John Steuart Curry’s “Wisconsin Farm Scene,” oil on canvas, 97 by 89 inches, 1941. Lent by The Chazen Museum of Art, Madison.

John Steuart Curry’s relationship with his native state of Kansas was as troubled as a convulsing tornado, and the raging soul of John Brown. Curry became famous when he gave that state indelible public images.

His paintings of their swirling escalators to Oz and the anarchistic, slave-liberating Brown, and of fundamentalist baptismal dousings in a wood barrel, embarrassed early Kansas critics likely hoping his fame might help boost the state’s nation image in the newly modern and chic 1920s.

But Curry painted “the American scene,” with the same rough-hewn, real-life observational sensibility of Thomas Hart Benton and more craftsman-like Grant Wood. They would become renowned as the three major Midwestern regionalist artists, comparable to another new American storytelling art form, the more urban “Ash Can School” artists, who preceded them by a decade or so.

While Kansas worried about flying witches and other cultural blights, Wisconsin and in its visionary Big Ten university lay poised, deep in its rolling hills and forests, to woo the man to help artistically express its ideals, a man who created a new art largely independent of modern European influences.

Wisconsin made all the right moves, as is evident in the artwork and underlying story of John Steuart Curry at Home in Wisconsin, the new exhibit at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend, which is running through September 14.

This show title is slyly docile, domestic as a curled-up cat. But more’s afoot at this ambitious flagship for Wisconsin art. MOWA made a good move itself, when it re-defined part of its mission to exhibit not only native Wisconsinite artists like photographer Edward L. Curtis, but also artists, like Curry, who “lived in the state for a period of time and had a transformative experience here,” as MOWA executive director Laurie Winter explains.

An impressive show in Madison at the Elvehjem Museum of Art (now, The Chazen Museum) in 1998 traced Curry’s impact in defining the Midwest from the standpoint of the era’s natural and societal turmoil. The MOWA exhibit provides Wisconsinites with a fuller sense of a crucial if more internal story – of outreach-style rural education and collective state-side war efforts. But the cumuli-graced air he painted was also sometimes filled with UW flying footballs and a big buzzing vibration called “The Wisconsin Idea”, which helped the painter transform into a state citizen and ambassador for his adopted state in the progressive sense the idea espoused.

In November 1936, Curry was the first artist featured in the new LIFE magazine which would help “America’s foremost painter of cyclones and circuses” move squarely in the middle of American consciousness.

