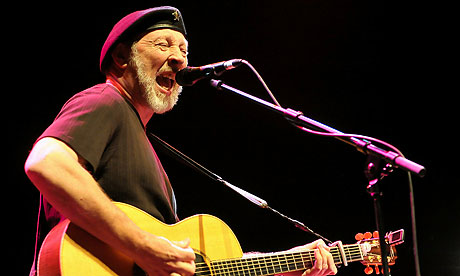

Richard Thompson sizzled on acoustic guitar on “1952 Vincent Black Lightning.” Courtesy willard’swormholes.com

The Pabst Theatre crowd leapt to its feet and roared, and you knew he was coming back. Not only that, 65-year-old Richard Thompson suddenly scurried back out to his guitar, like a kid pouncing on a Christmas present.

I’m standing the conventional concert review on its head because, as excellent as Thompson was from start to finish, the surprising end was so remarkable and telling. Thompson proceeded to play a seven-song encore with little prompting, including Otis Blackwell’s rollicking “Daddy Rolling Stone,” and Dylan and the Band’s “This Wheel’s on Fire.” It’s often said that Thompson feeds off of live audiences, and it helped that he was the event’s focal point, unlike his last time in town, when he opened for Emmylou Harris and Rodney Crowell. This was his audience. With all the bobbing gray heads in the audience, maybe he was helping keep us young.

But his boyish playfulness is fascinating to contemplate in that this man began the first major phase of his career drenched in tragedy, which seemed to inform the dark vision that persists to this day and adds edge, and incalculable depth, to his music, given Thompson’s songwriting talent and penetrating guitar playing.

I refer to the cataclysmic car accident in May of 1969 that shattered Fairport Convention, the seminal folk-rock band of which he was a charter member. A van accident killed the group’s drummer Martin Lamble and Thompson’s girlfriend Jeannie Franklyn, a gifted clothes designer, and injured two other band members. Yet, almost miraculously the group sorted through their shambles and psychic damage to produce, over the next five months, their nonpareil album, Liege and Lief.

They found a way to transmute their musical priorities, to produce haunted originals and a melding of ancient folk songs and contemporary rock. Yet, as with many traumas during formative periods, this one deeply colored this artist’s work. The same seems true of the breakup of his artistically rewarding marriage to Linda Thompson, which produced the masterful Shoot Out the Lights, after Richard left Fairport Convention.

What ensued was one of the most auspicious and consistent careers by a solo artist in modern times. Thompson was always a virtuoso on the guitar and he only grew as a instrumentalist and as a singer and songwriter, as his life experience did. Virtually every album was a novella of raw yet exquisitely crafted observation, rendered in a singing voice nakedly impassioned in its bracing Celtic tones and yelps of anguish, directly releasing the depths of masculine pain, wit, tenderness and irony.

The quality, power and beauty of his song craft would inspire, in 1994, one of the first of the now-fashionable songwriter tribute albums Beat the Retreat: Songs of Richard Thompson, which featured renderings of his work by R.E.M., David Byrne, Bob Mould, Bonnie Raitt, X, Los Lobos, Shawn Colvin & Loudon Wainwright III, Graham Parker, The Five Blind Boys of Alabama and other American and British Isles artists.

Thompson is blessed, or cursed, with an acute and scholarly sense of history, which prompted him to once produce a deeply researched tour and and album presenting, improbably but impressively, 1000 Years of Popular Music.

But for such a songwriter, society is inseparable from music, and an especially memorable life was “Al Bowlly’s in Heaven.” At the Pabst, he displayed razor-sharp political instincts in prefacing the song about a bitter WWII veteran by rhetorically asking: “Are veterans in this country treated like they are in ours, always losing out on their benefits and all?” Perhaps he was unaware of the recent firing of the head of the VA due to pervasive problems in veterans’ treatment and neglect. But his certainty of the song’s timeliness was spot on: “Al Bowlly’s in heaven/and I’m in limbo now.”

Sensing himself in time’s passage, Thompson has never rested on his laurels, and after nearly 40 post-Fairport albums, he’s produced one of his finest in his latest, Electric, the backbone of his repertoire in this tour.

He began the concert with the album’s opener “Stuck on the Treadmill,” which deftly ranges across oppressive work conditions to the threat of automation and the uncertainty of standing up for worker’s rights. It could be the anthem for today’s working-class or the slip-sliding white-collar middle class. He fairly spit out the lyrics: The money goes out/the bills come in/Round and round we go again/ I come close, but I never win./ Stuck on the treadmill./ Another day of punching steel/ Till my arms too numb to feel/ like a hamster on a wheel/ stuck on a treadmill! The lyric leads to: Strike’s coming, troubles brewing/whole town going to rack and ruin/Next year, what’ll I be doing?/Stuck on the treadmill.

