In their strange ways, dreams often surge, straining aloft, then soar, as if the elements have conspired in transcendent harmony. Of course, the same dreams more often than not hit tough crosscurrents or facing gusts that render the journey near endless and, by morning, nigh impossible.

Pardon my slightly self-conscious ruminations, which allude to my own relative capabilities as a writer. And I offer the typical dream scenario as a humble homage to a man who gazes down from a lofty stratosphere upon most other writers of his sort.

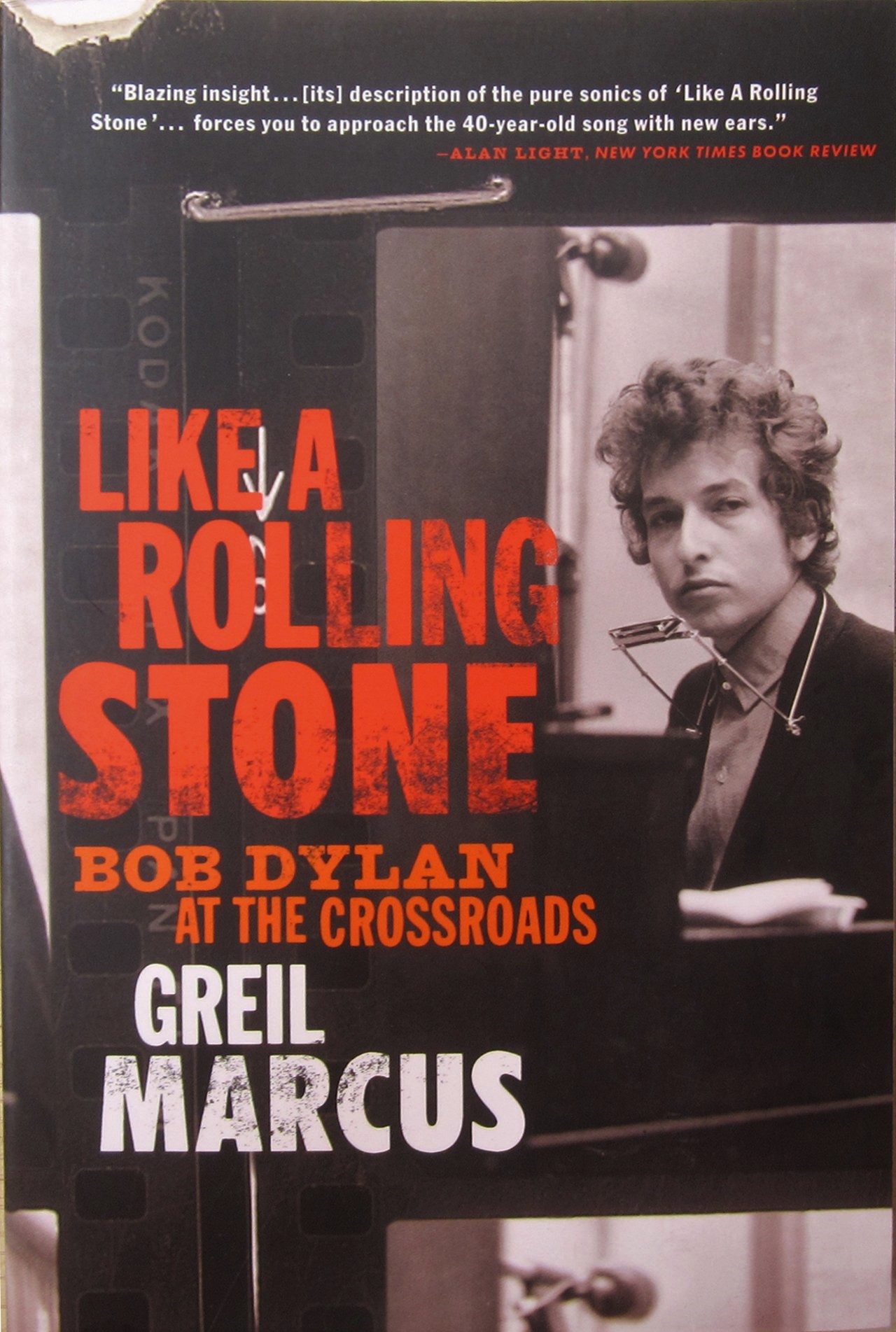

Greil Marcus remains one of the truly stupendous talents in music writing. He is well known for several extraordinary works including Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music; The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan and the Basement Tapes; and the truly epic work of cultural history, A New Literary History of America, a collaborative work that he co-edited. Another marvelous book Marcus co-edited, with the superb historian Sean Wilentz, is the Rose & the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad which includes a CD collection of ballads..

More recently he took on Dylan again with an extraordinary hyper-close reading that is equally expansive — a book length delving into Dylan’s perhaps generation-defining, or challenging, work “Like a Rolling Stone.” The song’s title endows the book, which is subtitled Bob Dylan at the Crossroads.1 The song is seared into my generation’s collective consciousness. Countless among us must face the crossroads with no direction home, and endure the howling wind ravaging our souls, blasting grit in our teeth, hoisting our boot heels in the clamor of chaos.

________

All the while Marcus rides the rolling beast like a master equestrian. His subtitle is cannily framed as Bob Dylan arriving at the mythical crossroads that Robert Johnson met the devil at and sold his soul for his transcendent musical talent, something one can almost imagine Dylan doing as well. The crossroads is real, as he persuasively tells it, nothing less than Highway 61 (as immortalized in his 1965 “Rolling Stone” album Highway 61 Revisited) and Highway 49, in Clarksdale, in the Mississippi Delta.