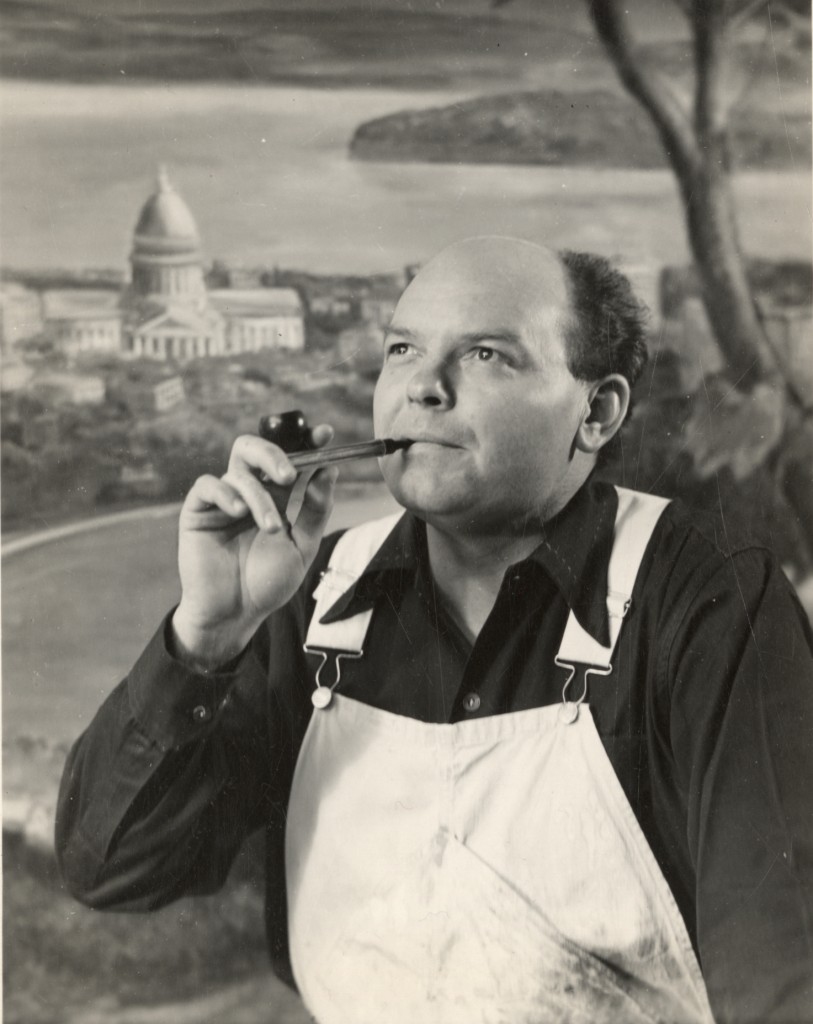

Curry, the nation’s first artist-in-residence at a university, poses in front of “Madison Landscape,” a painting familiar to Madisonians for having hung previously in The Madison Civic Center lobby, and currently part of the collection of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art. 1941 photograph courtesy of UW Archives.

Wisconsin’s savvy talent scout was Chris L. Christiansen, Dean of the College of Agriculture, who lured Curry to Wisconsin in a telegram on display here, and hired him for $4,000 a year as the nation’s first “artist in residence’ at a university. By then, fame had virtually compelled Curry to move to the East Coast, but he was never comfortable in the high modernist climate there, and he longed to return to the Midwest. Unsurprisingly, Kansas sent no zephyr whispers his way and, by 1939, the state became immortalized as the ultimate tornado state, when Dorothy murmured “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

Nor was Curry who, though possessing the least draftsman skills among the three big Regionalists, had a big-sky state vision that understood the power and meaning of the brawling and sprawling American landscape. As the often-acerbic Benton himself wrote of Curry’s famous “Wisconsin Landscape”: “(It is) a strange picture. It is at first sight slightly repellent.” But Benton’s second thought was, “this damn thing is a masterpiece of some sort.” 1 The painting, property of The Metropolitan Museum of Art and not in this show, is surely Curry’s masterpiece.

Benton sensed how Curry’s Kansas eye fell hard for Wisconsin’s far shapelier curves, and the work reflected the way UW-driven Wisconsin Idea was modernizing the farmscape, striving to bring modern technology and know-how in synchronicity with extraordinary natural resources.

MOWA curator and director of collections Graeme Reid explains that the UW’s art and art history departments were in the mix for getting Curry as their department star. But Oskar Hagen, head of the school’s department of art history and criticism, anticipated the political “bickering” that would likely ensue among the culture-vulture departments. So he let Ag have Curry, and the whole university and state ultimately benefited from his prominence.

The shy but affable Curry embraced his state ambassador role here and, like the other American scene painters, was also well attuned to symbolic resonance of their work, drawing connections “from Capitol domes to silo domes,” as Reid puts it.

“View of Madison with Rainbow,” 1937, oil on canvas, lent by the Kiechel Fine Art Collection.

This is more than simple realism; clearly something vast and even heroic radiates from the verdant potency of the three great landscapes seen at MOWA shoulder to big shoulder — “Wisconsin Farm Scene,” “Madison Landscape” and “Landscape with Grouse” — all painted in 1941, for the First National Bank as a sort of triptych. Together for the first time in decades, Reid says, they convey the sweep and grandeur of “God’s country” in the deep wheat fields and swelling hills and skies that seem to float among the tree canvases like a big-as-the-sky entity.

“Landscape with Grouse,” oil on canvas, 1941, lent by the Milwaukee Art Museum, gift of The First Wisconsin Corporation and The First Wisconsin National Bank of Madison

Curry’s technical mastery of the big landscape seems to increase with each ensuing section that he did, as if he was bringing it all slowly into focus for us. The underbellies of the clouds increasingly glow golden, reflecting the sun-drenched wheat and haystacks below. He illustrates how the UW Ag department has taught area farmers to till across the grain of a hill to minimize runoff erosion which, in rainy growing seasons, steadily produced a sort of inversion of the biblical Red Sea flood, dispersing valuable fields into decimated catastrophe which contributed to the 1930s Dust Bowl.

