![IMG_0186[1]](https://kevernacular.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/IMG_01861.jpg)

The Tedeschi-Trucks Band at the Orpheum Theatre in Madison Saturday night. Photo by Kevin Lynch

I promised myself I wouldn’t do a full review of this whole concert and I really won’t, because I’ve written about the consistently remarkable Tedeschi-Trucks Band extensively in the last couple years.

So, frequent readers of this blog, bear with these remarks.

But seeing the band last night much closer up than I did at Red Rocks Amphitheater the summer before last, I gotta say: Synergy, inspiration, surprise, telling detail, emotional truth and buckets of soul. Like the great sprawling Southern oak tree projected as the band‘s stage backdrop, they seem to replenish their freshness and power the older they get. Considering they’re still only a few years old as a unit, they convey a rare assimilation of the deep, entwining cultural roots that they draw from, which conveys a far greater age than their temporal years.

One of the most impressive aspects of this group is that — though it gains a big, enthusiastic audience, especially at live shows, from its power and skill with rave-up type numbers — it also possesses deep, thoughtful and lyrical dimensions.

And the way they often segue from a powerhouse tune directly to a quieter one like “Midnight in Harlem,” one of their trademark songs, suggests how they relate one sensibility to the other. After a loud rock-out, Trucks slid seamlessly into his slide guitar raga-esque improv introduction to “Midnight,” one of the more sublime songs in popular music today. Keyboardist-flutist Kofi Burbridge set another layer of the finely-sketched scene with his simmering organ, stoking a groove that ripples like wind through trees. Written by gifted backup singer-songwriter Mike Mattison, the song’s a concise, beautiful short story of diminished but dogged expectations, partly a testament to America’s countless forsaken, “I saw old man’s shoes, I saw needles on the ground…” midnight in Harlem, midnight in Anywhere, USA.

Set in the context of a long subway ride, the narrator witnesses and deeply feels the exposed naked city yet somehow, in the face of windblown streets and the “subway closing down,” he remains steadfast, now walking, yet riding a metaphoric train of hope, a moonlit dream. Then Derek Trucks musically pinpoints the tragedy — and the dream’s inextinguishable flame — in his magnificently-built guitar solo, like a steady fire in America’s heart. Of course, having a woman singing a song penned by a man also gives “Midnight in Harlem” gender universality.

Another set highlight was “Idle Wind,” the most luminous song on their last album Made Up Mind.

It’s built around a fine oceanic image that recalls some of Ishmael’s lyrical reveries in Moby-Dick which is, of course, among many other things, a great coming-of-age story, as is “Idle Wind.” Hear Tedeschi sing these cross-currents of lyric, idea and musical radiance:

How I wish I could fly

Like a bird in the summer sky

Just a ship with a sail

In an idle wind, idle wind

Now I’ve got things to do and I’m telling you

And I don’t wanna stay anymore

And when I was a child I’d dream on high

Now I’m old and I don’t really care

I’m just trying to make somebody happy

I’m just trying to make somebody smile

In the middle of “Idle Wind” arose an extended duet by the band two drummers, JJ Johnson and Tyler Greenwell, that added a feisty dimension to the song, while remaining tasteful, musical and engaging.

My point is that such literary and dream-based songs serve to offset the predominant powerhouse blues, gospel and jazz gumbo that burbled throughout the concert with a rich dynamic range.

Derek Trucks and Susan Tedeschi and their collective-style band consistently display a deep love and understanding of the roots of American vernacular musics. Courtesy isthmus.com

They closed the set with their surefire rave up, “Bound for Glory.” The groove’s heaving, funky sway and the call to shared spiritual ecstasy is nearly irresistible, especially when they reach the refrain’s climax, where Tedeschi again attained an almost outrageous level of soul-scorching exhortation, and Trucks unleashed one of his most incendiary guitar salvos.

