Duane Allman died 41 years ago today. It reminds me of how long ago I heard something new rising from the South. I’d bought a new album by a group from Macon, Georgia simply titled The Allman Brothers Band. I let the needle down into the vinyl grooves and my speakers burst with roaring blues-rock, vocals dripping with an earthy Southern growl, polyrhythmic drums (yep, two drummers) and searing double guitar work.

Duane Allman died 41 years ago today. It reminds me of how long ago I heard something new rising from the South. I’d bought a new album by a group from Macon, Georgia simply titled The Allman Brothers Band. I let the needle down into the vinyl grooves and my speakers burst with roaring blues-rock, vocals dripping with an earthy Southern growl, polyrhythmic drums (yep, two drummers) and searing double guitar work.

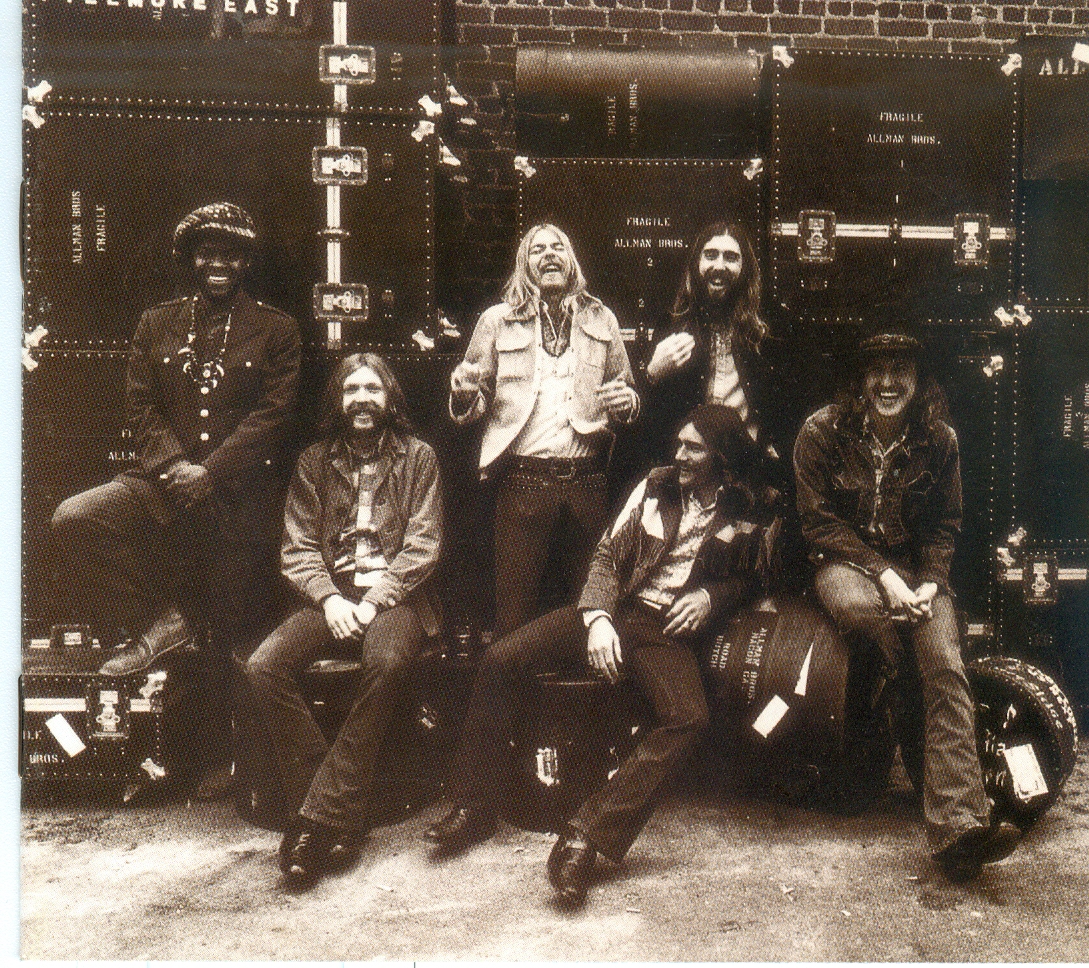

The album cover, a sepia-toned group portrait, exuded steamy old Savannah’s “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” atmosphere.

Plus, they had the guts and talent to open their debut album with an instrumental (“Don’t Want You No More”) which blended blues, rock and some Jimmy Smith-style grits-groove organ.