Photo of Three Blues Crossroads, Hwys 61 and 49. Photo by Carolyn Earle.

I must abject myself, as I often write in the same critical idiom and on similar subjects as Marcus. But his words will do the walking here, and glisten in the glory of the light they project, bejeweled with their innate fire.

It’s worth taking a few deep breaths to try taking in his description of “Like a Rolling Stone” as whole as we can, to feel the weight of his depths and embrace it with our straining mind muscles a bit. It’s also worth pausing to savor and ponder.

So now I stand back, and dictate:

“With “Like a Rolling Stone” too, it’s six minutes – six minutes to break the limits of what could go on the radio, of what kind of story the radio could tell…is the beginning and the end of what the record is about and what it is for. When the record is over, when it disappears into the clamor of its own fade to silence…you feel as if you have traversed the whole of a country that is neither strange nor foreign, because it is self-evidently your own – even if, in the first three minutes, the journey only went as far as your own city limits. The pace is about to pick up.

When “like a Rolling Stone” smashes into its third verse everything is changed. The mystery tramp who appeared out of nowhere at the end of the second verse has left his cousins all over this one. Everyone has a strange name, everyone is a riddle, there is nobody you recognize, but everybody seems to know who you are. ” You –” Dylan shouts, riding over the hump of the second chorus and into the third verse; the increase in vehemence caused by something so tiny as the adding of a syllable of frustration to the already accusing “you” is proof of how much pressure has built up. The sound Bloomfield makes is like Daisy’s voice – “the sound of money” – and like Gatsby Bloomfield is reaching for it, but as soon as it is in the air he steps back from it, counting off the beat as if he is just James Gatz, counting his pennies.

