b

b

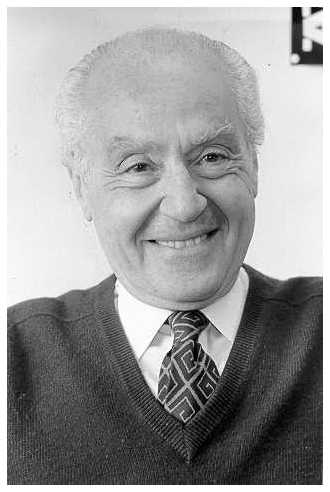

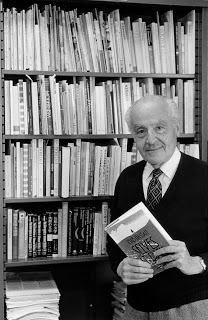

Courtesy ihabhassan.com.

A celebration of Ihab Hassan’s life and a memorial will be held at 3:30 p.m. on Nov. 19 at the Zelazo Center, 2419 E. Kenwood Blvd, at the UW-Milwaukee, as part of a symposium that Hassan helped organize. It is free and open to the public.

By Kevin Lynch, UWM BFA ’73, MA English ’87

In these instant-gratification times, literature may seem a hoary, aging hero, a seeker with a backpack of musty books, plodding along the shore, risking being swept away by a tidal wave of technology.

I, for one, keep plodding, partly because my passion for literature was rekindled right when I was ready for it. A leave-of-absence from The Milwaukee Journal in the late 1980s helped me open another door. I began a Master’s degree program in English and encountered the most remarkable teacher of my life, Ihab Hassan. The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee English professor emeritus died of a heart attack at 89 in Milwaukee on September 10th.

He is “arguably the most famous professor in the history of UWM,” Dave Clark, the school’s associate dean of humanities, told Journal-Sentinel obituary writer Meg Jones. “Now this is coming from the humanities dean, of course. But he’s an incredibly well-known international figure, widely credited with coining the current contemporary use of the term postmodernism.” 1

Indeed, the term – Hassan’s prescient insight into a tectonic shift in contemporary culture — was precise and resonant because it acknowledged the epic cultural force that modernism had on the way we live, think and understand each other, person-to-person, nation to nation. In retrospect, “postmodernism” might seem an unimaginative term because so many observers have aped its clear distinguishing function. Now we have “post-this-that-and-the-other-thing.” That showed Hassan’s influence, and his defining of the term helped clarify all the confusing reactions to the monumental anti-conventions of modernism, which was co-opted by absorptions of power, as Hassan understood quickly. Yet the rather inelegant term “post-modernism” was not characteristic Hassan, who was a lapidary wordsmith, among the most gifted and sometimes mandarin literary stylists I have ever read. His sumptuous vocabulary often challenged mine. “He just loved words. He gloried in them,” said Liam Callanan, a UWM associate professor of English. “He was absolutely the youngest octogenarian I ever met. He would have been young at any age, for his language. It was like watching a talented woodworker or sculptor at his craft.”

Beyond being a great literary critic, Hassan excelled as a teacher. He ingeniously demarcated the differences between modernism and post-modernism by creating a chart which listed terms of modernism with another column for the terms of postmodernism, which correlated most meaningfully to each modernist term. For example, Modernism: art object/finished work. Postmodernism: process/performance/happening. Have your dictionary ready for this list, but it clarifies the era’s often-confounding transition of thought and ideology as concisely as anything. 2

At a personal level, he possessed a certain Olympian air that inspired a tinge of awe, so it wasn’t necessarily easy to approach him. This Egyptian émigré was lean and handsome, with wavy silver hair, an impeccable dresser. He had a way with female students though he seemed devoted to his longtime wife and sometime-co-author Sally Hassan.

And yet, in literature’s often ambiguous and relative realm of judgment and interpretation, he loved to tease out insights from students. In our graduate seminar “Backgrounds to Modernism,” I was extremely gratified when I would answer a question he posed and he’d say, “Precisely!” with satisfied delight. In this class I read such modern classics as Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, Freud’s Civilization and its Discontents, T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, Georg Lukac’s History and Class Consciousness, and Kafka’s The Trial. Heavy tomes, but Hassan made them compelling and important to us and our civilization.

