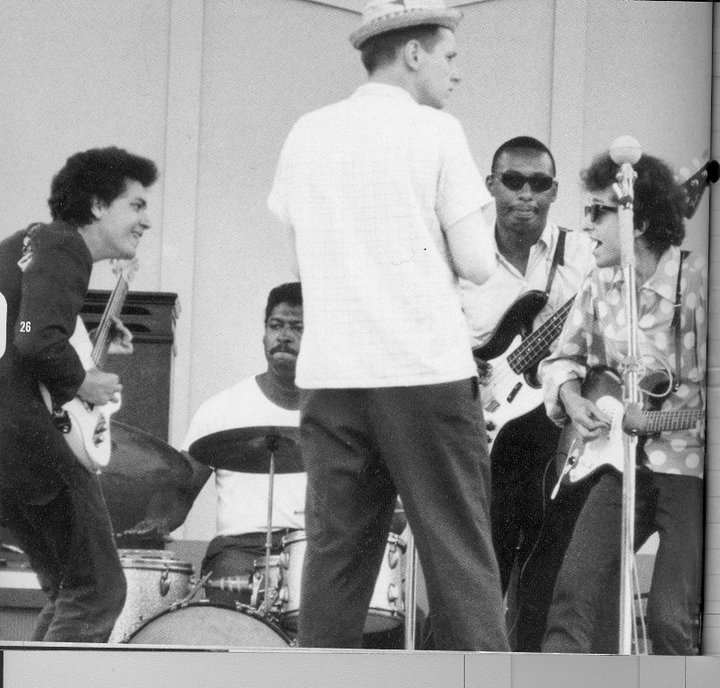

I’m in a reflective mood and just ran across my favorite photograph of the tragic guitar great Michael Bloomfield, a man who’s always spoken to me for various reasons. Well, this photo is a close number one ahead of the famous shot (below) of Bloomfield playing and jivin’ with Bob Dylan when he infamously went electric at The Newport Folk Festival in 1965. Bloomfield and Dylan cranked up the electric venom on “Maggie’s Farm” and, after that shock treatment, folk music was never the same again. A hoary but sometimes beautiful new creature was born: folk-rock.

(Musicians left to right) Michael Bloomfield, Sam Lay, Jerome Arnold, Bob Dylan. Pinterest

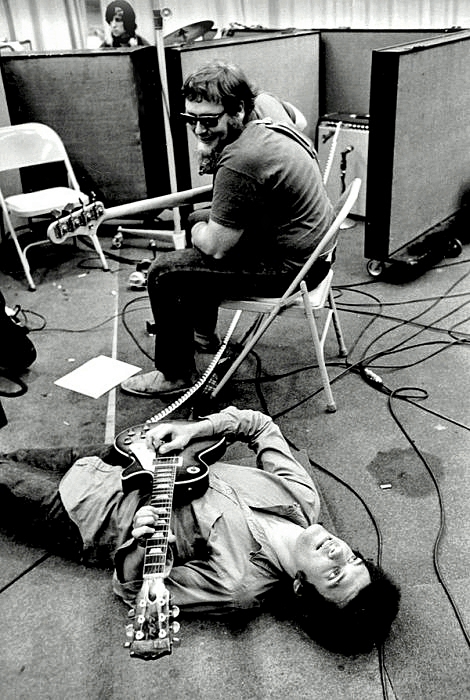

As for the revealing and, for me. rather moving Jim Marshall photo at top, it was taken at the famous Super Session recording with bassist Harvey Brooks affectionately needling Michael.

Bloomfield’s utterly chilled, prone position speaks volumes about the man: enduring extreme, chronic insomnia and drug addiction in the making. It also speaks to the man’s creativity and profound love for the music, especially the blues.

I would think Michael Bloomfield – the Jewish boy from Chicago, as much as any white man – bled blue.