And Curry’s fairly breathtaking view of Madison shows the capital city, a virtual “city on a hill” as New England Puritan pioneer John Winthrop once idealized, on its verdant isthmus. The the rainbow and cathedral-like clouds seem like the rising revelations of a new way of living, working and thinking about the relationship between a forward-looking government and university and an increasingly educated citizenry — courageous European immigrants and their offspring — and the state’s vast natural resources and industry. The Wisconsin Idea gestating.

Curry painted a somewhat aggrandized portrait of an iconic Wisconsin farmer in “Our Good Earth” in 1941, as part of Wisconsin’s World War II-era public relations effort. Lent by the Chazen Museum of Art, UW-Madison, College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, gift of US Treasury Department.

Then, when Curry zoomed in from his sky view his gift for symbolic image gave the state a full makeover that proved iconic with the majestic “Our Good Earth.” A photograph of Curry painting it reveals his model as a gawky hayseed farmer whom Curry transformed into a square-jawed, musclebound symbol of America’s impervious sense of “manifest destiny” which, in 1941, signified a defiance of the fascist Axis of the world war. But here and in other works Curry’s palette renders his humans as at one with the landscape and environment. The golden-hued children in “Our Good Earth” seem almost like rootsy cherubs growing right out the soil.

The notion is akin to the ideals of human and environmental harmony espoused by other progressive Wisconsin cultural leaders of Curry’s era, like architect Frank Lloyd Wright and naturalist and environmentalist philosopher Aldo Leopold, who was also a pioneer at The UW-Madison in conservation and forestry.

“What is the meaning of John Steuart Curry, Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood?” Leopold once wrote. “They are showing us drama in the red barn, the stark silo, the team heaving over the hill, the country store, black against the sunset. All I’m saying is that there is also drama in every bush, if you can see it. When enough men know this…we shall then have no need of the word conservation, for we shall have the thing itself.” 2

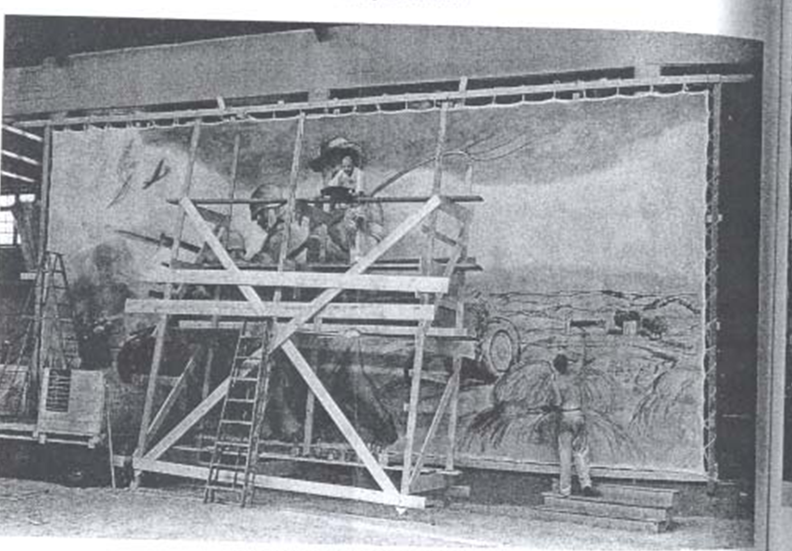

John Steuart Curry (at the top of the scaffolding) and an assistant work on his 1942 mural “Wisconsin Agriculture Leads to Victory.” The mural is not in the MOWA exhibit because “it is MIA,” says curator Graeme Reid. Its whereabouts has been unknown for a number of years.

Indeed, Curry allegorizes the conservationist’s universal impulse in another drama, the mural “Youth Helps Rebuild a World.” A group of rural Americans march towards something an oracle-like farmer points to: the smoky haze of a desolate, bombed-out city, in the far-right portion of the mural. Yet this work from 1946 implicitly acknowledges that this political and environmental tragedy could be the Allies-bombed Dresden, or even Hiroshima, profoundly tempering whatever jingoism one might initially detect.

Curry’s sprawling (308 by 95 inches) mural “Youth Helps Rebuild a World” from 1946 conveys Wisconsin’s progressive spirit of socially-conscious activism. Lent by the collection of the Helen W. Schultz Revocable Trust.

The young woman in the mural curiously wears a skirt far shorter than 1940s fashion. UW-Madison art historian James Dennis sees a pattern in Curry’s depiction of women. This contrasted with Benton, who often sensually objectified his female subjects.

