The Middle Teton’s summit in winter of 2014, but probably similar to what it looked like when Harry Frishman climbed it in January of 1981. Courtesy splitdecisionsdotorg.wordpress.com

I recall Harry Frishman, for all his courage, as a man of almost Zen-like serenity. In the summer of 1980, he expertly guided his son Cullen, Mike Pellman and me up a climb that was the climax of my mountaineering experience. He instilled confidence in me with his forthright but calm demeanor. We were attempting to climb Peregrine’s Arete, only the third-party to ever tackle this peak in the Tetons. Because the great mountaineer Yvon Chouinard had discovered the peak not long beforehand, we had no very detailed information on the climb route. Harry, an Exum mountain service guide, had never seen this rock before

“We may just end up doing a first climb ourselves,” Harry said at the time, stuffing the rough directions he’d received from Chouinard back that his pocket. He began climbing with a graceful poise (story continued below).

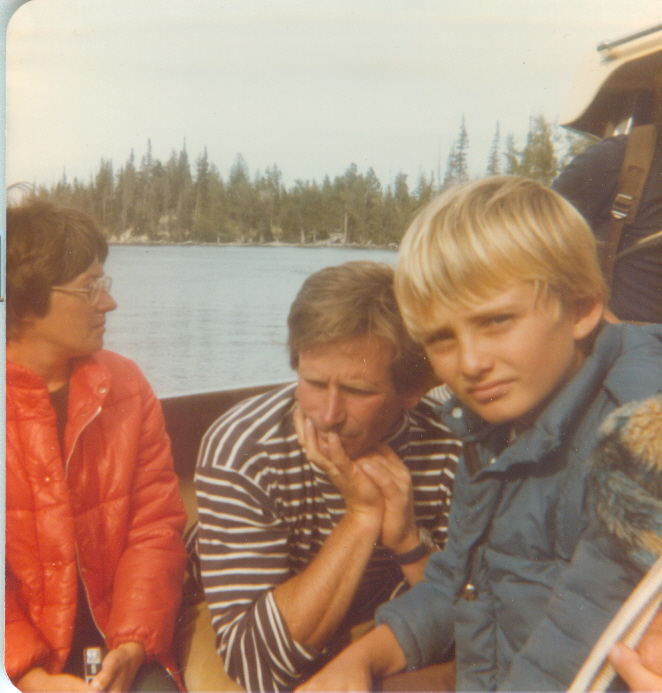

Exum climbing guide Harry Frishman muses quietly as we ride a boat across Jenny Lake to encounter rarely-climbed Peregrine’s Arete in the Tetons, in the summer of 1980. Perhaps he was contemplating the tragic climb in Nepal he was planning for three weeks later.

Guide Harry Frishman, right, and his teenage son Cullen pause atop the summit of Peregrine’s Arete.