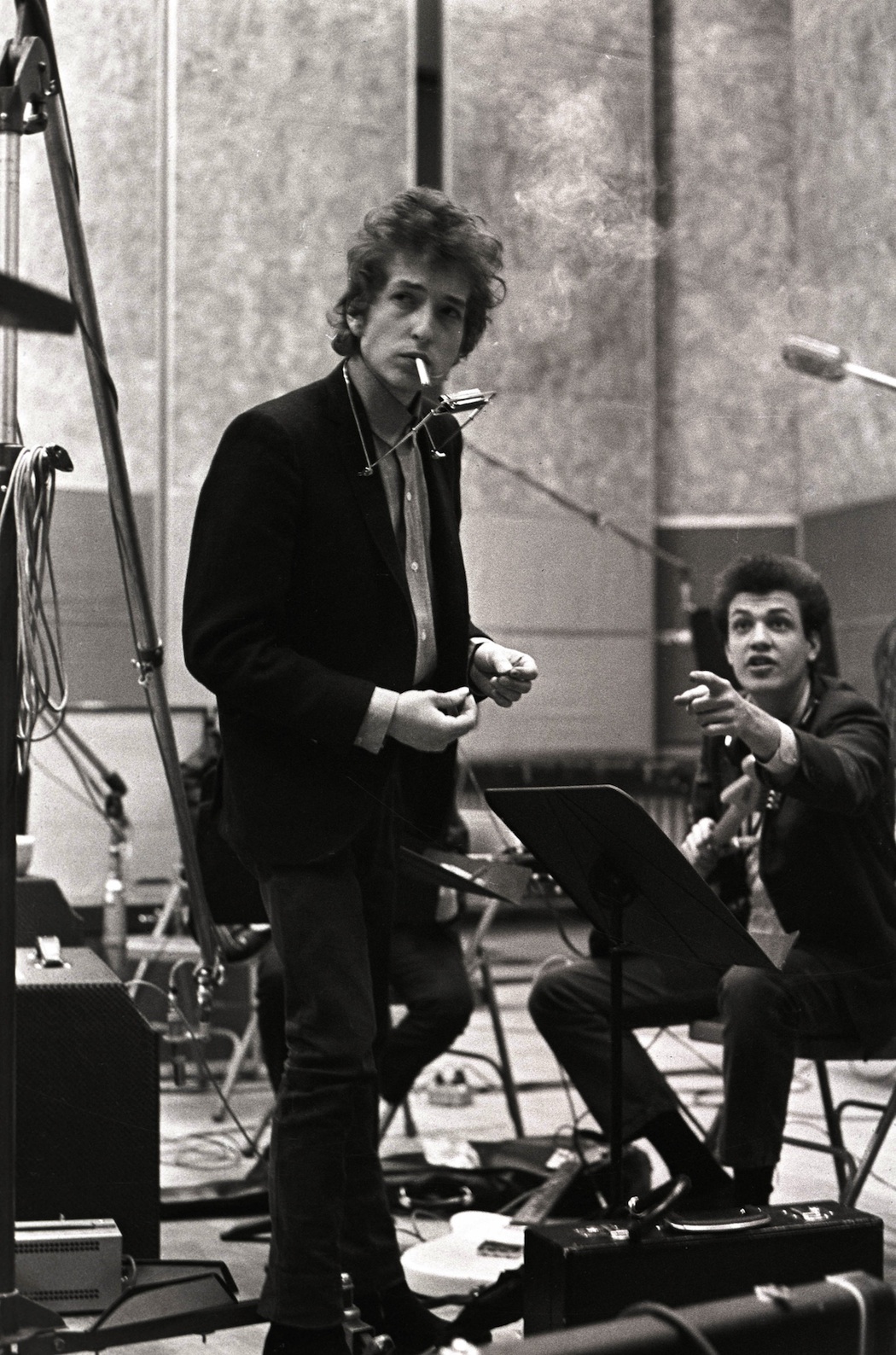

Bob Dylan and guitarist Michael Bloomfield at the sessions for “Like a Rolling Stone.” Courtesy WBUR

He is banging the gong of the rhythm as if he is hypnotized by it, each glorious note bending back toward the one before it. As the band seemed to play more slowly as if recognizing the story in the song for the first time – a congress of delegates drawn from all over the land, all speaking at once and all giving a version of the same speech – the singer moves faster, as if he knows what’s coming and has to stop it. He reaches the last line of the verse, holds the last word as long as he can hold his breath, and then as the song tips into the third chorus everything shatters.