Curry’s paintings “transgressed any fixed art historical label in their woman imagery,” Dennis has written. So a young woman like this “left traditional academic forms of allegorization behind, the first requirement of (her) modern independence.”

Dennis adds that, beyond 19th-century conventions of migrating womanhood, Curry created “a contemporary ‘girl-woman’ to whom he assigned his most crucial social causes.” 3

Curry died in 1946 of a heart attack at age 49, right after finishing “Youth Helps Build a New World,” with the help of assistant Bob Hodgell, in time to see the mural’s installation at The Wisconsin State Fair.

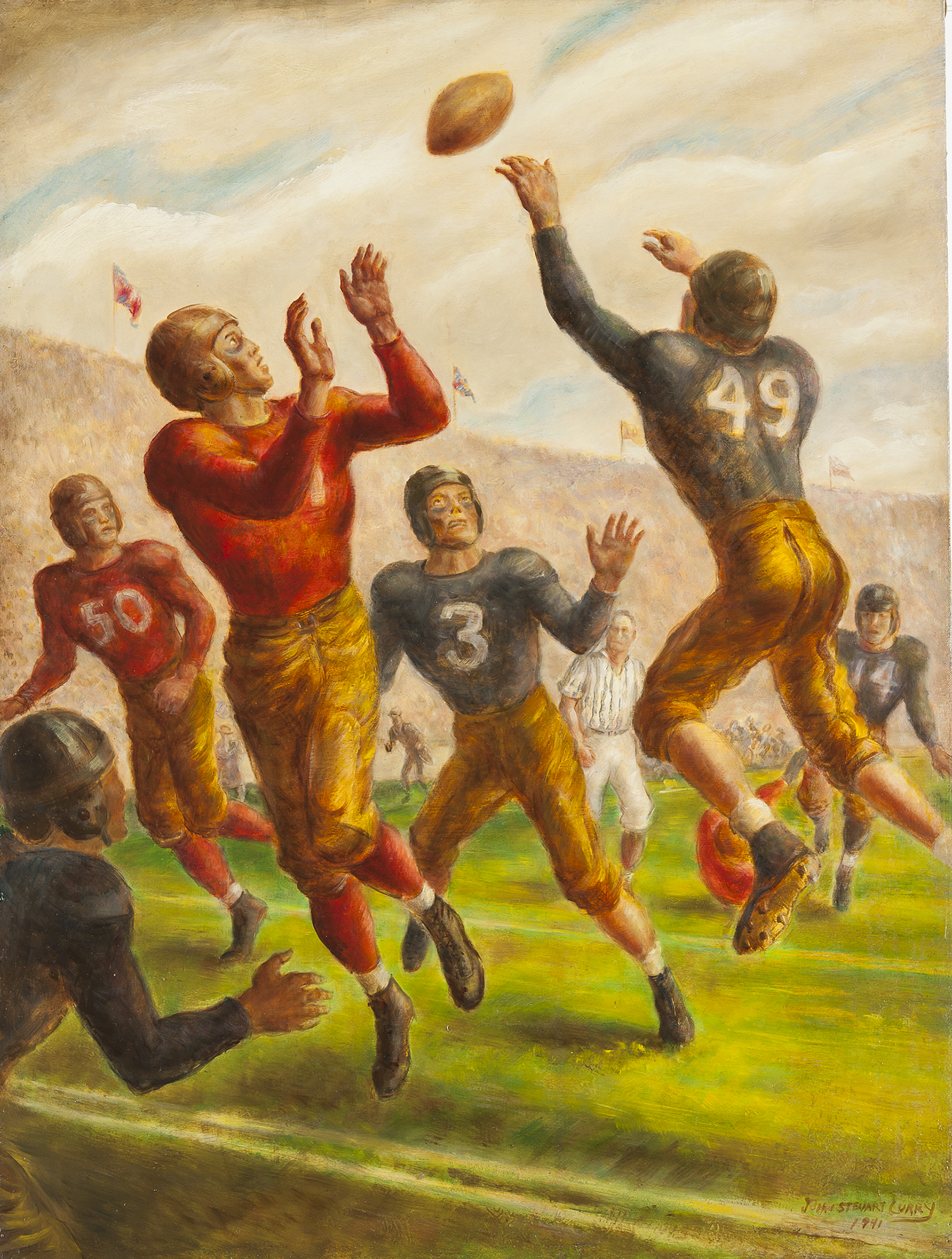

The show’s paintings and drawings of UW football action seem lighter fare, but they convey the powerful communal spirit that college football engendered. Back then, it had become much easier for the children of rural farmers and outlying city dwellers to get education from the UW, which would develop one of the nation’s leading multi-campus extension systems, a crown jewel of “The Wisconsin Idea.”