Unforgettably, almost mysteriously, his affinity for Martin Heidegger in his abstract but beautiful book Language is the House of Being made me love a part of Heidegger’s capacious mind that seemed to utterly transcend his apparent Aryan racism. Remember, Hassan was an Egyptian, whom the Nazis probably would’ve ostracized if not exterminated. I did my term paper on Kafka and, with deft written comments he told me I had a “special feeling” for Kafka. Me? I felt like a knighted everyman who would later deeply connect with a Kafka precursor, Melville’s seemingly hapless scrivener Bartleby.

Hassan’s constructive critique also helped me to better guide a reader through my written thoughts with more signposts, to emphasize structural clarity. It wasn’t until years later, when I encountered a few lesser professors at Marquette University, that I realized how luminously Hassan had genuinely helped this student to succeed, and to become a better teacher.

And I’ll never forget one of his most offhanded, intimate seminar moments. As several of us chatted with him after one class, he summed up the groping conversation by saying, “Now, we are all pluralists.” The comment gently lifted us up to his windswept vista of broader, deeper understanding. At that point in time, pluralism — a non-confrontational, more inclusive term for the burgeoning multi-culturalism and globalism movements — signaled a cultural shift just beginning to groan into place, after postmodernism. 3 His observation in 1986 foretold the still-nascent Internet’s collective dynamics and ways of being, as Heidegger put it. Hassan didn’t hang on to one great accomplishment as time passed. He noted that predecessors used the term “postmodernism” before him, but he “stuck with the term and tried to clarify it.” 4 Humble and wise, he sidestepped his own renown and kept reading the zeitgeist. He decried the self-referential, insular specializing that began reducing so much “post-modernist” theory to academic or esoteric play.

As a professor of such cosmopolitan range and brilliance, Hassan gained international renown. He was a visiting professor in Sweden, Japan, Germany, France and Austria as well as schools in the United States. He won two Guggenheim Fellowships, in 1958 and 1962, and three Senior Fulbright Lectureships in 1966, 1974 and 1975.

