody ribs on a grill – hot, steaming and crackling with fire. WAWA, like the AM rock stations, also published their top singles lists, giving fans a reference for the happening jams to hear, and buy.

The inner city even got its own major record store, Radio Doctors “Soul Shop” on 3rd and North Avenue, where I worked after college, and where Dr. Bop would often promenade in, to pick up the latest hot 45s, and meet adoring fans. Radio Doctors owner Stu Glassman helped WAWA accurately compile their top sales charts as his two stores (the other at 3rd and State St.) sold by far the most R&B records in the state, as a “one stop” wholesaler and retailer. Green Bay Packer legend Willie Davis realized WAWA needed greater audience penetration, so his All-Pro Broadcasting eventually bought rights to the weak-signal station and turned it into a much more powerful FM station, WLUM.

I felt city folk’s growing connection to radio as a cultural lifeline, especially being a WLUM disk-jockey on the air the night news broke of Marvin Gaye’s death in 1977. I was the station’s second Sunday night jazz programmer, after jazz radio legend Ron Cuzner established an audience there for black and white listeners. “Contemporary urban music” had arrived in Milwaukee. 2

Such radio support helped buoy the city’s rhythm and blues soul, which began evolving into what would soon become the exponentially popular rap lyric-and-rhythm art of hip-hop by the mid-late ‘70s. The city’s first really notable rhythm and blues/soul group was the Esquires, which arose from harmonizing high school siblings, a la Chicago’s famous Impressions. The Esquires took a decade to seize on a song that blitzkrieged national charts, the exhilarating “Get On Up” in 1967, followed by a worthy sequel “And Get Away.” The first local talent to stand time’s test was Harvey Scales, who found a stylistic balance between Sam Cooke and James Brown, and cemented his legacy by penning “Disco Lady,” Johnny Taylor’s double platinum-selling hit and popular on the black TV show Soultrain. A deeply influential producer/musical polymath, Scales the performer never quite made it nationally, a distinction among local-born African-Americans that waited for Al Jarreau, who grew up on Reservoir St. overlooking the city he’d always love. When Radio Doctors “Soul Shop” got the first shipment of his autobiographical Warner Bros. debut album We Got By, we all knew this dude would do much more than get by. He deftly juggled jazz, pop and R&B styles to six Grammy awards.

Al Jarreau. Courtesy Al Jarreau Facebook Page.

Rake insightfully surveys local R&B development, from Black Earth Plus to the improbable undercurrents of white singer-songwriter Jim Spencer’s “Wrap Myself Up in Your Love,” a 12-inch single and a seductive production synthesis of disco, R&B and Tin Pan Alley, which “marked the shifts to urban music that reverberate to the present day,” Rake writes. Spencer’s recording employed white harp player Jim Liban and black drummer Kenny Baldwin, of already national-labeled Colour Radio, and owner of an important nightclub, The Starship, which facilitated the live-music transition to punk and early hip-hop.

Despite the city’s sadly still-deserved reputation for segregation, music has always provided cultural and social bridges among the races here, which politicians and other powers-that-be too-rarely heed or exploit. I delve into this in my own chapter, on the social and cultural impact of jazz-rock fusion. Like Jarreau’s long success, fusion’s peculiar synthesis of multi-racial genres had a more sophisticated yet high-energy style that you could groove to mentally, or often dance to. La Chazz brilliantly fused rock, jazz and salsa Afro-Cuban style, to connect Latinos to the scene. “As reed wizard Warren Wiegratz – who led Street Life, the long-time house band for the Milwaukee Bucks – explains of fusion, “The power of rock, with the freedom and the intelligence of jazz. What’s not like?”

Meanwhile, FM radio’s growing potential for wider, clearer and more creative communicative potential had evolved into the development of so-called free-form or “underground” FM programming. In Milwaukee, free-form’s avatar was Bob Reitman, which he remains today, on public radio WUWM, the same college station he first began expanding minds with, in long segments of uninterrupted music. Reitman first turned me and countless other listeners onto whole, literary programs of pure Bob Dylan; Reitman himself is an accomplished poet. Through Reitman we first heard long jam pieces, first from Chicago’s Butterfield Blues Band, the 1966 masterpiece “East-West,” a dynamically unfolding amalgam of blues, rock, Indian raga and John Coltrane jazz. Audiences were stunned by that band’s heightened creativity and musicianship, as were new San Francisco bands especially, which began experimenting with longer forms and sensibility, both introspective and expansive, influenced by mind-altering marijuana and LSD, a long, strange confluence across the youth culture landscape, especially in San Francisco’s 1967 “Summer of Love.”

Milwaukee rock radio avatar Bob Reitman. Courtesy onmilwaukee.com

End of Part 1 of a two-part review (The second part is the next posted article on this blog site.)

_________________________

The photos of the book cover, Al Jarreau and Bob Reitman are not from Milwaukee Rock and Roll. All other photos in this part of the review are from the book.