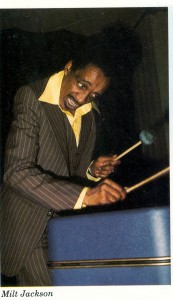

I was already a pretty serious jazz fan as well as an admirer of such good improvising rock-blues bands like The Grateful Dead, Cream, Jefferson Airplane and The Butterfield Blues Band.

Next thing I knew, the Allmans hit Milwaukee on a northern tour. So I had to check them out. I walked into The Scene, a hip downtown music club (where Jimi Hendrix and Miles Davis had played) and the band had just launched into something they called “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.”

It lasted about 12 minutes and didn’t contain a single word. By the end I was floored. 1

Not unlike the well-known version on The Fillmore Concerts, this “Elizabeth Reed” opened with guitarist-composer Dickey Betts’ languid dynamic swells, like dragonflies hovering over a porch of faux-Roman pillars graced with bottles of Southern Comfort. Then the melody arose, a wisp of lyrical reverie, followed by a march-like bridge to the main body of the piece. Allman biographer Scott Freeman has compared Betts’ intro to Miles Davis’ trumpet. That wasn’t the only jazz connection, besides the ensuing improvs. As on the Fillmore recordings, the band was swinging as much as it was rocking – the double trap sets unfurled a splashing flow, then accelerated into a bustling Latin surge beneath the solos — with bassist Berry Oakley lubing the motion. Freeman compares Duane’s Fillmore “Elizabeth Reed” solo to John Coltrane, a bit grandly. 2

For sure, guitarist Allman does fire up bursts of incendiary heat and builds his solo with a superb sense of dramatic form and climax. Brother Gregg’s organ flows like a deep rolling river.

Here’s the band in New York doing “Elizabeth Reed” a few weeks after I saw them in Milwaukee http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8UwkBmDMfR4

“Dickey Betts’ song, thank you,” Greg Allman calls out at end, at the Fillmore. I think he did the same in Milwaukee. This was a serious band. The tune’s lyrical ardor would emerge as one of the group’s strongest expressive strains in such hits as “Ramblin’ Man” and “Blue Sky”and the breathtaking instrumental “Jessica” – – music with gloriously dancing solos and counterpoint over a rhythm section that had grown telepathic. “Lord, you know it makes me high, when you turn your love my way.”

The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East in 1971 ( L-R Jaimoe – drums, congas and timbales; Duane Allman, guitar; Greg Allman, organ and vocals; Dickey Betts (foregound) guitar; Berry Oakley, bass guitar; Butch Trucks, drums and tympani. Photo by Jim Marshall.

The band had made a poor impression, however, in front of industry professionals in their debut Northern gig, in Boston in December of 1969. (Freeman 57) The agents, bookers and critics felt something was missing.

Right. There was no hammy lead singer out front, miming oral sex with a mike. The Allmans’ vocalist sat workmanlike behind a big Hammond B-3 organ and the rest of the band just stood and played, as they did in Milwaukee, with a magnificent fire. Duane Allman’s droopy walrus mustache lent him an almost comically dolorous expression.

But this was a great band to me, and soon to countless others. The Allmans served up a hot, fresh gumbo that sounded as deeply American, in its way, as The Band had, though in a more rock-blues-jazz modality that spoke, sonically and lyrically, of the modern Southern experience, yet haunted by its history. It sounded like the best new American music I had heard from my generation in a while. There are reasons why the Allman Brothers became the most popular touring band in America in the early 70s — even with all that long jamming. It said something for what people were open to absorbing in a live concert regarding creativity that might risk big, American-style gestures.

Even the largely self-contained genius composer-guitarist Frank Zappa honored the Allmans by recording a long rendition of their monster jam staple “Whipping Post.”

Zappa’s version has an element of parody to it, knowing well that “Whipping Post” has launched thousands of concert matches, as an Allmans encore request. The shout “WHIPPING POST!” is now an old joke in rock music lore, a fan request that many bands must endure.

A Southern writer, Mark Kemp, has delved into the complexities of the emotional experience the Allmans convey on a moody song from their debut album called “Dreams”: “I went up on the mountain/To see what I could see/ The whole world was falling/right down in front of me.”

Kemp felt he knew what Allman was talking about — the social chaos of Civil Rights era de-segregation ironically produced new kinds segregation in the South before actual integration could occur. Integration among musicians had preceded the more agonizing integration of the larger Southern society, so now musicians found themselves caught in this new bind of social self-consciousness and political correctness. Suddenly everything in white-black relations was charged with the tension of liberation from the long white Southern social oppression.