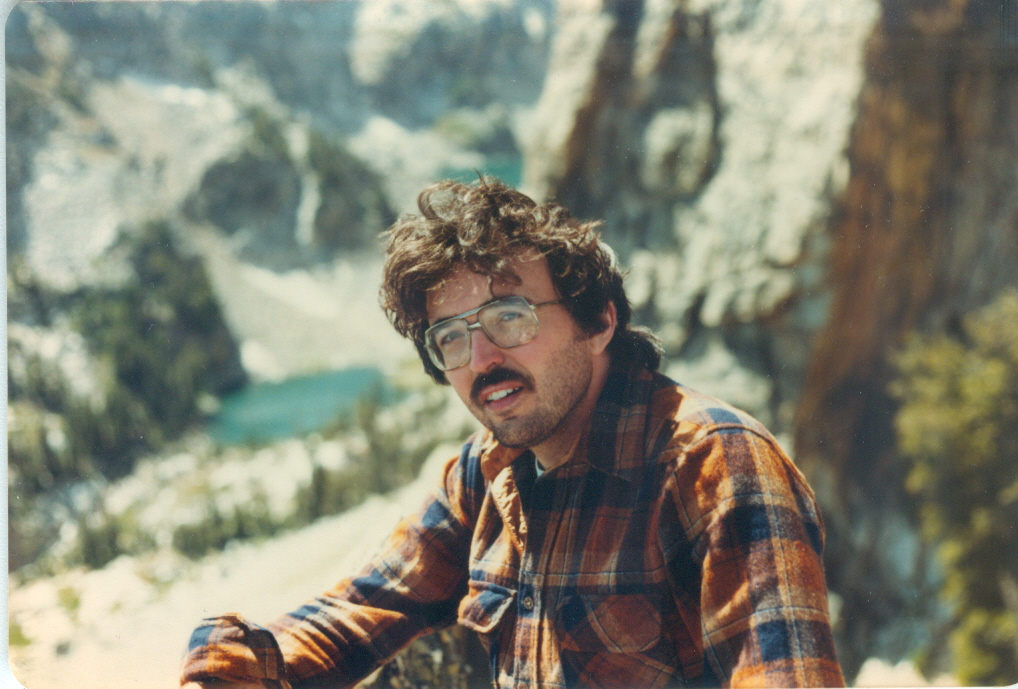

Your disheveled blogger, Kevernacular, struggles to gather his wits atop Peregrine’s Arete, after two nasty falls which left him dangling over eternity at the end of a rope.

Natural foods store owner Mike Pellman was Harry Frishman’s other client on our climb in the summer of 1980. Here’s happy Mike on the summit. Photo by Kevin Lynch.

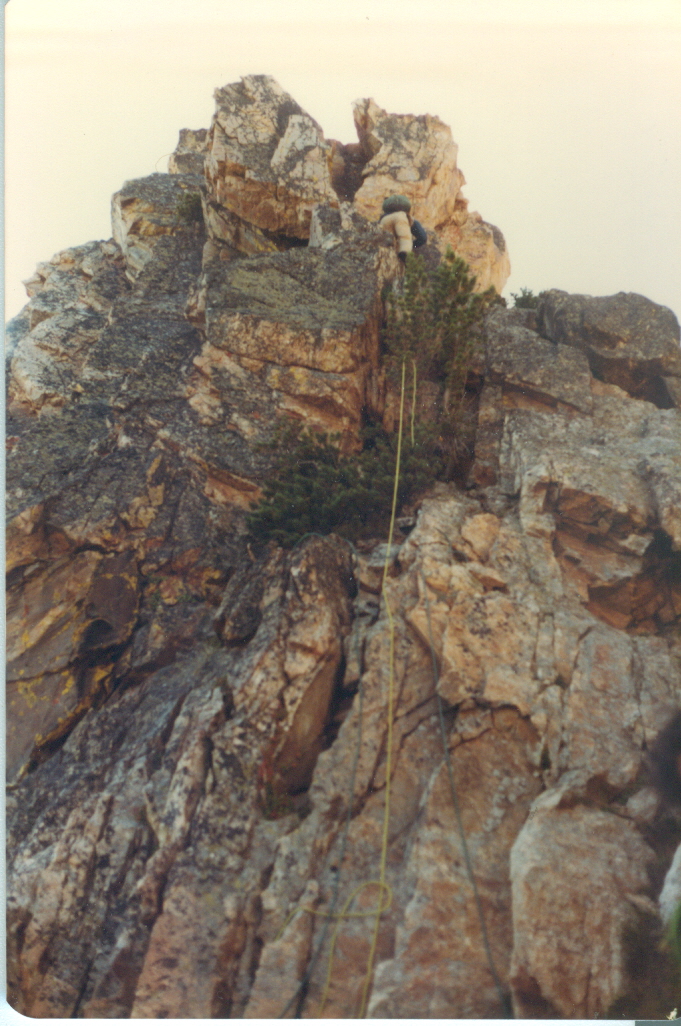

Peregrine’s Arete, in the foreground, isn’t as majestic as some of the taller Teton peaks, but it was the most difficult climbing challenge of my life.

Here’s guide Harry Frishman at the top of a pitch on Peregrine’s Arete. The climb provided some excellent views, on the left is Hanging Canyon from the Arete, and on the right is a view of the ground of Grand Teton National Park, far below.

The climb provided some excellent views, on the left is Hanging Canyon from the Arete, and on the right is a view of the ground of Grand Teton National Park, far below.

