Jack Grassel playing his triple-neck guitar-bass-mandolin at Villa Terrace in a solo performance Sunday morning. Photos of Jack here and below by Mi/Jo, courtesy Jill Jensen.

I had a Saturday night-Sunday morning dilemma that country singers mournfully ponder, but it wasn’t about making up for excess, rather, if anything, neglect.

Saturday night I finished watching Peter Jackson’s wonderfully fascinating and moving three-part Beatles documentary Get Back. It reveals the world’s greatest pop music band in all their genius, idiosyncrasy and humanity. But everybody and their cousin has written and opined about that, which is worth all the praise it has received.1

Sunday morning I did not go to church, rather I attended a solo concert by Racine guitarist and multi-instrumentalist Jack Grassel, a Wisconsin guitar god if we have one at all. 2 I suppose I could be accused of paganism because the dominant symbol of the event was the ancient, larger-than-life statue of Mercury, the Greek messenger of the gods, son of Zeus. But perhaps no other concert setting in Milwaukee possesses more radiant overtones of spiritual power commingling with serene aesthetic magnificence than Villa Terrace, Milwaukee’s own little corner of Renaissance Italy. The sculpture itself is a masterpiece of contrapposto, composed yet coiled. (see photos below, and at bottom).

Last Sunday morning, musical shape-shifter Jack Grassel situated himself in the archway directly aligned with the ancient statue of Mercury. Photo of the courtyard courtesy Villa Terrace.

Ah, but Mercury was known as a trickster, even with the other gods, what we might call today a shape-shifter.

As Jack Grassel was aligned directly behind Mercury – yet apparently visible to every listener from their courtyard vantage points – some symbolic affinity connected Jack and Mercury. For as long as I’ve known Jack, for multiple decades, he’s been something of a musical magician. But I have never seen him more of a trickster-shape-shifter than he was Sunday morning 3

He took us on a wobbling and bounding tightrope walk across the tensions between the creative artist and the public purveyor of said goods, or talents. Or, as he put it in an e-mail afterwards: “For years I’ve been chasing the carrot. Sunday, I actually caught it for the first time ever. Now I intend to hang on to it.”

That implies that he succeeded is his quest Sunday, on his own terms as they relate to engaging the audience in his perhaps-unprecedentedly entertaining shape-shifting (more on this shortly).