The problems were understandable but things changed radically when Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Kemp quotes ace white session musician Jimmy Johnson, from the legendary Muscle Shoals Studios, recalling that suddenly he and other white players, who’d backed great black artists like Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett, were no longer welcome on dates with black players.

“Wrong seemed right and right seemed wrong,” Kemp writes. (Kemp xii)

As a Northern fan of the Allmans, I’m fortunate to not have the Southerner’s experience as a burden, though I greatly appreciate Kemp’s insightful, candid testimony.

The second Allman Brothers album Idlewild South came out within a few months of the 1970 Milwaukee club date I witnessed, and it included Elizabeth Reed. But the album opened with an exhilarating gospel rave-up “Revival” and featured “Midnight Rider,”an evocative bit of myth-spinning: “I got one more silver dollar. But I’m not gonna let ‘em catch me, no, not gonna let em catch the midnight rider.” I played the heck out of the album, reliving The Scene gig.

Betts had taken the title to Elizabeth Reed from a gravestone he’d encountered along a river he often visited for solitude. Betts claims the tune was actually written for a girl of Italian descent, which is why it has a Latin feel to it (Freeman).

There was also something else in the band, especially going back to the song Dreams — in Duane Allman’s slide guitar, by turns caustic and bereaved — the melancholic remnants of a complex sense of loss, which perhaps all mindful Southerners live with in the long shadow of the Civil War, in their inchoate dreams, including the suppression, sublimatiion or shedding of racist impulses. That perceptual prejudice was merely more obvious and honest than in much covert Northern racism.

And the Allmans emerged from the South right when the music business began trusting a whole concert to a single group. Bill Graham had pioneered this with his famous Fillmore West and East venues. In the San Francisco space Graham would daringly pair one of the new rock groups with a big-name jazz band, eg. Led Zeppelin with Woody Herman’s Thundering Herd. Yet unknown names were also born there.

I once saw Carlos Santana help give a skinny, bushy-haired teenage guitarist a career break at the Fillmore West, by letting him come onstage and jam with Santana. The 16-year-old Neal Schon later gained fame in Santana’s band and as lead guitarist with Journey. The times they were a changin’.

Fortunately for the Allmans, Graham booked them unheard at Fillmore East in November of 1969 because their manager, Phil Walden, had managed Otis Redding (until the soul singer crashed into Madison’s frigid Lake Monona in December of 1967). That’s all Graham needed to know. (Freeman 59)

The next time I saw the Allman Brothers live they played in the Milwaukee Arena, the basketball Bucks home court. Their style hadn’t really changed much but they’d matured as a group and Dickey Betts’ gift for country-inflected lyricism had fully emerged. A superb pianist, Chuck Leavell, helped fill the gap after Duane Allman’s death (see 1 below).

They became the model for Southern rock bands to this day, from Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Marshall Tucker Band, The Charlie Daniels Band and Little Feat to Widespread Panic, Gov’t Mule, The Drive-By-Truckers, Kings of Leon and the Derek Trucks Band, led by the nephew of Allmans’ drummer Butch Trucks. Martin Scorsese would include an Allmans collection in the set of albums released in conjunction with his film series Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues, which includes a 19-minute live version of You Don’t Love Me, to testify to the centrality of the band’s improvisational powers.

Of course, a career peak for Duane Allman was recording the album Layla with Eric Clapton under the guise of Derek and the Dominoes. The two guitarists challenged and inspired each other to extraordinary levels of passion singing, songwriting and interpretation, as well as blazing guitar work.

It marked an occasion when these two musicians seemed to break through to a new stratosphere, by plumbing and redefining the blues, as white musicians doing justice to this profoundly rooted African-American men cultural form, by going out on a limb and letting their hearts and souls hang naked, in the deep sway of mutual conviction, commitment and genius. Riding a pile-driving rhythm section, Allman and Clapton reminded us of the universality of the blues, as if searing a black “BLUES” brand on our collective consciousness.

The two-record set adds up to one of the greatest albums of any American vernacular music, at once sui generis and a portrait of an America of many familiar hues.

Among Layla’srough-and-ready jewels are “Bell Bottom Blues, “Anyday,” “Key to the Highway, “Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad?” “Tell the Truth,” “Have You Ever Loved A Woman?”, Jimi Hendrix’s “Little Wing,” “Thorn Tree in the Garden” and the remarkable title song, a love ode thatl, in seven minutes achieves, a near-epic emotional sweep through the piano-led suite-like transition to a lyrical embracing of life’s vicissitudes, which releases the tension song’s central expression of abject romantic desperation: “Layla, you got me down on my knees!”