Curry, an athlete himself, exulted in the school’s sports fever. Harry Stuhldreher, one of Knute Rockne’s legendary “Four Horsemen” of Notre Dame, coached the Badgers, and the receiver catching the football in “An All-American” (1941) — is David Shriner, a two-time UW All-American who, though drafted by the Detroit Lions, would join the Marines and die fighting at Okinawa.

A large question hovers implicitly in this show: How well do the state’s current citizens, educators and political leaders live up to the ideas and ideals that forged Wisconsin’s modern identity?

One wonders what visionaries like Curry, UW Ag department’s Chris Christiansen, and Wisconsin Sen. Robert LaFollette would think of current Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s efforts to dismantle the internationally respected UW and its extension system, in the name of “freedom.” Charles Pierce, political blogger for Esquire magazine, examines Walker’s political machinations in a recent post, and re-defines The Wisconsin Idea quite well, without the bias of a Wisconsin native.

Pierce writes:

“The Wisconsin Idea was a manifestation of the creative process of making a self-governing political commonwealth that had its beginnings with the Mayflower Compact and that had been, in fits and starts, the main engine of American political and social progress for the entire life of the country. Specifically, the Wisconsin Idea was a manifestation of that process that arose in response to the vast centrifugal forces of corporate power and organized money operating within the government during the previous Gilded Age.

“The Wisconsin Idea produced improvements in agriculture and medicine through the university’s laboratories. The Wisconsin Idea produced improvements in government because it produced people like its greatest political advocate, Robert LaFollette, and his successors in Madison after LaFollette moved on to the Senate.”

4

Curry publicly embodied the creative process of the idea, which Pierce describes. In a post-modern culture morphing into a pluralist, multi-cultural, global and inter-connected world, there’s plenty of flashier, more exotic, and more cutting-edge art around, compared to Curry’s. His work, clearly is a product of its historic moment and place.

Yet the significance of the pioneering regionalist artists seems to grow in time, partly because pluralism is a fertile culture, less restrictive, and elitist, than post-modernism and much of modernism arguably was.

I’ll never forget UW-Milwaukee English Professor Ihab Hassan, the great literary critic who helped define post-modernism, say to our graduate English seminar in 1985, “We are all pluralists now.” Hassan seemed amazed by how fast the times were changing, even then.

The phenomenal growth of so-called American “roots musics” is kindred to Curry’s kind of art. And is the underlying idea of Curry’s art passe? Wisconsin’s progressive ideal is far from moribund. 5

Though only mildly modernist, Curry’s artwork has a straight-talking, “big-shouldered” heartland strength, akin to that which poet Carl Sandburg famously attributed to Chicago, Wisconsin’s big, noisy, dynamic neighbor.

And even before he ever got to Wisconsin, Curry understood and captured the historic, radical, and transformative import of abolitionist John Brown. Though not part of this show, his John Brown images are central to Curry’s legacy. He titled his incendiary mural of Brown, in the Kansas Statehouse, “Tragic Prelude.” The apt title allows the controversy and potency of John Brown’s legacy to resound through time, on its own terms.

In 1859, Herman Melville described Brown as “the meteor of the war,” in his superb poem “The Portent.” 6.

Curry shows us the meteor, ablaze.

“Tragic Prelude,” a mural portion by John Steuart Curry, in the Kansas Statehouse. Courtesy pixgood.com

Curry saw Brown as “a living symbol of mankind’s need to fight oppression,” wrote art critic Theodore Wolff, who knew the artist. 7 Also, Curry’s scenes of destruction from the 1929 Kaw River flood had produced wrenching images such as “Mississippi Noah” (1935), a black father imploring the merciless heavens, with his family and cat huddled on their cabin’s roof. Did Wall Street investors have it worse in 1929? And by the evidence of the photo below, today’s college students at Kansas University have embraced the vivid power of a Kansas artist, who died before their births, deemed too crude for wanna-be modernist Kansas critics.