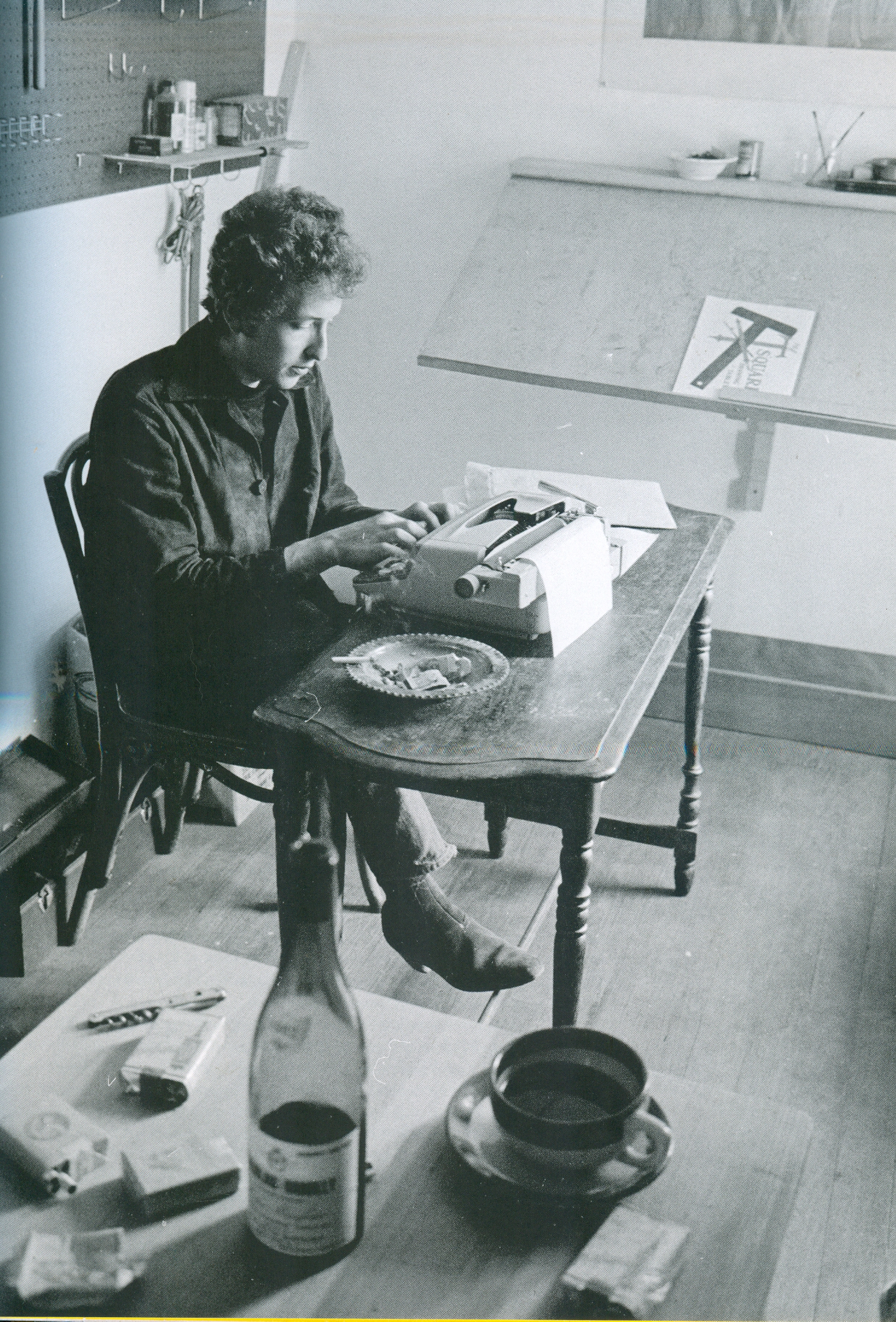

Hassan’s “Radical Innocence” which reached mass-paperback audiences, is a classic examination of the contemporary American novel of the 1960s. Courtesy amazon.com.

So it was a huge coup for UW-Milwaukee — the little brother of the magnificent UW system’s jewel in Madison – to snag him in 1970. By then, Hassan sought a deeper sense of the peculiarly American mindset and genius, perhaps buried in the heartland somewhere. This Middle Eastern Americanist with his deep “background in modernism” had found a new concept for apprehending our native literature in his pioneering book Radical Innocence: The Contemporary American Novel published in 1961. He laid out important early templates for understanding Gore Vidal, James Baldwin, William Styron, Jack Kerouac, Ralph Ellison, Flannery O’Connor, Norman Mailer, John Cheever, Truman Capote, Saul Bellow, Carson McCullers, JD Salinger, Bernard Malamud and others – yes, a head-spinning literary hodgepodge that he made coherent. And the best short introduction to American literature I know of is Hassan’s 194-page Contemporary American Literature 1945-1972: An Introduction.

For me, and doubtless many others, the fact that he came from a Middle East culture as ancient as Egypt’s helped endow him, I believe, with an almost oracular perspective that I’ve never experienced with any other professor. Consider his small book Out of Egypt: Scenes and Arguments of an Autobiography in 1986. When she gifted the book to me at Christmas in 1986, my wife at the time, Kathy Naab, inscribed: “Follow a wise man out of Egypt and into the nether reaches of ‘reason, dream and love.’” Those three words gave you a sense of the range of his thinking, yes, even encompassing the intellectually derided ideas of “love” and “dream.”

In the autobiography, Hassan observed: “A Marxist, Zionist, or feminist may prove no more rational than some ‘mystics,’ yet no stigma attaches itself to their commitment. Is it because men forgive attachments to factions, fractions — my side, your side — but never to the whole? The threat of mysticism: not vagueness or unreason, but a loyalty wider than most of us can bear. In short, Eros diffused, the Self dispersed, the end of paideia.” 5

An exemplary book of Hassan’s mature period as a critic is “Selves at Risk: Patterns of Quest in Contemporary American Letters.” Courtesy amazon.com.

Courtesy yoyoseimo.blogspot.com.

And yet, despite his fame and glamor, he was the only teacher I’ve ever known who invited his students to his home for a seminar. On the last class of the semester, we came to the professor’s spacious residence on Terrace Avenue, overlooking Lake Michigan. Along the length of the connected living room and dining room stood one long wall of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, jammed full, the most books I have ever seen in any home. Our gracious host then made a discussion of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame far less dire and bleak than it might have seemed otherwise.