But the Allman Brothers story all began with troubled dreams, as do many creative ventures. Perhaps another way of imagining the dreams that Greg Allman grappled with is to consider the struggle toward resolution also expressed in a person’s dream by a great Northern writer, Herman Melville, in the final poem of Battle Pieces: Aspects of the War, his collection of Civil War poems. Melville abhorred slavery but by the war’s end was deeply sympathetic to the people of the South. At the time, his poems were criticized for their lack of patriotic Union fervor. Robert Penn Warren has noted how, in the last poem of Melville’s collection, titled America, “the contorted expression on the face of the sleeping woman as she dreams the foul dream of earth’s bared foundations, is replaced, when she rises by a ‘clear calm look’”:

…It spake of pain,

But such a purifier from stain –

Sharp pangs that never come again –

And triumph repressed by the knowledge meet…

And youth matured from age’s seat –

Law on her brow and empire in her eyes.

So she, with graver air and lifted flag;

While the shadow, chased by light,

Fled along the far-drawn height,

And left her on the crag.

Warren continues: “’Secession, like Slavery, is against Destiny,’ Melville wrote in the prose Supplement to ‘Battle Pieces.’ For him, if history was fate (the ‘foulest crime’ was inherited and was fixed by geographical accident upon its perpetrators), it might also prove to be redemption.” 4

So time plays out its role in the South, foul crime an inheritance, as is its time and history. By 1969, Greg Allman’s dream of “falling down a mountain” may still be part of the long arduous historical process that began in 1866 with light chasing the shadow along the “far-drawn height,” and a woman “left on the crag.” Her dream may have begun a historical process, of multiple climbs and falls. So in 1969, the struggle to the mountaintop, a dream shared famously by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., began again. King was buried by then, killed the year before by a petty criminal/drifter. But others would get there, he believed.

The redemption of the Allman Brothers tradition emerged full-blown in 2011 with two extraordinary albums Greg Allman’s low country blues and the Tedeschi Trucks Band’s album Revelator .

Actually the tradition needs no redemption and Revelator more precisely represents a fresh expansive evolution, the marvelous gumbo of country blues, Allman Brothers jam soul power, vocalist-guitarist Susan Tedeschi’s remarkable amalgam of influences as a powerhouse singer, and gospel-jazz-R&B horn riffs and texture, topped by Derek Trucks’ soul-searing guitar.

There’s a handful of songs on the album that are the best she’s ever recorded, says Trucks, the singer’s husband. Tedeschi comments that she tried to sing as appropriately as she could for each song, which did not mean choosing a generic interpretive approach. “I’m not sit down and thinking I’m going to belt. I’m going to be real gospel -ey here I’m gonna be real country-pretty here. I’m not really thinking that; I’m just thinking what’s going on here musically and how can I put my heart into it and be as honest as I can.”

“She doesn’t have to belt and do the thing that she does so well in all the tunes,” Trucks says. “She really got comfortable singing in the lower part of her register, the sweet part of her voice, which I really love.”

Tedeschi adds. “It’s part really pretty intimate storytelling, and then we have some songs that are soul-gospel so I think it’s a nice mix.” http://www.vevo.com/watch/tedeschi-trucks-band/susans-vocal-approach/USSM21100891?source=ap

