Kevernacular’s note:

Kevernacular’s note:

I interviewed Bill Monroe — born 98 years ago today — between his sets at Summerfest in 1981 for The Milwaukee Journal (published July, 5, 1981). He is credited for inventing bluegrass in 1939 when his Bluegrass Boys auditioned at the Grand Old Opry and caused a high, lonesome stir that has never quite died down, rather coming and going through American culture like the wandering winds of the Appalachian Mountains.

In 2000, it rose into a singing cyclone. The Coen Brothers movie O Brother, Where Art Thou? starring George Clooney — and its soundtrack of authentic hill country music — helped make bluegrass a pop phenom which hasn’t really abated, with the growth in American roots music and its increased popularity. 1

The soundtrack to a popular Coen Brothers film helped spur a bluegrass and roots music movement. Courtesy www.last.film.

Today the British popularizers Mumford & Sons are admittedly influenced by the American groups The Avett Brothers and Old Crow Medicine Show, whose instrumentation and vocal harmonies draw deeply on bluegrass.

The article helps to backdrop the impulses of today’s roots music. It was a close to the dawn of the mid-80s-to-early 90s roots music breakout but it speaks well of Monroe’s sense of cultural truth and inevitability at age 70.

Monroe was diagnosed with cancer in 1981, the year I interviewed him. I didn’t know it at the time and now wonder how it might have affected him during the interview. Feeling more vulnerable or more mortal? More reflective, accepting?

The interview is very important to me as I mark it as the first important step in my quest to get a foothold into the depths of American root music, before that term was really used. 2

I think the interview is all the more extraordinary because Monroe was legendarily resistant to interviews, even for annotators of his own albums. He had once threatened to break his mandolin over the head of a writer if he ever mentioned Monroe’s name in a book. Me, I guess I just got lucky, and because he’s now dead, his threats are history.

But Bill was lucky, too. After radiation treatment he survived for years. On April 7, 1990, Monroe performed for Farm Aid IV in Indianapolis, Indiana along with Willie Nelson, John Mellencamp, Neil Young and with many other artists. He died September 9, 1996 — after suffering a stroke in April of that year — just short of his 85th birthday, which was September 11, 1911.

Monroe felt his place in history had been abused and distorted too many times. Now I wonder if perhaps the cancer and his the sense of mortality led him to speak his mind, to set the record straight.

Bill Monroe (second from left) at the 1968 Newport Folk Festival. Newport’s seaside winds may have blown off his trademark Stetson. Courtesy Robert Corwin/PhotoArts.

Today his legacy is solidifying even if his still-surviving competitor Ralph Stanley is perceived by many as the father of bluegrass. But modern bluegrass singer and mandolin player Ricky Skaggs was one of many influenced by Monroe. Skaggs was only six years old when he first got to perform on stage with Monroe and his band. He stated, “I think Bill Monroe’s importance to American music is as important as someone like Robert Johnson was to blues, or Louis Armstrong. He was so influential: I think he’s probably the only musician that had a whole style of music named after his band.” 3

Bill Monroe and his mandolin. Courtesy www.popmatters.com

The following interview story, slightly edited by me, was headlined “Bluegrass Bill Springs A Surprise,” In the story, he sprung a surprise on singer Tom T. Hall, but the surprise is also that — despite his famously ornery reputation — he opens up the way he does, and shows he cares about the music and about communicating it to people of all ages.