The story continues to unfold: Michael lies amid the maze of wires, with a faraway gaze, a cigarette put out, or simply dropped, in the pool of spilled coffee on the floor. What are his eyes fixed on? What sort of vision hovers, almost taunting him with its distant guitar utopia? It would be fascinating to hear what he was actually playing at that moment, and what those phrases had to say. The man was clearly suffering, but persevering, for the time being, channeling his pain into the music, transforming it into something vibrant and redemptive, the essence of the blues.

Bloomfield played as well as he ever has that day, but could not even complete a whole recording session. Not long after this photo was shot, he informed singer-organist Al Kooper that he couldn’t continue, and Stephen Stills had to be called, finish what would become side two of Super Session.

It’s worth noting why this was to be called Super Session. Kooper, Bloomfield and Brooks had all achieved fame by recording Bob Dylan”s Highway 61 Revisited album, and the song that carved a mountain in the middle of the highway of rock music, called “Like a Rollling Stone.”

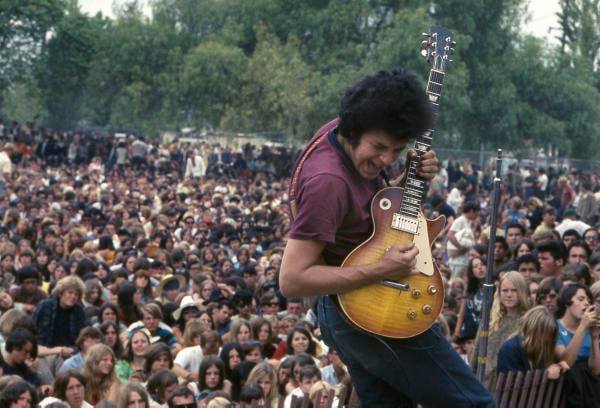

Soon afterward, Bloomfield became a freshly-crowned guitar god with the Butterfield Blues Band, which I’ll get to shortly. Although he started with Dylan and Butterfield playing the edgier Fender telecaster guitar (see photo with Dylan) it was with Les Paul’s Gibson guitar that Bloomfield found his true voice, in what he himself termed “sweet blues,” the sound for which you wanted most to be known. A biographical film is titled Sweet Blues: A Film About Michael Bloomfield. Kooper had formed pioneering jazz-rock bands, The Blues Project and Blood, Sweat and Tears, though he left the latter group early on.

The Les Paul guitar’s comparatively clean, singing tone replicated somewhat that of Bloomfield’s idol, B.B. King, who played a different sort of Gibson guitar. Waukeshan Les Paul’s gorgeously-sculpted physical creation allowed for a sonic vividness that captivated most leading rock guitarists at the time, who could all be seen playing the Les Paul shortly after Bloomfield took it up.

Another favorite Bloomfield shot reveals the man’s brilliant blues passion, at a rock fest with the Electric Flag in Santa Rosa, California.

The superbly produced Super Session is a great example of the guitar’s voice in the extraordinarily simpatico hands of Bloomfield.

How good was Bloomfield? Bob Dylan called him the best guitarist he’d ever hear. Or let’s hear Miles Davis, in his float-like-a-butterfly, sting-like-a-bee bluntness: “You could put Michael Bloomfield with James Brown and he’d be a motherfucker.”

To answer more personally, I now must refer backwards, to what would become his career masterpiece, the long instrumental piece “East-West,” which Bloomfield composed in 1966, as the title tune of the Butterfield Blues Band’s second album.

I have discussed the tune in a previous blog about the anthology box set Michael Bloomfield: From the Heart to the Head to the Hand. But what I wanted to say now, in light of the photograph above, is that he may have realized that “East-West,” composed while he was still in his 20s, was the pinnacle of his career. He would go on to play plenty, including Super Session, and great live follow-up albums for Columbia Records with Kooper, Taj Mahal and others.