It was a memorable and really tough climb on which I took two nasty falls on the same pitch, a long vertical crack which is visible in the photo of the arete above. Something flashed before my eyes as I fell my death, unsurprisingly, but no one else. I recall saying out loud to myself and the mountain later, as we descended, “I’m thirty years old, I’m too old to be climbing this mountain!” I fully recount the climb in a long feature article I wrote about it for The Milwaukee Journal Discover section. You can access the full article below.

But why do I bring this up at this point in time? It certainly was a sort of happenstance, but I had to tell the story.

I had recently asked my girlfriend Ann Peterson if I had ever shown her the Journal article and she told me she had read it a few years ago, but she was disappointed because she never knew what happened to my guide Harry Frishman.

At the end of my Journal article I wrote an epilogue. Three weeks after our climb of Peregrine’s Arete, Frishman traveled to Chinese Nepal to climb 24,790-foot Mount Minya Konka, with Yvon Chouinard and several other climbers. An avalanche swept the climbers 1,500 feet down the mountainside. One of the climbers died of a broken neck.

But this was before the Internet, so I was unable to get further information about the climb at the time.

Yet now, Ann’s comment about Harry’s fate spurred me to Google his name recently. Sure enough, he had survived the avalanche in China. But I found an article about a climb he did in January of 1981, on The Middle Teton, back in Wyoming.

The Middle Teton is the third tallest peak in The Tetons. A distinctive feature known as the black dike appears as a straight line running from near the top of the mountain down 800 feet.[6] (See photo below) The black dike is a basaltic intrusion that occurred long after the surrounding rock was formed.[5]

Here’s the Middle Teton in August in the mid-1970s. Note the large face, one of the most imposing in North America, and the distinctive black dike on the face. Photo by Kevin Lynch

Here’s the Middle Teton in August in the mid-1970s. Note the large face, one of the most imposing in North America, and the distinctive black dike on the face. Photo by Kevin Lynch

This peak poses a special challenge, even to the most skilled and experienced climbers, like Harry and his companion, Mark Whitten. They decided to climb the Northwest Ice Couloir. The story gave me chills in more ways than one. I had always been intrigued by ice climbing but had never gotten around to doing it. The challenge, different from rock climbing, is that your body grapples not only with gravity but the vagaries of frozen water as a climbing surface.

In the story I discovered, Craig Patterson, a Grand Teton National Park Ranger, interviewed Mark Whitten after the climb. Patterson recounts:

“This route is described in Leigh Ortenburger’s A Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range as ‘a difficult high-angle snow and ice climb.’ It is rated at Grade II, F6. Both Frishman and Whitten had extensive mountaineering experience. That morning they left the Lower Saddle and began ascending the Northwest Couloir. They decided to climb unroped, although they carried a rope with them. They also had crampons and ice-climbing tools but no hard hats.

The Northwest Ice Couloir of The Middle Teton, where Harry Frishman and Mark Whitten climbed, without ropes, in January 1981. This photo shows a lead climber — a belay from below secures him, relatively speaking. Photo courtesy www.mountainproject.com

Around 11:15 a.m. on January 19, Whitten successfully reached the top of the couloir, with Frishman close behind. A few feet from the top, Frishman slipped. He was unable to self-arrest on the steep ice and fell approximately 2,000 feet to his death. Whitten was unable to reach Frishman, so he ran out to the Moose Visitor Center for help.”

Reading the story, I felt the wind knocked out of me. My eyes welled up a bit. Harry Frisman had always remained a vivid memory, a quiet but gracious man.

(Here’s a link to Patterson’s story, including more details about Harry’s fall: Middle Teton ice climb )

I’ve read that Harry was also a big practical joker. So you can rarely capture a person with one charcterization, such as the uncanny calm I sensed in him as he led us up our climb, two years earlier.

Fate had played a practical joke on Harry, the biggest joke of all, bigger than any mountain he had ever climbed. Our Peregrine’s Arete climb was graded an F6, like the Middle Teton, maybe a F7, Harry had speculated at the time. But that was in late summer. I wonder now why the two climbers decided not to use their ropes and belay up on the icy, treacherous coilour. Harry was 38, older than the 20-year-olds who typically feel invincible. He was also father and a husband. But his was the climber’s life and its awful, inevitable risk.