The song resounded like a hammered anvil in working-class Milwaukee and collective bargaining-deprived Wisconsin.

Although many of his songs veer toward the Yeatsian sense of casting a cold eye on life, Thompson, like Yeats, sustains a tough compassion and sense of morality and justice. This was never clearer than on, “Good Things Happen to Bad People”: You stared me down without blinking/that’s when I really started thinking/you must’ve been running around/because you were smiling/Good things happen to bad people/but only– but only– for a while.

Yet Thompson can never be reduced to being merely a brilliant versifier. He knows the power of a lyric ultimately lies in its relation to its music. And he can extend emotional power and even a story’s tone and logic into his superb guitar playing.

Courtesy undergroundbee.com

As with many of his concerts, he let his guitar do serious talking on You Can’t Win, where his sense of outrage and irony sustained profoundly into a deep and wide-ranging solo that brought a standing ovation. This video helped me relive the number, (his solo begins at the five-minute mark): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aLypHd3hJdU

He’s less blues-based and falls just shy of Eric Clapton’s peak intensity, yet Thompson. nevertheless sustains power and invention with a flintier guitar tone, an engaging formal logic, and more musical resources — from a slightly outrageous, sometimes sardonic array of dissonant, bent-string chordal shards, to octave leaps, to a melodic sensibility infused with curling Celtic folk melody and harmonic motion, especially the strutting Scottish bagpipe march rhythm, injected into electric guitar.

He possesses a marvelous sense of tension release: From a white-noise roar climax he unfurled a majestic line curling back and lashing itself. I’ve listened to his solo on the above video a handful of times and hear something fresh each time. And his “You Can’t Win” solo at the Pabst was longer, and perhaps better.

During the encore, his finger-style chops positively sizzled on acoustic guitar, especially in his self-accompaniment to his classic motorcycle saga, “1952 Vincent Black Lightning.”

This trio drives with the propulsive thump of drummer Michael Jerome, who used the whole kit as a sequence of prodding retorts. He fairly thrashes his drums but never laboriously like many rock drummers, rather with a deft, encompassing sense of contrast and accent. This elevates the rhythmic discourse, allowing Thompson’s guitar to up the ante without seeming showy, but riding the tidal crest, underpinned by bassist Taras Prodaniuk, who resembles a youthful David Letterman. If only Dave could’ve jammed with Paul Schafer like this, he might’ve lasted another decade on The Late Show — or had a heart attack years ago.

Richard Thompson’s Electric Trio includes longtime drummer Michael Jerome (above) and bassist Taras Prodaniuk (lower) Photos courtesy gapersblock.com

It’s understandable how the bandleader chose Jerome as a longtime percussion mate, who can be heard and seen as early as 2001 on Richard Thompson Live in Austin Texas (from the invaluable Austin City Limits concert video series). Jerome’s style strongly resembles that of Dave Mattacks, the crucial drummer with Fairport Convention. *

I wrote the above description of Jerome’s drumming and then encountered Rob Young’s excellent characterization of Mattacks. Compare Young’s description: “In his hands, the beats fall with a heaviness that seems to gouge at the earth itself, fleet footed enough to avoid getting bogged down…The funky plod of Mattack’s drumming proves the ideal foil for the mushy instrumental palette of English electric folk, propelling its accordions, fiddles, abrasive guitars and astringent harmonies forward without denying their bulk and grit.” 1

In his current Electric Trio, Thompson feeds off that loamy boil of rhythms and seems to funnel the accordions, fiddles, abrasive guitars and astringent harmonies into his guitar and music.

May he continue to feed himself and his audiences on the most elemental, and complex, of musical experiences, until “the spell is broken.”

_______________

* As historian Rob Young has suggested, Fairport was the closest British equivalent to The Band, in terms of its role in drawing from a deep wellspring of folk vernacular sources and synthesizing it into a resonantly hoary musical language and sensibility. Though they sounded very different, both bands helped demarcate post-psychedelic roots music.

For my part, being a huge fan of The Band, I recall playing Fairport’s Liege and Lief as much as I played The Band’s eponymous second album. Both are astonishingly fascinating cultural artifacts and innovations, aside from the supreme quality of the music.)

1 Rob Young, Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music, Faber and Faber, 2011,

256