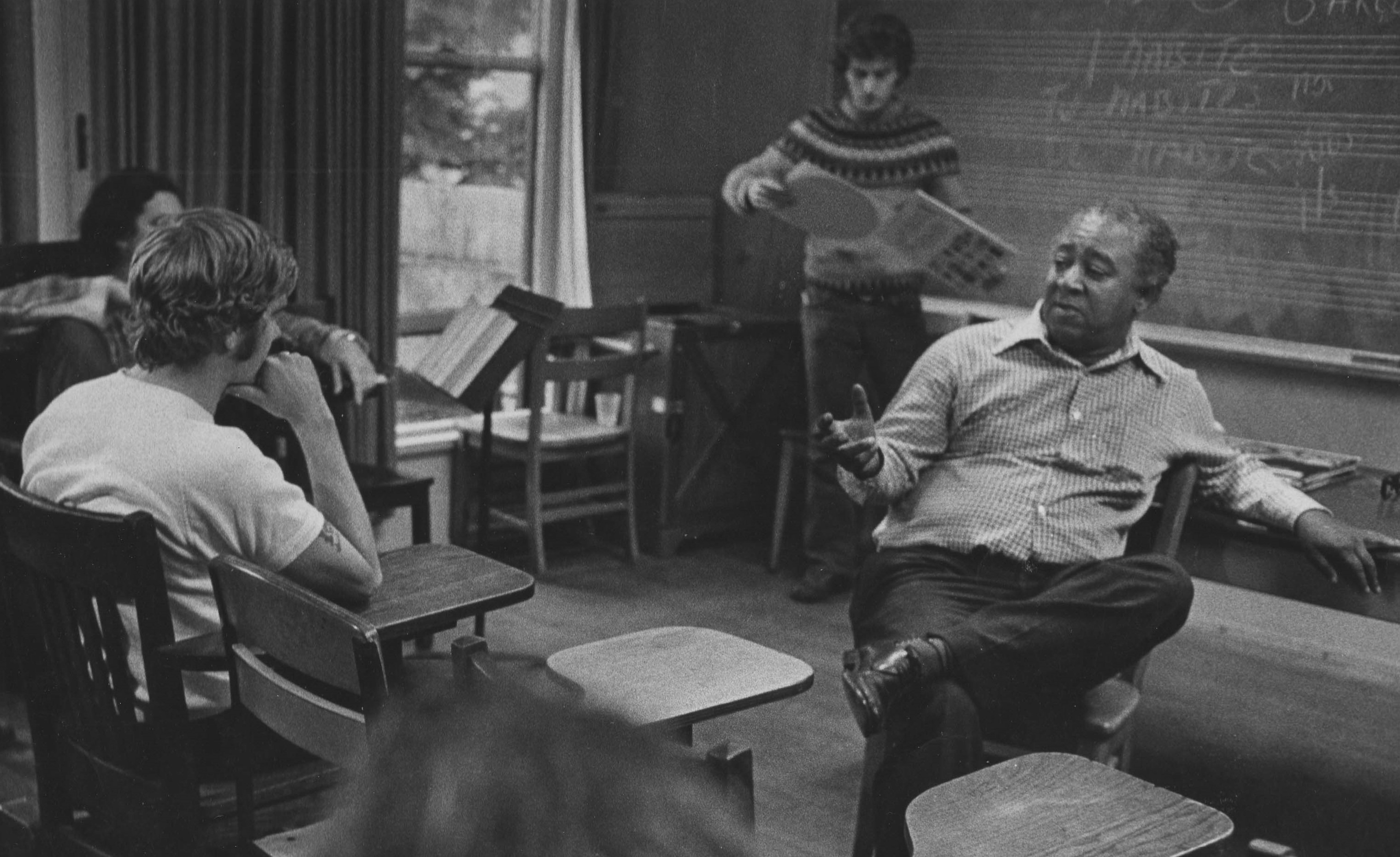

Part of my motivation for this blog post is not having appreciated Jack “in print” with any critical depth in recent years, although I have written about him years ago (and in my forthcoming book) when he was with the innovative Milwaukee jazz group What On Earth? He launched his solo career in earnest during the 20 years I spent in Madison, and in recent years I have considered him a friend as much as a critical subject. This, of course, doesn’t do the artist justice.

After the concert, I walked up to him and offered him high praise in indirect syntax. “I’ve been thinking hard about the best solo concert I’ve ever heard, and I really can’t think of a better one,” I said. Jack gave me a slightly quizzical smile. Now, upon reflection, I realize it was overpraise to a degree, and maybe Jack knew that immediately.

After all, he and I drove all the way to wintry Toronto in 1977 (with drummer Dave Ruetz, another member of What on Earth?), to hear Cecil Taylor, the Olympian jazz pianist. There Taylor performed two three-hour solo piano concerts, through afternoon and early evening. As Jack might concur, Taylor’s remains the greatest solo performance I’ve ever heard, though recitals by classical pianists Alicia de Larrocha and Richard Goode also stand vividly in my memory. Of course, Taylor’s was “high art” in a dynamic yet almost austere sense.

Jack Grassel is quite capable of “high” musical art, which he accomplishes almost every time he performs and, indeed, more overtly when, for example, when I witnessed him courageously sit in with The McCoy Tyner Quintet at the peak of that great pianist’s powers in the mid-1980s — and pull it off.

But Sunday Grassel was attempting something different — you might call it the advanced art of musical entertainment. Some of the credit for the loosening up of his sensibility should go to his spouse and regular working musical partner, jazz vocalist Jill Jensen. She was there Sunday, working the merch table, but honoring this as Jack’s show all the way.

He situated himself comfortably in the very American tradition of carnivalesque, traveling sideshows and vaudeville – the one-man band. This shouldn’t be too surprising given his deep history as a state champion accordion player in his youth. Ever since, he’s been one of the most rigorously dedicated musicians I have ever met. As for the artist-entertainer push-pull, he’s always maintained stern standards in live performance even though he’s also consistently exhibited a ready sense of humor and musical zaniness. His jazz efforts include a wide range of recordings, including a dazzling collaboration with the great swing-to-bop guitarist Tal Farlow, an album unassumingly titled Two Guys with Guitars.

Having played with the Milwaukee Symphony a number of times, Grassel struck up an artistic connection with then-musical Musical director Lukas Foss, whom he quoted or paraphrased by saying, “all serious music has humor in it.” He set out to prove that Sunday, his tongue firmly in cheek..

Indeed, there was even some “humor” in Cecil Taylor’s 1977 performance, in the absurdity of it’s most over-the-top and improbably moments of physical assault upon the piano. At times, I laughed in amazement. By conventional standards of pianistics, this was definitely Mercurial shape-sifting, even in Taylor’s panther-like dance-move entrances and exits.

As to Jack’s mission today, Jill Jensen makes an important distinction, as they often perform fairly obscure material across a wide range of styles: “We’re not doing crowd pleasers. We’re trying to be the crowd pleaser,” she says.

How did Jack please the crowd Sunday?

- He played Elvis Presley’s “Blue Suede Shoes,” but stylistically as if blues giant Muddy Waters would’ve done it. So Presley’s proto-hip-hopping rhythms turned dolorous and dark, as if a slightly more ominous threat, if you don’t “lay offa mah blue suede shoes!”