A few words about presentation, regarding Susan Tedeschi. She knows how to display her earthy beauty with self-assurance, but without ever primping or strutting onstage, like most pop divas do today. Half the time she wears specs onstage, probably to see her guitar fret board on tunes she doesn’t have completely under her fingers. This is a serious musical artist, not a “chick singer.” Her every action and expression directly serve the music, which all authenticates her physical presence.

Late in the show, two brilliant covers proved telling, one preceding “Bound for Glory” and one after, the first encore. Two covers at such a juncture in the concert suggests a lack of new material that they feel is performance-ready, but also their superb skill in cherry-picking and re-invigorating strong material in the roots music canon.

The band tore into the former song, “I Pity the Fool (Who Falls in Love with You)” with lusty abandon. In1967, The Paul Butterfield Blues Band recorded ostensibly the definitive version of this old R&B song on their superb horn-powered album The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw. The irrepressible Tedeschi and her big, brawling band lifted Butterfield’s take to new heights (though I’d have loved to have heard Butterfield do it live.) In the middle of “Fool,” Tedeschi ripped off the nastiest guitar solo I’ve ever heard her play, conveying the bruised defiance of the song’s jilted lover. Trucks followed with a cooler, mewling slide solo which evoked actual pity.

And then the encore: “I’ve Got a Feeling,” one of the ballsiest Beatles rock ‘n’ roll songs of their late period (from the Let It Be album). Here again, the band found the “feeling deep down inside” right in their wheelhouse and knocked it out of the park.

Speaking of sports references, Wisconsin winning a huge NCAA basketball tournament game to advance to the “Final Four” — right before the concert started — hardly hurt the esprit de corps of the wildly enthusiastic, sold-out crowd at the Orpheum Theater.

Susan Tedeschi’s parting words: “Good luck in the Final Four, I know you guys are gonna do great.” She’d begun the concert with a conspiratorial smirk, “Congratulations on winning …I know you won, because you’re in my bracket.”

I have no need to temper my previous assessment of this band as the best I’ve heard on tour (and on record) in today’s popular music — for their stylistic range, depth of talent and inspiration, which I’ve discussed previously in this blog. In fact, having just heard live the excellent Gregg Allman band about a week earlier, I realize how much TTB has also raised the bar for the great tradition of Southern blues-rock vernacular music, which the Allman Brothers Band once defined.

Enthusiasm for this band of old souls spans several generations. A twenty-something sitting next to this baby boomer often responded physically to the performance throughout the set. Early on, she exclaimed to me about Trucks’ brilliance. At the end, she turned to me with her eyes aglow. I said, “I could’ve listened to two sets of that.”

“I could’ve listened to four sets of them,” she said.

________

Special thanks to Eric Schumacher-Rasmussen and his brother-in-law Tom Clark.

For those who care to see and hear just what I reviewed, here is a Yahoo live posting of the TTB’s March 28 Madison performance. https://screen.yahoo.com/live/event/tedeschi-trucks-band

Here’s an excellent radio interview with Derek Trucks before the band’s Orpheum Theater performance in Madison by Stuart Levitan, host of Books and Beats, on The Mic 92.1 in Madison: http://www.themic921.com/media/podcast-books-and-beats-with-stu-SundayJournal/books-and-beats-hr-1-032215-25920062/

Underappreciated Detroit-born guitar innovator Harvey Mandel performed as guest guitarist with the Gregg Allman Band Wednesday night. Photo courtesy chicagobluesguide.com

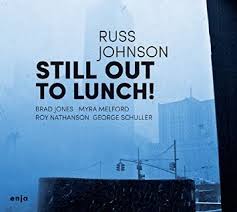

Underappreciated Detroit-born guitar innovator Harvey Mandel performed as guest guitarist with the Gregg Allman Band Wednesday night. Photo courtesy chicagobluesguide.com Russ Johnson — Still Out to Lunch! (Enja)

Russ Johnson — Still Out to Lunch! (Enja)