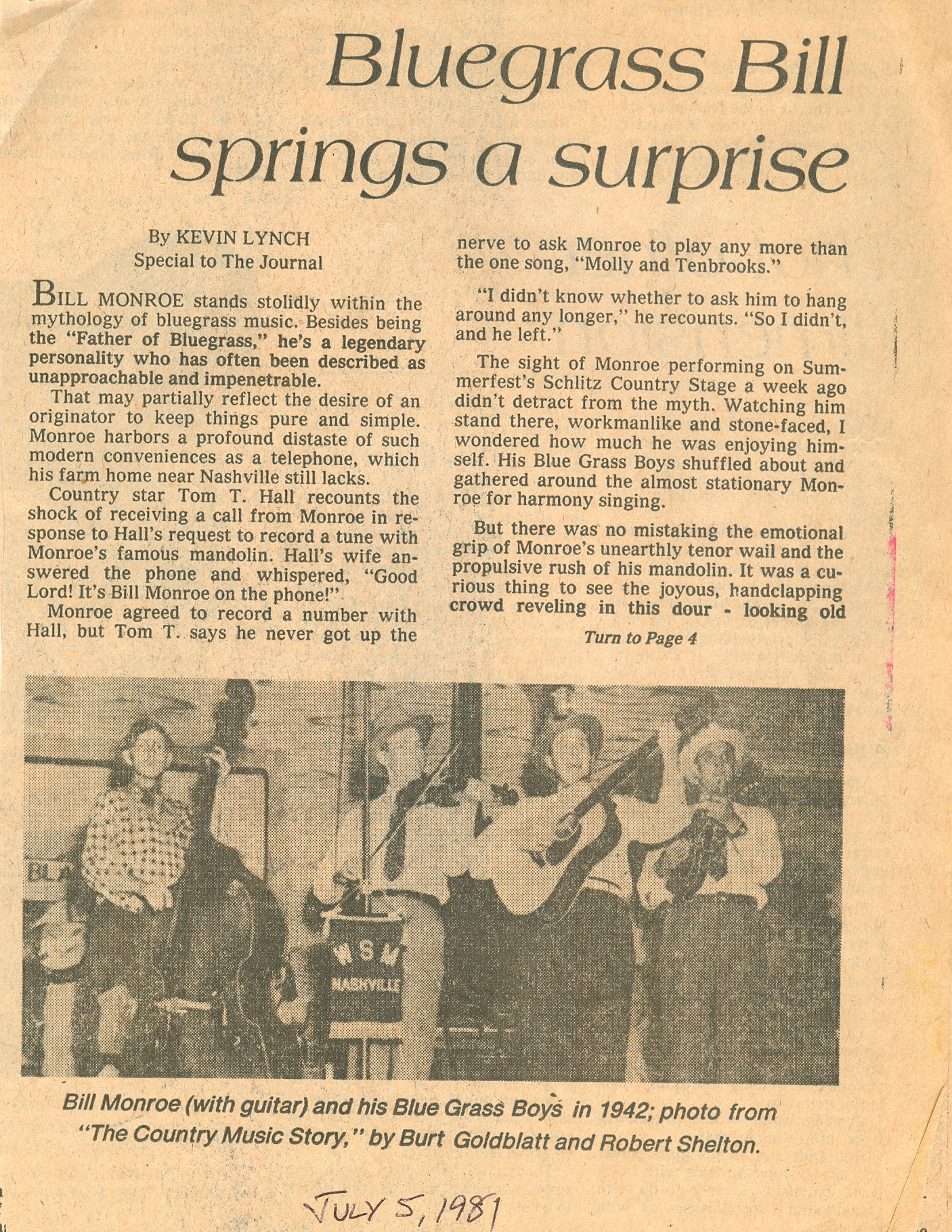

THE MILWAUKEE JOURNAL July 5, 1981

BIll Monroe Springs a Surprise

Bill Monroe stands centrally within the mythology of bluegrass music. Besides being “The Father of Bluegrass;’ he’s a legendary personality whose famously inpenetrable reticence may have partially reflected the desire of an originator to keep things pure and simple. Monroe harbors a profound distaste of such modern conveniences as a telephone, which his farm home near Nashville still lacks.

Country star Tom T. Hall recounts the shock of even a call from his old friend in response to Hall’s request to record a tune on Monroe’s famous mandolin. His wife answered the phone and whispered, “Good Lord! It’s Bill Monroe on the phone!”

But the sight of Monroe performing on the Summerfest Schlitz Country stage a week ago didn’t detract from the myth. Watching him stand there, workmanlike and stone-faced, I wondered how much he was enjoying himself. His Bluegrass Boys shuffled about and gathered around the almost stationary Monroe for harmony singing.

But there was no mistaking emotional grip of Monroe’s unearthly tenor wail and the propulsive rush of his mandolin. It was a curious thing to see the joyous, hand-clapping crowd reveling in this dour-looking old man. But the power of music works in mysterious ways.

I prudently eschewed such a newfangled contraption as a tape recorder in preparing for a backstage interview.

“He’s an ornery old fella,” Schlitz stage manager Bill Gorman told me, with an assuring smile. He introduced us and, with a trace of trepidation, I shook Monroe’s hand.

“It’s a pleasure to know you, sir,” he said immediately. Monroe was now wearing thick glasses (possibly for cataracts) and they softened his stoic demeanor. He munched on cold cuts and sipped coffee and I hoped refreshment had softened his attitude. We both stood there for several long seconds until I asked, “Uh, shall we sit down?”

“Oh, please have a seat,” he said. I sat down. The white-Stetsoned Monroe towered over me, still chomping silently on the cold cuts. Clearly, he had no intention of taking a seat.

“Just got into town on your bus?” I asked, clutching at the first question that came to mind.

“Yes sir.”