He then formed the jazz-rock-R&B band The Electric Flag, but he was poorly suited as a long-term bandleader. So he embarked on a substantial solo career, as a scholarly maven of blues, of virtually all stripes. But because he intuitively fled from the personal spotlight like a heart-of-gold blues vampire (ergo the frequent nocturnal existence?), he remains underappreciated to this day.

But the masterful blend of Ravi Shankar’s Eastern classical music, rock and John Coltrane’s modal music that became “East-West” also reveals something of the man in the photo above. The composition was famously created in a sleepless all-night jam and composing session, and one can imagine Bloomfield, in the wee hours, on the floor with his Les Paul again. Something mysterious arose that night. I believe Elvin Bishop, who brilliantly shares lead guitar duties on the piece, in a much grittier style, has related how the piece welled up out of Michael as well as becoming a courageous labor of stylistic synthesis:

“We listened to Ravi Shankar and Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. Everything, you know? So yeah, it was cool,” Bishop recalled.

“But I’ll tell you the honest truth: the only person in the band who had any kind of clue about Indian music was Bloomfield, and his knowledge was …you know, you don’t really get into Indian music; it takes years and years. But the groove of the thing was based on a common blues thing in Chicago. A lot of times there would be a little revue happening, with a basic band and two or three different front guys; one of them would have a good name. And there was always what they called a “shake dancer,” a girl doing exotic dancing somewhere in the mix. The groove that starts out ‘East-West’ came from that. They would play an ‘exotic’ groove, something similar to ‘Caravan.” 1

For its diverse and unassuming roots, the piece is superbly realized as an extended composition. At times, it blazes like a house of blues afire, dueling with sun gods. Yet what always gets me is the quiet passages of the piece, which is miked so closely by producer Paul Rothschild that you can almost hear hear Bloomfield breathe, as he’s hunched over his Les Paul, in his typical manner. He played with tenderness, a balance of reverence and abandon, and assurance in the face of his personal abyss, and the sunburst of musical possibilities.

He had unlocked the doors of perception, between two great cultural traditions, and turned vernacular musics into high, revelatory art. “East-West” influenced countless musicians, and the nether blooming directions of creative popular music. Contextualized further, there had been no instrumental works as ambitious as this in American vernacular music in 1966. Few comparable works since have been as artistically successful.

Here it is. I recommend a hearty volume to get the full impact of the music’s wide dynamic range:

(L-R) Bassist Harvey Brooks, guitarist-singer-bandleader Michael Bloomfield, and singer Nick Gravenites of the newly-formed Electric Flag, probably shortly before they performed at the iconic Monterey Pop Festival in 1966. Facebook: Not Necessarily Stoned, but Beautiful: Hippies of the 60s and Beyond

I also just came across a third photo, which I decided to include because it is perhaps more upbeat, yet still complex. It shows Bloomfield with Brooks and singer-songwriter Nick Gravenites (who is credited with co-composing “East-West.”), about the time they had formed The Electric Flag, following all the music previously discussed. It was a marvelous group, bursting with grimy soul and ingenious jazzy finesse, but all too-short-lived. You can see the weight of life bearing down on Bloomfield, as a still-young man in his 30s. He was far from finished, but perhaps his fate was sealed.

He died in in his car, alone on a San Francisco street, of a drug overdose at age 37.

“Heroin, be the death of me.” — Lou Reed, The Velvet Underground

_____

Christopher Porterfield on the road. milwaukeerecord.com

Christopher Porterfield on the road. milwaukeerecord.com

Liner photo from James McMurtry’s “Complicated Game.” Photo by Shane McCauley

Liner photo from James McMurtry’s “Complicated Game.” Photo by Shane McCauley

James McMurtry. Courtesy youtube.com

James McMurtry. Courtesy youtube.com James McMurtry live at The High Noon Saloon in Madison with guitarist Tim Holt. Photo by Marc Eisen.

James McMurtry live at The High Noon Saloon in Madison with guitarist Tim Holt. Photo by Marc Eisen.