- He played an abbreviated version of the slow movement of Rodrigo’s gorgeous Concierto de Aranjuez, made famous by trumpeter Miles Davis and Gil Evans on the album Sketches of Spain. This made sense in that the piece is originally a guitar concerto. Grassel even pulled out a harmonica, which somewhat evoked Davis’s poignantly eloquent trumpeting, but without mimicry. This did surprising justice as a solo performance of a piece best known as a concerto with a full jazz orchestra.

- He sang jazz singer-songwriter-pianist Mose Allison’s “Certified Senior Citizen,” which includes: I’m a certified senior citizen

‘Scuse me while I take my nap

You don’t like my drivin’, I don’t like your jivin’

Just don’t give me that ole timer crap He did this not to suggest the audience was old-timers, but because, as he explained, he now was “certified” himself. - He also credibly sang Sting’s “Sister Moon” in a high baritone approximating that singer-songwriter’s register, though without the resonant romanticism of Sting’s voice.

- A one point, he even sat down and played a home-made drum set which includes a donging cast-aluminum pot lid from Jill’s kitchen. He evidently practices at home with typical zeal on drums, about which Jill afterwards commented dryly “is grounds…” The second time he sat down at the set, he pre-empted sentiments by saying, “Oh no, not the drums!”

Throughout, Grassel, complemented his artful juggling of his self-designed, triple-necked guitar-bass-mandolin with deft electronic keyboard playing, which also set up looped rhythmic patterns he would play against on other instruments. I hope you begin to sense Grassel’s wizardly and mercurial shape shifting, which certainly would’ve impressed PT Barnum, while maintaining Grassel’s own standards of musicality and wit.

That, however, included a solemn interlude in which Grassel requested the audience not applaud afterwards. He played his own composition “Ghost Ridge,” set against indigenous-style rhythms, on a Native American wooden flute, to honor victims of a genocidal massacre. His playing met the passing winds and invited them to caress the Indian mounds and righteous memory.

By contrast, the extraordinary concert ended on a note so light that the piece’s notes literally floated away. Grassel picked up a bright yellow toy saxophone and, when he started playing, bubbles floated out of the horn’s bell, evoking perhaps for some of the “certified” senior citizens, the bubbling visual effect of Lawrence Welk, in perhaps slightly satirical manner.

Grassel may think he’s only just now “grabbed the carrot,” but you need to go back to 1986 to note when he started making a successful impression at a national level. That was the year his breakout album Magic Cereal, gained both some critical and commercial appeal, making it onto jazz radio station playlists, as far as the market went for such meaty but ingeniously snappy fusion jazz. Magic Cereal managed to vibe both weird and engagingly friendly, with sophisticated electro-sonics but street-right rhythms. His chord changes may sometimes lean sideways into the wind, but he always sustains his floating aura, like a magician rising right out of your morning Cheerios, which might transform into bubbles.

Grassel’s been a successful working musician ever since, even after nearly dying from a respiratory condition contracted while working at Milwaukee Area Technical College, which forced him to retire from classroom teaching.