Yes sir. I smiled inside. The grand old man of bluegrass standing in a suit and neat dark tie proffering the term” sir” to a blue-jeaned, tennis-shoed reporter no older than his grandson. What was in your mind when you came up with the idea of bluegrass, I asked him. His answer reflected his notoriously reclusive nature.

“Well, I wanted music of my own to build around myself. I was gonna keep in the things I wanted and keep out the things I didn’t want.”

“Stonewall Jackson plays Bluegrass,” I thought, and tenuously pressed him a bit further.

“I wanted a hard-driving sound,” he said, “Fast work and fast playing keep up the feeling.”

I nodded in agreement and then he seemed to soften. “You know, bluegrass is awful close to gospel music in its sound and tone; you can hear that.”

Do you think your famous high, lonesome sound came out of your life situation at the time?

“There is blues in the music too, that touches a lot of feelings,” Monroe said. He looked away and continued. “I grew up on an old farm in Kentucky and there wasn’t nobody to visit with except the old folks and a few critters.

“I was the youngest one by eight years, the rest were long gone. I was sort of out on my own. It was kind of a sad, hard life. I had to work plenty out in the fields, where I could sing all I wanted…”

He stopped, as if suddenly realizing that he was tipping a hand he normally holds close to his vest. I asked him whether he felt he plays for a particular audience or for anyone who’ll listen.

“I like to play to everyone,” he said. “But I really like to touch good, decent people.” He paused again and the slightly muffled din of Summerfest more than filled the silence as he reflected. “I like to play to people that are sober.”

Bill Monroe (left) on a tour train with Dana Cupp, the last banjo player he ever recruited for The Bluegrass Boys. www. genelowinger.com. Photo courtesy of Gene Lowinger.

Monroe spoke diplomatically about the rise and dissemination of bluegrass music. He indicated a clear preference for the pure form as he created it, but voiced no ill will towards popularizers.

I asked him how a country man dealt with nationwide touring and the ways of city people.

“Well, now, I’ve been in this business a long time,” he said. “Since I invented this music in 1939 I’ve gained the respect of Northern people. They don’t try to outsmart me or put anything over on me. They realize we’ve got to be friends; that’s the only way were going to get together on anything.”

Did he think the rise in popularity of bluegrass and country music indicates any new attitude in Americans about the way they want the world to be?

“Well, the music has changed an awful lot since ‘39 and the world has changed a lot too,” he said. A white-hatted Blue Grass Boy stuck his head in the doorway, beckoning Monroe to come along for the last set.

Bill appeared to want to think about the question a bit longer, but the door was open now, and the buzz of the crowd seemed to draw him like a magnet. The manner quickly turned from reflective to curtly cordial.

“You tell the people here I just want to be their friend and I’ll come any time to play,” he said.” I want you to hear my new album. It’s called Master of Bluegrass, on MCA Records, 4 and it’s talking to the old folks and the young folks. Next time I’m back you tell me what you think of it.”

Monroe warms up with his Bluegrass Boys about the time I interviewed him in Milwaukee at Summerfest. Photo courtesy of Gene Lowinger*

I took the little pitch in stride because I felt that he did care what I thought. He met my eyes once more with a nod, and he struck me as being a shy man far more than a cold, standoffish one.

Heading to the stage, Monroe tucked his glasses in a pocket and his shyness inside the role of “The Father of Bluegrass.” With a strong grip on his mandolin, he can sing all he wants.

__________________

Here’s Monroe in an extraordinary solo performance of the classic “Wayfaring Stranger in 1989, eight years after I interviewed him. Courtesy vintage18lover.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LI92oDdXazg&list=TLDOvtqk289uU

________

1.By 2000 Monroe was dead, but the T-Bone Burnett-produced soundtrack to O Brother, Where Art Thou? includes, among others, Ralph Stanley, Alison Krauss, Gillian Welch, Emmylou Harris, The Stanley Brothers, John Hartford, James Carter & the Prisoners, The Fairfield Four, Norman Blake and singer-guitarist Dan Tyminski, who dubbed for actor George Clooney, who plays an escaped prisoner and a member of the fictional Soggy Bottom Boys.

2. Thanks to Milwaukee Journal editors Dominique Noth and Steve Byers, who sent me a very laudatory note after the article was published.

3. Du Noyer, Paul (2003). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music (1st ed.). Fulham, London: Flame Tree Publishing. p. 196. ISBN 1-904041-96-5. via Wikipedia.

4. Master of Bluegrass is available on the Bill Monroe box set My Last Days on Earth 1981-1994 on Bear Family Records.

What is the update on the Bill Monroe Movie by T. Bone Burnett?

Good question Margo. If I find out I’ll let you know.