He had survived a far more ominous climb and avalanche in Nepal. So maybe he felt he had the upper hand on fate as as he came a few steps away from the Middle Teton summit that cold January day.

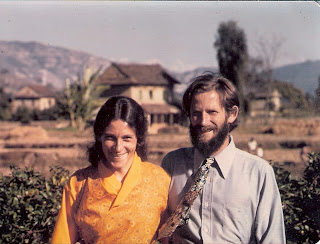

Harry Frishman and his bride Libby, also a climber, when they married in Kathmandu, Nepal in 1972. Photo courtesy http://stephenbodio.blogspot.com

____________________

Photos by Mike Pellman, unless otherwise indicated.

Here’s my article about the Peregrine’s Arete climb with Harry Frishman in 1980:

Harry Dean Frishman’s gravestone in Wilson, Wyoming cemetery says that he died on January 19, 1981. If so, he couldn’t have been climbing in 1982 as the article states. Also, at the base of his headstone is carved the phrase “Goddamn a potato.” I know the phrase is from Chief Washakie talking about the native homeland being divided up for farming, but why is is non Harry Dean Frishaman’s gravestone?

Dale, Thank you very much for your information about Harry’s death date. I have made the appropriate corrections in my blog post. I apparently got the 1982 date from the date of the publication of the article I referenced as my source for his death — my mistake. The actual date impacts my memory of him even more, as he died less than six months after my climb with him, also in the Tetons.

I do hope you found some of the blog of interest. As for Chief Washakie’s phrase, I don’t know why it is on Harry’s gravestone. But I can speculate that Harry was extremely sympathetic to the plight and viewpoint of Native Americans and their native homeland. He clearly valued the pristine, unspoiled and unravaged natural terrain and mountains of America. Thus, the phrase would have a deep cultural resonance with his spirit.

Thanks for commenting,

Kevin Lynch

Kevin, thanks for responding. I am glad for your response about the epitaph. I was thinking maybe it was more of his practical joking, like handing out “Sex, drugs, and rock and roll” badges to the natives in China. I like the reverence for Native American idea better. I was able to speak with Ted Wilson last week. He was a former Exum Guide in the Tetons and former mayor of Salt Lake City. He was featured in a pbs film about a big rescue on the Grand Teton in 1967. I waited around after his talk and presentation, showed him the photo of Harry Dean Frishman’s headstone. He said he knew Harry well and knew exactly where on the mountain he fell. (I had printed out your blog and the article you had a link to. It didn’t seem the right time to bring it up. I know his daughter, so maybe I will pass the printouts on to him via her.) But he didn’t know about the phrase on the headstone. So they mystery goes on. But your answer sounds right and appropriate, I will send you a photo I took in the 1980s of his headstone in the Elliott Cemetery in Wilson. By the way, I found out today that a descendant of Nick Wilson who started the first white man settlement—the beginning of the reason for Chief Washakie’s lament— in Jackson Hole, works at my company. Chief Washaskie, though kidnapped Nick Wilson as a young boy and raised him as an Indian for several years and introduced him to Jackson Hole, so he can’t be too mad. I have to meet him still. If you have an email address, I can send you the photo, or you can go to findagrave.com or one of those sites and find it there.

Don’t know if all that made sense, but don’t know how else to explain it. I am sure Harry Dean is glad that you kept his memory alive and that we are still talking about him over 30 years since his death. Thank you.

Dale my email address is daleboman@mac.com

Dale,

Thanks for the great historical background and for sharing your interaction with, and the thoughts of, Mayor Ted Wilson. I will search out the PBS film involving him and the big 1967 rescue on the Grand. If you do share my article with him, let me know his response. BTW, I recently saw the excellent film Wind River, set in Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation. Though it’s not in the Tetons, I’m sure Ted Wilson knows the reservation and probably the true story behind the film — of the Native American woman raped and murdered by drunken white men. It’s a tribute to the countless similarly-killed (and most likely unknown and unaccounted for) Native American women who form part of the deep human backdrop of the #MeToo movement. I’m sure Harry Dean Fishman would’ve approved of this austerly beautiful movie as well. — Kevin