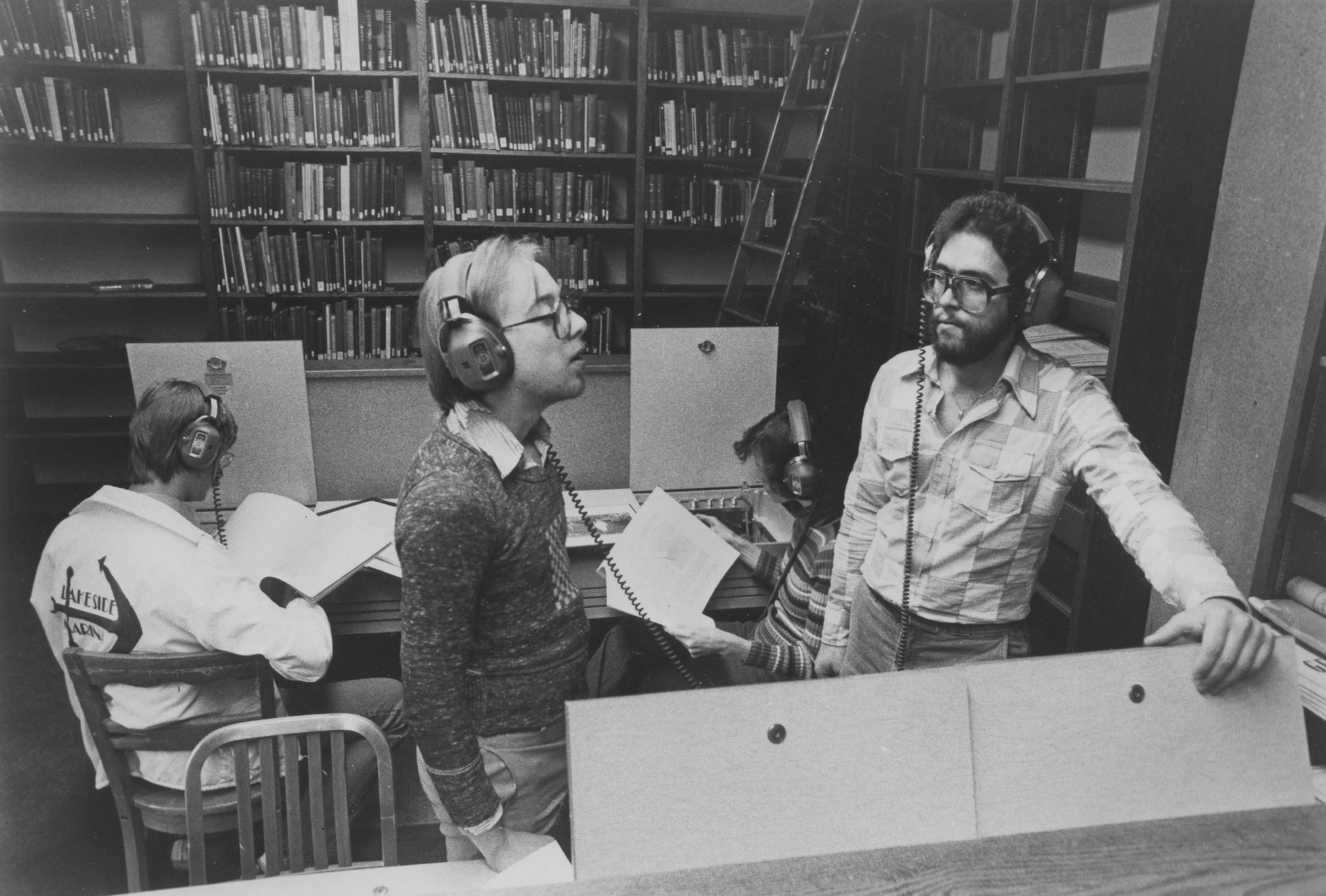

Nowadays his sets with singer Jill Jensen range from Mose Allison through James Taylor, and Sade through “Besame Mucho.” “The lines between genres are really blurring,” Grassel says. Jensen recalls another remark from an audience member. “‘What do you call what you’re doing? I really like it!’” By way of explanation, she says, “We’re still under the umbrella of jazz but we massage the songs to sound like us.”

Sunday, Grassel stretched and massaged that umbrella until it encompassed the attendant Greek god himself and his uncannily mercurial powers, for at least an hour and a half.

Jack Grassel and Jill Jensen will perform from 7 to 9 p.m. Friday, Aug. 26, at Sam’s Place Jazz Cafe, 3338 N. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Dr., in Milwaukee.

“We will play a nonstop 2-hour set of adventurous material,” Grassel promises.

_______________

_______________

1 Aside from the three-disc film video Get Back, which retails for $34.99, the best version of the album the group was trying to make is Let It Be…Naked, rather than the re-issue of the original Let It Be album, with lots of outtakes. The group’s explicitly stated purpose throughout the several weeks of preparing for a recorded concert was to do a “live album,” whether before an audience in the studio without any overdubbing, such as the souped-up strings of Phil Spector, on the original release, which Paul McCartney hated. Let It Be…Naked is the unadorned, rather rootsy album as it should have been, which is a mix of live performances from their heart-rending and impassioned last public performance atop the windswept Apple studios in downtown London (which nearly got them arrested), and “live” studio renditions.

2. Now that Les Paul is gone, I suppose it’s a toss-up for resident “Wisconsin guitar god” between Grassel and Greg Koch, who was much more visible, even through the pandemic (unlike Grassel), with regular You Tube video performances.

3. Bobby Tanzilo, “Restoring Villa Terrace’s Hermes/Mercury Statue,” Milwaukee.com.

Repair of the statue is reportedly at the top of the current villa administration’s “to do” list after having been severely damaged by Wisconsin weather over the years.

“The nearly 8-foot-tall, two-ton statue of Hermes – aka Mercury, messenger of the gods, son of Zeus – that has graced the arcaded courtyard of Villa Terrace, 2220 N. Terrace Ave., since the museum opened, is believed to date to the first or second century A.D. and has parts that may be even older”… Restored in the 17th century – reportedly by master Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, though without definitive attribution (it may have also been the work of Francois Duquesnoy) – the statue is believed to have been purchased in Italy by American collector Mary Clark Thompson.” https://onmilwaukee.com/articles/villa-terrace-hermes-mercury

The Villa Terrace Art Museum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Photo by Kevin J. Miyazaki