My esteem for Hassan only grew in the years after his seminar, as I became an enthusiastic Americanist, in music, literature and art especially but particularly when I took the deep dive with Melville. I wrote a hopefully-forthcoming book called Voices in the River: The Jazz Message to Democracy, which explores the relationship between jazz, creative writing and the democratic process. I quote Hassan in it, and at one point was inspired to called him up from Madison, out of the blue, a student he’d had for one seminar 15 years earlier. He said he remembered me, and then I began babbling about my book, until Hassan deftly interrupted me. He chuckled and said, “You really don’t have to tell me your whole book. But it sounds like you have an excellent subject. Good luck with it.”

His words were golden to me. I imagine numerous UWM graduates have comparable memories of Ihab Hassan. After he retired, he continued to write, publish and stay active at UWM, and was helping organize a symposium Beyond Crisis: The Humanities in Renewal on November 19 at the Zelazo Center.

That date will now include a memorial event for Hassan, open to the public.

One of his major mature works was Selves at Risk: Patterns of Quest in Contemporary American Letters. At one point in the book, he stands on the shoulders of no less than Ralph Waldo Emerson and, indeed, sees further, regarding the human drive to quest:

“In the end, some Emersonian Whim is at the bottom of all quest, I think. But something else, too, that Emerson neglects: a wound. For the adventure/seeker is mainly a Westerner, scion of the rich of the earth, drawn to the wretched by a need, a dis-ease, they may find ludicrous. Though he may be neither soldier nor colonizer, domination no less than quest is the motive of his history and its deep wound. But this is also the wound from which history flows, sometimes suppurates. His flight from modernity cannot avail, nor his search for lost innocence, nor his nostalgia for otherness. His yearnings for desolation, of sand and snow, in Arabia or Antarctica, lead him to an abandoned Coke bottle more than (Wallace) Stevens’ jar ever ruled the hills of Tennessee. 6 Yet his will, malaise, disequilibrium, some radical whim or will or asymmetry in his being, has made our world knowable, made the world we know. Edging cultures, hedging histories, acting briskly, most often alone, the seeker — man or woman — gives us an indestructible perception that, from our best selves, speaks to all.”

His last published essay, in the current Antioch Review, is among his finest and most plain-spoken, a searing defense of the humanities that ranged from the humanist’s mightiest archetype Prometheus to Nietzsche, William James and crucially Steve Jobs. He titled it The Educated Heart: The Humanities in the Age of Marketing and Technology. He full understood the humanities’ limits, but finally he writes “Who, besides artists and writers — yes, and humanists — will speak to us of truths that we cannot prove but know in our marrows bones?” Hassan helps us know the nature and quality of those truths, as well as anyone. 7

In the end, his educated heart gave out, but never his intellect, passion or spirit. Ihab Hassan, born in Cairo, quested far around the globe many times. He was the best of questers, even in the worst of times. And he spoke indestructibly to all, to our best selves, our better angels.

- http://www.jsonline.com/news/hassan-coined-term-post-modernism-for-change-in-60s-literature-b99576689z1-327595561.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ihab_Hassan

-

3. In Spring of 1986, Hassan explained this issue in a major essay “Pluralism in Postmodern Perspective,” in Critical Inquiry 12, 503, published later in his essay collection The Postmodern Turn: Essays in Postmodern Theory and Culture. Ohio State University Press, 167

4. Postmodernism, etc:* Interview with Frank Cioffi http://www.ihabhassan.com/cioffi_interview_ihab_hassan.htm

5.Ihab Hassan, Out of Egypt: Scenes and Arguments of an Autobiography 1986, Southern Illinois University Press, 79. With that last word of the quote, you see what I mean about Hassan’s vocabulary, and his philosophical perspective: Paideia: Ancient Greek Hist. Education, upbringing; spec. an Athenian system of instruction designed to give pupils a rounded cultural education, esp. with a view to public life. Hence: the sum of physical and intellectual achievement to which an individual or (collectively) a society can aspire; a society’s culture. From the Oxford English dictionary online http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/135951?redirectedFrom=paideia#eid

6. Hassan alludes to Wallace Stevens’ well-known poem “Anecdote of the Jar,” which explores the question of the superiority between art and nature.

7.http://review.antiochcollege.org/fall-2015