____________________

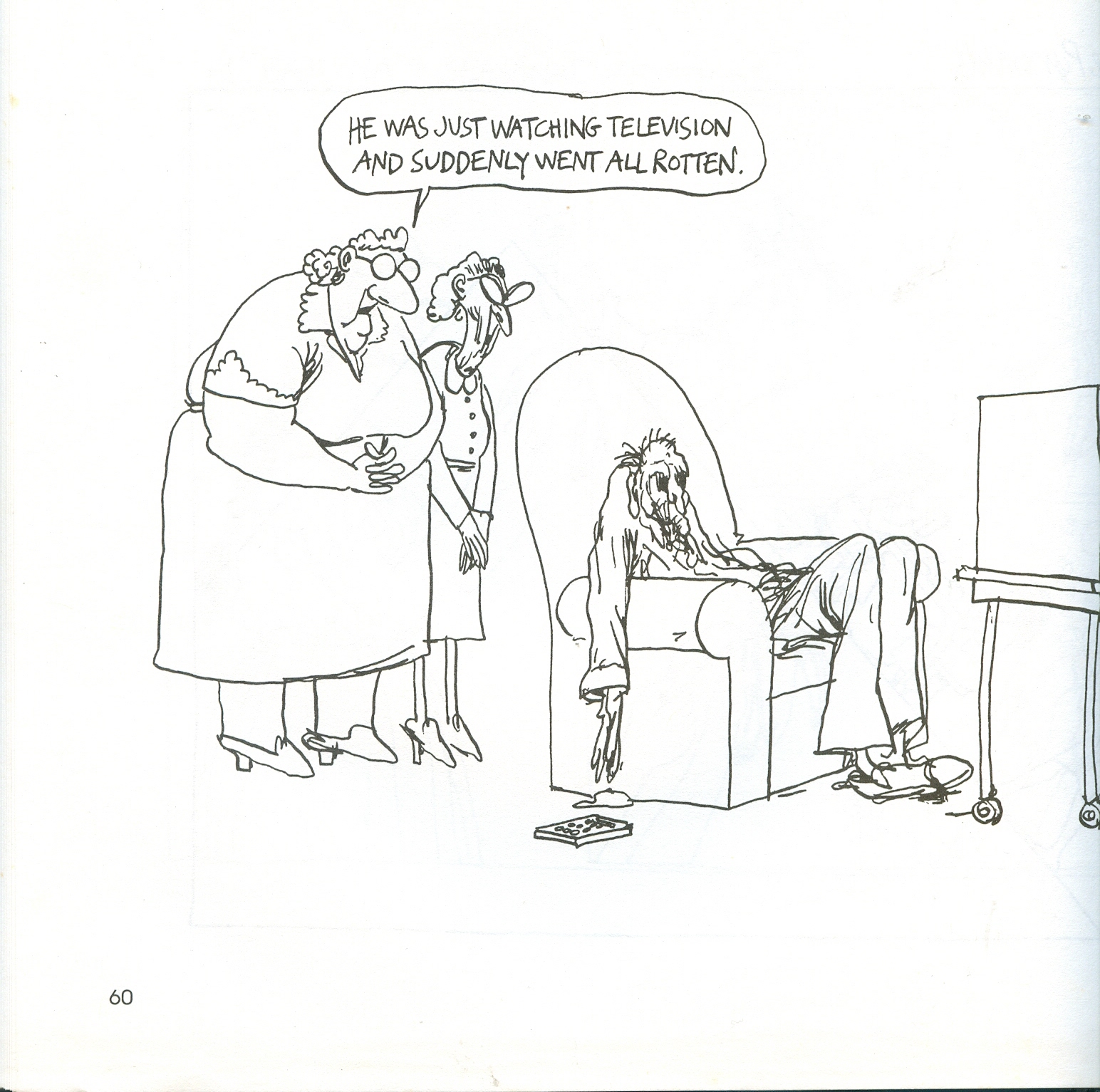

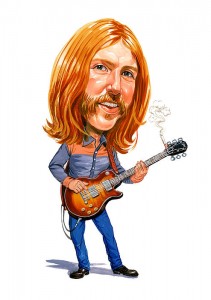

Caricature of Duane Allman courtesy of truefire.com. Artwork by: http://www.exaggerart.com/

1. The Allmans’ date at The Scene in Milwaukee was September 9, 1970. B bootleg recordings of the gig is available online: http://www.guitars101.com/forums/f90/allman-brothers-1970-09-04-milwaukee-wi-105755.html

I now realize, from the bootleg, that I missed half the set, including Dreams, but walking in as they launched into Elizabeth Reed was unforgettably worth the price of admission. This was a few weeks before their second gig at Fillmore East in New York, on September 23. Their acclaimed recordings at that venue would come in March and June of 1971. Duane Allman died in October, 1971, at age 24, on his Harley Davidson motorcycle, a death witnessed by two women friends driving behind him. Bassist Berry Oakley was driving behind the two women.( Freeman 109). Oakley would die almost exactly a year later — also at age 24, also in a motorcycle accident — on a Macon street about a thousand feet from where Allman died (141).

- Scott Freeman, Midnight Riders: The Story of the Allman Brothers Band Little Brown & Co. 1995

- Mark Kemp, Dixie Lullaby: A Story of Music, Race and New Beginnings in a New South, Free Press 2004

- Robert Penn Warren, Melville the Poet, from New and Selected Essays, Random House, 1989 p 229

- from a book in progress, From the Silt to the Soul: The New Literature and Culture Of Roots Music.

- Special thanks to Stuart Levitan.