Kansas University students brandish a modified reproduction of John Steuart Curry’s famous mural of John Brown at a KU sporting event. Courtesy www2.kusports.com

Yes, it’s a fast world. Still, as time passes, Curry’s tornadoes and firebrands — and his brawny Wisconsin landscapes and pulsing, progressive scenes — seem to stand taller, in the wind, in the stately clouds, and in the long light of history.

All reproductions courtesy MOWA, except as noted. For information, visit: http://www.wisconsinart.org.

_________________

A shorter version of this review was published in OnMilwaukee.com.

1 Thomas Hart Benton, “Wisconsin Landscape” an essay on Curry, in Demcourier, April 1941, 13

2 Aldo Leopold, “The Farmer as a Conservationist,” 1939 http://books.google.com/books?id=6HLo7ltlKP0C&pg=PA273&lpg=PA273&dq=Aldo+Leopold+John+Steuart+Curry&source=bl&ots=MrULoJSg6_&sig=xY8ea6Yn2Ld5m3YmCdM-=-] Q2tET4&hl=en&sa=X&ei=lnm9U5WmEIqNyATJr4LACw&ved=0CB0Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Aldo%20Leopold%20John%20Steuart%2

3 James M. Dennis, Renegade Regionalists: The Modern Independence of Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1998, 245

4 Author and journalist Charles Pierce is Esquire magazine’s chief political blogger, and contributes to ESPN and NPR. A Massachusetts native, Pierce graduated from St. John’s High School in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts and from Marquette University in Milwaukee, with a journalism major in 1975. So his perspective may be informed by both classic New England political values and Wisconsin’s progressive tradition. http://www.esquire.com/blogs/politics/The_Death_Of_The_Wisconsin_Idea?src=spr_TWITTER&spr_id=1456_140346841

5 Wisconsin’s progressive ideals regained international visibility with the massive populist protests and recall election against Gov. Walker’s draconian budget cuts and cronyism policies which undid, among other things, some of the work of a truly popular three-term Republican governor, Warren Knowles, who believed in another aspect of “The Wisconsin Idea”: “That it was possible to reduce political pressures on the governing process by putting professionals in charge of determining whether the books balanced,” writes John Nichols, in Uprising: How Wisconsin Renewed the Politics of Protest, from Madison to Wall Street, Nation Books, 2012, 74. To date, Walker’s flagship job creating agency WEDC has produced a documentable 5,840 jobs, ninth best out of 10 Midwestern states, barely a percentage point higher than Illinois, which Walker’s belittles for its job creation horrors. Yet he just hired an Illinois audit firm to investigate Wisconsin’s job creation. Who’s in charge here, doing what? http://www.progressive.org/news/2014/06/187732/how-many-jobs-has-walkers-wedc-created

Yet he just hired an Illinois audit firm to investigate Wisconsin’s job creation. Who’s in charge here, doing what?http://democurmudgeon.blogspot.com/2013/08/wisconsin-hires-illinois-auditor-to.html

Another excellent example of the state’s ongoing tradition is the annual political chautauqua Fighting Bob Fest, named for Robert LaFollette, which features an array of prominent progressive leaders, writers and activists. In recent years, the event has drawn upwards of 10,000 people. The festival will be held this year on September 13, at its original site in Baraboo, at The Sauk County Fairgrounds. For more information, visit

http://www.fightingbobfest.org.

6. “The Portent” is the opening poem of Melville’s under-appreciated work of poetic experience and evocation of the Civil War, Battle Pieces, and Aspects of the War. Prometheus Books, 2001, 11

7. Theodore Wolff, “John Steuart Curry: A Critical Assessment,” essay from John Steuart Curry: Inventing the Middle West, Hudson Hills Press, 1998, 87

Kevin,

While editing an essay I wrote a few months ago on Curry’s “Our Good Earth,” a Google search brought me to your excellent blog post. Reading it prompted me to update my meandering piece. It now cites your points about the golden-hued children who rise along with their father from the amber field of grain. Also helpful was the photo you included of Curry’s 1942 mural, which I hadn’t come across before. That pointed me to additional research and allowed me to weave some more speculation in support of my theory that Curry was influenced significantly by the 19th-century French artist, Jean-François Millet.

My post is at http://www.mikeettner.com/03/2014/john-steuart-currys-our-good-earth-an-american-makeover-of-millet/.

Thanks again.

Mike

Pingback: John Steuart Curry’s “Our Good Earth”: An American Response to Millet? « It’s Mike Ettner’s Blog