The intensity of the first words out of Dylan’s mouth make it seem as if a pause has preceded them, as if he has gathered up every bit of energy in his being and concentrated on a single spot, it is as if you can hear him draw that breath. “How does it feel” doesn’t come out of his mouth; each word explodes in it. And here you understand what Dylan meant when he said, in 1966, speaking of the pages of noise he’d scribbled, “I had never thought of it as a song, until one day I was at the piano, and on the paper it was singing, ‘how does it feel?'” Dylan may sing the verses; the chorus sings him.

With this moment every element in the song doubles in size. It doubles in weight. There is twice as much song as there was before. An avenger the first time, “how does it feel” takes them over here, the second time the line sounds Dylan is despairing, bereft and sorrowful, but by now, moments after he himself has blown the song to pieces, the song has gotten away from him. Kooper’s simple, straight, elegant lines are breaking up, shooting out in all directions, as if Dylan’s first “how does it feel” was the song’s Big Bang and Kooper is determined to catch every fragment of the song as it flies away.

As the chorus begins to climb a mountain that wasn’t in the chorus before, Kooper finds himself in the year before, in the middle of Allan Price’s organ solo in the Animals’ “House of the Rising Sun,” a record that to this day has lost none of its grime and none of its grandeur. Price’s solo was frenzied, its tones thick and dark; it was a deep dive into a whirlpool Price himself had made, and Kooper is playing from inside the vortex, each line rushing up and out, nailing the flag of the song to its mast. 1

Nothing could follow this. In the fourth verse, everyone’s timing is gone. The “Ah” that that swung the first line of the third verse is here a long “Ahhhhh,” that flattens its own first-line. Bobby Gregg, whose drum patterns in the first verse had given the song shape before the musicians found the shape within the song, fumbles as if he has accidentally kicked over his kit. Everyone is fighting to get the song back – and it’s the words that rescue it, that for the first time take the song away from its sound. The words are slogans, but they are arresting, and if “when you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose” sounds like something you might read on a Greenwich Village sampler, a bohemian version of “Home Sweet Home,” “you’re invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal” is not obvious, it is confusing.

Confused – and justified, exultant, free from history with a world to win – is exactly where the song means to leave you. There is the last chorus, like the last verse spinning off of its axis, and then Dylan’s dive for his harmonica, and then a crazy-quilt of high notes that light out for the territory the song itself has opened up.”

****

Marcus leaves us (for now) with a closing image alluding to perhaps the most apt of the great American myth-odysseys for this song, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which follows Dylan’s artistic voice much more closely than does Fitzgerald’s romantic Gatsby or the almost Titanic might of Melville’s grapple with the white whale.

Still we feel somewhat breathless for having rode his words through the churning bile of “Rolling Stone.”

Where do we go from here? Forty years down the road, no one can say for sure, except perhaps the mystery tramp, who’s not selling any alibis. So you’re on your own, the road does seem to go on forever, if it hasn’t for as long as you can remember, since the fateful day in 1966 when you heard the song for the first time, and everything changed.

_______

1 Here Marcus makes two powerful references, in quick succession, building his momentum. However I take issue with one. Kooper’s descending organ riff throughout is majestic and he rides the song’s drive and passion, but he never becomes the unsuspecting protagonist, as does Price in his “House” solo, a man hell-bound for the depravity and fleeting ecstasy of a bordello. But but I concur with the writer’s deft allusion to the closing scene of Melville’s Moby-Dick, (explained shortly in the ensuing text) and the strange, seemingly impossible sight of harpoonist Tashtego nailing a banner to the mast as his hammering hand succumbs to the roiling waves engulfing the entire ship. Certainly the accumulating power of “Rolling Stone” swims in the same turbulent ocean, by now.